.jpg.webp)

A kilij (from Turkish kılıç, literally "sword")[1] is a type of one-handed, single-edged and curved scimitar used by the Seljuk Empire, Timurid Empire, Mamluk Empire, Ottoman Empire, and other Turkic khanates of Eurasian steppes and Turkestan. These blades developed from earlier Turko-Mongol sabers that were in use in lands controlled or influenced by the Turkic peoples.

History

.JPG.webp)

Etymology

Most of Turkologists and linguists including Bican Ercilasun and Sevan Nişanyan think that it is derived from the Turkic root kıl- which means "to forge" or "to smith", with the diminutive suffix -ıç which creates kıl-ıç (roughly "ironwork", i.e. "sword"). Also one of the earliest mentions of the word was also recorded as kılıç (altun kurugsakımın kılıçın kesipen, an Old Turkic phrase from the Orkhon Inscriptions which was erected in 735 AD) in the age of Turkic Khaganate, instead of the other suggested Old Turkic reconstructed form of kırınç.[2] However, according to Turkish Language Association, the Turkish root verb kır- which means "to kill"[3] with the suffix -inç makes kır-ınç (instrument for killing) becomes kılınç, then kılıç, which is apparently not based on the earliest attested forms of the word.

The kilij became the symbol of power and kingdom. For example, Seljuk rulers carried the name Kilij Arslan (kılıç-arslan) means "sword-lion".

Origins

The Central Asian Turks and their offshoots began using curved cavalry swords beginning from the late Xiongnu period.[4] The earliest examples of curved, single edged Turkish swords can be found associated with the late Xiongnu and Kök-Turk empires.[5] These swords were made of pattern welded high carbon crucible steel, generally with long slightly curved blades with one sharp edge. A sharp back edge on the distal third of the blade known as yalman or yelman was introduced during this period.

Stewart%252C_Later_3rd_Marquess_of_Londonderry%252C_1812%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_National_Portrait_Gallery%252C_London.jpg.webp)

In the Early Middle Ages, the Turkic people of Central Asia came into contact with Middle Eastern civilizations through their shared Islamic faith. Turkic Ghilman slave-soldiers serving under the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates introduced kilij-type sabers to all of the other Middle Eastern cultures. Previously, Arabs and Persians used straight-bladed swords such as the earlier types of the Arab saif, takoba and kaskara.

During Islamizaton of the Turks, the kilij became more and more popular in the Islamic armies. When the Seljuk Empire invaded Persia and became the first Turkic Muslim political power in Western Asia, kilij became the dominant sword form. The Iranian (Persian) shamshir was created during the Turkic Seljuk Empire period of Iran/Persia.[6]

Evolution of the Ottoman kilij

The kilij as a specific type of sabre associated with the Ottoman Turks starts to appear historically from primarily the mid 15th century. One of the oldest known examples is attributed to Özbeg Khan, khaghan of the Golden Horde, from the early 14th century, and is currently on display in the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.[7] The oldest surviving examples sport a long blade curving slightly from the hilt and more strongly in the distal half. The width of the blade stays narrow (with a slight taper) up until the last 30% of its length, at which point it flares out and becomes wider. This distinctive flaring tip is called a yalman "false edge", and it greatly adds to the cutting power of the sword. Ottoman sabres of the next couple of centuries were often of the Saljuk variety, though the native kilij form was also found; Iranian blades (that did not have the yalman) were fitted with Ottoman hilts. These hilts normally had slightly longer quillons to the guard, which was usually of brass or silver, and sported a rounded termination to the grips, usually made of horn, unlike that seen on Iranian swords (Iranian swords usually had iron guards and the grip terminated in a hook-shape often with a metal pommel sheathing). The finest mechanical Damascus and wootz steel were often used in making of these swords. In the classical period of the Ottoman Empire, Bursa, Damascus and the Derbent regions became the most famous swordsmithing centers of the empire. Turkish blades became a major export item to Europe and Asia.

In the late 18th century, though shamshirs continued to be used, the kilij underwent an evolution: the blade was shortened, became much more acutely curved, and was wider with an even deeper yalman. In addition to the flared tip, these blades have a distinct "T-shaped" cross section to the back of the blade. This allowed greater blade stiffness without an increase in weight. Because of the shape of the tip of the blade and the nature of its curvature the kilij could be used to perform the thrust; in this it had an advantage over the shamshir whose extreme curvature did not allow the thrust.[8] Some of these shorter kilij are also referred to as pala, but there does not seem to be a clear-cut distinction in nomenclature.

After the Auspicious Incident, the Turkish army was modernized in the European fashion and kilijs were abandoned for western-type cavalry sabers and smallswords. This change, and the introduction of industrialized European steels to Ottoman market, created a great decline in traditional swordsmithing. Civilians in the provinces and county militia (zeybeks in Western Anatolia, bashi-bazouks in the Balkan provinces), continued to carry hand-made kilijs as a part of their traditional dress. In the late 19th century, Sultan Abdul Hamid II's palace guards, the Ertuğrul Brigade, which was composed of nomadic Turks of Anatolia, carried traditional kilijs as a romantic-nationalistic revival of the earlier Ottoman Turkoman cavalry raiders. This sentiment continued after dethronement of the sultan by the nationalist Young Turks. High-ranking officer non-regulation dress saber of early 20th century was a modern composite of traditional kilij, "mameluke" and European cavalry saber.

Adoption by Western armed forces

Sabres were known and used in eastern, and to a lesser extent central Europe from the time of the Magyar invasions, beginning in the 9th century (see the so-called Sabre of Charlemagne). Following the Ottoman invasion of Balkans, however, European armies were introduced to the kilij itself. The kilij first became popular with the Balkan nations and the Hungarian hussar cavalry after 15th century. Around 1670, the karabela (from Turkish word karabela: black bane) evolved, based on Janissary kilij sabres; it became the most popular sword-form in the Polish army. During 17th and 18th centuries, curved sabers that evolved from Turkish kilij were widespread throughout Europe.

The Ottomans' historical dominance of the region ensured the use of the sword by other nations, notably the Mamluks in Egypt. During the Napoleonic Wars, the French conquest of Egypt brought these swords to the attention of the Europeans. This type of sabre became very popular for light cavalry officers, in both France and Britain, and became a fashionable sword for senior officers to wear. In 1831 the "Mamaluke", as the sword was now called, became a regulation pattern for British general officers (the 1831 Pattern, still in use today). The American victory over the rebellious forces in the citadel of Tripoli in 1805 during the First Barbary War, led to the presentation of bejewelled examples of these swords to the senior officers of the US Marines. Officers of the US Marine Corps still use a mameluke pattern dress sword. Although some genuine Turkish kilij sabres were used by Westerners, most "mameluke sabres" were manufactured in Europe; their hilts were very similar in form to the Ottoman prototype, but their blades, even when an expanded yelman was incorporated, tended to be longer, narrower and less curved than those of the true kilij.

Terminology

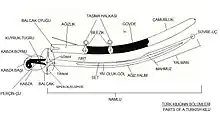

The Turkish language has numerous terminology describing swords, swordsmithing, parts and types of blades. Below is listed some of the terminology about names of the main parts of a kilij and scabbard in order of the term, literal translation of the Turkish word, and its equivalent in English terminology of swords.

| Term | Literal translation | Equivalent in English sword terminology – Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Taban | Base | Overall metal body of the sword that is composed of tang and blade |

| Namlu | Barrel | Blade |

| Kabza | Hilt | Hilt |

| Balçak | Guard | |

| Siperlik | Cover | Quillion |

| Kabza aşırması | Knuckle bow | |

| Kuyruk or tugru | Tail | Tang |

| Boyun | Neck (of the handle) | Grip |

| Kabza başı | Head of the handle | Pommel |

| Kabza tepeliği | Pommel cap | |

| Perçin or çij | Rivet | Rivet |

| Zıh | Frieze or border | Thin metal border that covers intersections of handle and tang |

| Ağız or yalım | Mouth | Edge |

| Sırt | Back | Back |

| Yiv, oluk or göl | Chamfer, groove or lake | Fuller |

| Set | Bank | Ridge |

| Yalman | Double edged end section of the blade | |

| Mahmuz | Spur | Martle |

| Namlu yüzü | Face of the blade | Flat of the blade |

| Süvre or uç | Point or tip | Point |

| Kın | Scabbard | Scabbard |

| Ağızlık | Mouthpiece | Locket |

| Çamurluk | Bumper | Chape |

| Balçak oyuğu | Guard cavity | Section of the locket where handguard fits in |

| Bilezik | Bangle | Ring mount |

| Taşıma halkası | Carrying ring | Suspension ring |

| Gövde | Body | Main part of the scabbard |

See also

- Dao (sword)

- Turko-Mongol sabers

- Mameluke sword: a derivative of the kilij

- Pulwar

- Saif

- Shamshir

- Tulwar

- Yatagan: another distinctive Turkish sword

- Sabre

- Szabla

- Scimitar

Notes

- ↑ Dictionary.com Unabridged - kilij entry

- ↑ kılıç. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ http://www.tdk.gov.tr/index.php?option=com_bts&arama=kelime&guid=TDK.GTS.59760a515c1491.98927628

- ↑ Çoruhlu, Yaşar "Erken Devir Türk Sanatı" p.74–75

- ↑ Ögel, Bahaaddin, "Türk Kılıcının Menşei ve Tekamülü Hakkında"

- ↑ Khorasani, Manouchehr, "Arms and Armour from Iran"

- ↑ "The Culture of the Golden Horde". The State Hermitage Museum. 2019.

- ↑ Stone and LaRocca, pp. 356–357.

References

- Stone, G. C. and LaRocca, D. J. (1999). A glossary of the construction, decoration and use of arms and armor in all countries and in all times. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-40726-8.

- ÖGEL, Bahaeddin, "Türk Kılıcının Menşe ve Tekamülü Hakkında", A.Ü. DTCF Dergisi, 6, 1948

- The Kilij and Shamshir. Turkish and Persian sabers Archived 2012-03-21 at the Wayback Machine