Marcus Klingberg | |

|---|---|

מרקוס קלינגברג | |

| |

| Born | 7 October 1918 |

| Died | 30 November 2015 (aged 97) |

| Nationality | Poland (1918–1948) Israel (1948–2015) |

| Occupation(s) | Epidemiologist, spy |

| Spouse | Wanda Jasinska |

| Children | 1 (daughter) |

| Relatives | Ian Brossat (grandson) |

| Awards | Order of the Red Banner of Labour |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Captain (Red Army) Lieutenant colonel (IDF) |

Avraham Marek Klingberg (7 October 1918 – 30 November 2015), known as Marcus Klingberg (Hebrew: מרקוס קלינגברג), was a Polish-born, Israeli epidemiologist and the highest ranking Soviet spy ever uncovered in Israel.

Klingberg's espionage is reported to be regarded by Israeli intelligence services as the most damaging ever to the country's national security interests.[1][2]

Early life

Klingberg was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1918, to a Hasidic Jewish family of rabbinical lineage. In his youth, he lived for a time with his grandfather, Rabbi Moshe Chaim Klingberg. His parents sent him to a cheder, a religious primary school. As a teenager, he abandoned religion and attended a secular high school.[3]

In 1935, Klingberg began studying medicine at the University of Warsaw. In 1939, with the German invasion of Poland and the outbreak of World War II, Klingberg was urged by his father to flee to the Soviet Union. There, he completed his medical studies in Minsk in 1941.[4][5]

His parents and younger brother, who remained in Poland, were murdered in 1942 in the Treblinka extermination camp.[4]

World War II

On 22 June 1941, the first day of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, he volunteered for the Red Army, and served as a medical officer on the front lines until October 1941, when he was wounded in the leg by shrapnel. He recovered, and was then assigned to Perm in the Urals as leader of an anti-epidemic unit.[6][3]

In 1943, he undertook postgraduate studies in epidemiology in Moscow at the Central Institute for Advanced Medical Training under Lev Gromashevsky, the "so called master of Soviet epidemiology".[5][6] That same year, he was part of a team that stopped an epidemic in the Urals. He also made a contribution into research toward typhoid fever. Toward the end of December 1943, the first parts of Byelorussia were retaken by the Red Army and Klingberg became Chief Epidemiologist of the Byelorussian Republic.[7]

At the end of the war, Klingberg was discharged from the Red Army with the rank of captain, and returned to Poland. In Warsaw he served as Acting Chief Epidemiologist at the Polish Ministry of Health.[7][3]

Scientific career in Israel

In November 1948, Klingberg immigrated to the newly formed state of Israel, which was in the closing stages of its War of Independence, with his wife and daughter. Israeli journalist Yossi Melman reported Shin Bet claims that the immigration was prompted by Soviet intelligence, but Klingberg has strongly denied this, indicating that his desire to move to Israel was motivated by the loss of his family in Poland.[3][8]

Although Klingberg said that he was not a Zionist, he claimed that he moved to Israel because he was Jewish and because the Soviet Union supported Israel at that time.[3] He was drafted into the Israel Defense Forces, and served in the Medical Corps. In March 1950, he advanced to the rank of lieutenant colonel (Sgan Aluf). He served as Head of the Department of Preventive Medicine and afterward he founded and chaired the Central Research Laboratories for Military Medicine.

In 1957, he joined the top-secret Israel Institute for Biological Research in Ness Ziona (south of Tel Aviv), where he served as Deputy Scientific Director (until 1972). He also served as Head of the Department of Epidemiology until 1978. In 1969, Klingberg joined the Sackler Faculty of Medicine of Tel Aviv University, and was Professor of Epidemiology and Head of the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine from 1978 to 1983.

Klingberg's academic career and research papers earned him an international reputation in his field, and he was invited to take part in conferences by the World Health Organization.[3] He was president of the European Teratology Society (1980–1982); and a co-founder and chairman (1979–1981) of the International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Monitoring Systems (ICBDMS). He also served as president of the International Steering Committee for the Seveso Accident (Italy) from 1976 to 1984. In 1981, he co-founded the International Federation of Teratology Societies and in 1982 at the congress of the International Epidemiological Association that was held in Edinburgh, Scotland, he was elected to its council.

Klingberg spent his sabbaticals at the Henry Phipps Institute, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, United States, from 1962 to 1964; at the National Institute for Public Health, Oslo, Norway (1972); at the Department of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK (1973); at the Department of Social and Community Medicine, University of Oxford and became a Visiting Fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford (1978).

At the time of his arrest, Klingberg was series editor of Contributions to Epidemiology and Biostatistics and co-chief editor of Public Health Reviews.

Espionage activities in Israel

According to Klingberg's indictment, which was based on his confession, he began spying in 1957. From then to 1976, Klingberg passed information on Israel's chemical and biological weapons research.[3][9] Israel's foreign and domestic intelligence agencies, Mossad and Shin Bet, began to suspect Klingberg of espionage in the 1960s, but shadowing brought no results. While at the Institute for Biological Research, he was twice summoned by the authorities due to suspicions of him being a foreign agent. Klingberg refuted these claims, and in 1965 he passed a polygraph test, reportedly due to the fact that his interrogators simply asked the wrong questions, as they suspected he was spying for Polish rather than Soviet intelligence.[10][11]

In the 1950s, Klingberg was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour in recognition of his service to the Soviet Union.

Capture, trial and detention

In 1982, a Soviet Jew who immigrated to Israel after being granted an exit visa approached the Israeli security services and told them that the KGB had recruited him as a spy. Shin Bet subsequently ran him as a double agent, and through him, obtained strong circumstantial evidence that Klingberg was a Soviet spy. Despite this, the Shin Bet had not obtained solid evidence that would be admissible in court, and decided to elicit a confession out of him. In January 1983, Shin Bet officers informed Klingberg they wanted to send him to Singapore where a chemical plant allegedly blew up. After leaving home with his suitcase, he was taken not to the airport but to an apartment in some undisclosed location where he was interrogated harshly and put under psychological pressure to confess. After ten days, Klingberg admitted to being a Soviet mole and signed a confession. He claimed that he had provided information to the Soviet Union only for ideological reasons.

Klingberg was tried in secret and sentenced to 20 years in prison. For the first 10 years of his 20-year sentence he was held in solitary confinement, in a high security prison in Ashkelon under the false name of Abraham Grinberg and the fabricated profession of a publisher.[13] After he was removed from solitary confinement, his cellmate was Shimon Levinson, another Israeli who spied for the Soviet Union.

Klingberg claimed that he spied out of ideological reasons, and that he was never paid. However, he told his interrogators that he had not completed his medical studies and lacked a diploma, and that the KGB had blackmailed him by threatening to expose this.[14]

In an interview after his release, Klingberg maintained that he had spied out of ideological reasons, but had lied to his interrogators and said he had been blackmailed so he would receive a lighter sentence.[3][9] In an interview in 2014 he said that he also felt he owed the Russians a debt for saving the world from the Nazis. He said he had always been a communist, and had recruited his wife Wanda and two friends.[15]

In 1988-89, East Germany and the Soviet Union began negotiations with Israel, where a proposal was tentatively agreed to release Klingberg, along with Shabtai Kalmanovich, in exchange for the Soviet Union providing information on the location of Ron Arad, an Israeli Air Force navigator believed to be held in Lebanon. With the downfall of communism in Eastern Europe, the deal fell apart.[16][17]

In 1997, Amnesty International appealed to the Israeli government to release Klingberg on medical grounds.[18] Because of his failing health (he had several strokes), he was released under house arrest in October 1998. Former Shin Bet director, Yaakov Peri, acted as a character witness.[10]

At his expense, a camera was installed in his apartment, which was hooked up to the offices of MALMAB (military security) at the Kirya, Tel Aviv. His telephone was tapped, with his knowledge. Guards from MALMAB were assigned to him, and Klingberg had to pay their salaries. Klingberg also signed a commitment not to speak about his work. In 1999, a court ordered him to cease speaking Yiddish and Russian at home as the guards could not understand those languages and therefore could not monitor his conversations. In order to pay the guards and for the camera, Klingberg took loans, and eventually had to sell his apartment to repay them.[3][19]

Release and later life

On 18 January 2003, Klingberg was released from house arrest. He immediately left for Paris to live with his daughter Sylvia and grandson Ian.

Klingberg lived in a one-room apartment in Paris, but did not take French citizenship. He frequently lectured on medicine at universities. He helped establish the Ludwik Fleck Center of the Collegium Helveticum - a university center in Zürich, and delivered the opening lecture. He received an officer's pension from the Israeli government, which in France amounted to around € 2,000 a month. Klingberg continued to have medical problems after his release, and was frequently hospitalized.[3] He continued to take an interest in events in Israel, and read Hebrew newspapers.

Klingberg published his memoirs, HaMeragel Ha'akharon ("The Last Spy"), written together with his lawyer, Michael Sfard, in 2007.[20]

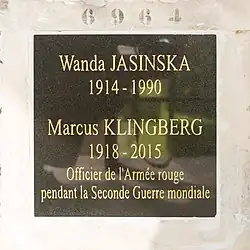

Klingberg died in Paris on 30 November 2015, aged 97.[21] He was cremated, and his ashes were interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Personal life and family

While living in post-war Poland, Klingberg met Adjia Eisman, who went by the name Wanda Jasinska. A microbiologist by profession, she was a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto. She assumed a Christian identity in order to survive, but her parents and siblings were murdered.[22]

Klingberg and Jasinka married and in 1946 they decided to emigrate to the West. They moved to Sweden shortly afterward, where their daughter Sylvia was born in 1947.[9][11] In September 1990, Jasinska died. In accordance with her wishes, she was cremated and her ashes interred at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.[3]

Klingberg's daughter, Sylvia, became a left-wing activist in Israel and member of the socialist anti-Zionist movement Matzpen. In 1975, she married Ehud Adiv, an Israeli political activist serving a prison sentence on charges of spying for Syria, in a ceremony held in Ayalon Prison. They divorced after three years. Sylvia later emigrated to France, where she was active in the far-left and married French philosopher Alain Brossat. Their son, Ian Brossat (born 1980), has been a member of the Paris City Council since 2008, representing the French Communist Party.[23] Sylvia died of cancer in October 2019.[22]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Rimmington 2000, p. 41.

- ↑ Morabia 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Melman & Klingberg 2006.

- 1 2 Grimes 2015.

- 1 2 Stafford 2015.

- 1 2 Rimmington 2018, p. 161.

- 1 2 Morabia 2006, p. 116.

- ↑ Klingberg 2010, p. 420.

- 1 2 3 Ynet 2008.

- 1 2 Jerusalem Post 2015.

- 1 2 Melman 2007.

- ↑ Klingberg 2007.

- ↑ Brossat & Klingberg 2016 Preface

- ↑ Tibon 2008.

- ↑ Pringle 2014.

- ↑ Kahana 2006, p. 152.

- ↑ Ginor & Remez 2007, p. 225.

- ↑ Amnesty International 1997.

- ↑ Jerusalem Post 1999.

- ↑ Klingberg & Sfard 2007.

- ↑ Issacharoff 2015.

- 1 2 Aderet 2019.

- ↑ Gruet 2009.

Sources

Primary

- Klingberg, Marcus; Sfard, Michael (2007). המרגל האחרון [The Last Spy] (in Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Ma'ariv Library. p. 423.

- Klingberg, Marcus (24 August 2007). "קלינברג מציג: הדברים שלא סיפרתי לשב"כ" [Klingberg: The things I didn't tell Shin Bet]. www.makorrishon.co.il (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on 26 August 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- Klingberg, Marcus (1 October 2010). "An epidemiologist's journey from typhus to thalidomide, and from the Soviet Union to Seveso". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 103 (10): 418–423. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k037. PMC 2951169.

- Melman, Yossi; Klingberg, Marcus (31 May 2006). "I Spy". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 30 May 2008.

- Morabia, Alfredo (January 2006). ""East Side Story": On Being an Epidemiologist in the Former USSR: An Interview With Marcus Klingberg". Epidemiology. 17 (1): 115–119. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000184473.33772.ed.

Secondary

- Aderet, Ofer (28 October 2019). "This Revolutionary Israeli Woman Married a Spy – Only to Learn That Her Father Is One, Too". Haaretz. ProQuest 2309235663.

- Amnesty International (6 June 1997). "Medical Letter Writing Action: Avraham Marcus KLINGBERG, Israel/Occupied Territories". Archived from the original on 25 April 2005.

- Brossat, Alain; Klingberg, Sylvia (2016). Revolutionary Yiddishland: a history of Jewish radicalism. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-78478-609-0.

- Ginor, Isabella; Remez, Gideon (2007). Foxbats over Dimona: the Soviets' nuclear gamble in the Six-Day War. New Haven (Conn.): Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12317-3.

- Grimes, William (3 December 2015). "Marcus Klingberg, Highest-Ranking Soviet Spy Caught in Israel, Dies at 97". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- Gruet, Magali (24 February 2009). "Ces jeunes politiques qui jouent déjà un rôle capital à Paris" [These young politicians are already playing a crucial part in Paris]. www.20minutes.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 27 October 2022.

- Issacharoff, Avi (30 November 2015). "Notorious spy Marcus Klingberg dies at 97". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 26 January 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- Kahana, Ephraim (2006). "Klingberg, Avraham Marcus". Historical dictionary of Israeli Intelligence. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-8108-5581-6.

- "Marcus Klingberg". Ynetnews. 4 May 2008. Archived from the original on 27 November 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- "Marcus Klingberg, the Israeli who spied for the Soviet Union, dies at 97". Jerusalem Post. 12 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- Melman, Yossi (21 September 2007). "'The Best Keeper of Secrets in the World'". Haaretz.

- "Oy vey? No way. Ex-spy Klingberg barred from speaking Yiddish". Jersalem Post. Associated Press. 22 January 1999. ProQuest 319236095.

- Pringle, Peter (27 April 2014). "Marcus Klingberg: the spy who knew too much". The Observer. Archived from the original on 8 October 2023.

- Rimmington, Anthony (September 2000). "Invisible weapons of mass destruction: The Soviet Union's BW programme and its implications for contemporary arms control". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 13 (3): 1–46. doi:10.1080/13518040008430448.

- Rimmington, Anthony (15 October 2018). Stalin's Secret Weapon: The Origins of Soviet Biological Warfare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-005023-8.

- Shpiro, Shlomo (December 2011). "KGB Human Intelligence Operations in Israel 1948–73". Intelligence and National Security. 26 (6): 864–885. doi:10.1080/02684527.2011.619801.

- Shpiro, Shlomo (4 July 2015). "Soviet Espionage in Israel, 1973–1991". Intelligence and National Security. 30 (4): 486–507. doi:10.1080/02684527.2014.969588.

- Stafford, Ned (22 December 2015). "Obituary: Marcus Klingberg". British Medical Journal. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6965.

- Tibon, Amir (15 April 2008). "Double agent enabled Israel's capture of top-ranked Soviet spy Klingberg - Haaretz - Israel News". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 10 June 2017.