Lace machines took over the commercial manufacture of lace during the nineteenth century.

History

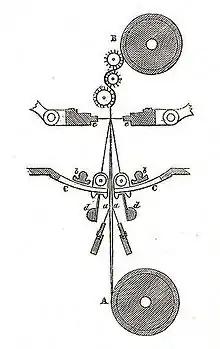

The stocking frame was a mechanical weft-knitting knitting machine used in the textile industry. It was invented by William Lee of Calverton near Nottingham in 1589. Framework knitting, was the first major stage in the mechanisation of the textile industry at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. It was adapted to knit cotton, do ribbing and by 1800, with the introduction of dividers (divider bar) as a lace making machine.

Bobbinet machines were invented in 1808 by John Heathcoat. He studied the hand movements of a Northamptonshire manual lace maker and reproduced them in the roller-locker machine. The 1809 version of this machine (patent no. 3216) became known as the Old Loughborough, it was 18 inches (46 cm) wide and was designed for use with cotton.[1]

The Old Loughborough became the standard lacemaking machine, particularly the 1820 form known as the Circular producing two-twist plain net. The smooth, unpatterned tulle produced on these machines was on a par with real, handmade lace net. Heathcoat's bobbinet machine is so ingeniously designed that the ones used today have suffered little alteration.[2] However during the next 30 years inventors were patenting improvements to their machines. The ones that stand out are the Pusher machine, the Levers machine (now spelled Leavers) and the Nottingham lace curtain machine. Each of these developed into separate machines. Others were the Traverse Warp machine and the Straight Bolt machine.[2]

Time line

- 1589 – William Lee of Calverton, a village some 7 miles from Nottingham, invented the stocking frame

- 1768 – Josiah Crane invents the hand-operated warp knitting machine.

- 1791 – The Englishman Dawson solves the mechanization of the warp knitting machine.

- 1801 – Joseph Marie Jacquard invents the Jacquard punched card loom.

- 1808 – John Heathcoat patented the bobbin net machine in Loughborough

- 1813 – John Levers adapted Heathcoat's machine in Nottingham producing the Leavers machine (sic), which could work with a Jacquard head.

- 1835 – general application of pierced bars and the Jacquard apparatus [3]

- 1846 – John Livesey, in Nottingham, adapts John Heathcoat's bobbinet machine into the curtain machine

- 1855 – Redgate combines a circular loom with a warp knitting machine

- 1859 – Wilhelm Barfuss improves on Redgate's machine, called Raschel machines (named after the French actress Élisabeth Félice Rachel).

- 1890s – Development of the Barmen machine

Typology

Stocking frame

The stocking frame, invented in 1589 by Lee, consisted of a stout wooden frame. It did straight knitting not tubular knitting. It had a separate needle for each loop- these were low carbon steel bearded needles where the tips were reflexed and could be depressed onto a hollow closing the loop. The needle were supported on a needle bar that passed back and forth, to and from the operator. The beards were simultaneously depressed by a presser bar. The first machine had 8 needles per inch and was suitable for worsted: The next version had 16 needles per inch and was suitable for silk.[4]

Warp frame

This includes the later Raschel machine

Bobbinet

The bobbinet machine, invented by John Heathcoat in Loughborough, Leicestershire, in 1808,[5] makes a perfect copy of Lille or East Midlands net (fond simple, a six-sided net with four sides twisted, two crossed). The machine uses flat round bobbins in carriages to pass through and round vertical threads.[6]

Pusher

In 1812 Samuel Clark and James Mart constructed a machine that was capable of working a pattern and net at the same time. A pusher operated each bobbin and carriage independently allowing almost unlimited designs and styles. The machine however was slow, delicate, costly and could produce only short "webs" of about two by four yards.[7] The machine was modified by J. Synyer in 1829.[8] and by others before. Production had its heydays in the 1860s and ceased around 1870–1880.[9]

Leavers

John Levers adapted Heathcoat's Old Loughborough machine while working in a garret on Derby Road Nottingham in 1813. The name of the machine was the Leavers machine (the 'a' was added to aid pronunciation in France). The original machine made net but it was discovered that the Jacquard apparatus (invented in France for weaving looms by J M Jacquard in about 1800) could be adapted to it. From 1841 lace complete with pattern, net and outline could be made on the Leavers machine. The Leavers machine is probably the most versatile of all machines for making patterned lace.[6][10]

Nottingham lace curtain machine

The lace curtain machine, invented by John Livesey in Nottingham in 1846 was another adaptation of John Heathcoat's bobbinet machine. It made the miles of curtaining which screened Victorian and later windows.[6]

Barmen

The Barmen machine was developed in the 1890s in Germany from a braiding machine. Its bobbins imitate the movements of the bobbins of the hand-made lace maker and it makes perfect copies of Torchon and the simpler hand-made laces.[6] It can only make one width at a time, and has a maximum width of about 120 threads.[11]

Embroidery machines

These produce Chemical lace or Burnt out lace on bobbinet or dissolvable net,[12] For instance the Heilmann of 1828, Multihead, Bonnaz, Cornely and the Schiffli embroidery machine.[13]

Social effects

Part laces like Honiton and Brussels profited to a certain degree from mechanisation. [14] Part lace is made in pieces or motifs, which are joined together on a ground, net or mesh, or with plaits, bars or legs.[15] With mechanisation, the complex motifs could be mounted on machine made net. New net based laces emerged, such as Carrickmacross and Tambour lace.[16]

By 1870, virtually every type of hand-made lace (pillow lace, bobbin lace) had its machine-made copy. It became increasingly difficult for hand lacemakers to make a living from their work and most of the English handmade lace industry had disappeared by 1900.[17]

Few were interested in tracing and curating old laces and few courses were available to keep the technique alive, until a revival in the 1960s.[18]

References

Notes

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, p. 67.

- 1 2 Earnshaw 1986, p. 96.

- ↑ Felkin 1867, p. 356.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, pp. 12, 13.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Farrell 2007.

- ↑ Mahin, Abbie C. "Pusher Lace: An Early American Machine-Made Fabric" (PDF). The Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club. 6 (1922): 5. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ↑ Felkin 1867, p. 293.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, pp. 107–172.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, pp. 202–225.

- ↑ Farrell 2007, p. 22.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, pp. 226–260.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, p. 135.

- ↑ Rosemary Shepherd. "Lace Classification System" (PDF). Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, pp. 127, 132.

- ↑ "The Craft of Lacemaking". LaceGuild.org. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, p. 24.

Bibliography

- Earnshaw, Pat (1985). The Identification of lace. De Bild:Cantecleer. ISBN 9021302179.

- Earnshaw, Pat (1986). Lace Machines and Machine Laces. Batsford. ISBN 0713446846.

- Farrell, Jeremy (2007). "Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace" (PDF). DATS (Dress and Textile Specialists) in partnership with the V&A.

- Felkin, William. A history of the machine-wrought hosiery and lace manufacturies. Longmans, G.Keen, and co. 1867.

- Rosatto, Vittoria (1948). Leavers Lace:A Handbook of the American Leavers Lace Industry (PDF). Providence, RI: American Lace Manufacturers Association. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

External links

Media related to Lacemaking machines at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lacemaking machines at Wikimedia Commons