Shown within Iraq | |

| Location | Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 30°48′57″N 45°59′46″E / 30.81583°N 45.99611°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | At most 10 ha (25 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 5400 BC |

| Abandoned | c. 600 BC |

| Periods | Ubaid, Early Dynastic, Ur III, Old Babylonian, Kassite, Neo-Babylonian |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1855, 1918-1919, 1946-1949, 2018 |

| Archaeologists | John George Taylor, R. Campbell Thompson, H. R. Hall, Fuad Safar, Seton Lloyd, Franco D’Agostino |

| Official name | Tell Eridu Archaeological Site |

| Part of | Ahwar of Southern Iraq |

| Criteria | Mixed: (iii)(v)(ix)(x) |

| Reference | 1481-007 |

| Inscription | 2016 (40th Session) |

| Area | 33 ha (0.13 sq mi) |

| Buffer zone | 1,069 ha (4.13 sq mi) |

| Coordinates | 30°49′1″N 45°59′45″E / 30.81694°N 45.99583°E |

Eridu (Cuneiform: NUN.KI 𒉣𒆠; Sumerian: eridugki; Akkadian: irîtu) was a Sumerian city located at Tell Abu Shahrain (Arabic: تل أبو شهرين), also Abu Shahrein or Tell Abu Shahrayn, an archaeological site in southern Mesopotamia. It is located in Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq near the modern city of Basra. Eridu is traditionally believed to be the earliest city in southern Mesopotamia based on the Sumerian King List. Located 12 kilometers southwest of the ancient site of Ur, Eridu was the southernmost of a conglomeration of Sumerian cities that grew around temples, almost in sight of one another. The city gods of Eridu were Enki and his consort Damkina. Enki, later known as Ea, was considered to have founded the city. His temple was called E-Abzu, as Enki was believed to live in Abzu, an aquifer from which all life was believed to stem. According to Sumerian temple hymns another name for the temple of Ea/Enki was called Esira (Esirra).

"... The temple is constructed with gold and lapis lazuli, Its foundation on the nether-sea (apsu) is filled in. By the river of Sippar (Euphrates) it stands. O Apsu pure place of propriety, Esira, may thy king stand within thee. ..."[1][2]

At nearby Ur there was a temple of Ishtar of Eridu (built by Lagash ruler Ur-Baba) and a sanctuary of Inanna of Eridu (built by Ur III ruler Ur-Nammu). Ur-Nammu also recorded building a temple of Ishtar of Eridu at Ur which is assumed to have been a rebuild.[3][4]

One of the religious quarters of Babylon, containing the Esagil temple and the temple of Annunitum among others, was also named Eridu.[5]

History

Eridu is one of the earliest settlements in the region, founded c. 5400 BC during the Early Ubaid period, at that time close to the Persian Gulf near the mouth of the Euphrates River though in modern times about 90 miles inland. Excavation has shown that the city was founded on a virgin sand-dune site with no previous habitation. With possible breaks in occupation in the Early Dynastic III and Akkadian Empire periods the city was inhabited up to the Neo-Babylonian though in later times it was primarily a cultic site. According to the excavators, construction of the Ur III ziggurat and associated buildings was preceded by the destruction of preceding construction and its use as leveling fill so no remains from that time were found. At a small mound 1 kilometer north of Eridu two Early Dynastic III palaces were found, with an enclosure wall. The palaces measured 45 meters by 65 meters with 2.6 meter wide walls and were constructed in the standard Early Dynastic period method of plano-convex bricks laid in a herringbone fashion.[6]

During the Ubaid period the site extended out to an area of about 12 hectares (about 30 acres). Twelve neolithic clay tokens, the precursor to Proto-cuneiform, were found in the Ubaid levels of the site.[7][8] Eighteen superimposed mudbrick temples at the site underlie the unfinished Ziggurat of Amar-Sin (c. 2047–2039 BC). Levels XIX to VI were from the Ubaid period and Levels V to I were dated to the Uruk period.[9] Significant habitation was found from the Uruk period with "non-secular" buildings being found in soundings. Uruk finds included decorative terracotta cones topped with copper, copper nails topped with gold, a pair of basalt stone lion statues, columns several meters in diameter coated with cones and gypsum, and extensive Uruk period pottery.[10][11][12][13] Occupation increased in the Early Dynastic period with a monumental 100 meter by 100 meter palace being constructed.[14] An inscription of Elulu, a ruler of the 1st Dynasty of Ur (c. 2600 BC) was found at Eridu.[15] On a statue of Early Dynastic ruler of Lagash, Enmetena (c. 2400 BC), it reads "... he built Ab-zupasira for Enki, king of Eridu ...",[16]

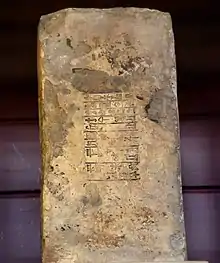

Eridu was active during the Ur III dynasty (22nd to 21st century BC) and royal building activity is known from inscribed bricks notably those of Ur-Nammu from his ziggurat marked "Ur-Nammu, king of Ur, the one who built the temple of the god Enki in Eridu.".[17] Three Ur III rulers designated Year Names based on the appointment of an en-priestess (high priestess) of the temple of Enki in Eridu, the highest religious office in the land at that time. In each the first two cases it was also used as the succeeding Year Name.

- Sulgi Year 28 - "Year the szita-priest-who-intercedes-for-Szulgi, the son of Szulgi, the strong man, the king of Ur, the king of the four corners of the universe, was installed as en-priest of Enki in Eridu"

- Amar-Sin Year 8 - "Year (Ennune-kiag-Amar-Sin) Ennune-the beloved (of Amar-Sin, was installed as en-priestess of Enki in Eridu)"

- Ibbi-Sin Year 11 - "Year the szita-priest who prays piously for Ibbi-Sin was chosen by means of the omens as en-priest of Enki in Eridu"

After the fall of Ur III the site was occupied and active during the Isin-Larsa period (early 2nd Millennium BC) as evidenced by a Year Name of Nur-Adad, ruler of Larsa "Year the temple of Enki in Eridu was built" and texts of Larsa rulers Ishbi-Erra and Ishme-Dagan showing control over Eridu.[18] Inscribed construction bricks of Nur-Adad have also been found at Eridu.[19] This continued in the Old Babylonian period with Hammurabi stating in his 33rd Year Name "Year Hammu-rabi the king dug the canal (called) 'Hammu-rabi is abundance to the people', the beloved of An and Enlil, established the everlasting waters of plentifulness for Nippur, Eridu, Ur, Larsa, Uruk and Isin, restored Sumer and Akkad which had been scattered, overthrew in battle the army of Mari and Malgium and caused Mari and its territory and the various cities of Subartu to dwell under his authority in friendship"

In an inscription of Kurigalzu I (c. 1375 BC), a ruler of the Kassite dynasty one of his epitaphs is "[he one who ke]eps the sanctuary in Eridu in order".[20]

An inscription of the 2nd dynasty of Sealand ruler Simbar-shipak (c. 1021–1004 BC) mentions a priest of Eridu.[21]

The Neo-Assyrian ruler Sargon II (722–705 BC) awarded andurāru-status (described as "a periodic reinstatement of goods and persons, alienated because of want, to their original status") to Eridu.[22]

The Neo-Babylonian ruler Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BC) built at Eridu as evidenced by inscribed bricks found there.[23]

Archaeology

Eridu is located on a natural hill in a basin approximately 15 miles long and 20 feet deep, which is separated from the Euphrates by a sandstone ridge called the Hazem.[24] This basin, the As Sulaybiyat Depression (formerly: Khor en-Nejeif), becomes a seasonal lake (Arabic: Sebkha) during the rainy season from November to April.[25] During this period, it is filled by the discharge of the Wadi Khanega. Adjacent to eastern edge of the seasonal lake are the Hammar Marshes.

In the 3rd Millennium BC a canal, Id-edin-Eriduga (NUN)ki "the canal of the Eridug plain", connected Eridu to the Euphrates river, which later shifted its course. The path of the canal is marked by several low tells with 2nd Millennium BC surface pottery and later burials.[26]

The site contains 8 mounds:[27]

- Mound 1 - Abū Šahrain, 580 meters x 540 meters in area NW to WE, 25 meters in height, Enki Temple, Ur III Ziggurat (É-u6-nir) Sacred Area, Early Dynastic plano-convex bricks found, Ubaid Period cemetery

- Mound 2 - 350 meters x 350 meters in area, 4.3 meters in height, 1 kilometer N of Abū Šahrain, Early Dynastic Palace, remnants of city wall built with plano-convex bricks

- Mound 3 - 300 × 150 meters in area, 2.5 meters high, 2.2 kilometers SSW of Abū Šahrain, Isin-Larsa pottery found

- Mound 4 - 600 × 300 meters in area, 2.5 kilometers SW of Abū Šahrain, Kassite pottery found

- Mound 5 - 500 × 300 meters in area, 3 meters high, 1.5 kilometers SE of Abū Šahrain, Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid periods

- Mound 6 - 300 × 200 meters in area, 2 meters high, 2.5 kilometers SW of Abū Šahrain

- Mound 7 - 400 × 200 meters in area, 1.5 meters high, 3 kilometers E of Abū Šahrai

- Mound 8 - Usalla, flat area, 8 kilometers NW of Abū Šahrain, Hajj Mohammed and later Ubaid

The site was initially excavated by John George Taylor, the British Vice-counsel at Basra, in 1855.[24] Among the finds were inscribed bricks enabling the identification of the site as Eridu.[28] Excavation on the main tell next occurred by R. Campbell Thompson in 1918, and H. R. Hall in 1919, who also conducted a survey in the area around the tell.[29][30][31][32][33][34] An interesting find by Hall was a piece of manufactured blue glass which he dated to c. 2000 BC. The blue color was achieved with cobalt, long before this technique emerged in Egypt.[35]

Excavation there resumed from 1946 to 1949 under Fuad Safar and Seton Lloyd of the Iraqi Directorate General of Antiquities and Heritage. Among the finds were a Ubaid period terracotta boat model, complete with a socket amidship for a mast and hole for stays and rudder and a "lizard type" figurine like those found in a sounding under the Royal Cemetery of Ur. Soundings in the cemetery showed it to have about 1000 graves, all from the end of the Ubaid period (Temple levels VI and VII).[6][36][37][38][39] They found a sequence of 17 Ubaid Period superseding temples and an Ubaid Period graveyard with 1000 graves of mud-brick boxes oriented to the southeast. The temple began as a 2 meter by 3 meter mud brick square with a niche. At Level XI it was rebuilt and eventually reached its final tripartite form in Level VI. In Ur III times a 300 square meter platform was constructed as a base for a ziggurat.[40] These archaeological investigations showed that, according to A. Leo Oppenheim, "eventually the entire south lapsed into stagnation, abandoning the political initiative to the rulers of the northern cities", probably as a result of increasing salinity produced by continuous irrigation, and the city was abandoned in 600 BC.[41] In 1990 the site was visited by A. M. T. Moore who found two areas of surface pottery kilns not noted by the earlier excavators.[42]

In October 2014 Franco D’Agostino visited the site in preparation for the coming resumption of excavation, noting a number of inscribed Amar-Sin brick fragments on the surface.[43] In 2019, excavations at Eridu were resumed by a joint Italian, French, and Iraqi effort which included the University of Rome La Sapienza and the University of Strasbourg.[44][45][46]

Tablet controversy

._From_Eridu_(Tell_Abu_Shahrain)%252C_Iraq._3500-2800_BCE._Iraq_Museum%252C_Baghdad.jpg.webp)

In March 2006, Giovanni Pettinato and S. Chiod from Rome's La Sapienza University claimed to have discovered 500 Early Dynastic historical and literary cuneiform tablets on the surface at Eridu "disturbed by an explosion". The tablets were said to be from 2600 to 2100 BC (rulers Eannatum to Amar-Sin) and be part of a library. A team was sent to the site by Iraq's State Board of Antiquities and Heritage which found no tablets, only stamped bricks from Eridu and surrounding sites such as Ur. Nor was there a permit to excavate at the site issued to anyone.[47][48] At this point Pettinato stated that they had actually found 70 inscribed bricks. This turned out to be stamped bricks used to build the modern Eridu dig-house. The dig-house had been built using bricks from the demolished Leonard Woolley’s expedition house at Ur (clearly spelled out in the 1981 Iraqi excavation report to avoid confusion to future archaeologists.[49]

Myth and legend

.jpg.webp)

In some, but not all, versions of the Sumerian King List, Eridu is the first of five cities where kingship was received before a flood came over the land. The list mentions two rulers of Eridu from the Early Dynastic period, Alulim and Alalngar.[50][51]

[nam]-lugal an-ta èd-dè-a-ba |

When kingship from heaven was lowered, |

The bright star Canopus was known to the ancient Mesopotamians and represented the city of Eridu in the Three Stars Each Babylonian star catalogues and later around 1100 BC on the MUL.APIN tablets.[53] Canopus was called MUL.NUNKI by the Babylonians, which translates as "star of the city of Eridu". From most southern city of Mesopotamia, Eridu, there is a good view to the south, so that about 6000 years ago due to the precession of the Earth's axis the first rising of the star Canopus in Mesopotamia could be observed only from there at the southern meridian at midnight. In the city of Ur this was the case only 60 years later.[54]

In the flood myth tablet[55] found in Ur, how Eridu and Alulim were chosen by gods as first city and first priest-king is described in more detail. The following is the English translation of the tablet:[56]

(Obverse) |

(Reverse) |

Adapa, a man of Eridu, is depicted as an early culture hero. Although earlier tradition, Me-Turan/Tell-Haddad tablet, describes Adapa as postdiluvian ruler of Eridu,[57] in late tradition, Adapa came to be viewed as Alulim’s vizier,[58] and he was considered to have brought civilization to the city as the sage of King Alulim.[59][60]

.jpg.webp)

In Sumerian mythology, Eridu was the home of the Abzu temple of the god Enki, the Sumerian counterpart of the Akkadian god Ea, god of deep waters, wisdom and magic. Like all the Sumerian and Babylonian gods, Enki/Ea began as a local god who, according to the later cosmology, came to share the rule of the cosmos with Anu and Enlil. His kingdom was the sweet waters that lay below earth (Sumerian ab=water; zu=far).[61]

The stories of Inanna, goddess of Uruk, describe how she had to go to Eridu in order to receive the gifts of civilization. At first Enki, the god of Eridu, attempted to retrieve these sources of his power but later willingly accepted that Uruk now was the centre of the land.[62][63]

The fall of early Mesopotamia cities and empires was typically believed to be the result of falling out of favor with the gods. A genre called City Laments developed during the Isin-Larsa period, of which the Lament for Ur is the most famous. These laments had a number of sections (kirugu) of which only fragments have been recovered. The Lament for Eridu describes the fall of that city.[64][65]

"Its king stayed outside his city as if it were an alien city. He wept bitter tears. Father Enki stayed outside his city as if it were an alien city. He wept bitter tears. For the sake of his harmed city, he wept bitter tears. Its lady, like a flying bird, left her city. The mother of E-maḫ, holy Damgalnuna, left her city. The divine powers of the city of holiest divine powers were overturned. The divine powers of the rites of the greatest divine powers were altered. In Eridug everything was reduced to ruin, was wrought with confusion."[66]

Architecture

The urban nucleus of Eridu was Enki's temple, called House of the Aquifer (Cuneiform: 𒂍𒍪 𒀊, E2.ZU.AB; Sumerian: e2-abzu; Akkadian: bītu apsû), which in later history was called House of the Waters (Cuneiform: 𒂍𒇉, E2.LAGAB×HAL; Sumerian: e2-engur; Akkadian: bītu engurru). The name refers to Enki's realm.[67] His consort Ninhursag had a nearby temple at Ubaid.[68]

During the Ur III period Ur-Nammu had a ziggurat built over the remains of previous temples.

Aside from Enmerkar of Uruk (as mentioned in the Aratta epics), several later historical Sumerian kings are said in inscriptions found here to have worked on or renewed the e-abzu temple, including Elili of Ur; Ur-Nammu, Shulgi and Amar-Sin of Ur-III, and Nur-Adad of Larsa.[69][70]

House of the Aquifer (E-Abzu)

| Level | Date (BC) | Period | Size (m) | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XVIII | 5300 | - | 3×0.3 | Sleeper walls |

| XVII | 5300–5000 | - | 2.8×2.8 | First cella |

| XVI | 5300–4500 | Early Ubaid | 3.5×3.5 | |

| XV | 5000–4500 | Early Ubaid | 7.3×8.4 | |

| XIV | 5000–4500 | Early Ubaid | - | No structure found |

| XIII | 5000–4500 | Early Ubaid | - | No structure found |

| XII | 5000–4500 | Early Ubaid | - | No structure found |

| XI | 4500–4000 | Ubaid | 4.5×12.6 | First platform |

| X | 4500–4000 | Ubaid | 5×13 | |

| IX | 4500–4000 | Ubaid | 4×10 | |

| VIII | 4500–4000 | Ubaid | 18×11 | |

| VII | 4000–3800 | Ubaid | 17×12 | |

| VI | 4000–3800 | Ubaid | 22×9 | |

| V | 3800–3500 | Early Uruk | - | Only platform remains |

| IV | 3800–3500 | Early Uruk | - | Only platform remains |

| III | 3800–3500 | Early Uruk | - | Only platform remains |

| II | 3500–3200 | Early Uruk | - | Only platform remains |

| I | 3200 | Early Uruk | - | Only platform remains |

See also

References

- ↑ Langdon, Review of "Campbell Thompson, R 'The British Museum excavations at Abu Shahrain in Mesopotamia in 1918', 1920", S. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, no. 4, pp. 621–25, 1922

- ↑ Langdon, S., "Two Sumerian Hymns from Eridu and Nippur", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 161–86, 1923

- ↑ Clayden, Tim, "Kassite housing at Ur: the dates of the EM, YC, XNCF, AH and KPS houses", Iraq, vol. 76, pp. 19–64, 2014

- ↑ Radau, Hugo, "Letters to Cassite Kings from the Temple Archives of Nippur", Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1908

- ↑ Gurney, O. R., "The Fifth Tablet of ‘The Topography of Babylon’", Iraq, vol. 36, no. 1/2, pp. 39–52, 1974

- 1 2 al Asil, Naji and Lloyd, Seton and Safar, Fuad, "Eridu", Sumer, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 84–111, July 1947

- ↑ Overmann, Karenleigh A., "The Neolithic Clay Tokens", The Material Origin of Numbers: Insights from the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 157-178, 2019

- ↑ Wright, H. T., "Appendix: The Southern Margins of Sumer. Archaeological Survey of the Area of Eridu and Ur", In: R. M. Adams (ed.), The Heartland of Cities: Survey of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Flood Plain of the Euphrates (Chicago-London), pp. 295–345, 1981

- ↑ Quenet, Philippe, "Eridu: Note on the Decoration of the Uruk ‘Temples.’", Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East: Vol. 2: Field Reports. Islamic Archaeology, edited by Adelheid Otto et al., 1st ed., Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 341–48, 2020

- ↑ Lloyd, S., "Uruk Pottery: A Comparative Study in relation to recent Finds at Eridu", Sumer, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 39–51, 1948

- ↑ Van Buren, E. Douglas, "Excavations at Eridu", Orientalia, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 115–19, 1948

- ↑ Becker, A., "Uruk Kleinfunde I", Stein. Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka Endberichte 6, Mainz, 1993

- ↑ al-Soof A.B., "Uruk Pottery from Eridu, Ur, and al-Ubaid", Sumer, vol. 20, no. 1-2, pp. 17–22, 1973

- ↑ Adams, Robert McCormick, "The Evolution of Urban Society: Early Mesopotamia and Prehistoric Mexico", Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966

- ↑ Sollberger, Edmond, and Jean-Robert Kupper, "Inscriptions royales sumeriennese akkadiennes", Littératures Anciennes du Proche-Orient 3, Paris: Les Éditions du Cerf, 1971

- ↑ Schmandt-Besserat, Denise, "Six Votive and Dedicatory Inscriptions", When Writing Met Art: From Symbol to Story, New York, USA: University of Texas Press, pp. 71-86, 2007

- ↑ Frayne, Douglas, "Ur-Nammu E3/2.1.1", Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 5-90, 1997

- ↑ De Graef, Katrien. "Bad Moon Rising: The Changing Fortunes of Early Second-Millennium BCE Ur", Ur in the Twenty-First Century CE: Proceedings of the 62nd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Philadelåpåphia, July 11–15, 2016, edited by Grant Frame, Joshua Jeffers and Holly Pittman, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 49-88, 2021

- ↑ “RIME 4.02.08.05, Ex. 01 Artifact Entry.” (2006) 2023. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). June 15, 2023. https://cdli.ucla.edu/P345487.

- ↑ Oshima, Takayoshi, "Another Attempt at Two Kassite Royal Inscriptions: The Agum-Kakrime Inscription and the Inscription of Kurigalzu the Son of Kadashmanharbe", Babel und Bibel 6, edited by Leonid E. Kogan, N. Koslova, S. Loesov and S. Tishchenko, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 225-268, 2012

- ↑ L.W. King, "Babylonian Boundary Stones and Memorial Tablets in the British Museum (BBSt)", London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1912

- ↑ Frazer, Mary and Adalı, Selim Ferruh, "“The just judgements that Ḫammu-rāpi, a former king, rendered”: A New Royal Inscription in the Istanbul Archaeological Museums", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 111, no. 2, pp. 231-262, 2021

- ↑ BMHBA 94, 17 05 artifact entry (No. P283716). (2005, November 15). Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). https://cdli.ucla.edu/P283716

- 1 2 J. E. Taylor, "Notes on Abu Shahrein and Tell el Lahm", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 15, pp. 404–415, 1855

- ↑ Edwards, I. E.S. (ed.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. I, Part 1: Prolegomena and Prehistory (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 331-332. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ↑ Thorkild Jacobsen, "The Waters of Ur", Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture, Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, pp. 231-244, 1970

- ↑ Safar, Fuad et al., "Eridu", Baghdad: Ministry of Culture and Information, 1981

- ↑ Hilprecht, H. V., "First Successful Attempts In Babylonia", Explorations in Bible Lands During the 19th Century, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 138-186, 2004

- ↑ Hall, H. R., "Recent Excavations of the British Museum at Tell el-Mukayyar (Ur ‘of the Chaldees’), Tell Abu Shahrein (Eridu), and Tell el-Ma‘abed or Tell el-‘Obeid, near Ur", Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries 32, pp. 22–44, 1920

- ↑ Campbell Thompson, "The British Museum Excavations at Abu Shahrain in Mesopotamia in 1918", Archaeologia 70, pp. 101-44, 1920

- ↑ H. R. Hall, "Notes on the Excavations of 1919 at Muqayyar, el-‘Obeid, and Abu Shahrein", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 56, Centenary Supplement, pp. 103–115, 1924

- ↑ Hall, H. R., "The Excavations of 1919 at Ur, el-’Obeid, and Eridu, and the History of Early Babylonia", Man 25, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, pp. 1–7, 1925

- ↑ Hall, H. R., "Ur and Eridu: The British Museum Excavations of 1919", The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 9, pp. 177–95, 1923

- ↑ Hall, H.R., "A Season's Work at Ur,Al-ʻUbaid, Abu Shahrain (Eridu) and Elsewhere. Being an Unofficial Account of the British Museum Archaeological Mission to Babylonia, 1919", London, 1930

- ↑ Garner, Harry, "An Early Piece of Glass from Eridu", Iraq, vol. 18, no. 2, 1956, pp. 147–49, 1956 doi:10.2307/4199608

- ↑ Lloyd, Seton and Safar, Fuad, "Eridu. A Preliminary Communication on the Second Season’s Excavations. 1947-1948.", Sumer, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 115–127, September 1948

- ↑ Fuad Safar, "The Third Season's Excavation at Eridu", Sumer, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 159–174, 1949 (In Arabic.)

- ↑ Fuad Safar, "ERIDU A Preliminary Report on the Third Season's Excavation at Eridu, 1948-1949", Sumer, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 27–38, 1950

- ↑ Lloyd, Seton, "Abu Shahrein: A Memorandum", Iraq 36, pp. 129–38, 1974

- ↑ Laneri, Nicola, "From High to Low: Reflections about the Emplacement of Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia", Naming and Mapping the Gods in the Ancient Mediterranean: Spaces, Mobilities, Imaginaries, edited by Corinne Bonnet, Thomas Galoppin, Elodie Guillon, Max Luaces, Asuman Lätzer-Lasar, Sylvain Lebreton, Fabio Porzia, Jörg Rüpke and Emiliano Rubens Urciuoli, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 371-386, 2022

- ↑ A. Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964, revised in 1977

- ↑ Moore, A. M. T., "Pottery Kiln Sites at al ’Ubaid and Eridu", Iraq, vol. 64, pp. 69–77, 2002, doi:10.2307/4200519

- ↑ D’Agostino, Franco, "The Eridu Project (AMEr) and a Singular Brick-Inscription of Amar- Suena from Abū Šahrain", The First Ninety Years: A Sumerian Celebration in Honor of Miguel Civil, edited by Lluís Feliu, Fumi Karahashi and Gonzalo Rubio, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 70–79, 2017

- ↑ Franco D'Agostino, Anne-Caroline Rendu Loisel, and Philippe Quénet, The first campaign at Eridu, April 2019 (Project AMEr), pp. 65–90, Rivista degli studi orientali : XCIII, 1/2, 2020

- ↑ Ramazzotti, Marco, "The Iraqi-Italian Archaeological Mission at The Seven Mounds of Eridu (AMEr)", The Iraqi-Italian Archaeological Mission at The Seven Mounds of Eridu (AMEr), pp. 3-29, 2015

- ↑ Rendu Loisel, Anne-Caroline. "Another brick (-stamp) in the wall: few remarks on Amar-Suena's bricks in Eridu", Oriens antiquus : rivista di studi sul Vicino Oriente Antico e il Mediterraneo orientale : II, pp. 81-98, 2020

- ↑ Biggin, S.; Lawler, A. (10 April 2006). "Iraq Antiquities Find Sparks Controversy". Science. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ↑ Curtis, John et al., "An Assessment of Archaeological Sites in June 2008: An Iraqi-British Project", Iraq, vol. 70, pp. 215–237, 2008

- ↑ Pettinato, Giovanni, "Eridu Texts", Time and History in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 56th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Barcelona, July 26th-30th, 2010, edited by Lluis Feliu, J. Llop, A. Millet Albà and Joaquin Sanmartín, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 799-802, 2013

- ↑ G. Marchesi, "The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia", in:ana turri gimilli, studi dedicati alPadre Werner R. Mayer, S.J. da amici e allievi, Vicino Oriente Quader-no5, Rome: Università di Roma, pp. 231–248, 2010

- ↑ "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature".

- ↑ "The Sumerian king list: translation". etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ↑ Rogers, John H. (1998). "Origins of the Ancient Constellations: I. The Mesopotamian Traditions". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 108 (1): 9–28. Bibcode:1998JBAA..108....9R.

- ↑ Bautsch, Markus; Pedde, Friedhelm. "Canopus, der "Stern der Stadt Eridu"" (PDF). Dem Himmel Nahe (in German) (17): 8–9. ISSN 2940-9330.

- ↑ UET 6, 61 + UET 6, 503 + UET 6, 691 (+) UET 6, 701 or CDLI Literary 000357, ex. 003 (P346146)

- ↑ Peterson, Jeremiah (January 2018). "The Divine Appointment of the First Antediluvian King: Newly Recovered Content from the Ur Version of the Sumerian Flood Story". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 70 (1): 37–51. doi:10.5615/jcunestud.70.2018.0037.

- ↑ Cavigneaux, Antoine. “Une version Sumérienne de la légende d’Adapa (Textes de Tell Haddad X) : Zeitschrift Für Assyriologie104 (2014): 1–41.

- ↑ Peterson 2018, p. 40.

- ↑ Brandon, S. G. F., "The Origin of Death in Some Ancient Near Eastern Religions", Religious Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 217–28, 1966

- ↑ Milstein, Sara J., "The “Magic” of Adapa", Texts and Contexts: The Circulation and Transmission of Cuneiform Texts in Social Space, edited by Paul Delnero and Jacob Lauinger, Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 191-213, 2015

- ↑ Jacobsen, Thorkild, "The Eridu Genesis", Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 100, no. 4, pp. 513–29, 1981

- ↑ Gertrud Farber-Fliigge, "Der Mythos 'Inanna und Enki' unter besonderer Berücksichti-gung der Liste der me", Rome, St Pohl 10, 1973

- ↑ Alster, Bendt, "On the Interpretation of the Sumerian Myth 'Inanna and Enki'", vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 20-34, 1974

- ↑ Green, M. W., "The Eridu Lament.", JCS 30, pp. 127–67, 1978

- ↑ Ilan Peled, "A New Manuscript of the Lament for Eridu", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 67, pp. 39–43, 2015 doi:10.5615/jcunestud.67.2015.0039

- ↑ The lament for Eridug ETSCL

- ↑ Green, Margaret Whitney, "Eridu in Sumerian Literature", Unpublished Ph.D Dissertation, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, 1975

- ↑ P. Delougaz, A Short Investigation of the Temple at Al-'Ubaid, Iraq, vol. 5, pp. 1-11, 1938

- ↑ AR George, "House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia", Eisenbrauns, 2003 ISBN 0-931464-80-3

- ↑ Fabrizio Serra ed., "A new foundation clay-nail of Nūr-Adad from Eridu", Oriens antiquus : rivista di studi sul Vicino Oriente Antico e il Mediterraneo orientale : I, pp. 191-196, 2019

Further reading

- Seton Lloyd, "Ur-al 'Ubaid, 'Uqair and Eridu. An Interpretation of Some Evidence from the Flood-Pit", Iraq, British Institute for the Study of Iraq, vol. 22, Ur in Retrospect. In Memory of Sir C. Leonard Woolley, pp. 23–31, (Spring - Autumn, 1960)

- Lloyd, S., "The Oldest City of Sumeria: Establishing the origins of Eridu.", Illustrated London News Sept. 11, pp. 303-5, 1948.

- Joan Oates, "Ur and Eridu: the Prehistory", Iraq, vol. 22, pp. 32-50, 1960

- Joan Oates, "Ur in Retrospect: In Memory of Sir C. Leonard Woolley", pp. 32-50, 1960

- Mahan, Muhammed Seiab. "Topography of Eridu and its defensive fortifications", ISIN Journal 3, pp. 75-94, 2022

- Margueron, Jean, "Notes d’archéologie et d’architecture Orientales: 3: Du Nouveau Concernant Le Palais d’Eridu?", Syria, vol. 60, no. 3/4, pp. 225–31, 1983

- Quenet, Philippe, and Anne-Caroline Rendu Loisel, "La campagne du printemps 2022 à Eridu, Irak du Sud", Les Chroniques d'ARCHIMEDE 3, pp. 5-8, 2022

- Reisman, Daniel, "Ninurta’s Journey to Eridu", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 24, no. 1/2, pp. 3–10, 1971

- Van Buren, E. Douglas, "Discoveries at Eridu", Orientalia, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 123–24, 1949

- Yassin, Ali Majeed, "Gully erosion model of the archaeological site of Eridu Ziggurat in the southern plateau of Iraq using RS-GIS technology", Thi Qar Arts Journal 3.41, pp. 1-20, 2023 (in arabic)

- "The Ruins of Eridu, 2400 B. C.", Scientific American, vol. 83, no. 20, pp. 308–308, 1900

External links

- The Sumerian king list: translation, UK: Oxford

- Archaeological Photographs from Eridu, IL, USA: Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

- Eridu object held at the British Museum

- Inana and Enki, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford UK, JAB, editor: translation

- Iraq launches campaign to secure archaeological sites in Dhi Qar Al-Mashareq 2021-09-24