| Kore of Lyons | |

|---|---|

| |

| Material | Pentelic marble |

| Size | Bust : 64 cm high ; 36 cm wide; 24 cm deep Arm fragment: 65 cm |

| Created | Ancient Greece |

| Period/culture | Archaic Period, c. 540s BC |

| Discovered | Unknown. First mentioned in 1719. Unknown |

| Present location | • Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon, France • Acropolis Museum, Athens , Greece. |

| Identification | Lyon Inv. H1993 & Athens Acr. 269 |

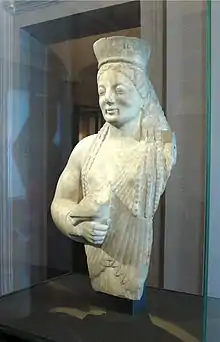

The Kore of Lyons (French: Coré de Lyon) is a Greek statue of Pentelic marble depicting a bust of a young girl of the kore type, conserved at the musée des beaux-arts de Lyon, France. Deriving from the Athenian Acropolis, it is generally dated to the 540s BC. Considered the centrepiece of the museum's antiquities department,[1] the statue was acquired between 1808 and 1810.

The sculpture is fragmentary: the bust is conserved in the musée des beaux-arts de Lyon under the inventory number H 1993, while the lower portion and some fragments of the left arm are conserved in the Acropolis Museum in Athens, under inventory number Acr. 269. After a series of comparisons, the connection between the fragments was definitively established in 1935 by Humfry Payne.[2]

It was one of the numerous Korai of the Acropolis of Athens discovered during the construction of the old Acropolis Museum in the Perserschutt, a layer of destruction from the Persian Wars, containing material from the 570s BC down to the end of the sixth century BC. It represents the first example of the Ionian influence which entered Attic sculpture in the second half of the century and first use of Ionian costume in Attica. The Kore of Lyons is of the generation after the oldest Kore discovered on the Acropolis, Acropolis 593, and represents the beginning of the new phase of Attic sculpture beginning in the third quarter of the sixth century.

The Kore of Lyons has been suggested to have had an architectural function as a caryatid[3] or a votive function.[4]

Description

Portion in Lyon

.jpg.webp)

Characteristic of its type, the Kore of Lyons is a pentelic marble sculpture measuring 64 cm in height, 36 cm wide and 24 cm deep.[4] It depicts the bust of a majestic young woman, who holds an offering against her breast, a bird, identified by some as a dove. The sculpture was painted.[4] Influenced by the art of the Ionian coast, it is dressed in a chiton and himation. She wears a polos atop her head and earrings.

Identification difficulties

Mountfaucon and Grosson described it as an Egyptian statue at the beginning of the 18th century. This theory was rapidly dismissed, but its identification remained debated. A certain Egyptomania caused some researchers to see a "Gallic Isis," while others perceived an "Archaic Venus."[4] It had to wait until the beginning of the 20th century and a greater understanding of Greek art to refine the analysis; in the meantime identifications included an Ionian Aphrodite, an Athena or the Sidonian Astarte of Paphos, assimilated to Aphrodite.[4] In 1923 Henri Lechat published an inventory of the collection of casts of the Lumière University Lyon 2 where he described the statue as "the upper part of a statue of Aphrodite ... clad in the Ionian fashion... a kore, specifically a goddess by the polos on her head and identified as Aphrodite by the dove in her right hand."[4] But Pane refuted this hypothesis, arguing that the polos is not strictly a divine attribute and restated the hypotheses that it was a caryatid on account of a hole present at the top of the head for the attachment of a tenon, or a votive statue on account of its small size.[4]

Ionian or Attic?

Costume

The statue has the compact and robust structure which is typical of this period in Attica and goes back to the Berlin Goddess (Pergamon Museum SK 1800, first quarter of the sixth century). Ionian characteristics are clear, notably the costume, composed of a chiton with long sleeves and a himation pinned diagonally over one shoulder. In sculpture and Attic black figure pottery, contemporary women wear the sleeveless Doric peplos over a light chiton and the himation, when it is present at all, is pinned at both shoulders. The sole archaic Attic representation which wears the chiton without the peplos over it is the Berlin Goddess, but she wears the himation in the traditional symmetric manner. In Ionia on the other hand, the diagonal himation is very well attested from the second quarter of the 6th century BC, e.g. on the statues dedicated by Cheramyes; not only is the origin of this garment Ionian, but also the treatment of the drapery, which is found in the representations of the columnae caelatae of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (generally dated to 560 BC). Another stylistic element of the Kore of Lyons is the curve of the himation above the buttocks which is not subsequently imitated by Attic sculptors, but is fairly frequent in contemporary vase painting and marble sculpture of the Greek East.[5]

Stylistic syncretism

These different influences (Ionian and Athenian) mean that even today the identification of the statue is not possible.[4] However, according to some stylistic and technical criteria, the statue belongs to Attic sculpture of the Archaic period (thick hair, receding chin, almond shaped eyes) while undergoing Ionian influence (chiselled rounding, softened facial lines) which increased at the end of the sixth century.[4] It must however be noted that the Ionian elements are in the majority, notably the typically Ionian long-sleeved chiton, the Ionian himation and the polos decorated with lotus flowers and palmettes. However the material, Pentalic marble from north of Athens, and the rigorous composition settle the question in favour of an Attic origin.[4]

The Kore of Lyons is evidence of a stylistic syncretism. Its hesitant proportions, the stiff awkward robustness and the non-realistic details allow the statue to be dated to the "mature" Archaic period, around 550-540 BC.[4]

Function

The question of the architectural function of the Kore of Lyons was solved by Brunilde Sismondo Ridgway in 1986; the upper part of the polos has some characteristics typical of caryatids, which Payne did not observe directly, but only through casts sent to Athens. The sculpture has a nick on the upper part for a tenon,[4] supporting the theory of an architectural role. Another element supporting this conclusion is the reversal of the diagonal himation (going over the left rather than the more usual right shoulder) which is typical of mirrored pairs rather than isolated works. In addition the origin of the Ionian influence detected in the style of the work matches the near eastern origin of the caryatid as an architectural feature. On the other hand, the kore is very small and would only fit as the caryatid of a small naiskos or a secondary entrance and even then it would have to have been placed on top of a podium.[3] A votive function cannot be excluded therefore.[4]

History

First mention and acquisition by le musée de Lyon

How the sculpture came from Greece to the south of France is unknown. It is possible that it was brought back by a seventeenth century aristocrat on the Grand Tour,[6] the voyage taken by young gentlemen of the upper classes of European society in order to complete their education, then based on the study of Greek and Latin. Before the connection of the fragments from the Acropolis with the torso in the musée de Lyon it was called the Aphrodite of Marseille and is mentioned for the first time in 1719 by Montfaucon in the second volume of his work, L'Antiquité expliquée, where he says that it was kept in "cabinet of Monsieur [Laurent] Gravier in Marseille"[4][7] and described it as belonging to Egyptian style, with an owl in the right hand;[7] there followed a series of publications of unverified data, which claimed the city of Marseille as the place of discovery, a claim which seemed plausible because it was the site of Massalia, an ancient colony of the Ionian city of Phocaea, founded in the 600s BC. Among various undocumented owners of the kore, it seems, according to Henri Lechat, to have been part of the collection Tempier of Nîmes, sold by a Lyonese antiquities dealer named Mercier in December 1810 for the nascent local museum. Lechat declared it to be "Greek, from Asia Minor."[7] According to other sources, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon acquired the statue from the collection of Monsieur Pinochi of Nîmes.[4] From this period, the statue was incomplete, notably lacking its left arm and its legs. The kore is present in the catalogue of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon of 1816.[8] The polos on the head and the dove were considered sufficient evidence to identify the statue as a representation of Aphrodite and the presence of the diagonal himation led to the conclusion that the statue was of Ionian origin.

Fragments reunited

Much later, research by Humfry Payne of the British School at Athens led to the rediscovery of the lower part of a statue which he thought to correspond to the "Aphrodite with the dove" (the name by which the statue was then known).[4] A cast of the kore created at the request of Payne confirmed this hypothesis. He was even able to identify fragments of hair and most importantly of the left arm in the uninventoried fragments of the Acropolis Museum.[4] The various fragments were reunited at the end of the 1930s to reconstitute the statue, which was thereby definitively identified as one of the Korai of the Acropolis of Athens.[4]

De-restoration

The main fragment in Lyon consisting of the upper part of the kore was supplemented by casts of the fragments in the museum at Athens until 1994. These elements were removed according to "a museological principle that desired, for the sake of archaeological and scientific truth, only to display the true material of what was possessed, without use of representational devices, such as completing the sculpture with other materials, plaster in this case, as if this plaster was a precise substitute for truth"[7] as Professor Jean-Claude Mossière, associate member for the study of ancient and contemporary Greece at the French School at Athens put it. Unlike the Musée de Lyon, the Acropolis Museum has chosen to continue to present the fragments it possesses with a plaster cast of the upper portion.[7]

References

- ↑ "Koré". Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ Humfry Payne (1935). The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (ed.). "The "Aphrodite" of Lyons". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 55 part 2: 228. doi:10.2307/627371.

- 1 2 Marszal 1988, passim

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Morgane Ivanoff, La 'korè' de Lyon, Université Lumière Lyon 2, musée des moulages, Lettres et Arts 2008/2009

- ↑ Payne 1936, pp. 109–110

- ↑ "Kore of Lyons". University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "La Coré de Lyon". jcmo.wordpress.com. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ François, Artaud (1816). Cabinet des antiques du musée de Lyon (in French). Lyon: impr. de Pelzin.

Bibliography

- Payne, Humfry (1936). Archaic marble sculpture from the Acropolis. Manchester: Cresset Press. (with Gerard Mackworth Young).

- Michon, Étienne (1935). "L'Aphrodite du Musée de Lyon complétée par un fragment de coré du Musée de l'Acropole d'Athènes". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 79 (3): 367–378..

- Marszal, John R. (1988). "An Architectural Function for the Lyons Kore". Hesperia. 57 (2): 203–206..