| Kreuznach Conference (August 9, 1917) Conférence de Kreuznach (9 août 1917) | |

|---|---|

The Parkhotel Kurhaus in Bad Kreuznach, headquarters of the Oberste Heeresleitung, from January 2, 1917 to March 8, 1918. | |

| Genre | Strategy meeting |

| Date(s) | 9 august 1917 |

| Location(s) | Bad Kreuznach |

| Country | German Empire |

| Participants | Georg Michaelis Richard von Kühlmann Paul von Hindenburg Erich Ludendorff |

The Kreuznach Conference on August 9, 1917, was a German government conference that aimed to draft the Reich Government's[nb 1] response to the proposals made on August 1, 1917, by Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Ottokar Czernin for negotiating an honorable way out of the conflict. Additionally, the conference served as the primary meeting between the new Imperial Chancellor, Georg Michaelis, and the two main leaders of the German High Command, Erich Ludendorff[nb 2][1] and Paul von Hindenburg. At this meeting, the military tried to impose the war aims they set for the conflict on the members of the civilian government, based on the minutes of the April 23, 1917 conference.

Context

Crisis of July 1917

After Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg's dismissal on July 13, Georg Michaelis took his place as the next German Chancellor. However, he quickly became known as a mere figurehead for Hindenburg and Ludendorff, who were both opposed to the previous Chancellor's domestic reform initiatives[2] and war objectives.[3]

After a subdued power struggle between an inadvertent coalition composed of the Oberste Heeresleitung, Kronprinz Wilhelm, and the political parties,[3] and Imperial Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, the latter was ousted by Wilhelm II.[4] Despite being deposed, the previous chancellor was able to appoint his successor, Georg Michaelis, who was serving as the Supply Commissioner in the Prussian cabinet. Proposed by Georg von Hertling, President of the Bavarian Council, he was admired by Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff for his frankness.[1]

The Chancellor was removed from office due to the dual concerns of domestic reform in both the Reich and Prussia, as well as war objectives. The formulation of the war objectives program was a primary factor in the breakdown of relations between the Chancellor and the military. According to Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, the outcomes of the April 23 meeting seemed unrealistic, despite his prior approval. He believed that the war objectives established during the conference were unachievable.[2]

Austro-German discussions

_1918.jpg.webp)

Charles I's ascension to the throne altered the nature of the connections between the Reich and the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy. The young monarch departed from the German policy of his predecessor by no longer following it blindly.[3] Rather, he made numerous contacts in an effort to resolve differences between Germany and Austria-Hungary, often without success. Additionally, he informed his German counterparts that the dual monarchy could not stay involved in the conflict, demonstrating his new vision for the alliance between Austria-Hungary and Germany.[5][6] Finally, Emperor Charles' attempts at parallel diplomacy exemplify Austro-Hungarian efforts to reduce the Reich's control.[7]

In response, the Germans vehemently opposed any peace[8] initiatives proposed by their Austro-Hungarian counterparts and instead doubled-down on their Eastern policy in the Baltic states, Poland, and Ukraine.[9] Thus, German representatives sought to achieve their war objectives by promoting the emergence of separatist movements in Ukraine and the Baltic states, using the fiction of local support.[10] This strategy was in line with the objectives formulated in Bingen a few days earlier. Similarly, negotiations between Germany and Austria-Hungary aimed to integrate Poland, Romania, and Ukraine into a vast economic bloc under Reich control. As a result, the Austro-Hungarian negotiators had limited room for maneuver and were only able to negotiate their share of influence within the German-led Mitteleuropa.[10]

Consequently, the German-Austro-Hungarian alliance was reinforced. Ottokar Czernin attempted to advocate for the point of view of the dual monarchy in bilateral discussions, while publicly displaying complete agreement with German positions. This tactic compelled the Austro-Hungarian minister to concede to German proposals whenever his German counterparts demonstrated their unwavering stance. In the face of a growing power imbalance against the dual monarchy, Ottokar Czernin ensured the strength of the German-Austro-Hungarian alliance by denouncing any attempts to negotiate with the Allies as "treason".[11]

Participants

The meeting was initiated by the new Reich Chancellor, Georg Michaelis, and chaired by him.

It brought together Richard von Kühlmann,[nb 3][12][13] the new State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, and the Dioscuri, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff, representatives of the High Command.[13]

Discussions

Divergent war aims

Upon opening the conference, the Chancellor agreed to the "Kreuznach Agreement" terms of April 23, 1917, which were imposed by the Dioscuri.[14] Before this agreement, the military regularly reminded the new Chancellor of these terms.[14]

Nevertheless, this accord regarding German expansion covered up civil disagreements, primarily those between Richard von Kühlmann and the military. The inexperienced chancellor initially wavered on which direction to take, but ultimately aligned with the military's stance.[15] Erich Ludendorff championed multiple annexations throughout Europe, including Belgium, France, and Poland.[14]

Economic warfare objectives were also a source of contention between civilians and the military. Civilians preferred to return to pre-war trade practices, specifically implementing the most-favored-nation clause in Europe with priority given to German companies. They believed that free access to the world market was the main objective of the German war. This could be achieved through multilateral agreements, or even customs unions between the Reich and its neighbors, which would provide access to vital raw materials necessary for the Reich's economic development.[16] As part of a program to reintegrate the Reich and its allies into the global economy, Erich Ludendorff initiated an economic program for the first time, geared towards building an autarkic economy around the Mitteleuropa economic bloc. The annexations he advocated aimed to directly control the Lorraine and Polish steel basins, and create a protective glacis for these resource-rich mining regions. Furthermore, Dioscure envisioned enhancing political and economic connections with the Netherlands and its empire. This would strengthen their relationship with Europe, whereby many German maritime bases would be established.[17]

Oriental program

The conference participants proposed an expansionist policy towards a Russia experiencing internal decomposition. They suggested that the Ukraine and the Baltic states, including the governments of Estonia, Livonia, and Courland, should be detached from Russia.[10]

The program defined in Bingen on July 31 was forcefully reaffirmed by the Dioscuri. The Baltic territories of the Russian Empire piqued the interest of the attendees. Estonia, Livonia, Courland, Lithuania, and Finland were planned to be incorporated into the German zone of influence. Furthermore, the German government and military were strategizing to gain command over Ukraine's agricultural and mining resources, in addition to their northern expansion plans.[10]

Finally, the question of Poland, which was occupied by the Reich and the dual monarchy,[nb 4] was once again discussed by the participants. They were unsure of the best course of action for taking control of the region after the withdrawal of Austro-Hungarian troops. Two options were presented to the Polish representatives in the Reich: either the annexation of their territory under the new Reichsland[nb 5] or the establishment of formal independence through the creation of a German defensive glacis extending to the outskirts of Warsaw.[nb 6][18]

Western program

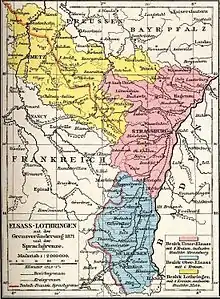

Agreement was also reached on the expansionist projects in Western Europe, specifically in Alsace-Lorraine, Belgium, Luxembourg, and French Lorraine. Various options were being considered by civilians and military personnel to further integrate Reichsland into the Reich. On August 9, several programs were discussed. According to participants, the outright annexation of the Kingdom of Prussia was considered the best approach to definitively integrate the Reichsland[nb 7] into the Reich. However, it faced opposition from the majority in the Reichstag, who preferred the creation of a 26th federal state. To overcome this obstacle, the military proposed the establishment of a new state,[nb 8] but its internal independence would be restricted by the implementation of "specific economic and administrative measures" to integrate it into Prussia: one of which included the Prussian-Hessian railways taking control of the Alsace-Lorraine railway company, an action supported by the Dioscuri.[10]

The Reich also had plans to partition Belgium. In compliance with the April-defined program, the Reich was designated to uphold an occupation force on Belgian territory for an extended duration as ensured by the peace treaties. Moreover, the Flemish coastline and the Liège region[19] were to be directly added to the Reich to create a safeguarding glacis for the industrial area of Aachen. Finally, to economically connect the kingdom to the Reich, the Belgian rail network would come under management by the Prussian railway administration.[18]

German officials viewed the region including Luxembourg and French Lorraine as a unified economic entity. Influenced by representatives of the iron and steel industry, the Chancellor and the Dioscuri aimed to incorporate the Lorraine iron and steel basin into the Reich.[18] Accordingly, the Longwy-Briey mining basin was to be annexed to the Reich and passed on to Prussia.[14] In the face of Kühlmann's skepticism, different options were examined. While the possibility of outright annexation was considered, all involved saw the purchasing of the French shareholding in the Lorraine mines as a viable alternative, thereby linking the Lorraine steel basin to the German economy.[18]

Issue

Maintaining war aims

The Dioscuri, the Chancellor, and the Secretary of State aimed to establish a political, military, commercial, and economic entity under the control of the Reich with a strong structure based on the quadruplice.[nb 9][13]

This program was built upon the concept of Mitteleuropa, which was introduced by Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg on September 9, 1914, in his war aims program on behalf of the German government. On August 9, the project was restructured based on the territorial bloc established by the Reich and its allies. The military alliance was to be augmented by an "economic alliance", creating an economic bloc that expands "from the North Sea and the Baltic to the Red Sea".[18]

Eviction of the dual monarchy

During the conference, German leaders agreed to subject the dual monarchy to strict political, economic, and military control. This process, known as "vassalization",[nb 10] involved gradually removing Austria-Hungary's influence from all territories where its impact was felt.[10]

In Poland, the Dioscuri and the Chancellor aimed for the Austro-Hungarian withdrawal from Russian Poland. The Austro-Hungarian occupation authorities were to be replaced by the German occupation authorities, facilitating Poland's reunification during the conflict, all under the strict political control of Germany. The German government would establish Duke Albrecht of Württemberg as regent of the kingdom.[18]

Additionally, to appease Ukrainian separatists, the Reich government aimed to compel its ally, who was growing weaker due to the prolonged conflict, to relinquish Bukovina and the eastern portion of Austrian Galicia, which were mainly populated by Ukrainians.[10]

Coordination of German expansionist policy

To achieve their massive expansion goals, German leaders aimed to tightly control Belgium and its coastal areas without specifying the precise form of domination.

On the eastern side, conference attendees, both civilian and military, advocated for coordinated civilian-military action in support of all separatist movements in the Baltic regions and Ukraine. Georg Michaelis suggested the formation of "freely elected" committees composed of individuals sympathetic to the central powers to organize "spontaneous" demonstrations by pressure groups.[10]

The resulting states would only have formal independence, with German tutelage manifesting primarily in the legal and military domains. The laws enforced in those states would merely follow those in effect in the Reich, and their armies would have to adhere to all Prussian military regulations.[10]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Between the proclamation of the German Empire in 1871 and its dissolution in 1945, the official name of the German state was Deutsches Reich, subsequently referred to by the legal term Reich.

- ↑ These two soldiers appear inseparable, like the Dioscuri of Roman mythology.

- ↑ He took up his post on August 7, 1917.

- ↑ The Polish territories conquered from Russia were divided into two zones of occupation, each administered by a Governor General, one German and one Austro-Hungarian.

- ↑ A Reichsland is a territory integrated into the German Empire, but administered jointly on behalf of the 25 federal states.

- ↑ The question of the size of the Polish territories to be annexed has poisoned relations between civilians and the military since the outbreak of hostilities.

- ↑ In accordance with the german imperial constitution, Alsace-Lorraine, annexed in 1871, is a Reichsland.

- ↑ Expression used by Fritz Fischer.

- ↑ The Quadruplice comprises the Reich and its allies, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria.

- ↑ In the words of Fritz Fischer.

References

- 1 2 Fischer 1970, p. 408.

- 1 2 Mommsen 1968, p. 48.

- 1 2 3 Fischer 1970, p. 406.

- ↑ Fischer 1970, p. 409.

- ↑ Lacroix-Riz 1996, p. 27.

- ↑ Fischer 1970, p. 352.

- ↑ Bled 2014, p. 284.

- ↑ Fischer 1970, p. 411.

- ↑ Fischer 1970, p. 413.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Fischer 1970, p. 415.

- ↑ Bled 2014, p. 289.

- ↑ Fischer 1970, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Fischer 1970, p. 414.

- 1 2 3 4 Soutou 1989, p. 578.

- ↑ Fischer 1970, p. 412.

- ↑ Soutou 1989, p. 582.

- ↑ Soutou 1989, p. 583.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fischer 1970, p. 416.

- ↑ Soutou 1989, p. 579.

Bibliography

- Bled, Jean-Paul (2014). L'agonie d'une monarchie: Autriche-Hongrie 1914-1920 (in French). Paris: Taillandier. ISBN 979-10-210-0440-5.

- Fischer, Fritz (1970). Les Buts de guerre de l'Allemagne impériale (1914-1918). Geneviève Migeon et Henri Thiès. Paris: Éditions de Trévise. BNF 35255571j.

- Lacroix-Riz, Annie (1996). Le Vatican, l'Europe et le Reich: De la Première Guerre mondiale à la guerre froide. Références Histoire (in French). Paris: Armand Colin (published 2010). ISBN 2-200-21641-6.

- Mommsen, Wolgang J. (1968). "L'opinion allemande et la chute du gouvernement Bethmann-Hollweg". Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine (in French). 15 (1): 39–53. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1968.3328.

- Renouvin, Pierre (1934). La Crise européenne et la Première Guerre mondiale. Peuples et civilisations (in French). Vol. 19. Paris: Presses universitaires de France. BNF 33152114f.

- Soutou, Georges-Henri (1989). L'Or et le sang: Les Buts de guerre économiques de la Première Guerre mondiale (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 2-213-02215-1.