| Kogia pusilla Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Top (left) and underside (right) views of the skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Kogiidae |

| Genus: | Kogia |

| Species: | †K. pusilla |

| Binomial name | |

| †Kogia pusilla Pilleri, 1987 | |

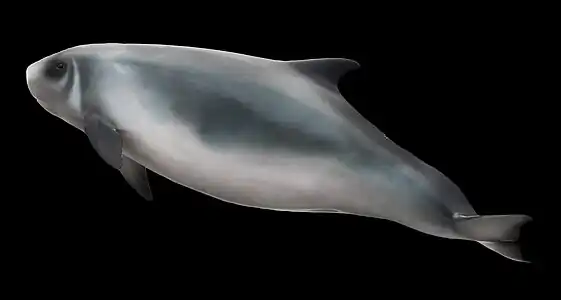

Kogia pusilla is an extinct species of sperm whale from the Middle Pliocene of Italy related to the modern day dwarf sperm whale (K. sima) and pygmy sperm whale (K. breviceps). It is known from a single skull discovered in 1877, and was considered a species of beaked whale until 1997. The skull shares many characteristics with other sperm whales, and is comparable in size to that of the dwarf sperm whale. Like the modern Kogia, it probably hunted squid in the twilight zone, and frequented continental slopes. The environment it inhabited was likely a calm, nearshore area with a combination sandy and hard-rock seafloor. K. pusilla likely died out due to the ice ages at the end of the Pliocene.

Taxonomy

| Kogiidae | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| K. pusilla within Kogiidae[1] |

The holotype specimen, IGF1540V, comprises an incomplete skull lacking teeth, mandibles, and the right and bottom side of the braincase. It was found in La Rocca locality near the city of Volterra in Tuscany, Italy, an area that is dated to the Middle Pliocene between 3 and 2.6 million years ago (mya). Teeth and periotic bones of the inner ear were also found in the area, possibly belonging to K. pusilla.[2][3]

The skull was first donated to the Museo di Paleontologia of the University of Florence in 1877 by Italian paleontologist Roberto Lawley. In 1893, paleontologist Giovanni Capellini thought it was a beaked whale; on first look, he thought it represented the genus Choneziphius, but then he concluded it represented the now-dubious genus Placoziphius based on similarities with the snouts.[4] In 1987, it was described as Hyperoodon pusillus as a species of bottlenose whale–which is also a beaked whale–by Georg Pilleri.[5] In 1997, it was finally described as K. pusilla by geologist Giovanni Bianucci. The species name pusilla is Latin for "small".[2][6][7]

K. pusilla is the third fossil kogiid whale described, after Praekogia from 1973 and Scaphokogia from 1988, and the third member of the genus Kogia, with the modern day dwarf sperm whale (K. sima) and pygmy sperm whale (K. breviceps).[2] The other two kogiids are Thalassocetus and Nanokogia.[1]

The dwarf and pygmy sperm whales are more derived than K. pusilla.[2] The discovery of K. pusilla pushed up the divergence point between the dwarf and pygmy sperm whales from the previous estimate of around 9.3 mya to after Early Pliocene 5.3 mya.[1]

Description

K. pusilla is differentiated from the dwarf and pygmy sperm whales by its more elongated snout, smaller lacrimal bone, less pronounced cheekbones, less elevation of the back top side of the skull, and more asymmetry between the left and right sides of the skull. It is smaller than the pygmy sperm whale and has a narrower sagittal crest along the mid-line of the skull. The blowhole is displaced even farther to the left than in modern-day Kogia and the sagittal crest more to the right. However, the skull size is comparable to that of the dwarf sperm whale. The braincase of K. pusilla has a basin formed by the right premaxilla, which, in modern Kogia, houses the spermaceti organ. The organ is unique to sperm whales and aids in echolocation by focusing sound. Due to the less-pronounced cheekbones, the anterior cranial fossa–depressions on the skull–are smaller than in modern Kogia. The lacrimal bone is hooked-shape like in Physeteridae in contrast to the triangular lacrimal bone of Kogiidae. Like other kogiids, it does not have nasal bones.[2] Thinking it was a beaked whale and using the holotype of Placoziphius for scale, Capellini estimated the length at 1.25 meters (4.1 ft).[4]

Paleoecology

K. pusilla, like the other Kogia, had a blunt snout, likely an adaptation for suction feeding. It, like the modern Kogia, probably hunted squid in the sunlight and twilight zones between 100 and 700 meters (330 and 2,300 ft). Considering the squid-eating fossil pilot whale Globicephala etruriae was discovered in the same area and occupied the same niche, squid were probably more abundant in the Mediterranean during the Pliocene than present-day.[1][2]

Paleobiology

The Rocca locality in Volterra is representative of a neritic-to-littoral zone along a continental slope. The dwarf and pygmy sperm whales also inhabit the continental slope.[2] The area has yielded the extinct dolphins Etruridelphis and Hemisyntrachelus, G. etruriae, the baleen whale Balaena paronai, the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), the Mesoplodon beaked whales M. lawleyi and M. danconae, and the manatee Metaxytherium subapenninum.[8] The area has an unusually large and one of the most diverse decapod crustacean assemblages known from the Pliocene; this implies a sandy-muddy and at places hard-rock seafloor with calm, well-oxygenated, nearshore water, which are conducive for decapod life. Further, areas could have been covered with seagrass, similar to the modern day Mediterranean neptune grass (Posidonia oceanica). Some invertebrates, including a possible squid cuttlebone, were preserved.[9] K. pusilla likely died out along with several fish and mollusk species in an extinction event in the Mediterranean in the Late Pliocene with the onset of the ice ages.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Valez-Juarbe, J.; Wood, A. R.; De Gracia, C.; Handy, A. J. W. (2015). "Evolutionary patterns among living and extinct kogiid sperm whales: evidence from the Neogene of Central America". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0123909. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123909. PMC 4414568. PMID 25923213.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bianucci, Giovanni; Landini, Walter (1999). "Kogia pusilla from the Middle Pliocene of Tuscany (Italy) and a phylogenetic analysis of the family Kogiidae (Odontoceti, Cetacea)". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 105 (3). doi:10.13130/2039-4942/5385. ISSN 2039-4942.

- ↑ Bianucci, G.; Sarti, G.; Catanzariti, R.; Santini, U. (1998). "Middle Pliocene cetaceans from Monte Voltraio (Tuscany, Italy). Biostratigraphical, paleoecological and paleoclimatic observations". Revista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 104 (1): 124–126. ISSN 0035-6883.

- 1 2 Capellini, G. (1893). "Nuovi resti di Zifioidi in Calabria e in Toscana" [New Ziphoidea remains in Calabria and Tuscany] (PDF). Rendiconti (in Italian). 2: 283–288.

- ↑ Pilleri, G. (1987). The Cetacea of the Italian Pliocene: with a descriptive catalogue of the specimens in the Florence Museum of Paleontology. Brain Anatomy Institute. OCLC 19115575.

- ↑ Bianucci, G. (1997). "The Odontoceti (Mammalia: Cetacea) from Italian Pliocene. The Ziphiidae". Palaeontographia Italica. 84: 1–7.

- ↑ Cioppi, E. (2014). "I cetacei fossili a Firenze, una storia lunga più di 250 anni" [The fossil cetaceans of Florence, a history of more than 250 years] (PDF). Museologia Scientifica Memorie (in Italian): 81–89.

- ↑ "Volterra (Pliocene of Italy)". Fossilworks. Retrieved 13 August 2018 from the Paleobiology Database.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Garassino, A.; Pasini, G.; de Angeli, A.; Charbonnier, S.; Famiani, F.; Baldanza, A.; Bizzari, R. (2012). "The decapod community from the Early Pliocene (Zanclean) of "La Serra" quarry (San Miniato, Pisa, Toscana, central Italy): sedimentology, systematics, and palaeoenvironmental implications" (PDF). Annales de Paléontologie. 98: 1–62. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2012.02.001. ISSN 0753-3969.