Kwadwo Egyir | |

|---|---|

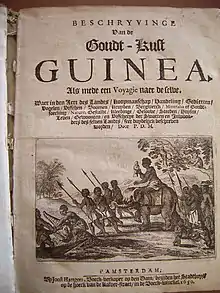

Representation of a caboceer facing a European who asks him not to kill the slaves. | |

| Born | circa 1700 |

| Died | March 24, 1779 |

| Nationality | Fante people |

| Occupation(s) | Slave trader, tribal chief |

| Employer | British Empire |

| Children | Philip Quaque |

Kwadwo Egyir, later renamed Brempong Kojo (meaning distinguished Kojo) and later Europeanized as Caboceer Cudjo (meaning chief Cudjo), was born around 1700 in Ekumfi in a Fante chiefdom on the Gold Coast, the village being located in what is now the Ekumfi district of Ghana, and died on March 24, 1779 in Cape Coast. He was a slave trader in the service of the British Gold Coast in Cape Coast.

His commercial, political and diplomatic influence made him one of the most important African figures on the Gold Coast in the 18th century. He created and structured the Oguaa State of Cape Coast, and contributed to the expansion of the British colony through diplomatic and military missions. His political influence was such that he was one of the main players in the council of Fanti chiefs and in diplomatic exchanges with the Ashanti kingdom.

He bequeathed to posterity the foundations of the future Fante confederation and contributed to the development of Cape Coast, the British colonial capital, which in fifty years became the second largest coastal city after Elmina. He created the most important Asafo order, enabling African notables to consolidate their power.

Context

In the 18th century, Cape Coast was one of the most important cities in the kingdom of Fetu (or Efutu). However, this kingdom was dismantled after a defeat in 1720 against the first Fante confederation, allowing the emergence of several small states, such as Oguaa, which appointed a Cape Coast king. This shift in authority was not a recent phenomenon, however, since it had already begun at the end of the seventeenth century, in 1694, with the first secession, during which a pro-British coalition supported several small Efutu states.

The loss of Efutu power and the dissolution of the state at the beginning of the eighteenth century created a vacuum that allowed personalities enriched by the triangular trade to increase their influence and power. Kwadwo's story is similar to that of many contemporary African merchants establishing new states.

Many caboceers[n 1] took advantage of this context to develop their economic and political influence, such as John Cabess at Komenda, John Canoe at Cape Three Points and John Currantee at Anomabu. A political vacuum also existed on the Cape Coast.[1] The British sought to strengthen their influence in African interstate politics by associating themselves with these caboceers and supporting their installation as local rulers.

Biography

Youth and oral legend

Kojo (Twi: Kwadwo) is the name given by the Fante to boys born on a Monday. Little is known about Kwadwo's birth and youth. Historians assume he was born in the last years of the 17th century or the first years of the 18th century.[2] Genealogists assume he was born in 1701, since he died at the age of 78, in 1779.[3] However, he was apparently not a native of Oguaa (Cape Coast), but of Ekumfi, in Adanse (today's Ekumfi district), and of Fante culture.[2]

This information is confirmed by oral tradition, which added that he was the son of a woman named Akuwa married to an Ekumfi-Adanse man named Kwadwo Mensa. His mother is said to have sought financial assistance from the Oguaahene Egyir Panyin (Oguaa chief of Cape Coast) in order to divorce her husband. In return, Egyir Panyin demanded her son Kwadwo, who took the name of Egyir Kwadwo.[n 2] His mother remarried the King of Efutu, making Kwadwo her son-in-law. However, the consequences of internal conflicts on the Fetu kingdom cut all ties with Cape Coast.[4] Kwadwo spoke and wrote fluent English, managed colonial affairs and mastered various local languages.

Kwadwo was given several names, nicknames and honorary titles. Before being nicknamed Caboceer Cudjo, he was called Brempong Kojo. Brempong is a Cape Coast honorific title recorded at the end of the 16th century by Pieter de Marees and confirmed in 1660 by W.J. Müller, a merchant from Brandenburg. According to Pieter de Marees, this title designated a gentleman or a great lord, while Müller translated it as "rich distinguished man". This information, combined with oral tradition and the testimony of Thomas Thompson, the first Anglican missionary to the Gold Coast, shed light on his activities before joining British officials. According to twentieth-century historian F. Crowther, Kwadwo was not actually chief of Oguaa until 1751, when his brother took his place, but held the position of dynastic chief in accordance with Efutu succession practice. The two functions were merged in the mid-19th century to put an end to succession conflicts.

Caboceer of the British

.jpg.webp)

In the 1730s or 1740s, he established himself as an influential caboceer who acted as a slave broker on behalf of the Royal African Company (RAC). He appears as early as 1728 in the account books of the Cape Coast Castle, where he was initially paid as an extraordinary messenger and translator.

He received a fortnightly salary of £7 during his first years on the job, and was able to collect a tax on the sales he concluded on behalf of the Company. For the British, he became the de facto ruler of Cape Coast, although the chief's seat was held by his brother. The power recognized by the Europeans actually came from the wealth he accumulated.[5]

Slave trader

Kwadwo's influence with the Europeans stemmed first and foremost from his ability to make a profit as a slave trader. He began as a merchant employed exclusively by the RAC, then joined the trade circuit with the African Company of Merchants and free British merchants. He then joined the Fante confederation to open up domestic trade routes to the Ashanti kingdom.[5]

Kwadwo's activities help us to understand the two distinct categories of slavery that coexisted on the Cape Coast. On the one hand, there were the traditional West African slaves known as birth slaves. These were not sold in the triangular trade and had the same rights as free individuals. The majority of Kwadwo's customers used this type of slave. The second category was that of purchased slaves from the interior of the country, also known as Duncoe or Donko. They were sold in the transatlantic slave trade.

Diplomatic missions

The British also employed him to conduct diplomatic negotiations with the Gold Coast states. In 1740, he left for Ahanta with 50 men to conduct negotiations. The allegiance of this state was fragile after the independent period under John Canoe, and represented an opportunity for the British. In 1746, he represented the British in negotiations with the Dutch at Komenda. In 1751, in a conflict pitting the Fante against the Asante, he was dispatched to Mankessim to meet with the Council of Chiefs of the Fante Confederacy and negotiate a peaceful resolution.

His diplomatic skills were widely acknowledged. During the Seven Years' War, when tensions on the Gold Coast were at their height, officer Bartels pointed out that they would have run out of provisions without Kwadwe's intervention, and his colleague Priestley added that "he was also indispensable in the Anglo-Fanti discussions held at Cape Coast Castle concerning the exclusion of all French settlements on the coast".[3]

The quality of his performance on behalf of the British can be judged from the comments justifying the award of gifts to him. His network of influence in inland territories was particularly appreciated. He received a sword "for opening the roads to Ashanti trade". He was also thanked for his military interventions, as when he went "to fight the people of Mouree [Moree]".

Political influence

Creation of the Oguaa State

.jpg.webp)

In February 1751, a petition signed by Cape Coast caboceers was addressed to the Royal African Company: "We, the principal caboceers and inhabitants of the town of Cape Coast in Africa, and also those of the kingdom of Fetua [...]". The signature read "Cudjoe Head Cabb'", meaning "Cudjoe, Chief Caboceer". Kwadwo then held a chiefly position in the town, which suggests that the creation of the Cape Coast state dates from before 1751. He established the offices of Dey and Fetera, the traditional titles of royal advisors, to underpin the structure of the new kingdom.

In his testimony, Thomas Thompson stated that in 1752 he was welcomed by the Omanhene (chief) of Cape Coast, named Amrah Coffi, who was Kwadwo's younger brother. According to Thompson, Kwadwo initially refused to occupy the siege of Cape Coast, but later traded with him, inviting him to set up a Christian school in Cape Coast and placing his son Frederick Adoy at his service as interpreter.

Although Kwadwo was not a Cape Coast Omanhene, he played an important role in the Royal Court and the Pinin Council,[n 3] leading debates with them before providing Thomas Thompson with his conclusions about what he wished to create in Cape Coast.[3]

Indeed, Kwadwo seemed interested in Thomas Thompson's missionary activities, and this connection enabled him to send three Cape Coast children to London for their education. Indeed, he convinced him to submit a request to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel to take charge of them.

In 1754, Kwadwo was crowned King of Efutu and Cape Coast in the presence of Governor Tymewell and officials from the fort. His coronation was greeted by 21 rounds of gunfire. To legitimize his accession, Kwadwo's link with the Efutu royal family was emphasized, as succession to Cape Coast was by Efutu patrilineal tradition, and Kwadwo was originally Fante.[3]

Personal armed group

In the 1750s, Thomas Thompson described the armed men who responded to Kwadwo's orders. They were known as Werempe and represented the most important 18th-century Asafo order on the Cape Coast (later renamed Ntin). They were also known as Ankobia or Kojo Nkum (Kwadwo slaves). These soldiers lived outside Cape Coast, forming the villages of Kakumdu, Mpeasem and Siwdu, also known as Werempedom. These villages now form part of Cape Coast.[3]

Broader political influence

Kwadwo's political influence extended beyond the town of Oguaa. He established links with the neighboring Cape Coast states, and in particular the Fante Bórbór, to the extent that he was appointed king of several other chiefdoms:

[...] shortly before Mr. Bell resigned, Cudjoe was made king and captain of Fantee and since then king of Ayan [Eyan], a country behind Murram and Abrah [Abora], which made him a man of far greater importance than he had ever been in all Fante country, having obliged themselves[n 4] by oath to stand by his side in all disputes whatsoever. [6]

Kwadwo played a predominant role in the Councils of Chiefs, particularly in 1752 at Efutu, and in the 1760s during conflicts with Ashanti. His influence coincided with the emergence of another coastal state, Anomabu, led by Currantee: the two men regularly joined forces to pursue a joint policy against the Dutch West India Company. Currantee's and Kwadwo's backgrounds were very similar, and they were presented by contemporaries such as Thomas Thompson as the two most important personalities on the Central Gold Coast in the early 1750s.

Family life

.jpg.webp)

Kwadwo married a woman of royal Efutu lineage named Akwaaba Abba. He thus became brother-in-law to the reigning king of Efutu, giving him additional legitimacy when the Fetu kingdom fell. Kwadwo's lineage is uncertain as, according to Fante tradition, individuals named sons and daughters were not necessarily by direct lineage, but included household slaves and their descendants.[3][n 5]

In November 1751, Kwadwo appointed his son Frederick Aday (or Adoy) as his successor on the Cape Coast Fort Council and sent him to London to studyunder a certain Temple Territory. He returned to Cape Coast in the 1770s and was appointed Fort Secretary in 1774. Another of his sons, Philip Quaque (or Kwaku Sofu), was sent to London and ordained in the Anglican Church. He entrusted him to Thomas Thompson in 1752.

When Philip Quaque returned, he settled in Cape Coast to work as a missionary. Contrary to the hopes of the United Society Partners in the Gospel, and despite his promise, Kwadwo refused to support his son in his actions and sided with the population, who wished to preserve their customs and beliefs.[5] Faced with this about-turn, Quaque expressed his displeasure in a letter:[7]

To keep me quiet, Cudjo claimed that the visionary dream he'd had some time before, when he was seriously ill, had ordered him to get rid of all these sorts of things, except for taking care of his house and family.

Death and posterity

Kwadwo died on March 24, 1779.[8] Kwesi Atta, a matrilineal descendant, ascended to the seat of dynastic chieftaincy.[9] At his funeral, a human sacrifice is said to have been performed according to Fante customs, and a succession crisis followed.[5]

Oral tradition claims that he was the founder of Cape Coast, but historical research has clarified this point.[9] However, the various states surrounding Cape Coast owe their growing political independence to Kwadwo's initiatives.[1]

For the British and the Fetu, Kwadwo's death meant the loss of a powerful figure in British Gold Coast commerce. The period that followed, between 1780 and 1803, saw a profound deterioration in Anglo-African relations, with the emergence of anti-slavery and anti-British revolts in Cape Coast.

Lineage and succession

When Kwadwo died, he left behind a complex lineage that included descendants of slave wives. They each had legitimate inheritance rights according to Fante culture. Indeed, slave wives who gave birth to a child became entitled to matrilineal succession.

- Kwadwo Egyir

- Akwaaba Abba (first wife)

- Ekua Eduabin (first daughter)

- Araba Akwaaba

- Amba Twiba

- Ajua Esson

- Ekua Eduabin (first daughter)

-

- Twiba (slave wife)

- Effua Botey (second daughter)

- Mirba

- George Sagoe

- Juliana Sagoe

- Charlotte Sagoe

- Akosua Krakaba

- Unknowns (slave wives)

- Kweku (first son)

- Abba Bessim (interregne at the death of kweku)

- Kobina Egyir (third daughter)

- Philip Quaque (second son)

- Kweku (first son)

- Akwaaba Abba (first wife)

The succession crisis that followed Kwadwo's death was rooted in confusion over his status. This confusion was perpetuated by his successors to this day. It is complex to establish with certainty which Omanhene (king according to Akan tradition) was the supreme ruler of Cape Coast during this period. However, it is known that Kwadwo was the son of a first marriage to Mame Ekua, who then married the Omanhene of Fetu and gave him a son, (and Kwadwo's brother-in-law) Egyir Enu. According to Thomas Thompson's contemporary observations, it was Egyir Enu who inherited the Cape Coast throne. However, questions of succession also included Kwadwo's connection by marriage to the daughter of the first marriage of the Omanhene of Fetu. Most of the conflict centered on patrilineal and matrilineal succession.[3]

Patrilineal and matrilineal laws of succession originated from different cultures that came together in Cape Coast in the early 18th century. The matrilineal system corresponded to the clan and dynastic systems still used by the Fante, while the patrilineal system corresponded to the Akan state system used by the Efutu. In Cape Coast, both systems were preserved to put an end to the succession conflict following Kwadwo's death. In the 19th century, this dual-throne system was dissolved.[3]

Women's elite

The role of women in Cape Coast has been particularly important from the eighteenth century to the present day, especially following the death of Kwadwo. The tradition of succession provided for two functions of local authority, each with its own mode of succession. The seat of the Oguaahene (chief of Oguaa) was inherited through patrilineal lineage, while the seat of the dynastic chief was inherited through matrilineal lineage. As a result, during Kwadwo's presence, the Cape Coast's female elite was prized by the African Company of Merchants established in 1750 by the British Parliament. Unlike the RAC, they were given the opportunity to assume official functions.[10]

The recognition of their high rank enabled them to acquire luxury goods, textiles from India and other products obtained as gifts from the African Committee. Indeed, Thomas Melvil (Governor of the Gold Coast Merchants' Committee from 1751 to 1756) demanded that gifts be provided specifically for the female elite to ensure that relations with the Cape Coast community as a whole were maintained. He requested "scarlet and blue cloths, hats adorned with gold, silver and feathers, some damasks". The most important examples of this type took place after Kwadwo's death, in order to use the positions of the female elite and win their favor.[10]

See also

Notes

- ↑ This term refers to African heads of state, city chiefs, warlords or merchant-princes.

- ↑ The oral account of Kojo's parents' marriage and divorce is described as suspicious and unlikely.

- ↑ This term refers to the "wise" elders and advisors.

- ↑ including all the Fante chiefdoms of the Fante Confederacy

- ↑ Domestic slavery on the Gold Coast was very different from slavery for sale in the Atlantic slave trade. These slaves had rights and freedoms, and were considered hereditary members of certain cultures (such as the Fante).

References

- 1 2 Shumway, Rebecca (2011). The Fante and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. University Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-391-1. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- 1 2 Crowther, Francis (February 1916). National Archives of Ghana, A.D.M. (ed.). "Case 26/16". Cape Coast Native Affaires.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Casely-Hayford, Augustus Lavinus (1992). "A Genealogical History of Cape Coast Stool Families". The School of Oriental and African Studies.

- ↑ Gocking, Roger (1981). The Historic Akoto : A Social History of Cape Coast Ghana, 1843-1948. Stanford University. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Carretta, Vincent; Reese, Ty M. (2012-06-01). The Life and Letters of Philip Quaque, the First African Anglican Missionary. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-4309-9. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- ↑ Lettre de Nassau Senior de Cape Coast Castle, December 7, 1757, P.R.O., T70/1528. Source quoted in Sanders, J.R., 1980, pp. 186-187.

- ↑ Adéẹ̀kọ́, Adélékè (2009). "Writing Africa under the Shadow of Slavery: Quaque, Wheatley, and Crowther". Research in African Literatures. 40 (4): 1–24. ISSN 0034-5210.

- ↑ Bellagamba, Alice; Greene, Sandra E.; Klein, Martin A. (2013-05-13). African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade: Volume 1, The Sources. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19470-9. Retrieved 2023-06-17.

- 1 2 Gocking, Roger (1999). Facing Two Ways: Ghana's Coastal Communities Under Colonial Rule. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-1354-5. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- 1 2 Women in Port : Gendering Communities, Economies, and Social Networks in Atlantic Port Cities, 1500-1800. BRILL. 2012-09-28. ISBN 978-90-04-23319-5. Retrieved 2023-06-17.