| The Last of the Mohicans | |

|---|---|

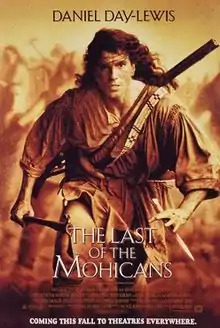

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Mann |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dante Spinotti |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 112 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | |

| Budget | $40 million[4] |

| Box office | $143 million |

The Last of the Mohicans is a 1992 American epic historical action drama film directed by Michael Mann, who co-wrote the screenplay with Christopher Crowe, based on the 1826 novel of the same name by James Fenimore Cooper and its 1936 film adaptation. The film is set in 1757 during the French and Indian War. It stars Daniel Day-Lewis, Madeleine Stowe, and Jodhi May.

The soundtrack features music by Trevor Jones and Randy Edelman, and the song "I Will Find You" by Clannad. The main theme of the film is taken from the tune "The Gael" by Scottish singer-songwriter Dougie MacLean.

The Last of the Mohicans was released in the United States on September 25, 1992. The film received generally positive reviews from critics and was a commercial success. It won the Academy Award for Best Sound, the only Academy Award won so far by a film directed by Mann.[5]

Plot

In 1757, British Army Major Duncan Heyward arrives in Albany, New York, during the French and Indian War. He is assigned to Colonel Edmund Munro, the commander of Fort William Henry in the Adirondack Mountains. Heyward is tasked with escorting Munro's two daughters, Cora and Alice, to their father. Before they leave, Heyward asks Cora to marry him, but she asks for more time before giving her answer.

A Mohawk named Magua is tasked with guiding Heyward, the two women, and a troop of British soldiers to the fort, but he is actually a Huron who leads them into an ambush that kills most of the soldiers. Mohican Chingachgook, his son, Uncas and his white adopted son, "Hawkeye", arrive and kill all of the Hurons except Magua, who escapes. The trio agrees to take the women and Heyward to the fort. During the trek, they find another massacre at a farm, but do not stop to bury the victims so as not to alert the Hurons to their presence. Cora and Hawkeye are attracted to each other, as are Uncas and Alice.

They find the fort under siege by the French and their Huron allies, but manage to sneak in. Colonel Munro is surprised to see his daughters, as he had sent a letter warning them to stay away, but it never reached them. Heyward becomes jealous of Hawkeye when Cora tells Heyward she will not accept his marriage proposal. A militiaman sets out at night to try to reach general Webb at Fort Edward for reinforcements, with Hawkeye, Chingachgook and Uncas providing covering fire from the fort.

After Munro refuses to honor an agreement made by Webb that the militiamen could leave to protect their homesteads if they were threatened, Hawkeye helps them sneak away. He is arrested for sedition and sentenced to hang. But when he learns that Webb will send no soldiers, Munro is forced to accept French general Louis-Joseph de Montcalm's terms of surrender; the British can leave the fort honorably with their arms. Magua is furious because he bears a personal grudge against Munro.

Once Munro, his soldiers and civilians leave the fort, Huron warriors attack and massacre them. Munro is captured alive, but mortally wounded, and Magua personally promises him that he'll kill his daughters, then cuts out his heart. Hawkeye, Uncas, and Chingachgook fight their way out, taking Cora, Alice, Heyward, and a few British soldiers. They hide in a cave behind a waterfall, but Magua finds them. Before Hawkeye, Uncas, and Chingachgook escape by leaping from the waterfall, Hawkeye tells Cora to stay alive and swears that he will find her.

Magua takes his three prisoners to a Huron settlement. While he is addressing a sachem, Hawkeye walks in unarmed as a parley to plead for their lives. The sachem rules that Heyward is to be returned to the British, Alice be given to Magua for the wrongs done to him by Munro, and Cora be burned alive. Although Hawkeye is told he may leave in peace for his bravery, he offers to take Cora's place. Heyward, who is acting as interpreter, instead tells the Hurons to take his life for Cora's. After Hawkeye leaves the village with Cora he shoots Heyward, who is being burned alive, as a final act of mercy.

Chingachgook, Uncas and Hawkeye then pursue Magua's party to rescue Alice. Uncas races ahead and kills several of the Hurons in combat, but is killed in a duel by Magua and thrown off the cliff's edge. Devastated to see Uncas' demise, Alice refuses to remain with Magua and commits suicide by jumping off the same cliff. Enraged, Hawkeye and Chingachgook catch up to the Hurons and slay many of them. Hawkeye then holds the rest at gunpoint, allowing Chingachgook to fight and kill Magua, avenging Uncas' death. Afterward, Chingachgook prays to the Great Spirit to receive Uncas, proclaiming himself "the last of the Mohicans".

Cast

- Daniel Day-Lewis as Nathaniel "Hawkeye" Poe

- Madeleine Stowe as Cora Munro

- Russell Means as Chingachgook

- Eric Schweig as Uncas

- Jodhi May as Alice Munro

- Steven Waddington as Major Duncan Heyward

- Wes Studi as Magua

- Maurice Roëves as Colonel Edmund Munro

- Patrice Chéreau as General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm

- Edward Blatchford as Jack Winthrop

- Terry Kinney as John Cameron

- Tracey Ellis as Alexandra Cameron

- Dennis Banks as Ongewasgone

- Pete Postlethwaite as Captain Beams

- Colm Meaney as Major Ambrose

- Mac Andrews as General Webb

- Malcolm Storry as Phelps

- David Schofield as Sergeant Major

- Eric D. Sandgren as Coureur de Bois

- Mark Edrys as Captain Bougainville

- Tim Hopper as Ian

- Jared Harris as British Lieutenant

- Sebastian Roché as Martin

Production

Development

Much care was taken with recreating accurate costumes and props. Daniel Winkler made the tomahawks used in the film and knifemaker Randall King made the knives.[6] Wayne Watson is the maker of Hawkeye's "Killdeer" rifle used in the film. The gunstock war club made for Chingachgook was created by Jim Yellow Eagle. Magua's tomahawk was made by Fred A. Mitchell of Odin Forge & Fabrication.

Costumes were originally designed by multiple Academy Award winner James Acheson, but he left the film and had his name removed because of artistic differences with Mann. Designer Elsa Zamparelli was brought in to finish.

Casting

Through the making of this film, actors Wes Studi and Maurice Roëves became lifelong friends.[7]

Locations

Although the story takes place in upstate colonial New York, filming was done mostly in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina.[8] Locations used include Lake James, Chimney Rock Park and The Biltmore Estate. Some of the waterfalls that were used in the movie include Hooker Falls, Triple Falls, Dry Falls (near Highlands, NC), Bridal Veil Falls, and High Falls, all located in the DuPont State Recreational Forest.[8] Another of these falls was Linville Falls, in the mountains of North Carolina. Also, Hickory Nut Falls at Chimney Rock was in the movie near the end. Scenes of Albany were shot in Asheville, North Carolina at The Manor on Charlotte Street.[8]

The set of Fort William Henry was constructed at a reported cost of US$6 million on felled forestry land (35°47′40.69″N 81°52′12.10″W / 35.7946361°N 81.8700278°W) adjacent to Lake James in North Carolina. Highway 126, which ran between the set and the lake, had to be closed for the duration of the filming.[9]

Soundtrack

Release

The film opened in the United States on September 25, 1992, in 1,856 theaters. It was the number one movie on its opening weekend.[10][11] By the end of its first weekend, The Last of the Mohicans had generated $10,976,661, and by the end of its domestic run, the film had made $75,505,856 in the United States and Canada.[4] It was ranked the 17th highest-grossing film of 1992 in the United States.[12] Internationally, the film grossed more than $67 million[13] for a worldwide total of over $143 million.

Alternate versions

When the film was released theatrically in the United States, its running time was 112 minutes. This version of the film was released on VHS in the U.S. on June 23, 1993. The film was later re-edited to a length of 117 minutes,[14] for its U.S. DVD release on November 23, 1999,[15] which was billed as the "Director's Expanded Edition". The film was again re-edited for its U.S. Blu-ray release on October 5, 2010,[16] this time billed as the "Director's Definitive Cut", with a length of 114 mins.[17] At Mann's insistence, all home video releases of the film, including in its original VHS releases, have been presented in the original theatrical aspect ratio.

Reception

On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a rating of 88% based on reviews from 127 critics, with an average rating of 7.7/10. The site's consensus states: "The Last of the Mohicans is a breathless romantic adventure that plays loose with James Fenimore Cooper's novel – and comes out with a richer action movie for it."[18] On Metacritic, the film holds a weighted average score of 76 out of 100 based on 18 critics.[19] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A-" on an A+ to F scale.[20]

The Last of the Mohicans opened with critics praising the film for its cinematography and music. Critic Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three stars and called it "quite an improvement on Cooper's all but unreadable book, and a worthy successor to the Randolph Scott version", going on to say that "The Last of the Mohicans is not as authentic and uncompromised as it claims to be – more of a matinee fantasy than it wants to admit – but it is probably more entertaining as a result."[21]

Desson Howe of The Washington Post classified the film as "glam-opera" and "the MTV version of gothic romance".[22] Rita Kempley of the Post recognized the "heavy drama", writing that the film "sets new standards when it comes to pent-up passion", but commented positively on the "spectacular scenery".[23]

The film has also been criticized for having continued to perpetuate Native American stereotypes (for example, the "noble" vs "bloodthirsty" savage, embodied in, respectively, Uncas and Magua), centering a white savior narrative, and furthering the settler-colonial myth of Indigenous peoples as a single "vanishing race".[24]

Awards and nominations

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20/20 Awards | Best Original Score | Trevor Jones and Randy Edelman | Nominated |

| Academy Awards[25] | Best Sound | Chris Jenkins, Doug Hemphill, Mark Smith and Simon Kaye | Won |

| American Cinema Editors Awards | Best Edited Feature Film | Dov Hoenig and Arthur Schmidt | Nominated |

| American Society of Cinematographers Awards | Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography in Theatrical Releases | Dante Spinotti | Nominated |

| Awards Circuit Community Awards | Best Cinematography | Nominated | |

| Best Makeup & Hairstyling | Peter Robb-King and Vincent J. Guastini | Nominated | |

| Best Sound | Chris Jenkins, Doug Hemphill, Mark Smith, Simon Kaye, Lon Bender and Larry Kemp | Nominated | |

| BMI Film & TV Awards | Film Music Award | Randy Edelman | Won |

| British Academy Film Awards[26] | Best Actor in a Leading Role | Daniel Day-Lewis | Nominated |

| Best Cinematography | Dante Spinotti | Won | |

| Best Costume Design | Elsa Zamparelli | Nominated | |

| Best Make Up Artist | Peter Robb-King | Won | |

| Best Original Film Score | Trevor Jones and Randy Edelman | Nominated | |

| Best Production Design | Wolf Kroeger | Nominated | |

| Best Sound | Simon Kaye, Lon Bender, Larry Kemp, Paul Massey, Doug Hemphill, Mark Smith and Chris Jenkins | Nominated | |

| British Society of Cinematographers[27] | Best Cinematography in a Theatrical Feature Film | Dante Spinotti | Nominated |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards[28] | Most Promising Actor | Wes Studi | Nominated |

| Evening Standard British Film Awards | Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won |

| Golden Globe Awards[29] | Best Original Score | Trevor Jones and Randy Edelman | Nominated |

| London Film Critics Circle Awards | British Actor of the Year | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won |

| Nastro d'Argento | Best Cinematography | Dante Spinotti | Nominated |

| Political Film Society Awards | Peace | Nominated | |

| Southeastern Film Critics Association Awards[30] | Best Picture | 9th Place | |

American Film Institute recognition:

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Hawkeye - Nominated Hero[31]

References

- ↑ "The Last of the Mohicans (1992)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

A 26 Sep 1991 DV article announced distribution rights to foreign territories outside the U. S. and Canada were sold for $17 million to Morgan Creek International (MCI), in a deal that marked MCI's "first acquisition of a third-party film."

- ↑ "The Last of the Mohicans". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Languages in Last of the Mohicans". Native-Languages.org. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- 1 2 "The Last of the Mohicans (1992)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 2, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ↑ Weinrub, Bernald (March 30, 1993). "Oscar's night started at noon in Hollywood". The New York Times. p. 9. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Haskew, Mike (September 1, 2006). "Star-Spangled Hawks Take Wing". Vol. 33, no. 9. Blade Magazine. pp. 30–37.

- ↑ "Scots actor Maurice Roeves dies aged 83". BBC News. July 15, 2020. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- 1 2 3 "The Last of the Mohicans". www.movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ↑ "THE FILMING AT LAKE JAMES". www.mohicanpress.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2019. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Weekend Box Office". The Los Angeles Times. October 6, 1992. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ↑ Fox, David J. (October 6, 1992). "Box Office Hasn't Seen the Last of 'Mohicans". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ↑ "1992 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ↑ Groves, Don (April 19, 1993). "Disney fare is cats' meow; Clint rides". Variety. p. 34.

- ↑ Wurm, Gerald (April 7, 2010). "Last of the Mohicans, The (Comparison: Theatrical Version - Director's Expanded Edition)". Movie-Censorship.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Last of the Mohicans (Director's Expanded Edition): Daniel Day-Lewis, Madeleine Stowe, Russell Means, Eric Schweig, Jodhi May, Steven Waddington, Wes Studi, Maurice Roëves, Patrice Chéreau, Edward Blatchford, Terry Kinney, Tracey Ellis, Michael Mann, Christopher Crowe, Daniel Moore, James Fenimore Cooper, John L. Balderston, Paul Perez, Philip Dunne: Movies & TV". Amazon. November 23, 1999. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "The Last of the Mohicans Blu-ray: Director's Definitive Cut". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ Wurm, Gerald (October 29, 2010). "Last of the Mohicans, The (Comparison: Theatrical Version - Director's Definitive Cut)". Movie-Censorship.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ "The Last of the Mohicans". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on March 22, 2007. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ↑ "The Last of the Mohicans Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ↑ "Home". Cinemascore. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (September 25, 1992). "The Last of The Mohicans". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 28, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ↑ Howe, Desson (September 25, 1992). "The Last of The Mohicans". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ↑ Kempley, Rita (September 25, 1992). "The Last of The Mohicans". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 8, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2007.

- ↑ Rinne, Craig, White Romance and American Indian Action in Hollywood's The Last of the Mohicans (1992), Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 13, no. 1, 2001, pp. 3–22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20736998

- ↑ "The 65th Academy Awards (1993) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ↑ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1993". BAFTA. 1993. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Best Cinematography in Feature Film" (PDF). Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ↑ "1988-2013 Award Winner Archives". Chicago Film Critics Association. January 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ↑ "The Last of the Mohicans – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "1992 SEFA Awards". sefca.net. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains Nominees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

External links

- Kristopher Tapley: Michael Mann looks back on 'The Last of the Mohicans' 20 years later at uproxx.com

- The Last of the Mohicans at IMDb

- The Last of the Mohicans at the TCM Movie Database

- The Last of the Mohicans at AllMovie

- The Last of the Mohicans at Box Office Mojo

- The Last of the Mohicans at the American Film Institute Catalog