In the coinage of the North Indian and Central Asian Kushan Empire (approximately 30–375 CE) the main coins issued were gold, weighing 7.9 grams, and base metal issues of various weights between 12 g and 1.5 g. Little silver coinage was issued, but in later periods the gold used was debased with silver.[1]

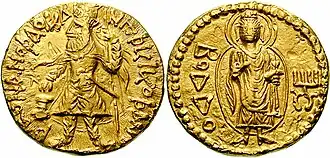

The coin designs usually broadly follow the styles of the preceding Greco-Bactrian rulers in using Hellenistic styles of image, with a deity on one side and the king on the other. Kings may be shown as a profile head, a standing figure, typically officiating at a fire altar in Zoroastrian style, or mounted on a horse. The artistry of the dies is generally lower than the exceptionally high standards of the best coins of Greco-Bactrian rulers. Continuing influence from Roman coins can be seen in designs of the late 1st and 2nd century CE, and also in mint practices evidenced on the coins, as well as a gradual reduction in the value of the metal in base metal coins, so that they become virtual tokens. Iranian influence, especially in the royal figures and the pantheon of deities used, is even stronger.[2] Under Kanishka the royal title of "King of kings" changed from the Greek "ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΝ" to the Persian form "ϷAONANOϷAO" (Shah of Shahs).[3]

Much of what little information we have of Kushan political history derives from coins. The language of inscriptions is typically the Bactrian language, written in a script derived from Greek. Many coins show the tamga symbols (see table) as a kind of monogram for the ruler. There were several regional mints, and the evidence from coins suggests that much of the empire was semi-independent.

Kushan deities

The Kushan religious pantheon is extremely varied, as revealed by their coins and their seals, on which more than 30 different gods appear, belonging to the Hellenistic, the Iranian, and to a lesser extent the Indian world. Greek deities, with Greek names are represented on early coins. During Kanishka's reign, the language of the coinage changes to Bactrian (though it remained in Greek script for all kings). After Huvishka, only two divinities appear on the coins: Ardoxsho and Oesho (see details below).

Representation of entities from Greek mythology and Hellenistic syncretism are:

- Ηλιος (Helios), Ηφαηστος (Hephaistos), Σαληνη (Selene), Ανημος (Anemos). Further, the coins of Huvishka also portray the demi-god erakilo Heracles, and the Egyptian god sarapo Sarapis.

The Indic entities represented on coinage include:

- Βοδδο (boddo, Buddha)

- Μετραγο Βοδδο (metrago boddo, bodhisattava Maitreya)

- Mαασηνo (maaseno, Mahasena)

- Σκανδo koμαρo (skando komaro, Skanda Kumara)

- þακαμανο Βοδδο (shakamano boddho, Shakyamuni Buddha)

The Iranian entities depicted on coinage include:

- Αρδοχþο (ardoxsho, Ashi Vanghuhi)

- Aþαειχþo (ashaeixsho, Asha Vahishta)

- Αθþο (athsho, Atar)

- Φαρρο (pharro, Khwarenah)

- Λροοασπο (lrooaspa, Drvaspa)

- Μαναοβαγο, (manaobago, Vohu Manah)

- Μαο (mao, Mah)

- Μιθρο, Μιιρο, Μιορο, Μιυρο (mithro and variants, Mithra)

- Μοζδοοανο (mozdooano, Mazda *vana "Mazda the victorious?")

- Νανα, Ναναια, Ναναϸαο (variations of pan-Asiatic nana, Sogdian nny, in a Zoroastrian context Aredvi Sura Anahita)

- Οαδο (oado Vata)

- Oαxþo (oaxsho, "Oxus")

- Ooρoμoζδο (ooromozdo, Ahura Mazda)

- Οραλαγνο (orlagno, Verethragna)

- Τιερο (tiero, Tir)

Additionally:

- Οηϸο (oesho), long considered to represent Indic Shiva,[4] but more recently identified as Avestan Vayu conflated with Shiva.[5][6]

- Two copper coins of Huvishka bear a 'Ganesa' legend, but instead of depicting the typical theriomorphic figure of Ganesha, have a figure of an archer holding a full-length bow with string inwards and an arrow. This is typically a depiction of Rudra, but in the case of these two coins is generally assumed to represent Shiva.

Base metal issues

MacDowell (1968) identified three regional copper issues of Kajula Kadphises and Vima Taktu of separate coinage in their first issue, which would correspond to the three previous realms making up the Kushan empire. The northern area, Bactria which had the largest sized coins of 12 g (tetradrachms) and 1.5 g, Gandhara whose coinage weighed 9–10 g for large and 2 g for small, and the Indian area, where coins are 4 g each.

MacDowell (1960) proposed a gradual reduction of all three issues starting with Huvishka, while Chattopadhyay (1967) proposes a rapid devaluation of the issue by Kanishka. It seems that there were two reductions based on the coinage of the rulers just named.[7] Later issues were unified into a central coinage system of weights.

![Bronze coin of Vima Takto. Corrupted Greek legend ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΩΝ ΣΩΤΗΡ [ΓΗΕ.]: "The King of Kings, Saviour"](../I/Coin_of_Kushan_King_Vima_Takto.jpg.webp) Bronze coin of Vima Takto. Corrupted Greek legend ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΩΝ ΣΩΤΗΡ [ΓΗΕ.]: "The King of Kings, Saviour"

Bronze coin of Vima Takto. Corrupted Greek legend ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΩΝ ΣΩΤΗΡ [ΓΗΕ.]: "The King of Kings, Saviour"

Gold coinage

Vima Kadphises issued three denominations of for this metal, a two of 15.75 grams, one of 7.8 grams and a quarter dinar piece of 1.95 grams.[8]

Gold dinar of Kushan king Kanishka II (200–220)

Gold dinar of Kushan king Kanishka II (200–220)

Imitations

The coinage of the Kushans was copied as far as the Kushano-Sasanians in the west, and the kingdom of Samatata in Bengal to the east. Towards the end of Kushan rule, the first coinage of the Gupta Empire was also derived from the coinage of the Kushan Empire, adopting its weight standard, techniques and designs, following the conquests of Samudragupta in the northwest.[11][12][13][10] The imagery on Gupta coins then became more Indian in both style and subject matter compared to earlier dynasties, where Greco-Roman and Persian styles were mostly followed.[14][13][15] The standard coin type of Samudragupta, the first Gupta ruler to issue coins, is highly similar to the coinage of the later Kushan rulers, including the sacrificial scene over an altar, the depiction of a halo, while differences include the headdress of the ruler (a close-fitting cap instead of the Kushan pointed hat), the Garuda standard instead of the trident, and Samudragupta's jewelry, which is Indian.[9]

References

- ↑ "ONSNUMIS.ORG – Kshaharata Questions". 2021-08-03. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ↑ MacDowell, "Mithra"

- ↑ MacDowell, "Mithra", 308–309

- ↑ Sivaramamurti, pp. 56–59.

- ↑ Sims-Williams, Nicolas. "Bactrian Language". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 3. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ↑ H. Humbach, 1975, pp. 402–408. K.Tanabe, 1997, p.277, M.Carter, 1995, p.152. J.Cribb, 1997, p. 40. References cited in "De l'Indus à l'Oxus".

- ↑ "The Devaluation of Huvishka's Coinage". kushan.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ↑ "COINS OF KUSHAN DYNASTY". Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- 1 2 3 Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997). The Gupta Empire. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9788120804401.

- 1 2 Higham, Charles (2014). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Infobase Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 9781438109961.

- ↑ Sen, Sudipta (2019). Ganges: The Many Pasts of an Indian River. Yale University Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780300119169.

- ↑ Gupta inscriptions using the term "Dinara" for money: No 5–9, 62, 64 in Fleet, John Faithfull (1960). Inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings And Their Successors.

- 1 2 Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997). The Gupta Empire. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 30. ISBN 9788120804401.

- ↑ Pal, 78

- ↑ Art, Los Angeles County Museum of; Pal, Pratapaditya (1986). Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.–A.D. 700. University of California Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780520059917.