László Bárdossy | |

|---|---|

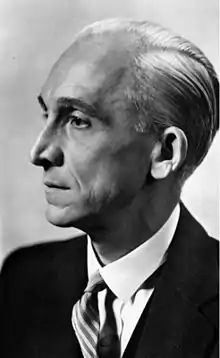

Bárdossy c. 1941 | |

| Prime Minister of Hungary | |

| In office 3 April 1941 – 7 March 1942 | |

| Regent | Miklós Horthy |

| Preceded by | Pál Teleki |

| Succeeded by | Miklós Kállay |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 December 1890 Szombathely, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 10 January 1946 (aged 55) Budapest, Hungary |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Political party | Party of Hungarian Life |

| Spouse | Marietta Braun de Belatin |

| Profession | politician, diplomat |

László Bárdossy de Bárdos (10 December 1890 – 10 January 1946) was a Hungarian diplomat and politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from April 1941 to March 1942. He was one of the chief architects of Hungary's involvement in World War II.[1]

Bárdossy was appointed Foreign Minister in January 1941 and, following Pál Teleki's suicide in April, succeeded as Prime Minister. Seeking to recover more Hungarian territories lost after the Treaty of Trianon, he pursued a strong pro-German foreign policy and Hungary supported and subsequently joined Germany's invasion of Yugoslavia. Afterwards, during his office Hungary became belligerent with Soviet Union, United Kingdom and the United States.

In March 1942, Regent Miklós Horthy dismissed Bárdossy from the post. He worked with the collaborationist governments after the German occupation of Hungary in 1944. After the end of the war, Bárdossy was found guilty of war crimes and collaborationism by a People’s Court and sentenced to death. He was executed by firing squad in January 1946.

Early life and diplomatic career

Born at Szombathely on 10 December 1890 to Jenő Bárdossy de Bárdos and Gizella Zarka de Felsőőr, Bárdossy completed his secondary education at Eperjes (in present-day Slovakia) and in Budapest. He trained as a lawyer in Budapest, Berlin and Paris, and learned German, French and English. He began his career in 1913 as an assistant clerk in the Hungarian government's Ministry of Culture and Education, by 1918 was an assistant secretary. Three years later he reached the rank of ministerial secretary, having been commissioner of education for Pest County.[2] In February 1922, he transferred to the newly established Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as deputy chief then chief of the press department.[3] In March 1930 he was appointed as a counsellor to the Hungarian legation in London,[4] latterly as chargé d'affaires.[5] From October 1934, Bárdossy was the Hungarian envoy to Romania.[4]

Foreign Minister

Hungary did not abandon the idea of reuniting the "Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen" after the Treaty of Trianon.[6] Based on this doctrine, Hungary sought the revision of the treaty, claiming territories from Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia, including regions with no significant ethnic Hungarian population, such as Croatia.[7] Between 1938 and 1940, following German–Italian mediation in the First and Second Vienna Awards, and the Hungarian invasion of Carpatho-Ukraine, Hungary enlarged its territory. It absorbed parts of southern Czechoslovakia, Carpathian Ruthenia and the northern part of Transylvania, which the Kingdom of Romania ceded. One of the ethno-cultural areas that changed hands between Romania and Hungary at this time was the Székely Land. The support that Hungary received from Germany for these border revisions meant that the relationship between the two countries became even closer. On 20 November 1940, Hungary formally joined the Axis Tripartite Pact.[8]

To simplify the planned invasion of Greece, Germany and Italy wanted to neutralize Yugoslavia.[9] For this purpose, Germany was ready to guarantee the territorial integrity of Yugoslavia.[10] News of the German offer annoyed Hungary which had already started negotiations with Yugoslavia.[10] At the initiative of Prime Minister Pál Teleki, Hungary and Yugoslavia signed a treaty of eternal friendship and non-aggression on 12 December 1940.[9] The treaty referred to the possibility of the revision of the frontier in favor of Hungary after bilateral negotiations, but Hungary explicitly abandoned her claim to Croatia.[9] Through the treaty, Hungary wanted to offset German pressure and to improve her relationship with the United Kingdom.[10]

When István Csáky died in January 1941, Bárdossy was appointed to replace him as Minister of Foreign Affairs in Teleki’s cabinet.[1] From the beginning, Bárdossy agreed with Teleki's approach to foreign affairs, which placed high priorities on Hungarian independence and staying out of World War II. However, unlike Teleki, Bárdossy believed that the war would end in German victory or a negotiated settlement. In February, the Hungarian ambassador to Great Britain advised Bárdossy that the British had broken off diplomatic relations with Romania due to the presence of German troops on its soil, and expressed disquiet over the fact that Hungary had allowed them to transit through Hungary on their way to Romania. Bárdossy replied that Hungary had allowed the transit of German troops at the request of the Romanian government. The British Foreign Office response was that Bárdossy's explanation was just a pretext, as Hungary's actions had enabled Britain's enemy to establish itself in Romania, thus creating a base for further German operations. They further explained that while they understood that Hungary and other smaller nations were in extremis, Britain was trying to extend a level of "understanding and patience" with them beyond usual diplomatic practice.[11] Bárdossy also remonstrated with the Germans regarding the guarantees they had offered the Yugoslavs, emphasising that Hungary had not given up its territorial claims. Consistent with their practice of making conflicting promises to different countries, the Germans replied that Germany recognised Hungary's revisionist claims, and that the assurances offered to the Yugoslavs would not interfere with them.[12]

On 27 February, the Yugoslav Foreign Minister, Aleksandar Cincar-Marković, arrived in Budapest to exchange the documents ratifying the Treaty of Friendship, and Teleki and Bárdossy met with him. Cincar-Marković was alarmed by the imminent Bulgarian accession to the Tripartite Pact. In early March, Teleki wrote a long memorandum regarding the expectations that the British and Americans could have of Hungary. He saw his chief responsibility as conserving Hungary's resources to the end of the war, and listed the dangers she faced, one of which was that from Yugoslavia, despite the recently signed Treaty of Friendship. He described as unreasonable the British expectation that small nations such as Hungary should oppose Germany. Despite this, he listed a number of ways in which Hungary had held firm against unreasonable German demands, including her refusal to let German troops transit through Hungary to attack Poland in 1939.[13]

On 4 March, Bárdossy gave a note to the British ambassador reiterating that the transit of German troops through Hungary at been at the request of the Romanian government. In communications with his ambassador in London he accused the British of "malice" and "considerable ignorance", and may have allowed his dislike of his ambassador to colour his assessment of the British position. On 12 March, Teleki wrote to his ambassador in London, upbraiding the British for "reproaching others for non-resistance", and claiming that the British had failed to bring the nations in the Balkans and Danube basin together, whereby they may have been able to resist the Germans. The ambassador did not receive the letter until late March, and when he went to visit Eden, the Foreign Secretary told him that he expected that Teleki would have to succumb to German pressure sooner or later, but warned that Hungary would have to face the "gravest consequences" if she allowed German troops to pass through her territory to attack a country allied with Britain, and that even worse consequences would accrue if Hungary joined in any such attack.[14]

On 25 March, the Yugoslavs acceded to the Tripartite Pact, but two days later the Yugoslav government was overthrown by a military coup. Adolf Hitler immediately ordered his generals to prepare to attack Yugoslavia, and summoned the Hungarian ambassador to Berlin, Döme Sztójay. Hitler told him that:[15]

- Germany would act to prevent any enemy bases being established against herself;

- if fighting occurred, Germany would not oppose any Hungarian revisionist claims on Yugoslav territory;

- Germany supported Croatian aspirations for autonomy; and

- Hungary might consider taking military action herself.

Hitler offered Croatia to Hungary in a message to Miklós Horthy, Regent of Hungary on 27 March.[16] Horthy was willing to join the planned invasion of Yugoslavia unconditionally, but Bárdossy and Teleki convinced him to reconsider his position. In a letter, he only promised that the Hungarian army would cooperate with the Germans and refuted Hitler's offer about Croatia.[17][16] However, Sztójay, who took the letter to Berlin on 28 March, made Hitler believe that Hungary would participate in the invasion.[17][18] Hitler stated that Germany had two friends in the Balkans, Hungary and Bulgaria, promising that their revisionist claims would be satisfied. The same day, Hungary's ministerial council met to discuss the conditions under which the Hungarian army could move into the Yugoslav territories formerly part of Hungary. They agreed this could occur if one of the following conditions were met:[17][19]

- if Yugoslavia ceased to exist as a state, i.e. if Croatia was to proclaim its independence;

- if the security of the Hungarian minority in Yugoslavia was endangered; or

- if a vacuum was created by German military action in areas occupied by the Hungarian minority.

The following day, the Hungarian ambassador in London asked for clarification as to whether, in case of a German attack on Yugoslavia, Hungary would uphold the Treaty of Eternal Friendship. Bárdossy wrote back, copying the same message to his ambassador to the United States, stating that there was a very real likelihood that Yugoslavia would disintegrate, and that secession of Croatia and Slovenia would create a situation where Hungary would have to act to protect the Hungarian minority in Vojvodina.[20] Acting under the impression that Horthy's letter had approved such action, Chief of the Hungarian General Staff, General Henrik Werth and his chief of operations, Colonel Dezső László were negotiating with German General Friedrich Paulus, chief of operations of the German Army. The Hungarian high command believed that the Germans needed evidence of Hungary's friendship, and, contradicting the conditions already set, agreed that Hungarian forces could operate outside former Hungarian territories within Yugoslavia.[21]

Horthy called a meeting of the Supreme Defence Council on 1 April. Bárdossy advocated the position that the Hungarian Army should only move into areas of Yugoslavia occupied by the Hungarian minority under the conditions agreed to on 28 March. He said that Germany should be told this, and that any Hungarian action would be independent of the Germans. Minister of the Interior Ferenc Keresztes-Fischer and others agreed, but Werth, and Minister of Defence Károly Bartha pushed for immediate military action on the basis of the letters exchanged between Horthy and Hitler. Teleki then spoke, reminding those present of the enormous resources of Britain and the United States, and saying that Hungary should not take action they would consider unacceptable. He agreed with Bárdossy that it would be acceptable to enter former Hungarian territories in Yugoslavia only after Yugoslavia had collapsed. In the end, the Council adopted resolutions proposed by Teleki and Bárdossy, which modified the conditions agreed to on 28 March. They were that:[22][19]

- the Hungarian Army would not pass beyond the line formed by the Danube and Drava;

- preparations were to be made to mobilise, but with Horthy making the final decision; and

- all Hungarian units were to be under Horthy's ultimate command, and were not to be subordinated to German command.

On 2 April, the British warned the Hungarian ambassador that if Hungary allowed the transit of the Germans through her territory to attack Yugoslavia, Britain would break off diplomatic relations. They also cautioned Hungary that if she joined the attack on Yugoslavia under any pretext, she must expect Britain and her allies to declare war, and, if that occurred, could expect to be treated appropriately should the Allies be victorious. The British observed that Hungary had renounced its claims on Yugoslav territory when it signed the Treaty of Friendship, and that any attack on Yugoslavia would be a flagrant breach of the treaty. These warnings were passed on to the Hungarian government by telegram.[23]

When Hitler requested clearance to launch one of his armoured thrusts against Yugoslavia using Hungarian territory, Teleki was unable to dissuade the Regent. The Tripartite Act allowed the German Army to be deployed in Hungary's territory.[24]

Concluding that Hungary had disgraced itself irrevocably by siding with the Germans against the Yugoslavs, Teleki shot himself on 3 April.[25][26] In his suicide note to Horthy, he wrote,

We have become breakers of our word—out of cowardice—in defiance of the Treaty of Eternal Friendship... we have placed ourselves at the side of scoundrels... We shall be robbers of corpses! the most abominable nation.[27]

Horthy informed Hitler that evening that Hungary would abide by the Treaty of Eternal Friendship with Yugoslavia, though it would likely cease to apply should Croatia secede and Yugoslavia cease to exist.[28] He then ordered the mobilisation of two army corps.[29]

Prime Minister

Invasion of Yugoslavia

When Teleki committed suicide, Horthy first offered the prime ministership to Keresztes-Fischer, but when he refused it, Bárdossy was appointed.[30] As prime minister, Bárdossy (who also retained the portfolio of foreign minister) pursued a strong pro-German foreign policy, reasoning that an alliance with the Nazis would allow Hungary to retrieve land that had been taken from it as a result of the Treaty of Trianon. On 6 April, Germany invaded Yugoslavia. Bárdossy and Horthy had agreed to allow the Germans to launch part of their invasion from Hungarian territory.[19]

On 7 April, Yugoslav bombers of British-design launched raids on Hungarian airfields and railway stations. One of the targets was an airfield near Szeged, but when the Yugoslav aircraft found it empty, they dropped their bombs on the railway network. Another formation attacked airfields used by the Hungarian Air Force around Pécs. Both bomber formations were almost completely destroyed by German fighter aircraft and Hungarian anti-aircraft fire.[31] A rumour spread that British aircraft had been involved in these raids, but this was a false report, probably generated by those in the Hungarian military who wanted Hungary to join in the German campaign. Bárdossy lodged a strong protest with the British regarding the supposed British attack.[32][lower-alpha 1]

The Axis puppet Independent State of Croatia was proclaimed on 10 April.[19][34] Later that day, Horthy issued a directive to the Hungarian Army ordering it to intervene in Yugoslavia to safeguard the Hungarian minority.[35] The Hungarian government used the pretext that Yugoslavia had ceased to exist,[36][37][38] and therefore make the claim that Hungary was not invading it — and on that basis the Hungarian Army crossed the frontier on 11 April.[39] On 13 April, the 1st and 2nd Hungarian Motorized Brigades occupied Novi Sad, then pushed south across the Danube into Syrmia capturing the Croatian towns of Vinkovci and Vukovar on 18 April. These brigades then drove southeast to capture the Serbian town of Valjevo a day later. Other Hungarian forces occupied the regions of Prekmurje and Međimurje.[40] The British considered that Bárdossy's claim was a ludicrous attempt to justify the Hungarian invasion of Yugoslavia, with Eden stating that it would remain an "everlasting shame upon the reputation of Hungary" that she had attacked Yugoslavia a few months after concluding a pact of friendship with her. Even so, Churchill did not declare war on Hungary for some months, despite Eden and Stalin urging him to do so.[41] The Hungarian attack on Yugoslavia has been described by the Hungarian historians Miklós Incze and György Ránki as "the most shameful act of wartime Hungarian policy".[42]

Afterwards, Hungarian troops occupied parts of Yugoslav territory that had formerly belonged to Hungary prior to the Treaty of Trianon, and these lands were subsequently annexed by Hungary.

War with the Soviet Union

On 22 June 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union. Four days later, the Hungarian city of Kassa (present-day Košice in Slovakia) was bombed by three unidentified aircraft. One bomb failed to explode and was found to be of Soviet origin. The Hungarian military concluded that the Soviet Union was responsible (this was denied, and the question of responsibility has never been satisfactorily resolved). When Bartha and Werth became aware of the bombing, they went to Horthy who ordered retaliatory measures without consulting Bárdossy. However, Bárdossy believed that Horthy wanted war with the Soviet Union, so he hurriedly assembled the Council of Ministers. In summing up the meeting, Bárdossy said that it was agreed that reprisals were necessary, and, with the exception of Keresztes-Fischer, that they agreed that Hungary was now at war with the Soviet Union. The following day, Bárdossy stood up in Parliament and declared the attack had been made by the Soviet Union, and that the government had decided that a state of war existed between Hungary and the Soviet Union. Horthy subsequently claimed that Bárdossy had presented him with a fait accompli.[43]

In so doing, he violated Hungary’s constitution, which required the prime minister to receive the consent of Parliament before declaring war.

War with Great Britain and the United States

In late November 1941, Britain delivered an ultimatum to Hungary, stating that if it did not withdraw its forces from the Soviet Union by 5 December, Britain would declare war. Bárdossy took no action to comply, so a state of war came into effect at midnight on 6 December. The following day, the Japanese launched their attack on Pearl Harbor. Four days later, Germany declared war on the United States. Bárdossy was reluctant to follow suit, despite German expectations that Hungary would do so as a member of the Tripartite Pact. In an attempt to avoid a declaration of war, the Council of Ministers proposed breaking off diplomatic relations and expressing solidarity with the Axis powers. This did not satisfy the Germans or Italians, who made their expectations clear. Finally, realising that he would be unable to get approval from Parliament or Horthy for a declaration of war, Bárdossy announced a state of war with the United States at a parliamentary foreign affairs committee on 15 December.[44]

Domestic policies

On matters of domestic policy, Bárdossy proved to be an advocate of radical right-wing politics. An anti-Semite, Bárdossy enacted the Third Jewish Law in August 1941, which severely limited Jewish economic and employment opportunities and prohibited Jews from marrying or having sexual intercourse with non-Jews. Bárdossy also approved the policy of deporting non-Hungarians from the territory seized from Yugoslavia, and authorized the slaughter of thousands of Jews in Újvidék.

Later life and execution

On 7 March 1942, Horthy forced Bárdossy's resignation in favour of the more moderate Miklós Kállay. Exactly why Horthy decided to remove Bárdossy is unclear, but some possible reasons include Bárdossy’s unwillingness to stand up to Germany, his compliancy to Hungary’s far-right and growing increasing Hungarian troop levels and casualties in the Soviet Union. Perhaps the primary reason that Horthy dismissed Bárdossy, however, was that Bárdossy successfully opposed a plan by Horthy that would have elevated his son, Miklós Jr, to the regency after Miklós Horthy’s death. After resigning as prime minister, Bárdossy became chairman of the Fascist United Christian National League in 1943. After the German occupation of Hungary in 1944, Bárdossy and his followers collaborated with Prime Minister Döme Sztójay. Later on, they collaborated with Ferenc Szálasi's Arrow Cross Party. He fled from Szombathely due to Soviet advance in Hungary and moved initially to Bavaria, then to Innsbruck. He obtained entry visa to Switzerland on 24 April 1945 and lived briefly in a refugee camp. However, the Swiss government deported him back to Germany on 4 May 1945. He was immediately arrested by Americans.

After World War II ended, Bárdossy was extradited to Hungary on 3 October 1945. He was tried by an extra-judicial People’s Court between 19 October 1945 and 3 November 1945. He was found guilty of war crimes and collaboration with the Nazis, sentenced to death, and executed by firing squad in Budapest on 10 January 1946.

Appraisal

Bárdossy took over his roles as foreign minister and prime minister at a critical moment in Hungary's history. Despite the importance of Britain, he did not really understand the British, and was "rather contemptuous, dismissive and at times condescending" towards them. His poor relationship with his ambassador to London probably contributed to this. He maintained Teleki's foreign policy priorities without fully identifying with them. His appointment as prime minister was much more acceptable to the Germans than Keresztes-Fischer. Bárdossy was a contradictory character who did not always comprehend the geo-political situation Hungary found herself in, especially vis-à-vis Britain. His accusation that the British had bombed Hungary on 7 April 1941 was one of several significant political blunders, as was the announcement of a state of war with the Soviet Union in June 1941, and with the United States in December 1941.[45]

Notes

Footnotes

- 1 2 Frucht 2000, p. 56.

- ↑ Pritz 2004, p. 5.

- ↑ Pritz 2004, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 Pritz 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ Bán 2004, p. 19.

- ↑ Lemkin 2008, pp. 144–146.

- ↑ Lemkin 2008, pp. 144–146, 261.

- ↑ Pogany 1997, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Frank 2001, p. 171.

- 1 2 3 Cornelius 2011, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Bán 2004, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Cornelius 2011, p. 139.

- ↑ Bán 2004, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Bán 2004, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Bán 2004, pp. 118–119.

- 1 2 War and Revolution in Yugoslavia: 1941 - 1945 - Jozo Tomasevich p. 48.

- 1 2 3 Bán 2004, p. 119.

- ↑ Cornelius 2011, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Babucs, Zoltán. "Virágeső helyett golyózápor hullott".

Ezen levélváltás épp folyamatban volt, amikor a minisztertanács döntött arról, hogy a honvédség csak a Duna-Tisza közén kezdhet hadműveleteket, és nem lépheti át a történelmi magyar határt." - " Így, ha Jugoszlávia, mint állam felbomlik, ha a hadműveletek következében hatalmi vákuum keletkezik térségben, illetve ha a magyar kisebbséget bármilyen veszély fenyegetné." - "A Jugoszlávia ellen 1941. április 6-án megindított német támadás – a másnap Pécs, Siklós és Szeged ellen intézett jugoszláv bombatámadások – és Horvátország függetlenségének április 10-én történt proklamálását követően, a széthullott Jugoszláviában élő magyar nemzetiség védelmében lépett fel a magyar politikai és katonai vezetés.

- ↑ Bán 2004, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Cornelius 2011, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Bán 2004, p. 120.

- ↑ Bán 2004, p. 121.

- ↑ Kádár, Gyula; István, Szilágyi. "75 éve foglalták vissza a honvédek Délvidéket". Kádár Gyula: A Ludovikától Sopronkőhidáig. Budapest, 1978 - Szilágyi István: Egy magyar katona feljegyzései a bevonulásról. In: Vincze Gábor (szerk.): Visszatér a Délvidék. Budapest, 2011.

- ↑ Eby 2007, p. 15.

- ↑ Coppa 2006, p. 115.

- ↑ Cornelius 2011, p. 143.

- ↑ Klajn 2007, p. 106.

- ↑ Cornelius 2011, p. 144.

- ↑ Bán 2004, p. 143.

- ↑ Shores, Cull & Malizia 1987, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Bán 2004, p. 124.

- ↑ "Az állomásfőnök díványain pattogott a bomba".

Aznap két jugoszláv kötelék repült be magyar területre, az egyik célpontja Pécs, a másiké Szeged volt. A szegediek elsősorban a vasúti állomást és a vasúti hidat keresték. Az első támadásnál a szürke testű jugoszláv gépek 6 bombát dobtak le Szegedre, a vasútállomás környékére.

- ↑ "Az állomásfőnök díványain pattogott a bomba".

Aznap két jugoszláv kötelék repült be magyar területre, az egyik célpontja Pécs, a másiké Szeged volt. A szegediek elsősorban a vasúti állomást és a vasúti hidat keresték. Az első támadásnál a szürke testű jugoszláv gépek 6 bombát dobtak le Szegedre, a vasútállomás környékére.

- ↑ Bán 2004, p. 125.

- ↑ "Magyar tragédia a Délvidéken | Kronológia".

- ↑ Lambert, Sean (15 May 2015). "The Horthy Era (1920–1944)".

The government of newly appointed Prime Minister László Bárdossy claimed that the invasion did not violate the Hungarian-Yugoslav Eternal Friendship Treaty because the Kingdom of Yugoslavia had ceased to exist with the proclamation on April 10 of the pro-German Independent State of Croatia.

- ↑ "Hungary - History".

- ↑ Tarján, M. Tamás. "A Délvidék visszafoglalása". www.rubiconline.hu.

1941. április 11-én lépték át a Magyar Királyi Honvédség csapatai a volt magyar–jugoszláv határt, hogy fennhatóságuk alá vonják Bácskát, a Muraközt és a Baranya-háromszöget.

- ↑ Thomas & Szabo 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Bán 2004, pp. 126–128.

- ↑ Incze & Ránki 1958, p. 426.

- ↑ Cornelius 2011, pp. 148–152.

- ↑ Cornelius 2011, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Bán 2004, pp. 143–148.

References

In English

Books

- Bán, András (2004). Hungarian-British Diplomacy, 1938-1941: The Attempt to Maintain Relations. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7146-8565-6. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- Botond, Clementis-Záhony (1988). "Bárdossy Reconsidered: Hungary's Entrance into World War II". Triumph in Adversity. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Coppa, Frank J. (2006). Encyclopedia of Modern Dictators: From Napoleon to the Present. New York, New York: Peter Lang Press. ISBN 978-0-8204-5010-0.

- Cornelius, Deborah S. (2011). Hungary in World War II: Caught in the Cauldron. Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-3343-4.

- István Deák; Jan T. Gross; Tony Judt, eds. (2009). The Politics of Retribution in Europe: World War II and Its Aftermath. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3205-7.

- Eby, Cecil D. (2007). Hungary at War: Civilians and Soldiers in World War II. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-03244-3.

- Frank, Tibor (2001). "Treaty Revision and Doublespeak: Hungarian Neutrality, 1939–1941". In Wylie, Neville (ed.). European Neutrals and Non-Belligerents During the Second World War. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire: Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–191. ISBN 978-0-521-64358-0.

- Frucht, Richard C. (2000). Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism. Garland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8153-0092-2.

- Handler, Andrew (1996). A Man for All Connections: Raoul Wallenberg and the Hungarian State Apparatus, 1944-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-95214-3.

- Klajn, Lajčo (2007). The Past in Present Times: The Yugoslav Saga. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-3647-6.

- Lemkin, Raphael (2008). Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Clark, New Jersey: The Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.

- Nandor F. Dreisziger: Was László Bárdossy a War Criminal? Further Reflections, In: Hungary in the Age of Total War 1938–1948 (Bradenton: East European Monographs, distr. through Columbia University Press, 1998) pp. 311–320.

- Pogany, Istvan S. (1997). Righting Wrongs in Eastern Europe. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press ND. ISBN 978-0-7190-3042-0.

- Pritz, Pál (2004). The War Crimes Trial of Hungarian Prime Minister László Bárdossy. Social Science Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-549-2.

- Shores, Christopher F.; Cull, Brian; Malizia, Nicola (1987). Air War for Yugoslavia, Greece, and Crete, 1940–41. London, England: Grub Street. ISBN 978-0-948817-07-6.

- Thomas, Nigel; Szabo, Laszlo (2008). The Royal Hungarian Army in World War II. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-324-7.

Journals

- Nandor F. Dreisziger: "A Dove? A Hawk? Perhaps a Sparrow: Bárdossy Defends his Wartime Record before the Americans, July 1945," in Hungary Fifty Years Ago, N.F. Dreisziger ed. (Toronto and Budapest: special issue of the Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XXII, Nos. 1–2, 1995), pp. 71–90.

- Nandor F. Dreisziger: "Prime Minister László Bárdossy was Executed 50 Years Ago as a 'War Criminal'," in Tárogató: the Journal of the Hungarian Cultural Society of Vancouver, Vol. XXIII, no. 11 (November 1996), pp. 56–57.

- Incze, M.; Ránki, Gy. (1958). "October Fifteenth: A History of Modern Hungary, 1929—1945 by C. A. Macartney". Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Institute of History, Research Centre for the Humanities, Hungarian Academy of Sciences. 5 (3/4): 419–428. JSTOR 42554607.

In Hungarian

- Bárdossy László: Magyar politika a mohácsi vész után. Budapest, 1943.

- A Bárdossy-per / a Magyar Országos Tudósitó és a Magyar Távirati Iroda hivatalos kiadásaiból szerk. Ábrahám Ferenc, Kussinszky Endre, Budapest, 1945.

- Bárdossy László a Népbíróság elõtt, [szerk: Pritz Pál] Bp. : Maecenas, 1991. (dokumentumok)

- Bûnös volt-e Bárdossy László [ed.Jaszovszky László] Budapest, Püski, 1996. (az elsőfokú tárgyalás jegyzőkönyve)

- Czettler Antal: A mi kis élethalál kérdéseink. A magyar külpolitika a hadbalépéstől a német megszállásig. Bp., 2000, Magvető.

- PERJÉS Géza: Bárdossy László és pere. Hadtörténelmi közlemények. 113. 2000. 4. 771–840.

- Pritz Pál: A Bárdossy-per, Bp. : Kossuth, [2001].

- JASZOVSZKY László: Észrevételek Perjés Géza "Bárdossy László és pere" című tanulmányához. Hadtörténelmi közlemények. 114. 2001. 4. 711–725.

- CLEMENTIS-ZÁHONY Botond: Hozzászólás Perjés Géza Bárdossy-tanulmányához. = Hadtörténelmi közlemények. 114. 2001. 4. 726–734.

- PRITZ Pál: Válasz Perjés Gézának. Hadtörténelmi közlemények. 114. 2001. 4.

- PERJÉS Géza: Viszontválasz Pritz Pálnak. Hadtörténelmi közlemények. 114. 2001. 4.

- Bokor Imre: Gróf Teleki Pálról és Bárdossy Lászlóról, Budapest, Szenci M. Társ., 2002.

- Szerencsés Károly: "Az ítélet: halál" magyar miniszterelnökök a bíróság elõtt : Batthyány Lajos, Bárdossy László, Imrédy Béla, Szálasi Ferenc, Sztójay Döme, Nagy Imre, Bp. : Kairosz, [2002]

External links

- The Fateful Year: 1942 in the Reports of Hungarian Diplomats

- The war crimes trial of Hungarian Prime Minister László Bárdossy

- Newspaper clippings about László Bárdossy in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

.svg.png.webp)