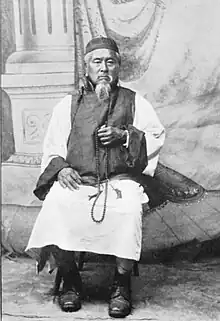

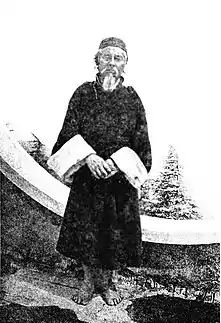

Kinthup, a Lepcha man from Sikkim, was an explorer in the area of Tibet in the 1880s. He is best known for his impressive devotion to duty in surveying a previously unknown area of Tibet.[1]

Laurence Waddell, who met Kinthup in 1892, described him as follows:[2]

[Kinthup] is a thick-set active man of medium height and middle age, with a look of dogged determination in his rugged, weather-beaten features ... His complexion is no darker brown than a swarthy Italian. His face is hairless save for one or two straggling bristles on his upper lip ... His deep-chested voice I have often heard calling clearly from a hill-top some miles away.

Biography

In the 1870s, the destination of the Tsangpo River (sometimes spelled "Sanpo") was unknown. Some hypothesized that it was the same river that flowed into the Bay of Bengal under the name of Brahmaputra (also known as "Dihang"). To solve this mystery, Henry John Harman of the Great Trigonometrical Survey sent a pundit explorer, Nem Singh (known as "G. M. N.") to follow the Tsangpo and determine its ultimate destination. G. M. N. was accompanied by his assistant, a Sikkimese lepcha named Kinthup. After surveying a good portion of the river, the pair returned to India.[1]

In 1880, a Chinese lama was employed to continue G. M. N.'s work, and Kinthup was again hired to accompany him.[1] In 1880 Kinthup was sent back with the task of testing the Brahmaputra theory by releasing 500 specially marked logs into the river at a prearranged time at which Captain Harman, posted men on the Dihang-Brahmaputra to watch for their arrival.[3] However, in May 1881 near Tongyuk Dzong, the Chinese lama sold Kinthup to a dzongpon to become his slave.[4] Kinthup's surveying equipment and notebooks were confiscated and he remained a slave until March 1882, when he finally managed to escape.[1]

Resuming his survey of the river, he followed the gorge southward until he was captured by servants of his former master and again sold into slavery to the head abbot of a monastery. He was well-treated by his new master, and was granted several leaves of absence under the guise of making religious pilgrimages. This gave him the opportunity to prepare 500 logs and send a letter to Harman from Lhasa announcing his new intended schedule. He also made several long treks recording the extent of the Tsangpo and surrounding region, and determined that the two rivers were indeed one and the same. After fifteen months of servitude at the monastery, he was granted his freedom by the abbot, and was finally able to launch the logs. However, Harman had died in the interim and Kinthup's letter went unread, so nobody checked for the appearance of the logs.[3][1]

Kinthup returned to India in November 1884, four years after he had left.[1] It was not until two years later that his account was even recorded, and even then his extraordinary accounts were doubted by some geographers.[1] "His accomplishment was not acknowledged until 1913, when F. M. Bailey and Henry Morshead validated his claims."[5]

Captain Hugh Trenchard said, "his account has been confirmed in the most remarkable manner, and we are now able to establish Kinthup's claim to honorable record in the annals of the Survey of India, which he served with such zeal and devotion to duty."[1] It was only some 30 years later that the Bailey–Morshead exploration of Tsangpo Gorge conclusively confirmed his discovery.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Burrard, S. G. (1915). "The Identity of the Sanpo and Dihang Rivers". Bulletin of the American Geographical Society. American Geographical Society. 47 (4): 259–264. doi:10.2307/201464. JSTOR 201464.

The report of Capt. O.H.B. Trenchard R.E. ... says: ... 'his account has been confirmed in the most remarkable manner, and we are now able to establish Kinthup's claim to honorable record in the annals of the Survey of India, which he served with such zeal and devotion to duty'.

- ↑ Waddell, L. A. (1899). Among the Himalayas. Archibald Constable & Co. p. 67.

- 1 2 Allen, Charles (1982). A Mountain in Tibet: The Search for Mount Kailas and the Sources of the Great Rivers of Asia. London: Abacus.

- ↑ Baker, Ian (2006-05-02). The Heart of the World: A Journey to Tibet's Lost Paradise. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-11780-4.

- ↑ Wade, Davis (2012). Into the Silence : The Great War, Mallory, and the Conquest of Everest. New York: Vintage Books. p. 50. ISBN 9780375708152. OCLC 773021726.

His accomplishment was not acknowledged until 1913, when F. M. Bailey and Henry Morshead validated his claims...