| LCP array | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Array | |||||||||

| Invented by | Manber & Myers (1993) | |||||||||

| Time complexity and space complexity in big O notation | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

In computer science, the longest common prefix array (LCP array) is an auxiliary data structure to the suffix array. It stores the lengths of the longest common prefixes (LCPs) between all pairs of consecutive suffixes in a sorted suffix array.

For example, if A := [aab, ab, abaab, b, baab] is a suffix array, the longest common prefix between A[1] = aab and A[2] = ab is a which has length 1, so H[2] = 1 in the LCP array H. Likewise, the LCP of A[2] = ab and A[3] = abaab is ab, so H[3] = 2.

Augmenting the suffix array with the LCP array allows one to efficiently simulate top-down and bottom-up traversals of the suffix tree,[1][2] speeds up pattern matching on the suffix array[3] and is a prerequisite for compressed suffix trees.[4]

History

The LCP array was introduced in 1993, by Udi Manber and Gene Myers alongside the suffix array in order to improve the running time of their string search algorithm.[3]

Definition

Let be the suffix array of the string of length , where is a sentinel letter that is unique and lexicographically smaller than any other character. Let denote the substring of ranging from to . Thus, is the th smallest suffix of .

Let denote the length of the longest common prefix between two strings and . Then the LCP array is an integer array of size such that is undefined and for every . Thus stores the length of longest common prefix of the lexicographically th smallest suffix and its predecessor in the suffix array.

Difference between LCP array and suffix array:

- Suffix array: Represents the lexicographic rank of each suffix of an array.

- LCP array: Contains the maximum length prefix match between two consecutive suffixes, after they are sorted lexicographically.

Example

Consider the string :

| i | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S[i] | b | a | n | a | n | a | $ |

and its corresponding sorted suffix array :

| i | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A[i] | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

Suffix array with suffixes written out underneath vertically:

| i | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A[i] | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| S[A[i], n][1] | $ | a | a | a | b | n | n |

| S[A[i], n][2] | $ | n | n | a | a | a | |

| S[A[i], n][3] | a | a | n | $ | n | ||

| S[A[i], n][4] | $ | n | a | a | |||

| S[A[i], n][5] | a | n | $ | ||||

| S[A[i], n][6] | $ | a | |||||

| S[A[i], n][7] | $ |

Then the LCP array is constructed by comparing lexicographically consecutive suffixes to determine their longest common prefix:

| i | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H[i] | undefined | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

So, for example, is the length of the longest common prefix shared by the suffixes and . Note that is undefined, since there is no lexicographically smaller suffix.

Efficient construction algorithms

LCP array construction algorithms can be divided into two different categories: algorithms that compute the LCP array as a byproduct to the suffix array and algorithms that use an already constructed suffix array in order to compute the LCP values.

Manber & Myers (1993) provide an algorithm to compute the LCP array alongside the suffix array in time. Kärkkäinen & Sanders (2003) show that it is also possible to modify their time algorithm such that it computes the LCP array as well. Kasai et al. (2001) present the first time algorithm (FLAAP) that computes the LCP array given the text and the suffix array.

Assuming that each text symbol takes one byte and each entry of the suffix or LCP array takes 4 bytes, the major drawback of their algorithm is a large space occupancy of bytes, while the original output (text, suffix array, LCP array) only occupies bytes. Therefore, Manzini (2004) created a refined version of the algorithm of Kasai et al. (2001) (lcp9) and reduced the space occupancy to bytes. Kärkkäinen, Manzini & Puglisi (2009) provide another refinement of Kasai's algorithm (-algorithm) that improves the running time. Rather than the actual LCP array, this algorithm builds the permuted LCP (PLCP) array, in which the values appear in text order rather than lexicographical order.

Gog & Ohlebusch (2011) provide two algorithms that although being theoretically slow () were faster than the above-mentioned algorithms in practice.

As of 2012, the currently fastest linear-time LCP array construction algorithm is due to Fischer (2011), which in turn is based on one of the fastest suffix array construction algorithms (SA-IS) by Nong, Zhang & Chan (2009). Fischer & Kurpicz (2017) based on Yuta Mori's DivSufSort is even faster.

Applications

As noted by Abouelhoda, Kurtz & Ohlebusch (2004) several string processing problems can be solved by the following kinds of tree traversals:

- bottom-up traversal of the complete suffix tree

- top-down traversal of a subtree of the suffix tree

- suffix tree traversal using the suffix links.

Kasai et al. (2001) show how to simulate a bottom-up traversal of the suffix tree using only the suffix array and LCP array. Abouelhoda, Kurtz & Ohlebusch (2004) enhance the suffix array with the LCP array and additional data structures and describe how this enhanced suffix array can be used to simulate all three kinds of suffix tree traversals. Fischer & Heun (2007) reduce the space requirements of the enhanced suffix array by preprocessing the LCP array for range minimum queries. Thus, every problem that can be solved by suffix tree algorithms can also be solved using the enhanced suffix array.[2]

Deciding if a pattern of length is a substring of a string of length takes time if only the suffix array is used. By additionally using the LCP information, this bound can be improved to time.[3] Abouelhoda, Kurtz & Ohlebusch (2004) show how to improve this running time even further to achieve optimal time. Thus, using suffix array and LCP array information, the decision query can be answered as fast as using the suffix tree.

The LCP array is also an essential part of compressed suffix trees which provide full suffix tree functionality like suffix links and lowest common ancestor queries.[5][6] Furthermore, it can be used together with the suffix array to compute the Lempel-Ziv LZ77 factorization in time.[2][7][8][9]

The longest repeated substring problem for a string of length can be solved in time using both the suffix array and the LCP array. It is sufficient to perform a linear scan through the LCP array in order to find its maximum value and the corresponding index where is stored. The longest substring that occurs at least twice is then given by .

The remainder of this section explains two applications of the LCP array in more detail: How the suffix array and the LCP array of a string can be used to construct the corresponding suffix tree and how it is possible to answer LCP queries for arbitrary suffixes using range minimum queries on the LCP array.

Find the number of occurrences of a pattern

In order to find the number of occurrences of a given string (length ) in a text (length ),[3]

- We use binary search against the suffix array of to find the starting and end position of all occurrences of .

- Now to speed up the search, we use LCP array, specifically a special version of the LCP array (LCP-LR below).

The issue with using standard binary search (without the LCP information) is that in each of the comparisons needed to be made, we compare P to the current entry of the suffix array, which means a full string comparison of up to m characters. So the complexity is .

The LCP-LR array helps improve this to , in the following way:

At any point during the binary search algorithm, we consider, as usual, a range of the suffix array and its central point , and decide whether we continue our search in the left sub-range or in the right sub-range . In order to make the decision, we compare to the string at . If is identical to , our search is complete. But if not, we have already compared the first characters of and then decided whether is lexicographically smaller or larger than . Let's assume the outcome is that is larger than . So, in the next step, we consider and a new central point in the middle:

M ...... M' ...... R

|

we know:

lcp(P,M)==k

The trick now is that LCP-LR is precomputed such that an -lookup tells us the longest common prefix of and , .

We already know (from the previous step) that itself has a prefix of characters in common with : . Now there are three possibilities:

- Case 1: , i.e. has fewer prefix characters in common with M than M has in common with M'. This means the (k+1)-th character of M' is the same as that of M, and since P is lexicographically larger than M, it must be lexicographically larger than M', too. So we continue in the right half (M',...,R).

- Case 2: , i.e. has more prefix characters in common with than has in common with . Consequently, if we were to compare to , the common prefix would be smaller than , and would be lexicographically larger than , so, without actually making the comparison, we continue in the left half .

- Case 3: . So M and M' are both identical with in the first characters. To decide whether we continue in the left or right half, it suffices to compare to starting from the th character.

- We continue recursively.

The overall effect is that no character of is compared to any character of the text more than once. The total number of character comparisons is bounded by , so the total complexity is indeed .

We still need to precompute LCP-LR so it is able to tell us in time the lcp between any two entries of the suffix array. We know the standard LCP array gives us the lcp of consecutive entries only, i.e. for any . However, and in the description above are not necessarily consecutive entries.

The key to this is to realize that only certain ranges will ever occur during the binary search: It always starts with and divides that at the center, and then continues either left or right and divide that half again and so forth. Another way of looking at it is : every entry of the suffix array occurs as central point of exactly one possible range during binary search. So there are exactly N distinct ranges that can possibly play a role during binary search, and it suffices to precompute and for those possible ranges. So that is distinct precomputed values, hence LCP-LR is in size.

Moreover, there is a straightforward recursive algorithm to compute the values of LCP-LR in time from the standard LCP array.

To sum up:

- It is possible to compute LCP-LR in time and space from LCP.

- Using LCP-LR during binary search helps accelerate the search procedure from to .

- We can use two binary searches to determine the left and right end of the match range for , and the length of the match range corresponds with the number of occurrences for P.

Suffix tree construction

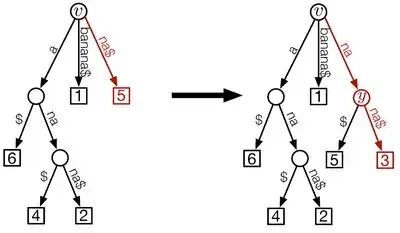

Given the suffix array and the LCP array of a string of length , its suffix tree can be constructed in time based on the following idea: Start with the partial suffix tree for the lexicographically smallest suffix and repeatedly insert the other suffixes in the order given by the suffix array.

Let be the partial suffix tree for . Further let be the length of the concatenation of all path labels from the root of to node .

Start with , the tree consisting only of the root. To insert into , walk up the rightmost path beginning at the recently inserted leaf to the root, until the deepest node with is reached.

We need to distinguish two cases:

- : This means that the concatenation of the labels on the root-to- path equals the longest common prefix of suffixes and .

In this case, insert as a new leaf of node and label the edge with . Thus the edge label consists of the remaining characters of suffix that are not already represented by the concatenation of the labels of the root-to- path.

This creates the partial suffix tree . Case 2 (): In order to add suffix , the edge to the previously inserted suffix has to be split up. The new edge to the new internal node is labeled with the longest common prefix of the suffixes and . The edges connecting the two leaves are labeled with the remaining suffix characters that are not part of the prefix.

Case 2 (): In order to add suffix , the edge to the previously inserted suffix has to be split up. The new edge to the new internal node is labeled with the longest common prefix of the suffixes and . The edges connecting the two leaves are labeled with the remaining suffix characters that are not part of the prefix. - : This means that the concatenation of the labels on the root-to- path displays less characters than the longest common prefix of suffixes and and the missing characters are contained in the edge label of 's rightmost edge. Therefore, we have to split up that edge as follows:

Let be the child of on 's rightmost path.

- Delete the edge .

- Add a new internal node and a new edge with label . The new label consists of the missing characters of the longest common prefix of and . Thus, the concatenation of the labels of the root-to- path now displays the longest common prefix of and .

- Connect to the newly created internal node by an edge that is labeled . The new label consists of the remaining characters of the deleted edge that were not used as the label of edge .

- Add as a new leaf and connect it to the new internal node by an edge that is labeled . Thus the edge label consists of the remaining characters of suffix that are not already represented by the concatenation of the labels of the root-to- path.

- This creates the partial suffix tree .

A simple amortization argument shows that the running time of this algorithm is bounded by :

The nodes that are traversed in step by walking up the rightmost path of (apart from the last node ) are removed from the rightmost path, when is added to the tree as a new leaf. These nodes will never be traversed again for all subsequent steps . Therefore, at most nodes will be traversed in total.

LCP queries for arbitrary suffixes

The LCP array only contains the length of the longest common prefix of every pair of consecutive suffixes in the suffix array . However, with the help of the inverse suffix array (, i.e. the suffix that starts at position in is stored in position in ) and constant-time range minimum queries on , it is possible to determine the length of the longest common prefix of arbitrary suffixes in time.

Because of the lexicographic order of the suffix array, every common prefix of the suffixes and has to be a common prefix of all suffixes between 's position in the suffix array and 's position in the suffix array . Therefore, the length of the longest prefix that is shared by all of these suffixes is the minimum value in the interval . This value can be found in constant time if is preprocessed for range minimum queries.

Thus given a string of length and two arbitrary positions in the string with , the length of the longest common prefix of the suffixes and can be computed as follows: .

Notes

References

- Abouelhoda, Mohamed Ibrahim; Kurtz, Stefan; Ohlebusch, Enno (2004). "Replacing suffix trees with enhanced suffix arrays". Journal of Discrete Algorithms. 2: 53–86. doi:10.1016/S1570-8667(03)00065-0.

- Manber, Udi; Myers, Gene (1993). "Suffix Arrays: A New Method for On-Line String Searches". SIAM Journal on Computing. 22 (5): 935. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.105.6571. doi:10.1137/0222058. S2CID 5074629.

- Kasai, T.; Lee, G.; Arimura, H.; Arikawa, S.; Park, K. (2001). Linear-Time Longest-Common-Prefix Computation in Suffix Arrays and Its Applications. Proceedings of the 12th Annual Symposium on Combinatorial Pattern Matching. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2089. pp. 181–192. doi:10.1007/3-540-48194-X_17. ISBN 978-3-540-42271-6.

- Ohlebusch, Enno; Fischer, Johannes; Gog, Simon (2010). CST++. String Processing and Information Retrieval. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 6393. p. 322. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-16321-0_34. ISBN 978-3-642-16320-3.

- Kärkkäinen, Juha; Sanders, Peter (2003). Simple linear work suffix array construction. Proceedings of the 30th international conference on Automata, languages and programming. pp. 943–955. Retrieved 2012-08-28.

- Fischer, Johannes (2011). Inducing the LCP-Array. Algorithms and Data Structures. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 6844. pp. 374–385. arXiv:1101.3448. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-22300-6_32. ISBN 978-3-642-22299-3.

- Manzini, Giovanni (2004). Two Space Saving Tricks for Linear Time LCP Array Computation. Algorithm Theory – SWAT 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3111. p. 372. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-27810-8_32. ISBN 978-3-540-22339-9.

- Kärkkäinen, Juha; Manzini, Giovanni; Puglisi, Simon J. (2009). Permuted Longest-Common-Prefix Array. Combinatorial Pattern Matching. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5577. p. 181. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-02441-2_17. ISBN 978-3-642-02440-5.

- Puglisi, Simon J.; Turpin, Andrew (2008). Space-Time Tradeoffs for Longest-Common-Prefix Array Computation. Algorithms and Computation. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5369. p. 124. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-92182-0_14. ISBN 978-3-540-92181-3.

- Gog, Simon; Ohlebusch, Enno (2011). Fast and Lightweight LCP-Array Construction Algorithms (PDF). Proceedings of the Workshop on Algorithm Engineering and Experiments, ALENEX 2011. pp. 25–34. Retrieved 2012-08-28.

- Nong, Ge; Zhang, Sen; Chan, Wai Hong (2009). Linear Suffix Array Construction by Almost Pure Induced-Sorting. 2009 Data Compression Conference. p. 193. doi:10.1109/DCC.2009.42. ISBN 978-0-7695-3592-0.

- Fischer, Johannes; Heun, Volker (2007). A New Succinct Representation of RMQ-Information and Improvements in the Enhanced Suffix Array. Combinatorics, Algorithms, Probabilistic and Experimental Methodologies. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 4614. p. 459. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74450-4_41. ISBN 978-3-540-74449-8.

- Chen, G.; Puglisi, S. J.; Smyth, W. F. (2008). "Lempel–Ziv Factorization Using Less Time & Space". Mathematics in Computer Science. 1 (4): 605. doi:10.1007/s11786-007-0024-4. S2CID 1721891.

- Crochemore, M.; Ilie, L. (2008). "Computing Longest Previous Factor in linear time and applications". Information Processing Letters. 106 (2): 75. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.70.5720. doi:10.1016/j.ipl.2007.10.006. S2CID 5492217.

- Crochemore, M.; Ilie, L.; Smyth, W. F. (2008). A Simple Algorithm for Computing the Lempel Ziv Factorization. Data Compression Conference (dcc 2008). p. 482. doi:10.1109/DCC.2008.36. hdl:20.500.11937/5907. ISBN 978-0-7695-3121-2.

- Sadakane, K. (2007). "Compressed Suffix Trees with Full Functionality". Theory of Computing Systems. 41 (4): 589–607. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.224.4152. doi:10.1007/s00224-006-1198-x. S2CID 263130.

- Fischer, Johannes; Mäkinen, Veli; Navarro, Gonzalo (2009). "Faster entropy-bounded compressed suffix trees". Theoretical Computer Science. 410 (51): 5354. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2009.09.012.

- Fischer, Johannes; Kurpicz, Florian (5 October 2017). "Dismantling DivSufSort". Proceedings of the Prague Stringology Conference 2017. arXiv:1710.01896.

External links

- Mirror of the ad-hoc-implementation of the code described in Fischer (2011)

- SDSL: Succinct Data Structure Library - Provides various LCP array implementations, Range Minimum Query (RMQ) support structures and many more succinct data structures

- Bottom-up suffix tree traversal emulated using suffix array and LCP array (Java)

- Text-Indexing project (linear-time construction of suffix trees, suffix arrays, LCP array and Burrows–Wheeler Transform)