- Polarizing filter film with a vertical axis to polarize light as it enters.

- Glass substrate with ITO electrodes. The shapes of these electrodes will determine the shapes that will appear when the LCD is switched ON. Vertical ridges etched on the surface are smooth.

- Twisted nematic liquid crystal.

- Glass substrate with common electrode film (ITO) with horizontal ridges to line up with the horizontal filter.

- Polarizing filter film with a horizontal axis to block/pass light.

- Reflective surface to send light back to viewer. (In a backlit LCD, this layer is replaced or complemented with a light source.)

A liquid-crystal display (LCD) is a flat-panel display or other electronically modulated optical device that uses the light-modulating properties of liquid crystals combined with polarizers. Liquid crystals do not emit light directly[1] but instead use a backlight or reflector to produce images in color or monochrome.[2] LCDs are available to display arbitrary images (as in a general-purpose computer display) or fixed images with low information content, which can be displayed or hidden: preset words, digits, and seven-segment displays (as in a digital clock) are all examples of devices with these displays. They use the same basic technology, except that arbitrary images are made from a matrix of small pixels, while other displays have larger elements. LCDs can either be normally on (positive) or off (negative), depending on the polarizer arrangement. For example, a character positive LCD with a backlight will have black lettering on a background that is the color of the backlight, and a character negative LCD will have a black background with the letters being of the same color as the backlight. Optical filters are added to white on blue LCDs to give them their characteristic appearance.

LCDs are used in a wide range of applications, including LCD televisions, computer monitors, instrument panels, aircraft cockpit displays, and indoor and outdoor signage. Small LCD screens are common in LCD projectors and portable consumer devices such as digital cameras, watches, calculators, and mobile telephones, including smartphones. LCD screens have replaced heavy, bulky and less energy-efficient cathode-ray tube (CRT) displays in nearly all applications. The phosphors used in CRTs make them vulnerable to image burn-in when a static image is displayed on a screen for a long time, e.g., the table frame for an airline flight schedule on an indoor sign. LCDs do not have this weakness, but are still susceptible to image persistence.[3]

General characteristics

Each pixel of an LCD typically consists of a layer of molecules aligned between two transparent electrodes, often made of indium tin oxide (ITO) and two polarizing filters (parallel and perpendicular polarizers), the axes of transmission of which are (in most of the cases) perpendicular to each other. Without the liquid crystal between the polarizing filters, light passing through the first filter would be blocked by the second (crossed) polarizer. Before an electric field is applied, the orientation of the liquid-crystal molecules is determined by the alignment at the surfaces of electrodes. In a twisted nematic (TN) device, the surface alignment directions at the two electrodes are perpendicular to each other, and so the molecules arrange themselves in a helical structure, or twist. This induces the rotation of the polarization of the incident light, and the device appears gray. If the applied voltage is large enough, the liquid crystal molecules in the center of the layer are almost completely untwisted and the polarization of the incident light is not rotated as it passes through the liquid crystal layer. This light will then be mainly polarized perpendicular to the second filter, and thus be blocked and the pixel will appear black. By controlling the voltage applied across the liquid crystal layer in each pixel, light can be allowed to pass through in varying amounts thus constituting different levels of gray.

The chemical formula of the liquid crystals used in LCDs may vary. Formulas may be patented.[4] An example is a mixture of 2-(4-alkoxyphenyl)-5-alkylpyrimidine with cyanobiphenyl, patented by Merck and Sharp Corporation. The patent that covered that specific mixture expired.[5]

Most color LCD systems use the same technique, with color filters used to generate red, green, and blue subpixels. The LCD color filters are made with a photolithography process on large glass sheets that are later glued with other glass sheets containing a thin-film transistor (TFT) array, spacers and liquid crystal, creating several color LCDs that are then cut from one another and laminated with polarizer sheets. Red, green, blue and black photoresists (resists) are used. All resists contain a finely ground powdered pigment, with particles being just 40 nanometers across. The black resist is the first to be applied; this will create a black grid (known in the industry as a black matrix) that will separate red, green and blue subpixels from one another, increasing contrast ratios and preventing light from leaking from one subpixel onto other surrounding subpixels.[6] After the black resist has been dried in an oven and exposed to UV light through a photomask, the unexposed areas are washed away, creating a black grid. Then the same process is repeated with the remaining resists. This fills the holes in the black grid with their corresponding colored resists.[7][8][9] Another color-generation method used in early color PDAs and some calculators was done by varying the voltage in a Super-twisted nematic LCD, where the variable twist between tighter-spaced plates causes a varying double refraction birefringence, thus changing the hue.[10] They were typically restricted to 3 colors per pixel: orange, green, and blue.[11]

The optical effect of a TN device in the voltage-on state is far less dependent on variations in the device thickness than that in the voltage-off state. Because of this, TN displays with low information content and no backlighting are usually operated between crossed polarizers such that they appear bright with no voltage (the eye is much more sensitive to variations in the dark state than the bright state). As most of 2010-era LCDs are used in television sets, monitors and smartphones, they have high-resolution matrix arrays of pixels to display arbitrary images using backlighting with a dark background. When no image is displayed, different arrangements are used. For this purpose, TN LCDs are operated between parallel polarizers, whereas IPS LCDs feature crossed polarizers. In many applications IPS LCDs have replaced TN LCDs, particularly in smartphones. Both the liquid crystal material and the alignment layer material contain ionic compounds. If an electric field of one particular polarity is applied for a long period of time, this ionic material is attracted to the surfaces and degrades the device performance. This is avoided either by applying an alternating current or by reversing the polarity of the electric field as the device is addressed (the response of the liquid crystal layer is identical, regardless of the polarity of the applied field).

Displays for a small number of individual digits or fixed symbols (as in digital watches and pocket calculators) can be implemented with independent electrodes for each segment.[12] In contrast, full alphanumeric or variable graphics displays are usually implemented with pixels arranged as a matrix consisting of electrically connected rows on one side of the LC layer and columns on the other side, which makes it possible to address each pixel at the intersections. The general method of matrix addressing consists of sequentially addressing one side of the matrix, for example by selecting the rows one-by-one and applying the picture information on the other side at the columns row-by-row. For details on the various matrix addressing schemes see passive-matrix and active-matrix addressed LCDs.

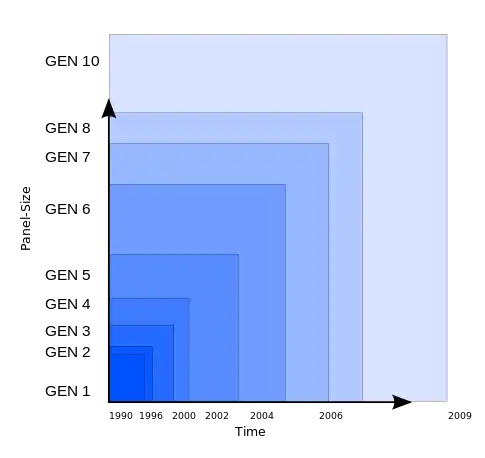

LCDs are manufactured in cleanrooms borrowing techniques from semiconductor manufacturing and using large sheets of glass whose size has increased over time. Several displays are manufactured at the same time, and then cut from the sheet of glass, also known as the mother glass or LCD glass substrate. The increase in size allows more displays or larger displays to be made, just like with increasing wafer sizes in semiconductor manufacturing. The glass sizes are as follows:

| Generation | Length (mm) | Height (mm) | Year of introduction | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEN 1 | 200–300 | 200–400 | 1990 | [13][14] |

| GEN 2 | 370 | 470 | ||

| GEN 3 | 550 | 650 | 1996–1998 | [15] |

| GEN 3.5 | 600 | 720 | 1996 | [14] |

| GEN 4 | 680 | 880 | 2000–2002 | [14][15] |

| GEN 4.5 | 730 | 920 | 2000–2004 | [16] |

| GEN 5 | 1100 | 1250–1300 | 2002–2004 | [14][15] |

| GEN 5.5 | 1300 | 1500 | ||

| GEN 6 | 1500 | 1800–1850 | 2002–2004 | [14][15] |

| GEN 7 | 1870 | 2200 | 2003 | [17][18] |

| GEN 7.5 | 1950 | 2250 | [14] | |

| GEN 8 | 2160 | 2460 | [18] | |

| GEN 8.5 | 2200 | 2500 | 2007–2016 | [19] |

| GEN 8.6 | 2250 | 2600 | 2016 | [19] |

| GEN 10 | 2880 | 3130 | 2009 | [20] |

| GEN 10.5 (also known as GEN 11) | 2940 | 3370 | 2018[21] | [22] |

Until Gen 8, manufacturers would not agree on a single mother glass size and as a result, different manufacturers would use slightly different glass sizes for the same generation. Some manufacturers have adopted Gen 8.6 mother glass sheets which are only slightly larger than Gen 8.5, allowing for more 50- and 58-inch LCDs to be made per mother glass, specially 58-inch LCDs, in which case 6 can be produced on a Gen 8.6 mother glass vs only 3 on a Gen 8.5 mother glass, significantly reducing waste.[19] The thickness of the mother glass also increases with each generation, so larger mother glass sizes are better suited for larger displays. An LCD module (LCM) is a ready-to-use LCD with a backlight. Thus, a factory that makes LCD modules does not necessarily make LCDs, it may only assemble them into the modules. LCD glass substrates are made by companies such as AGC Inc., Corning Inc., and Nippon Electric Glass.

History

The origins and the complex history of liquid-crystal displays from the perspective of an insider during the early days were described by Joseph A. Castellano in Liquid Gold: The Story of Liquid Crystal Displays and the Creation of an Industry.[23] Another report on the origins and history of LCD from a different perspective until 1991 has been published by Hiroshi Kawamoto, available at the IEEE History Center.[24] A description of Swiss contributions to LCD developments, written by Peter J. Wild, can be found at the Engineering and Technology History Wiki.[25]

Background

In 1888,[26] Friedrich Reinitzer (1858–1927) discovered the liquid crystalline nature of cholesterol extracted from carrots (that is, two melting points and generation of colors) and published his findings.[27] In 1904, Otto Lehmann published his work "Flüssige Kristalle" (Liquid Crystals). In 1911, Charles Mauguin first experimented with liquid crystals confined between plates in thin layers.

In 1922, Georges Friedel described the structure and properties of liquid crystals and classified them in three types (nematics, smectics and cholesterics). In 1927, Vsevolod Frederiks devised the electrically switched light valve, called the Fréedericksz transition, the essential effect of all LCD technology. In 1936, the Marconi Wireless Telegraph company patented the first practical application of the technology, "The Liquid Crystal Light Valve". In 1962, the first major English language publication Molecular Structure and Properties of Liquid Crystals was published by Dr. George W. Gray.[28] In 1962, Richard Williams of RCA found that liquid crystals had some interesting electro-optic characteristics and he realized an electro-optical effect by generating stripe patterns in a thin layer of liquid crystal material by the application of a voltage. This effect is based on an electro-hydrodynamic instability forming what are now called "Williams domains" inside the liquid crystal.[29]

Building on early MOSFETs, Paul K. Weimer at RCA developed the thin-film transistor (TFT) in 1962.[30] It was a type of MOSFET distinct from the standard bulk MOSFET.[31]

1960s

In 1964, George H. Heilmeier, then working at the RCA laboratories on the effect discovered by Williams achieved the switching of colors by field-induced realignment of dichroic dyes in a homeotropically oriented liquid crystal. Practical problems with this new electro-optical effect made Heilmeier continue to work on scattering effects in liquid crystals and finally the achievement of the first operational liquid-crystal display based on what he called the dynamic scattering mode (DSM). Application of a voltage to a DSM display switches the initially clear transparent liquid crystal layer into a milky turbid state. DSM displays could be operated in transmissive and in reflective mode but they required a considerable current to flow for their operation.[32][33][34][35] George H. Heilmeier was inducted in the National Inventors Hall of Fame[36] and credited with the invention of LCDs. Heilmeier's work is an IEEE Milestone.[37]

In the late 1960s, pioneering work on liquid crystals was undertaken by the UK's Royal Radar Establishment at Malvern, England. The team at RRE supported ongoing work by George William Gray and his team at the University of Hull who ultimately discovered the cyanobiphenyl liquid crystals, which had correct stability and temperature properties for application in LCDs.

The idea of a TFT-based liquid-crystal display (LCD) was conceived by Bernard Lechner of RCA Laboratories in 1968.[38] Lechner, F.J. Marlowe, E.O. Nester and J. Tults demonstrated the concept in 1968 with an 18x2 matrix dynamic scattering mode (DSM) LCD that used standard discrete MOSFETs.[39]

1970s

On December 4, 1970, the twisted nematic field effect (TN) in liquid crystals was filed for patent by Hoffmann-LaRoche in Switzerland, (Swiss patent No. 532 261) with Wolfgang Helfrich and Martin Schadt (then working for the Central Research Laboratories) listed as inventors.[32] Hoffmann-La Roche licensed the invention to Swiss manufacturer Brown, Boveri & Cie, its joint venture partner at that time, which produced TN displays for wristwatches and other applications during the 1970s for the international markets including the Japanese electronics industry, which soon produced the first digital quartz wristwatches with TN-LCDs and numerous other products. James Fergason, while working with Sardari Arora and Alfred Saupe at Kent State University Liquid Crystal Institute, filed an identical patent in the United States on April 22, 1971.[40] In 1971, the company of Fergason, ILIXCO (now LXD Incorporated), produced LCDs based on the TN-effect, which soon superseded the poor-quality DSM types due to improvements of lower operating voltages and lower power consumption. Tetsuro Hama and Izuhiko Nishimura of Seiko received a US patent dated February 1971, for an electronic wristwatch incorporating a TN-LCD.[41] In 1972, the first wristwatch with TN-LCD was launched on the market: The Gruen Teletime which was a four digit display watch.

In 1972, the concept of the active-matrix thin-film transistor (TFT) liquid-crystal display panel was prototyped in the United States by T. Peter Brody's team at Westinghouse, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[42] In 1973, Brody, J. A. Asars and G. D. Dixon at Westinghouse Research Laboratories demonstrated the first thin-film-transistor liquid-crystal display (TFT LCD).[43][44] As of 2013, all modern high-resolution and high-quality electronic visual display devices use TFT-based active matrix displays.[45] Brody and Fang-Chen Luo demonstrated the first flat active-matrix liquid-crystal display (AM LCD) in 1974, and then Brody coined the term "active matrix" in 1975.[38]

In 1972 North American Rockwell Microelectronics Corp introduced the use of DSM LCDs for calculators for marketing by Lloyds Electronics Inc, though these required an internal light source for illumination.[46] Sharp Corporation followed with DSM LCDs for pocket-sized calculators in 1973[47] and then mass-produced TN LCDs for watches in 1975.[48] Other Japanese companies soon took a leading position in the wristwatch market, like Seiko and its first 6-digit TN-LCD quartz wristwatch, and Casio's 'Casiotron'. Color LCDs based on Guest-Host interaction were invented by a team at RCA in 1968.[49] A particular type of such a color LCD was developed by Japan's Sharp Corporation in the 1970s, receiving patents for their inventions, such as a patent by Shinji Kato and Takaaki Miyazaki in May 1975,[50] and then improved by Fumiaki Funada and Masataka Matsuura in December 1975.[51] TFT LCDs similar to the prototypes developed by a Westinghouse team in 1972 were patented in 1976 by a team at Sharp consisting of Fumiaki Funada, Masataka Matsuura, and Tomio Wada,[52] then improved in 1977 by a Sharp team consisting of Kohei Kishi, Hirosaku Nonomura, Keiichiro Shimizu, and Tomio Wada.[53] However, these TFT-LCDs were not yet ready for use in products, as problems with the materials for the TFTs were not yet solved.

1980s

In 1983, researchers at Brown, Boveri & Cie (BBC) Research Center, Switzerland, invented the super-twisted nematic (STN) structure for passive matrix-addressed LCDs. H. Amstutz et al. were listed as inventors in the corresponding patent applications filed in Switzerland on July 7, 1983, and October 28, 1983. Patents were granted in Switzerland CH 665491, Europe EP 0131216,[54] U.S. Patent 4,634,229 and many more countries. In 1980, Brown Boveri started a 50/50 joint venture with the Dutch Philips company, called Videlec.[55] Philips had the required know-how to design and build integrated circuits for the control of large LCD panels. In addition, Philips had better access to markets for electronic components and intended to use LCDs in new product generations of hi-fi, video equipment and telephones. In 1984, Philips researchers Theodorus Welzen and Adrianus de Vaan invented a video speed-drive scheme that solved the slow response time of STN-LCDs, enabling high-resolution, high-quality, and smooth-moving video images on STN-LCDs. In 1985, Philips inventors Theodorus Welzen and Adrianus de Vaan solved the problem of driving high-resolution STN-LCDs using low-voltage (CMOS-based) drive electronics, allowing the application of high-quality (high resolution and video speed) LCD panels in battery-operated portable products like notebook computers and mobile phones.[56] In 1985, Philips acquired 100% of the Videlec AG company based in Switzerland. Afterwards, Philips moved the Videlec production lines to the Netherlands. Years later, Philips successfully produced and marketed complete modules (consisting of the LCD screen, microphone, speakers etc.) in high-volume production for the booming mobile phone industry.

The first color LCD televisions were developed as handheld televisions in Japan. In 1980, Hattori Seiko's R&D group began development on color LCD pocket televisions.[57] In 1982, Seiko Epson released the first LCD television, the Epson TV Watch, a wristwatch equipped with a small active-matrix LCD television.[58][59] Sharp Corporation introduced dot matrix TN-LCD in 1983.[48] In 1984, Epson released the ET-10, the first full-color, pocket LCD television.[60] The same year, Citizen Watch,[61] introduced the Citizen Pocket TV,[57] a 2.7-inch color LCD TV,[61] with the first commercial TFT LCD.[57] In 1988, Sharp demonstrated a 14-inch, active-matrix, full-color, full-motion TFT-LCD. This led to Japan launching an LCD industry, which developed large-size LCDs, including TFT computer monitors and LCD televisions.[62] Epson developed the 3LCD projection technology in the 1980s, and licensed it for use in projectors in 1988.[63] Epson's VPJ-700, released in January 1989, was the world's first compact, full-color LCD projector.[59]

1990s

In 1990, under different titles, inventors conceived electro optical effects as alternatives to twisted nematic field effect LCDs (TN- and STN- LCDs). One approach was to use interdigital electrodes on one glass substrate only to produce an electric field essentially parallel to the glass substrates.[64][65] To take full advantage of the properties of this In Plane Switching (IPS) technology further work was needed. After thorough analysis, details of advantageous embodiments are filed in Germany by Guenter Baur et al. and patented in various countries.[66][67] The Fraunhofer Institute ISE in Freiburg, where the inventors worked, assigns these patents to Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, a supplier of LC substances. In 1992, shortly thereafter, engineers at Hitachi work out various practical details of the IPS technology to interconnect the thin-film transistor array as a matrix and to avoid undesirable stray fields in between pixels.[68][69] The first wall-mountable LCD TV was introduced by Sharp Corporation in 1992.[70]

Hitachi also improved the viewing angle dependence further by optimizing the shape of the electrodes (Super IPS). NEC and Hitachi become early manufacturers of active-matrix addressed LCDs based on the IPS technology. This is a milestone for implementing large-screen LCDs having acceptable visual performance for flat-panel computer monitors and television screens. In 1996, Samsung developed the optical patterning technique that enables multi-domain LCD. Multi-domain and In Plane Switching subsequently remain the dominant LCD designs through 2006.[71] In the late 1990s, the LCD industry began shifting away from Japan, towards South Korea and Taiwan,[62] and later on towards China.

2000s

In 2007 the image quality of LCD televisions surpassed the image quality of cathode-ray-tube-based (CRT) TVs.[72] In the fourth quarter of 2007, LCD televisions surpassed CRT TVs in worldwide sales for the first time.[73] LCD TVs were projected to account 50% of the 200 million TVs to be shipped globally in 2006, according to Displaybank.[74][75]

2010s

In October 2011, Toshiba announced 2560 × 1600 pixels on a 6.1-inch (155 mm) LCD panel, suitable for use in a tablet computer,[76] especially for Chinese character display. The 2010s also saw the wide adoption of TGP (Tracking Gate-line in Pixel), which moves the driving circuitry from the borders of the display to in between the pixels, allowing for narrow bezels.[77]

In 2016, Panasonic developed IPS LCDs with a contrast ratio of 1,000,000:1, rivaling OLEDs. This technology was later put into mass production as dual layer, dual panel or LMCL (Light Modulating Cell Layer) LCDs. The technology uses 2 liquid crystal layers instead of one, and may be used along with a mini-LED backlight and quantum dot sheets.[78][79]

Illumination

Since LCDs produce no light of their own, they require external light to produce a visible image.[80][81] In a transmissive type of LCD, the light source is provided at the back of the glass stack and is called a backlight. Active-matrix LCDs are almost always backlit.[82][83] Passive LCDs may be backlit but many use a reflector at the back of the glass stack to utilize ambient light. Transflective LCDs combine the features of a backlit transmissive display and a reflective display.

The common implementations of LCD backlight technology are:

- CCFL: The LCD panel is lit either by two cold cathode fluorescent lamps placed at opposite edges of the display or an array of parallel CCFLs behind larger displays. A diffuser (made of PMMA acrylic plastic, also known as a wave or light guide/guiding plate[84][85]) then spreads the light out evenly across the whole display. For many years, this technology had been used almost exclusively. Unlike white LEDs, most CCFLs have an even-white spectral output resulting in better color gamut for the display. However, CCFLs are less energy efficient than LEDs and require a somewhat costly inverter to convert whatever DC voltage the device uses (usually 5 or 12 V) to ≈1000 V needed to light a CCFL.[86] The thickness of the inverter transformers also limits how thin the display can be made.

- EL-WLED: The LCD panel is lit by a row of white LEDs placed at one or more edges of the screen. A light diffuser (light guide plate, LGP) is then used to spread the light evenly across the whole display, similarly to edge-lit CCFL LCD backlights. The diffuser is made out of either PMMA plastic or special glass, PMMA is used in most cases because it is rugged, while special glass is used when the thickness of the LCD is of primary concern, because it doesn't expand as much when heated or exposed to moisture, which allows LCDs to be just 5mm thick. Quantum dots may be placed on top of the diffuser as a quantum dot enhancement film (QDEF, in which case they need a layer to be protected from heat and humidity) or on the color filter of the LCD, replacing the resists that are normally used.[84] As of 2012, this design is the most popular one in desktop computer monitors. It allows for the thinnest displays. Some LCD monitors using this technology have a feature called dynamic contrast, invented by Philips researchers Douglas Stanton, Martinus Stroomer and Adrianus de Vaan[87] Using PWM (pulse-width modulation, a technology where the intensity of the LEDs are kept constant, but the brightness adjustment is achieved by varying a time interval of flashing these constant light intensity light sources[88]), the backlight is dimmed to the brightest color that appears on the screen while simultaneously boosting the LCD contrast to the maximum achievable levels, allowing the 1000:1 contrast ratio of the LCD panel to be scaled to different light intensities, resulting in the "30000:1" contrast ratios seen in the advertising on some of these monitors. Since computer screen images usually have full white somewhere in the image, the backlight will usually be at full intensity, making this "feature" mostly a marketing gimmick for computer monitors, however for TV screens it drastically increases the perceived contrast ratio and dynamic range, improves the viewing angle dependency and drastically reducing the power consumption of conventional LCD televisions.

- WLED array: The LCD panel is lit by a full array of white LEDs placed behind a diffuser behind the panel. LCDs that use this implementation will usually have the ability to dim or completely turn off the LEDs in the dark areas of the image being displayed, effectively increasing the contrast ratio of the display. The precision with which this can be done will depend on the number of dimming zones of the display. The more dimming zones, the more precise the dimming, with less obvious blooming artifacts which are visible as dark grey patches surrounded by the unlit areas of the LCD. As of 2012, this design gets most of its use from upscale, larger-screen LCD televisions.

- RGB-LED array: Similar to the WLED array, except the panel is lit by a full array of RGB LEDs. While displays lit with white LEDs usually have a poorer color gamut than CCFL lit displays, panels lit with RGB LEDs have very wide color gamuts. This implementation is most popular on professional graphics editing LCDs. As of 2012, LCDs in this category usually cost more than $1000. As of 2016 the cost of this category has drastically reduced and such LCD televisions obtained same price levels as the former 28" (71 cm) CRT based categories.

- Monochrome LEDs: such as red, green, yellow or blue LEDs are used in the small passive monochrome LCDs typically used in clocks, watches and small appliances.

- Mini-LED: Backlighting with Mini-LEDs can support over a thousand of Full-area Local Area Dimming (FLAD) zones. This allows deeper blacks and higher contrast ratio.[89]

Today, most LCD screens are being designed with an LED backlight instead of the traditional CCFL backlight, while that backlight is dynamically controlled with the video information (dynamic backlight control). The combination with the dynamic backlight control, invented by Philips researchers Douglas Stanton, Martinus Stroomer and Adrianus de Vaan, simultaneously increases the dynamic range of the display system (also marketed as HDR, high dynamic range television or FLAD, full-area local area dimming).[90][91][87]

The LCD backlight systems are made highly efficient by applying optical films such as prismatic structure (prism sheet) to gain the light into the desired viewer directions and reflective polarizing films that recycle the polarized light that was formerly absorbed by the first polarizer of the LCD (invented by Philips researchers Adrianus de Vaan and Paulus Schaareman),[92] generally achieved using so called DBEF films manufactured and supplied by 3M.[93] Improved versions of the prism sheet have a wavy rather than a prismatic structure, and introduce waves laterally into the structure of the sheet while also varying the height of the waves, directing even more light towards the screen and reducing aliasing or moiré between the structure of the prism sheet and the subpixels of the LCD. A wavy structure is easier to mass-produce than a prismatic one using conventional diamond machine tools, which are used to make the rollers used to imprint the wavy structure into plastic sheets, thus producing prism sheets.[94] A diffuser sheet is placed on both sides of the prism sheet to make the light of the backlight, uniform, while a mirror is placed behind the light guide plate to direct all light forwards. The prism sheet with its diffuser sheets are placed on top of the light guide plate.[95][84] The DBEF polarizers consist of a large stack of uniaxial oriented birefringent films that reflect the former absorbed polarization mode of the light.[96] Such reflective polarizers using uniaxial oriented polymerized liquid crystals (birefringent polymers or birefringent glue) are invented in 1989 by Philips researchers Dirk Broer, Adrianus de Vaan and Joerg Brambring.[97] The combination of such reflective polarizers, and LED dynamic backlight control[87] make today's LCD televisions far more efficient than the CRT-based sets, leading to a worldwide energy saving of 600 TWh (2017), equal to 10% of the electricity consumption of all households worldwide or equal to 2 times the energy production of all solar cells in the world.[98][99]

Connection to other circuits

A standard television receiver screen, a modern LCD panel, has over six million pixels, and they are all individually powered by a wire network embedded in the screen. The fine wires, or pathways, form a grid with vertical wires across the whole screen on one side of the screen and horizontal wires across the whole screen on the other side of the screen. To this grid each pixel has a positive connection on one side and a negative connection on the other side. So the total amount of wires needed for a 1080p display is 3 x 1920 going vertically and 1080 going horizontally for a total of 6840 wires horizontally and vertically. That's three for red, green and blue and 1920 columns of pixels for each color for a total of 5760 wires going vertically and 1080 rows of wires going horizontally. For a panel that is 28.8 inches (73 centimeters) wide, that means a wire density of 200 wires per inch along the horizontal edge.

The LCD panel is powered by LCD drivers that are carefully matched up with the edge of the LCD panel at the factory level. The drivers may be installed using several methods, the most common of which are COG (Chip-On-Glass) and TAB (Tape-automated bonding) These same principles apply also for smartphone screens that are much smaller than TV screens.[100][101][102] LCD panels typically use thinly-coated metallic conductive pathways on a glass substrate to form the cell circuitry to operate the panel. It is usually not possible to use soldering techniques to directly connect the panel to a separate copper-etched circuit board. Instead, interfacing is accomplished using anisotropic conductive film or, for lower densities, elastomeric connectors.

Passive-matrix

Monochrome and later color passive-matrix LCDs were standard in most early laptops (although a few used plasma displays[103][104]) and the original Nintendo Game Boy[105] until the mid-1990s, when color active-matrix became standard on all laptops. The commercially unsuccessful Macintosh Portable (released in 1989) was one of the first to use an active-matrix display (though still monochrome). Passive-matrix LCDs are still used in the 2010s for applications less demanding than laptop computers and TVs, such as inexpensive calculators. In particular, these are used on portable devices where less information content needs to be displayed, lowest power consumption (no backlight) and low cost are desired or readability in direct sunlight is needed.

Displays having a passive-matrix structure are employing super-twisted nematic STN (invented by Brown Boveri Research Center, Baden, Switzerland, in 1983; scientific details were published[106]) or double-layer STN (DSTN) technology (the latter of which addresses a color-shifting problem with the former), and color-STN (CSTN) in which color is added by using an internal filter. STN LCDs have been optimized for passive-matrix addressing. They exhibit a sharper threshold of the contrast-vs-voltage characteristic than the original TN LCDs. This is important, because pixels are subjected to partial voltages even while not selected. Crosstalk between activated and non-activated pixels has to be handled properly by keeping the RMS voltage of non-activated pixels below the threshold voltage as discovered by Peter J. Wild in 1972,[107] while activated pixels are subjected to voltages above threshold (the voltages according to the "Alt & Pleshko" drive scheme).[108] Driving such STN displays according to the Alt & Pleshko drive scheme require very high line addressing voltages. Welzen and de Vaan invented an alternative drive scheme (a non "Alt & Pleshko" drive scheme) requiring much lower voltages, such that the STN display could be driven using low voltage CMOS technologies.[56]

STN LCDs have to be continuously refreshed by alternating pulsed voltages of one polarity during one frame and pulses of opposite polarity during the next frame. Individual pixels are addressed by the corresponding row and column circuits. This type of display is called passive-matrix addressed, because the pixel must retain its state between refreshes without the benefit of a steady electrical charge. As the number of pixels (and, correspondingly, columns and rows) increases, this type of display becomes less feasible. Slow response times and poor contrast are typical of passive-matrix addressed LCDs with too many pixels and driven according to the "Alt & Pleshko" drive scheme. Welzen and de Vaan also invented a non RMS drive scheme enabling to drive STN displays with video rates and enabling to show smooth moving video images on an STN display. Citizen, among others, licensed these patents and successfully introduced several STN based LCD pocket televisions on the market.

Bistable LCDs do not require continuous refreshing. Rewriting is only required for picture information changes. In 1984 HA van Sprang and AJSM de Vaan invented an STN type display that could be operated in a bistable mode, enabling extremely high resolution images up to 4000 lines or more using only low voltages.[109] Since a pixel may be either in an on-state or in an off state at the moment new information needs to be written to that particular pixel, the addressing method of these bistable displays is rather complex, a reason why these displays did not made it to the market. That changed when in the 2010 "zero-power" (bistable) LCDs became available. Potentially, passive-matrix addressing can be used with devices if their write/erase characteristics are suitable, which was the case for ebooks which need to show still pictures only. After a page is written to the display, the display may be cut from the power while retaining readable images. This has the advantage that such ebooks may be operated for long periods of time powered by only a small battery.

High-resolution color displays, such as modern LCD computer monitors and televisions, use an active-matrix structure. A matrix of thin-film transistors (TFTs) is added to the electrodes in contact with the LC layer. Each pixel has its own dedicated transistor, allowing each column line to access one pixel. When a row line is selected, all of the column lines are connected to a row of pixels and voltages corresponding to the picture information are driven onto all of the column lines. The row line is then deactivated and the next row line is selected. All of the row lines are selected in sequence during a refresh operation. Active-matrix addressed displays look brighter and sharper than passive-matrix addressed displays of the same size, and generally have quicker response times, producing much better images. Sharp produces bistable reflective LCDs with a 1-bit SRAM cell per pixel that only requires small amounts of power to maintain an image.[110]

Segment LCDs can also have color by using Field Sequential Color (FSC LCD). This kind of displays have a high speed passive segment LCD panel with an RGB backlight. The backlight quickly changes color, making it appear white to the naked eye. The LCD panel is synchronized with the backlight. For example, to make a segment appear red, the segment is only turned ON when the backlight is red, and to make a segment appear magenta, the segment is turned ON when the backlight is blue, and it continues to be ON while the backlight becomes red, and it turns OFF when the backlight becomes green. To make a segment appear black, the segment is always turned ON. An FSC LCD divides a color image into 3 images (one Red, one Green and one Blue) and it displays them in order. Due to persistence of vision, the 3 monochromatic images appear as one color image. An FSC LCD needs an LCD panel with a refresh rate of 180 Hz, and the response time is reduced to just 5 milliseconds when compared with normal STN LCD panels which have a response time of 16 milliseconds.[111][112][113][114] FSC LCDs contain a Chip-On-Glass driver IC can also be used with a capacitive touchscreen.

Samsung introduced UFB (Ultra Fine & Bright) displays back in 2002, utilized the super-birefringent effect. It has the luminance, color gamut, and most of the contrast of a TFT-LCD, but only consumes as much power as an STN display, according to Samsung. It was being used in a variety of Samsung cellular-telephone models produced until late 2006, when Samsung stopped producing UFB displays. UFB displays were also used in certain models of LG mobile phones.

Active-matrix technologies

Twisted nematic (TN)

Twisted nematic displays contain liquid crystals that twist and untwist at varying degrees to allow light to pass through. When no voltage is applied to a TN liquid crystal cell, polarized light passes through the 90-degrees twisted LC layer. In proportion to the voltage applied, the liquid crystals untwist changing the polarization and blocking the light's path. By properly adjusting the level of the voltage almost any gray level or transmission can be achieved.

In-plane switching (IPS)

In-plane switching is an LCD technology that aligns the liquid crystals in a plane parallel to the glass substrates. In this method, the electrical field is applied through opposite electrodes on the same glass substrate, so that the liquid crystals can be reoriented (switched) essentially in the same plane, although fringe fields inhibit a homogeneous reorientation. This requires two transistors for each pixel instead of the single transistor needed for a standard thin-film transistor (TFT) display. The IPS technology is used in everything from televisions, computer monitors, and even wearable devices, especially almost all LCD smartphone panels are IPS/FFS mode. IPS displays belong to the LCD panel family screen types. The other two types are VA and TN. Before LG Enhanced IPS was introduced in 2001 by Hitachi as 17" monitor in Market, the additional transistors resulted in blocking more transmission area, thus requiring a brighter backlight and consuming more power, making this type of display less desirable for notebook computers. Panasonic Himeji G8.5 was using an enhanced version of IPS, also LGD in Korea, then currently the world biggest LCD panel manufacture BOE in China is also IPS/FFS mode TV panel.

Super In-plane switching (S-IPS)

Super-IPS was later introduced after in-plane switching with even better response times and color reproduction.[115]

M+ or RGBW controversy

In 2015 LG Display announced the implementation of a new technology called M+ which is the addition of white subpixel along with the regular RGB dots in their IPS panel technology.[116]

Most of the new M+ technology was employed on 4K TV sets which led to a controversy after tests showed that the addition of a white sub pixel replacing the traditional RGB structure would reduce the resolution by around 25%. This means that a 4K TV cannot display the full UHD TV standard. The media and internet users later called this "RGBW" TVs because of the white sub pixel. Although LG Display has developed this technology for use in notebook display, outdoor and smartphones, it became more popular in the TV market because the announced 4K UHD resolution but still being incapable of achieving true UHD resolution defined by the CTA as 3840x2160 active pixels with 8-bit color. This negatively impacts the rendering of text, making it a bit fuzzier, which is especially noticeable when a TV is used as a PC monitor.[117][118][119][120]

IPS in comparison to AMOLED

In 2011, LG claimed the smartphone LG Optimus Black (IPS LCD (LCD NOVA)) has the brightness up to 700 nits, while the competitor has only IPS LCD with 518 nits and double an active-matrix OLED (AMOLED) display with 305 nits. LG also claimed the NOVA display to be 50 percent more efficient than regular LCDs and to consume only 50 percent of the power of AMOLED displays when producing white on screen.[121] When it comes to contrast ratio, AMOLED display still performs best due to its underlying technology, where the black levels are displayed as pitch black and not as dark gray. On August 24, 2011, Nokia announced the Nokia 701 and also made the claim of the world's brightest display at 1000 nits. The screen also had Nokia's Clearblack layer, improving the contrast ratio and bringing it closer to that of the AMOLED screens.

Advanced fringe field switching (AFFS)

Known as fringe field switching (FFS) until 2003,[122] advanced fringe field switching is similar to IPS or S-IPS offering superior performance and color gamut with high luminosity. AFFS was developed by Hydis Technologies Co., Ltd, Korea (formally Hyundai Electronics, LCD Task Force).[123] AFFS-applied notebook applications minimize color distortion while maintaining a wider viewing angle for a professional display. Color shift and deviation caused by light leakage is corrected by optimizing the white gamut which also enhances white/gray reproduction. In 2004, Hydis Technologies Co., Ltd licensed AFFS to Japan's Hitachi Displays. Hitachi is using AFFS to manufacture high-end panels. In 2006, HYDIS licensed AFFS to Sanyo Epson Imaging Devices Corporation. Shortly thereafter, Hydis introduced a high-transmittance evolution of the AFFS display, called HFFS (FFS+). Hydis introduced AFFS+ with improved outdoor readability in 2007. AFFS panels are mostly utilized in the cockpits of latest commercial aircraft displays. However, it is no longer produced as of February 2015.[124][125][126]

Vertical alignment (VA)

Vertical-alignment displays are a form of LCDs in which the liquid crystals naturally align vertically to the glass substrates. When no voltage is applied, the liquid crystals remain perpendicular to the substrate, creating a black display between crossed polarizers. When voltage is applied, the liquid crystals shift to a tilted position, allowing light to pass through and create a gray-scale display depending on the amount of tilt generated by the electric field. It has a deeper-black background, a higher contrast ratio, a wider viewing angle, and better image quality at extreme temperatures than traditional twisted-nematic displays.[127] Compared to IPS, the black levels are still deeper, allowing for a higher contrast ratio, but the viewing angle is narrower, with color and especially contrast shift being more apparent.[128]

Blue phase mode

Blue phase mode LCDs have been shown as engineering samples early in 2008, but they are not in mass-production. The physics of blue phase mode LCDs suggest that very short switching times (≈1 ms) can be achieved, so time sequential color control can possibly be realized and expensive color filters would be obsolete.

Quality control

Some LCD panels have defective transistors, causing permanently lit or unlit pixels which are commonly referred to as stuck pixels or dead pixels respectively. Unlike integrated circuits (ICs), LCD panels with a few defective transistors are usually still usable. Manufacturers' policies for the acceptable number of defective pixels vary greatly. At one point, Samsung held a zero-tolerance policy for LCD monitors sold in Korea.[129] As of 2005, Samsung adheres to the less restrictive ISO 13406-2 standard.[130] Other companies have been known to tolerate as many as 11 dead pixels in their policies.[131]

Dead pixel policies are often hotly debated between manufacturers and customers. To regulate the acceptability of defects and to protect the end user, ISO released the ISO 13406-2 standard, which was made obsolete in 2008 with the release of ISO 9241, specifically ISO-9241-302, 303, 305, 307:2008 pixel defects. However, not every LCD manufacturer conforms to the ISO standard and the ISO standard is quite often interpreted in different ways. LCD panels are more likely to have defects than most ICs due to their larger size.

Some manufacturers, notably in South Korea where some of the largest LCD panel manufacturers, such as LG, are located, now have a zero-defective-pixel guarantee, which is an extra screening process which can then determine "A"- and "B"-grade panels. Many manufacturers would replace a product even with one defective pixel. Even where such guarantees do not exist, the location of defective pixels is important. A display with only a few defective pixels may be unacceptable if the defective pixels are near each other. LCD panels also have defects known as clouding (or less commonly mura), which describes the uneven patches of changes in luminance. It is most visible in dark or black areas of displayed scenes.[132] As of 2010, most premium branded computer LCD panel manufacturers specify their products as having zero defects.

"Zero-power" (bistable) displays

The zenithal bistable device (ZBD), developed by Qinetiq (formerly DERA), can retain an image without power. The crystals may exist in one of two stable orientations ("black" and "white") and power is only required to change the image. ZBD Displays is a spin-off company from QinetiQ who manufactured both grayscale and color ZBD devices. Kent Displays has also developed a "no-power" display that uses polymer stabilized cholesteric liquid crystal (ChLCD). In 2009 Kent demonstrated the use of a ChLCD to cover the entire surface of a mobile phone, allowing it to change colors, and keep that color even when power is removed.[133]

In 2004, researchers at the University of Oxford demonstrated two new types of zero-power bistable LCDs based on Zenithal bistable techniques.[134] Several bistable technologies, like the 360° BTN and the bistable cholesteric, depend mainly on the bulk properties of the liquid crystal (LC) and use standard strong anchoring, with alignment films and LC mixtures similar to the traditional monostable materials. Other bistable technologies, e.g., BiNem technology, are based mainly on the surface properties and need specific weak anchoring materials.

Specifications

- Resolution The resolution of an LCD is expressed by the number of columns and rows of pixels (e.g., 1024×768). Each pixel is usually composed 3 sub-pixels, a red, a green, and a blue one. This had been one of the few features of LCD performance that remained uniform among different designs. However, there are newer designs that share sub-pixels among pixels and add Quattron which attempt to efficiently increase the perceived resolution of a display without increasing the actual resolution, to mixed results.

- Spatial performance: For a computer monitor or some other display that is being viewed from a very close distance, resolution is often expressed in terms of dot pitch or pixels per inch, which is consistent with the printing industry. Display density varies per application, with televisions generally having a low density for long-distance viewing and portable devices having a high density for close-range detail. The Viewing Angle of an LCD may be important depending on the display and its usage, the limitations of certain display technologies mean the display only displays accurately at certain angles.

- Temporal performance: the temporal resolution of an LCD is how well it can display changing images, or the accuracy and the number of times per second the display draws the data it is being given. LCD pixels do not flash on/off between frames, so LCD monitors exhibit no refresh-induced flicker no matter how low the refresh rate.[135] But a lower refresh rate can mean visual artefacts like ghosting or smearing, especially with fast moving images. Individual pixel response time is also important, as all displays have some inherent latency in displaying an image which can be large enough to create visual artifacts if the displayed image changes rapidly.

- Color performance: There are multiple terms to describe different aspects of color performance of a display. Color gamut is the range of colors that can be displayed, and color depth, which is the fineness with which the color range is divided. Color gamut is a relatively straight forward feature, but it is rarely discussed in marketing materials except at the professional level. Having a color range that exceeds the content being shown on the screen has no benefits, so displays are only made to perform within or below the range of a certain specification.[136] There are additional aspects to LCD color and color management, such as white point and gamma correction, which describe what color white is and how the other colors are displayed relative to white.

- Brightness and contrast ratio: Contrast ratio is the ratio of the brightness of a full-on pixel to a full-off pixel. The LCD itself is only a light valve and does not generate light; the light comes from a backlight that is either fluorescent or a set of LEDs. Brightness is usually stated as the maximum light output of the LCD, which can vary greatly based on the transparency of the LCD and the brightness of the backlight. Brighter backlight allows stronger contrast and higher dynamic range (HDR displays are graded in peak luminance), but there is always a trade-off between brightness and power consumption.

Advantages and disadvantages

Some of these issues relate to full-screen displays, others to small displays as on watches, etc. Many of the comparisons are with CRT displays.

Advantages

- Very compact, thin and light, especially in comparison with bulky, heavy CRT displays.

- Low power consumption. Depending on the set display brightness and content being displayed, the older CCFT backlit models typically use less than half of the power a CRT monitor of the same size viewing area would use, and the modern LED backlit models typically use 10–25% of the power a CRT monitor would use.[137]

- Little heat emitted during operation, due to low power consumption.

- No geometric distortion.

- The possible ability to have little or no flicker depending on backlight technology.

- Usually no refresh-rate flicker, because the LCD pixels hold their state between refreshes (which are usually done at 200 Hz or faster, regardless of the input refresh rate).

- Sharp image with no bleeding or smearing when operated at native resolution.

- Emits almost no undesirable electromagnetic radiation (in the extremely low frequency range), unlike a CRT monitor.

- Can be made in almost any size or shape.

- No theoretical resolution limit. When multiple LCD panels are used together to create a single canvas, each additional panel increases the total resolution of the display, which is commonly called stacked resolution.[138]

- Can be made in large sizes of over 80-inch (2 m) diagonal.

- LCDs can be made transparent and flexible, but they cannot emit light without a backlight like OLED and microLED, which are other technologies that can also be made flexible and transparent.[139][140][141][142]

- Masking effect: the LCD grid can mask the effects of spatial and grayscale quantization, creating the illusion of higher image quality.[143]

- Unaffected by magnetic fields, including the Earth's, unlike most color CRTs.

- As an inherently digital device, the LCD can natively display digital data from a DVI or HDMI connection without requiring conversion to analog. Some LCD panels have native fiber-optic inputs in addition to DVI and HDMI.[144]

- Many LCD monitors are powered by a 12 V power supply, and if built into a computer can be powered by its 12 V power supply.

- Can be made with very narrow frame borders, allowing multiple LCD screens to be arrayed side by side to make up what looks like one big screen.

Disadvantages

- Limited viewing angle in some older or cheaper monitors, causing color, saturation, contrast and brightness to vary with user position, even within the intended viewing angle. Special films can be used to increase the viewing angles of LCDs.[145][146]

- Uneven backlighting in some monitors (more common in IPS-types and older TNs), causing brightness distortion, especially toward the edges ("backlight bleed").

- Black levels may not be as dark as required because individual liquid crystals cannot completely block all of the backlight from passing through.

- Display motion blur on moving objects caused by slow response times (>8 ms) and eye-tracking on a sample-and-hold display, unless a strobing backlight is used. However, this strobing can cause eye strain, as is noted next:

- As of 2012, most implementations of LCD backlighting use pulse-width modulation (PWM) to dim the display,[147] which makes the screen flicker more acutely (this does not mean visibly) than a CRT monitor at 85 Hz refresh rate would (this is because the entire screen is strobing on and off rather than a CRT's phosphor sustained dot which continually scans across the display, leaving some part of the display always lit), causing severe eye-strain for some people.[148][149] Unfortunately, many of these people don't know that their eye-strain is being caused by the invisible strobe effect of PWM.[150] This problem is worse on many LED-backlit monitors, because the LEDs switch on and off faster than a CCFL lamp.

- Only one native resolution. Displaying any other resolution either requires a video scaler, causing blurriness and jagged edges, or running the display at native resolution using 1:1 pixel mapping, causing the image either not to fill the screen (letterboxed display), or to run off the lower or right edges of the screen.

- Fixed bit depth (also called color depth). Many cheaper LCDs are only able to display 262144 (218) colors. 8-bit S-IPS panels can display 16 million (224) colors and have significantly better black level, but are expensive and have slower response time.

- Input lag, because the LCD's A/D converter waits for each frame to be completely been output before drawing it to the LCD panel. Many LCD monitors do post-processing before displaying the image in an attempt to compensate for poor color fidelity, which adds an additional lag. Further, a video scaler must be used when displaying non-native resolutions, which adds yet more time lag. Scaling and post processing are usually done in a single chip on modern monitors, but each function that chip performs adds some delay. Some displays have a video gaming mode which disables all or most processing to reduce perceivable input lag.

- Dead or stuck pixels may occur during manufacturing or after a period of use. A stuck pixel will glow with color even on an all-black screen, while a dead one will always remain black.

- Subject to burn-in effect, although the cause differs from CRT and the effect may not be permanent, a static image can cause burn-in in a matter of hours in badly designed displays.

- In a constant-on situation, thermalization may occur in case of bad thermal management, in which part of the screen has overheated and looks discolored compared to the rest of the screen.

- Loss of brightness and much slower response times in low temperature environments. In sub-zero environments, LCD screens may cease to function without the use of supplemental heating.

- Loss of contrast in high temperature environments.

Chemicals used

Several different families of liquid crystals are used in liquid crystal displays. The molecules used have to be anisotropic, and to exhibit mutual attraction. Polarizable rod-shaped molecules (biphenyls, terphenyls, etc.) are common. A common form is a pair of aromatic benzene rings, with a nonpolar moiety (pentyl, heptyl, octyl, or alkyl oxy group) on one end and polar (nitrile, halogen) on the other. Sometimes the benzene rings are separated with an acetylene group, ethylene, CH=N, CH=NO, N=N, N=NO, or ester group. In practice, eutectic mixtures of several chemicals are used, to achieve wider temperature operating range (−10..+60 °C for low-end and −20..+100 °C for high-performance displays). For example, the E7 mixture is composed of three biphenyls and one terphenyl: 39 wt.% of 4'-pentyl[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (nematic range 24..35 °C), 36 wt.% of 4'-heptyl[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (nematic range 30..43 °C), 16 wt.% of 4'-octoxy[1,1'-biphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (nematic range 54..80 °C), and 9 wt.% of 4-pentyl[1,1':4',1-terphenyl]-4-carbonitrile (nematic range 131..240 °C).[151]

Environmental impact

The production of LCD screens uses nitrogen trifluoride (NF3) as an etching fluid during the production of the thin-film components. NF3 is a potent greenhouse gas, and its relatively long half-life may make it a potentially harmful contributor to global warming. A report in Geophysical Research Letters suggested that its effects were theoretically much greater than better-known sources of greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide. As NF3 was not in widespread use at the time, it was not made part of the Kyoto Protocols and has been deemed "the missing greenhouse gas".[152]

Critics of the report point out that it assumes that all of the NF3 produced would be released to the atmosphere. In reality, the vast majority of NF3 is broken down during the cleaning processes; two earlier studies found that only 2 to 3% of the gas escapes destruction after its use.[153] Furthermore, the report failed to compare NF3's effects with what it replaced, perfluorocarbon, another powerful greenhouse gas, of which anywhere from 30 to 70% escapes to the atmosphere in typical use.[153]

See also

References

- ↑ Ulrich, Lawrence (2020). "Bosch's smart visual visor tracks sun". Archived March 1, 2021, at the Wayback Machine IEEE Spectrum, January 29, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Definition of LCD". Merriam-Webster.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ↑ "LCD Image Persistence". Fujitsu technical support. Fujitsu. Archived from the original on April 23, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Liquid crystal composition and liquid crystal display device". Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ↑ "Liquid crystal composition". Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ↑ Tien, Chuen-Lin; Lin, Rong-Ji; Yeh, Shang-Min (June 3, 2018). "Light Leakage of Multidomain Vertical Alignment LCDs Using a Colorimetric Model in the Dark State". Advances in Condensed Matter Physics. 2018: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2018/6386428.

- ↑ Castellano, Joseph A. (2005). Liquid Gold: The Story of Liquid Crystal Displays and the Creation of an Industry. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN 978-981-238-956-5.

- ↑ Koo, Horng-Show; Chen, Mi; Pan, Po-Chuan (November 1, 2006). "LCD-based color filter films fabricated by a pigment-based colorant photo resist inks and printing technology". Thin Solid Films. 515 (3): 896–901. Bibcode:2006TSF...515..896K. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2006.07.159 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ Rong-Jer Lee; Jr-Cheng Fan; Tzong-Shing Cheng; Jung-Lung Wu (March 10, 1999). "Pigment-dispersed color resist with high resolution for advanced color filter application". Proceedings of 5th Asian Symposium on Information Display. ASID '99 (IEEE Cat. No.99EX291). pp. 359–363. doi:10.1109/ASID.1999.762781. ISBN 957-97347-9-8. S2CID 137460486 – via IEEE Xplore.

- ↑ "Multi-colored liquid crystal display device". Archived from the original on May 22, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ↑ fx9750G PLUS, CFX-9850G PLUS, CFX-9850GB PLUS, CFX-9850GC PLUS, CFX-9950GC PLUS User's Guide (PDF). London, UK: Casio. pp. Page 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ↑ Datta, Asit Kumar; Munshi, Soumika (November 25, 2016). Information Photonics: Fundamentals, Technologies, and Applications. CRC Press. ISBN 9781482236422.

- ↑ "Sunic system". sunic.co.kr. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 AU Optronics Corp. (AUO): "Size Matters" Archived August 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine January 19, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Gan, Fuxi: From Optical Glass to Photonic Glass, Photonic Glasses, Pages 1–38.

- ↑ Armorex Taiwan Central Glass Company Archived February 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ↑ Samsung: SAMSUNG Electronics Announces 7th-Generation TFT LCD Glass Substrate Archived April 4, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Press release March 27, 2003, Visited August 2, 2010.

- 1 2 "Large Generation Glass". Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- 1 2 3 "8.6G Fabs, Do We Really Need Them? - Display Supply Chain Consultants". March 7, 2017. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ↑ "Company History - Sakai Display Products Corporation". SDP.co.jp. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ↑ Shih, Willy. "How Did They Make My Big-Screen TV? A Peek Inside China's Massive BOE Gen 10.5 Factory". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ↑ "BOE's Gen 10.5 Display Equipment Is a Pie in the Sky for Korean Equipment Companies". ETNews. July 10, 2015. Archived from the original on March 25, 2021.

- ↑ Castellano, Joseph A. (2005). Liquid Gold: The Story of Liquid Crystal Displays and the Creation of an Industry. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. ISBN 981-238-956-3.

- ↑ Kawamoto, Hiroshi (2002). "The History of Liquid-Crystal Displays" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 90 (4): 460–500. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2002.1002521. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2009.

- ↑ "First-Hand Histories: Liquid Crystal Display Evolution — Swiss Contributions". Engineering and Technology History Wiki. ETHW. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ↑ Jonathan W. Steed & Jerry L. Atwood (2009). Supramolecular Chemistry (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 844. ISBN 978-0-470-51234-0.

- ↑ Reinitzer, Friedrich (1888). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss des Cholesterins". Monatshefte für Chemie und verwandte Teile anderer Wissenschaften (in German). 9 (1): 421–441. doi:10.1007/BF01516710. ISSN 0026-9247. S2CID 97166902.

- ↑ Gray, George W.; Kelly, Stephen M. (1999). "Liquid crystals for twisted nematic display devices". Journal of Materials Chemistry. 9 (9): 2037–2050. doi:10.1039/a902682g.

- ↑ Williams, R. (1963). "Domains in liquid crystals". J. Phys. Chem. 39 (2): 382–388. Bibcode:1963JChPh..39..384W. doi:10.1063/1.1734257.

- ↑ Weimer, Paul K. (1962). "The TFT A New Thin-Film Transistor". Proceedings of the IRE. 50 (6): 1462–1469. doi:10.1109/JRPROC.1962.288190. ISSN 0096-8390. S2CID 51650159.

- ↑ Kimizuka, Noboru; Yamazaki, Shunpei (2016). Physics and Technology of Crystalline Oxide Semiconductor CAAC-IGZO: Fundamentals. John Wiley & Sons. p. 217. ISBN 9781119247401.

- 1 2 Castellano, Joseph A. (2006). "Modifying Light". American Scientist. 94 (5): 438–445. doi:10.1511/2006.61.438.

- ↑ Heilmeier, George; Castellano, Joseph; Zanoni, Louis (1969). "Guest-Host Interactions in Nematic Liquid Crystals". Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals. 8: 293–304. doi:10.1080/15421406908084910.

- ↑ Heilmeier, G. H.; Zanoni, L. A.; Barton, L. A. (1968). "Dynamic Scattering: A New Electrooptic Effect in Certain Classes of Nematic Liquid Crystals". Proc. IEEE. 56 (7): 1162–1171. doi:10.1109/proc.1968.6513.

- ↑ Gross, Benjamin (November 2012). "How RCA lost the LCD". IEEE Spectrum. 49 (11): 38–44. doi:10.1109/mspec.2012.6341205. S2CID 7947164.

- ↑ National Inventors Hall of Fame Archived April 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (Retrieved April 25, 2014)

- ↑ "Milestones: Liquid Crystal Display, 1968". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Archived from the original on November 18, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- 1 2 Kawamoto, H. (2012). "The Inventors of TFT Active-Matrix LCD Receive the 2011 IEEE Nishizawa Medal". Journal of Display Technology. 8 (1): 3–4. Bibcode:2012JDisT...8....3K. doi:10.1109/JDT.2011.2177740. ISSN 1551-319X.

- ↑ Castellano, Joseph A. (2005). Liquid Gold: The Story of Liquid Crystal Displays and the Creation of an Industry. World Scientific. pp. 41–2. ISBN 9789812389565.

- ↑ "Modifying Light". American Scientist Online. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- ↑ "Driving arrangement for passive time indicating devices". Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ↑ Brody, T. P., "Birth of the Active Matrix", Information Display, Vol. 13, No. 10, 1997, pp. 28–32.

- ↑ Kuo, Yue (January 1, 2013). "Thin Film Transistor Technology—Past, Present, and Future" (PDF). The Electrochemical Society Interface. 22 (1): 55–61. Bibcode:2013ECSIn..22a..55K. doi:10.1149/2.F06131if. ISSN 1064-8208. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2019.

- ↑ Brody, T. Peter; Asars, J. A.; Dixon, G. D. (November 1973). "A 6 × 6 inch 20 lines-per-inch liquid-crystal display panel". IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices. 20 (11): 995–1001. Bibcode:1973ITED...20..995B. doi:10.1109/T-ED.1973.17780. ISSN 0018-9383.

- ↑ Brotherton, S. D. (2013). Introduction to Thin Film Transistors: Physics and Technology of TFTs. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 74. ISBN 9783319000022.

- ↑ Dale, Rodney; Millichamp, David (September 28, 1972). "Liquid Crystals Get Their Sparkle From Mass Market". The Engineer: 34–36.

- ↑ "What's New In Electronics: 100-hour calculator". Popular Science: 87. December 1973.

- 1 2 Note on the Liquid Crystal Display Industry, Auburn University, 1995.

- ↑ Heilmeier, G. H., Castellano, J. A. and Zanoni, L. A.: Guest-host interaction in nematic liquid crystals. Mol. Cryst. Liquid Cryst. vol. 8, p. 295, 1969.

- ↑ "Liquid crystal display units". Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ↑ "Liquid crystal color display device". Archived from the original on March 26, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ↑ "Liquid crystal display device". Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ↑ "Liquid crystal display unit of matrix type". Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ↑ European Patent No. EP 0131216: Amstutz H., Heimgartner D., Kaufmann M., Scheffer T.J., "Flüssigkristallanzeige," October 28, 1987.

- ↑ Gessinger, Gernot H. (2009). Materials and Innovative Product development. Elsevier. p. 204. ISBN 9780080878201.

- 1 2 Low Drive Voltage Display Device; T.L. Welzen; A.J.S.M. de Vaan; European patent EP0221613B1; July 10, 1991, filed November 4, 1985; https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?CC=EP&NR=0221613B1&KC=B1&FT=D&ND=4&date=19910710&DB=EPODOC&locale=en_EP# Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine; US patent US4783653A; https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/originalDocument?CC=US&NR=4783653A&KC=A&FT=D&ND=5&date=19881108&DB=EPODOC&locale=en_EP# Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 Spin, Jul 1985, page 55

- ↑ "TV Watch - Epson". global.epson.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- 1 2 Michael R. Peres, The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography, page 306, Taylor & Francis

- ↑ A HISTORY OF CREATING INSPIRATIONAL TECHNOLOGY, Epson

- 1 2 Popular Science, May 1984, page 150

- 1 2 Hirohisa Kawamoto (2013), The history of liquid-crystal display and its industry Archived June 15, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, HISTory of ELectro-technology CONference (HISTELCON), 2012 Third IEEE, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, doi:10.1109/HISTELCON.2012.6487587

- ↑ Find out what is an LCD Projector, how does it benefit you, and the difference between LCD and 3LCD here Archived August 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Epson

- ↑ "Espacenet — Bibliographic data". Worldwide.espacenet.com. September 10, 1974. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 3,834,794: R. Soref, Liquid crystal electric field sensing measurement and display device, filed June 28, 1973.

- ↑ "Espacenet — Bibliographic data". Worldwide.espacenet.com. November 19, 1996. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 5,576,867: G. Baur, W. Fehrenbach, B. Staudacher, F. Windscheid, R. Kiefer, Liquid crystal switching elements having a parallel electric field and betao which is not 0 or 90 degrees, filed January 9, 1990.

- ↑ "Espacenet — Bibliographic data". Worldwide.espacenet.com. January 28, 1997. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ↑ U.S. Patent 5,598,285: K. Kondo, H. Terao, H. Abe, M. Ohta, K. Suzuki, T. Sasaki, G. Kawachi, J. Ohwada, Liquid crystal display device, filed September 18, 1992, and January 20, 1993.

- ↑ Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. January 1992. p. 87. ISSN 0161-7370. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ↑ "Optical Patterning" (PDF). Nature. August 22, 1996. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ↑ Competing display technologies for the best image performance; A.J.S.M. de Vaan; Journal of the society of information displays, Volume 15, Issue September 9, 2007, Pages 657–666; http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1889/1.2785199/abstract?

- ↑ "Worldwide LCD TV shipments surpass CRTs for first time ever". engadgetHD. February 19, 2008. Archived from the original on March 8, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Displaybank's Global TV Market Forecasts for 2008 – Global TV market to surpass 200 million units". Displaybank. December 5, 2007. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ↑ "IHS Acquires Displaybank, a Global Leader in Research and Consulting in the Flat-Panel Display Industry — IHS Technology". technology.ihs.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2020. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Toshiba announces 6.1 inch LCD panel with an insane resolution of 2560 x 1600 pixels". October 24, 2011. Archived from the original on October 26, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ↑ "Chunghwa Picture Tubes, LTD. - intro_Tech". archive.ph. December 23, 2019. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019.

- ↑ Morrison, Geoffrey. "Are dual-LCDs double the fun? New TV tech aims to find out". CNET. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Panasonic's OLED-fighting LCD is meant for professionals". Engadget. December 4, 2016. Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ↑ OECD (March 7, 2000). Information Technology Outlook 2000 ICTs, E-commerce and the Information Economy: ICTs, E-commerce and the Information Economy. OECD Publishing. ISBN 978-92-64-18103-8.

- ↑ Ibrahim, Dogan (August 22, 2012). Using LEDs, LCDs and GLCDs in Microcontroller Projects. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-36103-0.

- ↑ Explanation of different LCD monitor technologies, "Monitor buying guide — CNET Reviews" Archived March 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Eric Franklin, Retrieved September 2012.

- ↑ Explanation of different LCD monitor backlight technologies, "Monitor LED Backlighting" Archived May 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, TFT Central. Retrieved September 2012.

- 1 2 3 "LCD TVs Change Light Guide Plate Material to Enable Thinner TV". OLED Association. November 13, 2017. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ↑ "LCD optical waveguide device". Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ↑ Explanation of CCFL backlighting details, "Design News — Features — How to Backlight an LCD" Archived January 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Randy Frank, Retrieved January 2013.

- 1 2 3 Method of and device for generating an image having a desired brightness; D.A. Stanton; M.V.C. Stroomer; A.J.S.M. de Vaan; US patent USRE42428E; June 7, 2011; https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?CC=US&NR=RE42428E Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Moronski, J. (January 3, 2004). "Dimming options for LCD brightness". Electronicproducts.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017.

- ↑ Shafer, Rob (June 5, 2019). "Mini-LED vs MicroLED - What Is The Difference? [Simple Explanation]". DisplayNinja. Archived from the original on April 5, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ↑ Morrison, G. (March 26, 2016). "LED local dimming explained". CNET.com/news. Archived from the original on November 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Pixel-by-pixel local dimming for high dynamic range liquid crystal displays"; H. Chen; R. Zhu; M.C. Li; S.L. Lee and S.T. Wu; Vol. 25, No. 3; February 6, 2017; Optics Express 1973

- ↑ Illumination system and display device including such a system; A.J.S.M. de Vaan; P.B. Schaareman; European patent EP0606939B1; https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?CC=EP&NR=0606939B1&KC=B1&FT=D&ND=5&date=19980506&DB=EPODOC&locale=en_EP# Archived July 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Brochure 3M Display Materials & Systems Division Solutions for Large Displays: The right look matters; http://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/977332O/display-materials-systems-strategies-for-large-displays.pdf Archived August 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Prism sheet having prisms with wave pattern, black light unit including the prism sheet, and liquid crystal display device including the black light unit". Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ↑ "StackPath". LaserFocusWorld.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ↑ Broadband reflective polarizers based on form birefringence for ultra-thin liquid crystal displays; S.U. Pan; L. Tan and H.S. Kwok; Vol. 25, No. 15; July 24, 2017; Optics Express 17499; https://www.osapublishing.org/oe/viewmedia.cfm?uri=oe-25-15-17499&seq=0

- ↑ Polarisation-sensitive beam splitter; D.J. Broer; A.J.S.M. de Vaan; J. Brambring; European patent EP0428213B1; July 27, 1994; https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?CC=EP&NR=0428213B1&KC=B1&FT=D# Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Energy Efficiency Success Story: TV Energy Consumption Shrinks as Screen Size and Performance Grow, Finds New CTA Study; Consumer Technology Association; press release July 12, 2017; https://cta.tech/News/Press-Releases/2017/July/Energy-Efficiency-Success-Story-TV-Energy-Consump.aspx Archived November 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ LCD Television Power Draw Trends from 2003 to 2015; B. Urban and K. Roth; Fraunhofer USA Center for Sustainable Energy Systems; Final Report to the Consumer Technology Association; May 2017; http://www.cta.tech/cta/media/policyImages/policyPDFs/Fraunhofer-LCD-TV-Power-Draw-Trends-FINAL.pdf Archived August 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ LG Training Center. 2012 Understanding LCD T-CON Training Presentation, p. 7.

- ↑ "LCD (Liquid Crystal Display) Color Monitor Introduction, p. 14" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ↑ Future Electronics. Parts list, LCD Display Drivers.

- ↑ "Compaq Portable III". Archived from the original on January 2, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ Eric Wasatonicundefined (Director). IBM PS/2 P70 Portable Computer — Vintage PLASMA Display.

- ↑ "Game Boy: User Manual, page 12". February 12, 2011. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- ↑ T.J. Scheffer and J. Nehring,"A new highly multiplexable LCD," Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 48, no. 10, pp. 1021–1023, Nov. 1984.

- ↑ P. J. Wild, Matrix-addressed liquid crystal projection display, Digest of Technical Papers, International Symposium, Society for Information Display, June 1972, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ P. M. Alt, P. Pleshko Scanning limitations of liquid-crystal displays, IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, vol. ED-21, pp. 146–155, February 1974.

- ↑ Liquid Crystal Display Device with a hysteresis Archived March 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, HA van Sprang and AJSM de Vaan; European patent: EP0155033B1; January 31, 1990; filed February 24, 1984; https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/biblio?CC=EP&NR=0155033B1&KC=B1&FT=D&ND=4&date=19900131&DB=EPODOC&locale=en_EP# Archived March 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine; US patent US4664483A

- ↑ "Products - Sharp". www.sharpsma.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

- ↑ Product presentation Archived February 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine