Kusumi Morikage | |

|---|---|

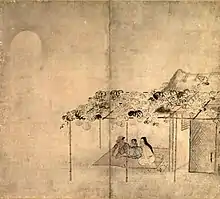

Staying cool under an arbour of evening glory | |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Years active | 1620-1690 |

| Era | Edo Period |

| Children | Kiyohara Yukinobu, Hikojuro |

Kusumi Morikage (久隅 守景, c. 1620–1690)[1] was a Japanese painter of the Edo period. He came from Kaga Province, the centre of the lands of the Maeda clan. He fell afoul of his teacher, Kanō Tan'yū, and became the Maeda clan's official painter. His sympathy for farmers and the poor people of the Edo period is reflected in his works.[1]

His daughter, Kiyohara Yukinobu (1643–1682), was also an artist, one of the few female painters of the Edo period.[2]

Background

Little is documented about Morikage’s career as an artist. It is apparent, however, that his skills were revered amongst the most talented Kanō pupils. His work was most prominent when he was commissioned as a proficient Kanō painter to paint the Landscape of the Four Seasons. Today, Morikage is best known as the Kanō pupil who departed from the famous school and its rigid beliefs to pursue individual expression. His passion is evident in the transformation of his conservative art style into one that captured cultural values of Edo Japan, ultimately creating art that held social value. Although his artistic career is not well chronicled, Kusumi Morikage can be considered a pioneer who visually conceptualised “rural manners and customs”.[3] Some notable works include: Family Enjoying the Evening Cool, Falconry Folding Screens and Farming in the Four Seasons.

Edo Period

Morikage is best known as a Kanō artist in the Edo period. This period was also known as the Tokugawa period (1603 – 1867), named after its founder, Tokugawa Ieyasu. In this era, Tokugawa created a nation that aimed for economic growth, political stability and social harmony in order to maintain overall peace and national prosperity.[4] In his shogunate (military dictatorship), determining that the nation was still susceptible to the influence of external ideas and interventions, Tokugawa implemented a long era of national seclusion to protect his rule from political and religious instability.

However, since it was vital to preserve social order in a way that would continue to sustain the nation and generate economic profit without external affiliations, the shogun tightened the reins on social order and outlawed movement between social classes. These social classes were divided into four groups - warriors, farmers, merchants and artisans, where farmers made up eighty percent of the population and were prohibited from engaging in activities that were non-agricultural.[4] In this way, the Tokugawa shogunate placed considerable importance on agricultural production, which became a sizeable source of income for those in places of power.

Farmers were thus viewed as vital to the stability of the economy, as their labour also paved the way to dynamic art cultures. One such dynamic art culture is found in Morikage’s sympathy with the social and political circumstances surrounding rural Edo Japan, as the agricultural industry’s labour fuelled Edo Japan's economy. This prominent theme is manifested in many of his artworks during later stages in his life.

Education

Kanō School

Morikage was often recognised as one of Tan’yū’s best four pupils in the Kanō School of Painting.[5] Also known as the Kanō School, this art academy was run by a family of artists who crafted a specific style of art considered to be politically ideal for many generations.[6] It was founded during a period where Chinese cultural ideals were popular. However, under the guidance of Kanō Motonobu, it incorporated the Japanese style of ink painting, thereby transforming it into the “Kanō style”.[6]

Style

Initially, when the school was founded, Kanō Masanobu adopted the Chinese painting style favoured by Zen philosophy - depicted by strong brushwork, dominant use of ink and minimal use of pigments.[7] It is thought that Masanobu implemented this style in order to maintain a favourable political standing with the shoguns of that time.[7] As generations passed, this style continued to develop and evolve to include bold use of colour, native Japanese motifs and decorative embellishments to continue to appeal with the wealthy merchants and ruling classes.[7]

It was later under Kanō Tan’yū that the school developed a strict art regime with high academic standards. The Kanō School of Painting became known as the official school of painting in Japan during the Edo period.[5] Due to strong affiliations with the Tokugawa shogunate, Kanō Tan’yū established an art style that was ‘consistent with the Tokugawa’s emphasis on social control’,[7] holding a strong preference for lucrative production over individual interpretation.[7] Morikage’s education in Kanō School thus arrived in the form of various academic expectations and rigorous teaching styles. As expected of Kanō students, Morikage trained under Tan’yū to create an art style that was politically rigid.

After spending some time as Tan’yū’s pupil, the artist came to rebel against the core principles of Kanō School, abandoning strict Kanō laws and traditions to instead pursue spirited creativity. His vision posed a threat to Kanō academicism and ultimately led to Morikage’s estrangement from Tan’yū.[8] When Morikage was cast out by his master, Kanō Tan’yū, he was appointed as the official painter for the Maeda Clan of the Kaga Province.[9] The artist then became known as the celebrated Kanō school student who left the academy to pursue his desire for individual expression.

Maeda Clan

The Maeda Clan was a powerful family from the Kaga Province that stood second in power to the ruling Tokugawa family.[10] They were allies with the Tokugawa family and maintained a stable relationship all throughout the Edo period. As a result, the Kaga domain also held strong ties with Kanō school’s artists.[11] It is thus assumed that Morikage’s connection to the Maeda family was formed when he contributed to work on painting the fusuma (sliding door), Landscape of the Four Seasons, in the clan’s family temple, Zuiryuji.[11] Today, Landscape of the Four Seasons is a notable artwork that reflects the deep ties between the Maeda Clan and Kanō School.

This affiliation also played an important role in the progression of Morikage’s artistic career. When Morikage relocated to Kaga after being cast out by Tan’yū, he resided in Kanazawa, and formed important relationships with Maeda lords, Imaeda and Obata families, as well as the city magistrate, Kataoka Magobee.[11] It is said that during this time in Kaga, Morikage experienced a major leap in his art career.[11] The artworks Ritual of Racehorse at Kamigamo Shrine and Picking Tea at Uji are believed to be some of Morikage’s best artistic successes, painted during his stay in Kanazawa.

Themes

The significance of the agricultural industry in Edo Japan is reflected in many of Morikage’s works. His main source of inspiration comes from the increasingly important role of farmers in cultivating rice, as well as the changing cultural norms of “family” and familial relationships. In the Tokugawa period, taxes were levied in rice.[12] For most farmers, rice thus became a symbol of pain and pride, and the ‘sustenance of the Japanese soul’.[12] As farmers became vital in providing a continuous source of income for the economy, Morikage’s empathy for them grew and realised itself in the form of capturing the daily life of Japanese farmers. This theme is also resonant in the works of Hanabusa Itchō (1652 - 1724), who similarly departed from the Kanō school and came to be known for painting the ‘customs of city life or pastoral villages’.[8]

Personal life and family

The Kanō school highly valued ‘kinship ties’, as they formed strong, affinal relationships.[11] Kusumi Morikage’s talent was held in such high regard by his master, Tan’yū, that the artist was eventually married into Tan’yū’s family.[11] Through this marriage, Morikage was officially recognised as a member of the Kanō family, marking a noteworthy stage in Morikage’s life. Although these successes also followed his children, it’s suspected that their later transgressions eventually stripped Morikage of his status as an official painter.[13]

Kiyohara Yukinobu

Morikage’s daughter, Kiyohara Yukinobu (1643 - 1682), developed an artistic reputation that was well-received and recognised by numerous artists at the time. Yukinobu’s popularity as an artist was often defined by her elegant style and feminine delicacy in the use of line and colour. Her accomplishments are said to have stemmed from Tan’yū’s traditional Kanō teachings, and came to be known as the most celebrated female artist in the Kanō School of Painting.[11] During her time as a Kanō pupil, Yukinobu is said to have later eloped with another student in Tan’yū’s atelier.[13]

Hikojuro

Also a Kanō student who studied under Tan’yū, Hikojuro was a talented painter who was admonished for frequenting houses of ill reputation, such as the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter,[8] and was eventually exiled to Sado Island after showing hostile behaviour towards another student.[13] However, despite this tumultuous reputation, it’s understood that Hikojuro continued to receive commissions for paintings even while in exile due to his faithful mastery of Kanō teachings and traditions.[11]

Notable works

Morikage’s profound and intriguing view of the world was evident in his vivid depictions, including animals rendered with human expressions and plants brought to life with curious and expressive brush strokes.[11] Examining his most notable artworks reveals his ‘rich array of ideas’ and ‘breadth of his artistic terrain’.[11]

Family Enjoying the Evening Cool

Family Enjoying the Evening Cool is Morikage’s most notable folding screen painting as it indicates that Morikage depicted happiness in a family structure that was not common at the time.[13] The nuclear family depicted in this painting - a husband, wife and child - reflects major rural familial changes that occurred in the beginning of the seventeenth century.[13] Considered a national treasure, this painting illustrates a peasant family using a combination of fine brushwork, rough brush strokes as well as dilute ink.[3]

Additionally, other than visualising a unique take on rural and familial structures in Edo Japan, it is also proposed that Morikage was inspired by a waka poem by the poet Kinoshita Katsutoshi (1569 - 1649), otherwise known by his pen name, Chōshōshi.[13] Another study observes that the painting is constructed with ‘eremitic recluse ideas that would have been learned in a Chinese style education’, found in motifs such as the gourd.[13] The overall significance of this piece in rendering a peaceful peasant family amidst agricultural crisis prompted its selection for the Tokyo National Museum exhibition in 2001.

Falconry Folding Screens

Falconry Folding Screens is regarded as one of the most important pieces by Kusumi Morikage.[9] The painting largely illustrates falconry, while other birds such as swans and cranes are also hunted – depicting a scene that would be common in the Tokugawa family.[9] The realist renditions of the birds and the people on the folding screen appear to be reminiscent of Tan’yū’s style. While the screen is adorned with Mitsuba-aoi crests of the Tokugawa family, it also depicts various trees, of which plum trees were often associated with the Maeda family’s crest.[9] The artwork is an important piece as it demonstrates a connection between the Maeda and Tokugawa families.

Farming in the Four Seasons screens

Painted as a pair of six folding screens, Farming in the Four Seasons depicts rural customs in Japan, representing Morikage’s sympathy for the agricultural industry. Peasants are illustrated to be working in the fields to produce crops over the span of four seasons, Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter.[11] However, the order of the seasons are reversed, showcasing Morikage’s art style as a personal touch on a classical subject and reveals a vision that set Morikage apart from other artists of his time.[11]

Gallery

View of West Lake

View of West Lake Seven Sages of Bamboo Grove

Seven Sages of Bamboo Grove Agriculture in the Four Seasons

Agriculture in the Four Seasons A Samurai on Horseback

A Samurai on Horseback Staying Cool Under an Arbour of Evening Glory

Staying Cool Under an Arbour of Evening Glory Emperor Yao Visiting Yu Chonghua

Emperor Yao Visiting Yu Chonghua

References

- 1 2 The Great Japan Exhibition: Art of the Edo Period 1600–1868, ISBN 0-297-78035-2

- ↑ "Quail and Millet". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- 1 2 "Family enjoying the evening cool". Emuseum.jp. n.d.

- 1 2 "Tokugawa period". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 2019.

- 1 2 "Kusumi Morikage". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 2015.

- 1 2 "Kanō school". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (2018).

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Kano School of Painting". Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2003). Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

- 1 2 3 Johei, S (1984). "The Era of the Kanō School". Modern Asian Studies. 18 (Modern Asian Studies): 18(4), 647–656. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00016358. JSTOR 312341.

- 1 2 3 4 Uchiyama (2016). "BIJUTSUSHI" (PDF). Journal of Japan Art History Society. 66 (1): 1–17.

- ↑ "Maeda Family". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "KUSUMI MORIKAGE: From Adversity, a Gentle Gaze at Familiar Things". Suntory Museum of Art. Suntory Museum of Art (2015).

- 1 2 Kelly, W (1990). "Japanese Farmers". The Wilson Quarterly. 14 (The Wilson Quarterly): 14(4), 34–41. JSTOR 40258510.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Nakamura, T (2014). Images of Familial Intimacy in Eastern and Western Art. Leiden: BRILL.

External links

![]() Media related to Kusumi Morikage at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kusumi Morikage at Wikimedia Commons