Krunski Venac

Крунски Венац | |

|---|---|

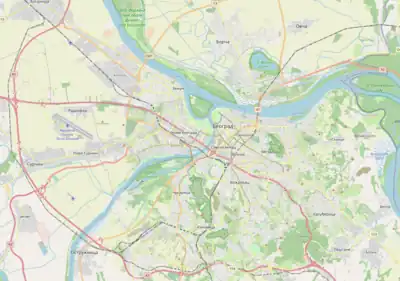

Krunski Venac Location within Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°48′16″N 20°28′17″E / 44.804497°N 20.471250°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Belgrade |

| Municipality | Vračar |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

Krunski Venac (Serbian: Крунски Венац) is an urban neighborhood of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is located in Belgrade's municipality of Vračar. In May 2021, the neighborhood was protected as the spatial cultural-historical unit.[1]

Location

Krunski Venac is located along the Krunska street after which the neighborhood got its name (Serbian for "coronation street"), in the northern part of Vračar, stretches to the neighborhood of Kalenić.[2]

History

19th century

At the corner of modern Krunska and Kneza Miloša streets, Jevrem Obrenović, brother of the ruling prince Miloš Obrenović, built the large house in the first half of the 19th century, and the spacious flower garden. Kept by his wife Tomanija, it was considered the most beautiful private garden in Belgrade at the time. The plants were imported from Turkey, Wallachia, Austria and France. In time, the area became known among the Belgraders as the "Corner at Mrs. Tomanija". The residence itself became the center of the cultural events in the city and one of the most visited houses in Belgrade.[3]

In 1880s, the later famous kafana Tri lista duvana ("Three tobacco leaves") was opened on the corner of the Kneza Miloša street and Bulevar Kralja Aleksandra. A bit later, the first telephone exchange in Belgrade was installed in the venue.[4]

20th century

One of the best preserved sections of "Old Belgrade", Krunska Street is considered to be one of the most distinguished areas in Belgrade, after the Civil Engineering Law from 1900 allowed only villa-type houses to be built in the area of Krunski Venac. From 1900 to 1903 the street was named after queen Draga.[5]

In 1920, the Society for the Construction of Catholic Church in Belgrade was founded. Since 1924 it has been headed by the archbishop of Belgrade Ivan Rafael Rodić who organized numerous charity gatherings to collect funds for the future Roman Catholic cathedral in Belgrade. City administration donated the parcel in Krunski Venac, bounded by the streets of Kičevska, Mileševska and Sinđelićeva, or roughly where the modern Park Vojvoda Petar Bojović is today. The Archdiocese was very satisfied with the location of the land lot, however the problem of ownership surfaced. The city donated the lot which he didn't officially own, so the plans failed, causing severe protests by both the Society and the Archdiocese. Collected money was then used to expand the Saint Ladislav Chapel in 1925-1926, which since 1924 functioned as the temporary cathedral of the Archdiocese. Proper Roman Catholic cathedral in Belgrade, after continuous failed offering of various locations during the Interbellum, was ultimately never built.[6]

A monument to vojvoda Petar Bojović was placed in the park, today called after him, in 1993. The bust is work of Drinka Radovanović. The monument was fully renovated in 2020.[7]

21st century

The name of the neighbourhood, just like the adjoining Grantovac, later fell into obscurity and is not used much today. One of the rare official usage is for one of the exchanges of Telekom Srbija, until it resurfaced in the late 2010s in the media, regarding demolitions in the neighborhood.

In August 2018 part of the neighborhood was placed under the protection.[8] Concurrently, private investors announced partial demolition of the eastern section of the neighborhood (around the streets of Topolska, Petrovgradska and Vojvode Dragomira) and construction of several highrise buildings in the area. Inhabitants of Vračar organized, protesting against the project and stressing the necessity of preserving such refined ambient entireties. Architect Bojan Kovačević, president of the Serbian Academy of Architecture, said that "there are parts of the city which are docile units, and which can't resist the pressures from the investors. In the Topolska Street, someone is trying to capitalize on the ambient fineness by constructing the buildings which kill that very fineness".[9] Deputy mayor Goran Vesić said that he supports the motion for preserving the old neighborhood.[8]

Still, the demolition began. In September 2018, the 1927 villa, designed by Milan Štangl, was demolished. It was considered one of the earliest representatives of the moderna in Belgrade. It was demolished to make way for a residential building.[10] Only after it was demolished, the city decided to draft the detailed regulatory plan for the eastern section of the neighborhood which stipulates that the façades of the new buildings must be in accordance with the "ambient unit" of the neighborhood, and can't have modern glass-like façades, for example.[11] The villa continued to make headlines, including the summer and fall of 2021. It was disclosed that the investor had no permits for the various adaptations and additions, including the construction of elevator shaft in the building's skylight. Several inspections ordered halting of the works and restoration of previous appearance, but the investor ignored them and street protests of the neighbors continued.[12][13][14]

At Resavska 25, just below the crossing with the Krunska, there was a House of Pera Velimirović, built in 1908. Two-floor house was designed by Jovan Ilkić for prime minister Petar Velimirović. Despite the house was placed under the preliminary protection as the future cultural monument, it was demolished in June 2020 by the private investors. Public and architects were outraged, director the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments claimed that the investors had no green light to do it, other members of the Institute stated that the director issued the permit for demolition on her own breaking the law, but the building was leveled to the ground anyway to make room for the generic commercial building.[15][16][17] In December, the same investor demolished another, even older house from the 19th century, on the lot adjoined to the already demolished building.[18]

In September 2020, city announced plan for tearing down the entire block bounded by the Krunska, Smiljanićeva, Kneginje Zorke and Njegoševa street. It covers 1.8 ha (4.4 acres). Demolition of the old buildings, including the Museum of Natural History, was planned, which were to be replaced with the modern, much higher residential-commercial buildings. After strong negative public, experts' and political reaction, only few days later city administration abandoned the plans.[19][20] City then suggested to the government to protect this specific block, which the government did in April 2021, declaring this part of Krunski Venac a spatial cultural-historical unit. The neighborhood was described as specific, with authentic appearance of ground floor houses, which were built at the same time (early 20th century) and in the same style. As such, they make a "harmonious ambiance and priceless heritage and testament" in development of Belgrade.[21]

Number of appeals and pressure by the local heritage organizations, and celebrities and public figures grew by the end of 2021, pressuring the government to stop dragging the decision on extending protection to the entire Krunski Venac area. The motion was held by the government for months.[22]

Despite the protection, construction in Topolska continued,[23] while in August 2022 city restored the plan for the demolition in the Krunska-Smiljanićeva-Kneginje Zorke-Njegoševa section, and construction of higher buildings. The plan was opened for public insight but was abruptly withdrawn the next day.[24][25] In February 2023, the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments declared another villa purchased by the investors, at 18 Petrogradska Street, of having absolutely no value, and that it can be demolished to make way for a modern three-storey building.[26]

Landmarks

Nikola Tesla Museum

The Nikola Tesla Museum is located in the neighbourhood. On 12 July 2007, Tesla's fountain was opened on a lawn outside the Museum, marking the 115th anniversary of the "Belgrade Waterworks", the city's official plumbing and sewage company. It was made after the original project of Nikola Tesla, patented in 1913, using a pump which uses very little electricity. It took 25 years for researchers to fully understand Tesla's idea and create a fountain like this. At the time, Tesla collaborated on the design of the fountain with the famed US stained glass artist Louis Comfort Tiffany.[27]

Students Polyclinic

On the corner with the Braće Nedić street, one of the "most elegant" buildings in Belgrade was built in 1923/1924, with the purpose of being the largest and the most modern privately owned health institute in the Balkans. During the heavy "Easter bombing" of Belgrade by the Allies on 16 April 1944. the hospital was hit and over 50 people were killed, including 22 mothers and 22 newborns, several visiting family members and several medical workers. Since the mid 1950s the "Institute for the student's health protection Belgrade" has been located in the building, which is colloquially known as the Students' polyclinic. Memorial plaque for the 1944 event was dedicated on 16 May 2017.[28]

In February 2021, the new master plan by the Ministry of Health envisioned abolishment of the student polyclinics, and their annexation to the regular, community healthcare centers. Negative backlash, both by the citizens who rejected an instant influx of 100,000 new patients into the regular healthcare system which is overstretched as it is, and by the students, resulted in the petition of 35,000 signatories in only two days, and protests by the students in front of the ministry building. Minister Zlatibor Lončar verbally clashed with the students accusing them of being political, but both he and the prime minister Ana Brnabić then announced that the plan will not be implemented and that students medical centers will remain as they were.[29][30]

Protection

The neighborhood was placed under the legal protection in May 2021 as one of Belgrade's spatial cultural-historical units. Protected area includes the streets of Topolska, Petrogradska, Krunska, Vojvode Dragomira and sections of Mileševska, Maksima Gorkog and Novopazarska. The area was described as the "part of the wider city center, mostly residential, which was formed in the first decades of the 20th century. The area and the individual buildings have cultural, historical and architectural values, as testament of the urban, economic and social development of the capital during Interbellum, but also of the certain style of living of its residents."[1]

References

- 1 2 Daliborka Mučibabić (22 May 2021). Крунски венац и Светосавски плато - културна добра [Krunski Venac and Santi Sava Plateau - cultural monuments]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ↑ Miloš Lazić (12 June 2018). "Kafana po glavi stanovnika" [Kafana per capita]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ↑ Goran Vesić (4 February 2020). Варош београдска [Belgrade town]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16.

- ↑ Goran Vesić (14 September 2018). "Прва европска кафана - у Београду" [First European kafana - in Belgrade]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- ↑ Marija Brakočević & Dejan Aleksić (21 February 2016). "Bulevar kralja Aleksandra – moderna avenija sa šarmom prošlosti" (in Serbian). Politika. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ↑ Goran Vesić (20 March 2020). Католичка катедрала које нема [Catholic cathedral which doesn't exist]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (5 December 2020). "Obnovljeni spomenici kralju i vojvodama" [Monuments to king and vojvodas were renovated]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- 1 2 Beoinfo (4 September 2018). "Vesić: Podržavam zahtev, sačuvati ambijentalne celine grada" [Vesić: I support the motion, we should preserve the ambient parts of the city] (in Serbian). N1. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ "Kovačević: Pitomi delovi grada pod pritiskom investitora" [Kovačević: Docile parts of the city under the investors' pressure] (in Serbian). N1. 27 August 2018. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ N1, FoNet (12 September 2018). "Počelo rušenje vile iz 1927. godine u Topolskoj" [Demolition of the 1927 villa in Topolska began] (in Serbian). N1. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Branka Vasiljević, Dejan Aleksić (26 September 2018). "Престоница добија предуѕеће за метро" [Capital got a subway company]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (21 September 2021). "Investitor mora da ukloni nelegalno izvedene radove" Инвеститор мора да уклони све урађено ван дозволе [Investor has to remove everything done outside of the permits granted]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 18. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (22 September 2021). "Krivične prijave protiv odgovornih na gradilištu u Topolskoj 19" [Criminal charges against responsible ones on the 19 Topolska construction site]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (25 September 2021). Врачарци опет протестују због виле у Тополској 19 [Vračar residents protesting again because of the 19 Takovska villa]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ↑ Milica Rilak (16 June 2020). "Počelo rušenje kuće u Resavskoj: Kome treba kulturno nasleđe" [Demolition of house in Resavska began: who needs cultural heritage anyway] (in Serbian). Nova S. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ↑ Milena Ilić Mirković (19 June 2020). "Nastavljeno rušenje u Resavskoj: "Nestaje istorija Beograda"" [Demolition in Resavska continued: "Belgrade's history disappearing"] (in Serbian). Nova S.

- ↑ Milan Janković (22 June 2020). Један од пет - Рушење културе [1 to 5 - Demolition of culture]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ↑ N1 (28 December 2020). "N1: U centru Beograda srušena kuća iz 19. veka, investitor tvrdi da ima dozvolu" [N1: 19th century house in downtown Belgrade demolished, investor claims he obtained all permits] (in Serbian). Nova Srpska Politička Misao. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Заустављени урбанистички планови на Врачару [Urban plans for Vračar abandoned]. Politika (in Serbian). 28 September 2020. p. 14.

- ↑ N1 Beograd (28 September 2020). "Arhitekta o planu za rušenje zgrada na Vračaru: Nešto tu "debelo" nije u redu" [Architect on demolition plan for Vračar: Something is deeply wrong about it]. N1 (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (14 April 2021). "Kuće u Smiljanićevoj ulici pod zaštitom" [Houses in Smiljanićeva Street under protection]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 19. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ B.H. (13 December 2021). Одбрана Крунске улице од дивље градње [Defending Krunska Street from wild urbanism]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16.

- ↑ Beta (28 February 2022). "Udruženja: Ponovo radovi na vili u Topolskoj 19, iako je država zaštitila" [Association: works on villa in 19 Topolska Street continues, despite the state protection] (in Serbian). N1. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (5 September 2022). Изненадна обустава јавних увида [Abrupt suspension of public insights]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 13.

- ↑ Nevena Petaković (31 August 2022). "Višespratnice u Krunskoj: Šta sve krije nacrt koji je nestao sa sajta Beograda" [Highrise in Krunska: what hides the draft which disappeared from the City of Belgrade's site] (in Serbian). Nova Ekonomija. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (25 February 2023). "Zgrada umesto kuće u Petrogradskoj ulici" [Building instead of a house in Petrogradska Street]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ↑ Politika daily, July 13, 2007, page 44

- ↑ A.V. (17 May 2017), "Devet i po decemija poliklinike u Krunskoj", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ Ana Vuković (23 February 2021). Студентске поликлинике неће бити укинуте [Students polyclinics will not be abolished]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16.

- ↑ Beta (21 February 2021). "Sakupljeno skoro 35.000 potpisa za peticiju "Ne damo Studentsku polikliniku"" [ALmost 35,000 signatures for the petition "We are not giving up on Students Polyclinic"] (in Serbian). N1. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.