| Lavushi Manda National Park | |

|---|---|

| |

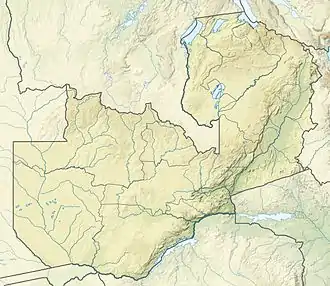

| Location | Zambia |

| Coordinates | 12°19′S 30°51′E / 12.317°S 30.850°E |

| Area | 1,500 km² |

| Established | 1972 |

| Governing body | Department of National Parks and Wildlife |

Lavushi Manda National Park is a national park in the Muchinga Province of Zambia with an area of 1,500 sq km.[1] It is the 11th largest of the 20 National Parks in Zambia.[2] The park was initially gazetted as a Game Reserve in 1941, and was declared a National Park in 1972.[2] It is located in Muchinga Province,[3] in a district of the same name (Lavushimanda), with the South Luangwa National Park in the neighbouring Mpika District.[2] It is adjacent to Bangweulu Game Management Area to the northwest, Kafinda Game Management Area lies further west. The chiefdom of Chiundaponde (Bisa people) is in the northwest, north lies Luchembe, northwest Chikwanda, east Mpumba (Bisa people), and south lies Muchinka chiefdom.[4] It covers a small range of mountains and hills, and is principally covered in miombo woodlands, with a number of rivers and streams, and a few areas of grassland, both on drier land or in the form of seasonally wet dambos. There are few large mammals, due to poaching in the previous century, but fishing and hiking are possible. Certain antelope species retreat upland to the park from the Bangweulu swamps to the northwest during the rainy season.

Geology and hydrology

Lavushi Manda lies on the plateau area of Lavushimanda District between the Muchinga Escarpment and the alluvial flats of the Bangweulu floodplain.[2] The scenery is dominated by the 40[1] to 47 km long Lavushi mountains in the southern half of the park. This range reaches up to 1,811 meters altitude, forming one of the highest points in Zambia.[2] The rocks in the rugged landscape are mainly quartzites, which are ancient metamorphosed sandstones.[5]

Away from this range, the park is dominated by undulating or rather flat terrain, covered by vast stretches of miombo woodlands interspersed with large seasonally wet grasslands and valleys (dambos) feeding into numerous seasonal and perennial streams. Evergreen riparian forest lines much of the banks of the perennial streams.[1]

There are numerous seasonal and perennial streams. Perennial rivers which drain the park are, from southwest to northeast, the Lulimala, Lukulu,[1][6] Lumbatwa[6] (including the Lubweshi) and Mufubushi. All of these streams form part of the boundaries and, with the exception of the Lukulu, have their sources on the boundaries of the park.[3] These streams all flow into Lake Bangweulu.[1] Kapanda Lupili and Mumba Tuta are two waterfalls on the Lukulu as it enters and exits the park, respectively;[6][7] the Kanyanga waterfalls are also in the park on this river.[8][9] The Lukulu is normally a small river, but in December heavy rains begin which colour and raise the level of the water, and increase flows.[10]

There are numerous rocky pans and flat plains throughout the park which form seasonal lakes. Although there are no truly permanent lakes in the park, the Chibembe plain and Lake Mikonko keep a substantial surface of standing water well into the dry season.

Habitats

The habitats within the park are the Lavushi mountains, large dambo grasslands, woodlands, streams and rivers.[1]

Deciduous, open forest covers approximately 80% of the park. Miombo woodland is the principal type, especially in the hills,[1] characterised by a dominance of trees from the genera Brachystegia, Isoberlinia, Julbernardia and Uapaca.

Riparian forest occurs as a narrow evergreen strip following the perennial streams[1] or as a deciduous or semi-deciduous strip fringing the seasonal streams.

The grasslands in the park are especially seasonally wet headwater dambo grasslands.[1] Bog grasslands are common especially near the mountains where seepage water creates year-round wet conditions.

Flora

Hibiscus meeusei has been collected at higher altitudes just within the park.[11] Agarista salicifolia was collected on Lavushi Mountain,[12] and Justicia richardsiae was found growing on hard laterite pan soil.[13] A typical feature of the riparian forests in Lavushi Manda are the frequent presence of Raphia farinifera (raphia palm), which is absent in the nearby Kasanka National Park.

Fauna

Mammals

Protracted poaching has led to a serious depletion of all larger mammal populations. The last wild black rhinoceros in Zambia was observed in LMNP in the late eighties.[1] Warthog[14] and common duiker are sometimes sighted. Primates include vervets[6][14] and yellow baboons, sometimes classified as Kinda baboons.[14] In the grasslands there are side-striped jackal,[6][14] sable antelope and bushbuck.[14] In the wet season antelopes such as the roan, sable and hartebeest move upland to the area from the swamps of Bangweulu.[1] Lions may occur in the park, but have never been sighted.[14] A camera trap survey in 2017 found several herds of sable, and several bush pig, common duiker, reedbuck, bushbuck, aardvark, African civet and serval. One leopard was caught on camera in Lavushi Manda in 2017.[4]

In 2017 150 puku were moved from Kasanka National Park to the Bangweulu Game Management Area by African Parks, a number quickly moved from there into the Chimbwe plain and lower Lukulu river valley in LMNP.[4]

Klipspringer, bush dassie and Smith's red rock rabbits occur among the rocks.[6][14] There are hippopotami in the Lukulu river.[14]

Birds

_-_in_Lavushi_Manda_National_Park%252C_Zambia_by_Christiaan_van_der_Hoeven.jpg.webp)

A checklist was complied by the Kasanka Trust in 2011 of potential bird species which the park might hold.[15] In 1998 BirdWatch Zambia went birdwatching in the park for BirdLife International. A number of exclusively miombo birds were registered in 1998, and the list of these birds were used by BirdLife International to designate Lavushi Manda as an "Important Bird Area" as of 2001, for protecting common species typical of the vast miombo regions of Southern Africa. The only bird thought to possibly occur in the park at the time which was considered somewhat rare (at the time) was the migratory great snipe, which might arrive in the winter. The designation included the nearby Luitikila Forest Reserve and Bangweulu Game Management Area, although the national park appears to be the only locality studied in 1998.[16]

Lavushi Manda is home to rock-associated species such as black eagles, Augur buzzards,[6][16] freckled nightjar, striped pipit, mocking chat and red-winged starling. Dambo grasslands support marsh widowbird and locustfinch. Stanley's bustard, a typical dry grassland species, has been recorded.[16] The coqui francolin was photographed in the park in 2017.[17] Miombo woodlands hold a variety of typical birds of this habitat such as pale-billed hornbill, racquet-tailed roller, Souza's shrike, Böhm's flycatcher, Böhm's bee-eater, Anchieta's barbet, miombo pied barbet, white-faced barbet, Anchieta's sunbird, western miombo sunbird, Hartlaub's babbler,[16] Kurrichane thrush,[16][18] miombo scrub-robin, miombo rock-thrush, Stierling's wren-warbler,[16] red-capped crombec, miombo tit, rufous-bellied tit, black-necked eremomela,[16][18] brown firefinch, Fülleborn's longclaw, black-eared seedeater, Tabora cisticola,[16] Arnot's chat[16][18] and bushveld pipit. All but the last were spotted here in the 1998 BirdWatch Zambia excursion.[16] A July 2018 visit under the eBird program also observed the following additional species in the park: cardinal woodpecker, emerald-spotted wood dove, ring-necked dove, black-backed puffback, white-breasted cuckooshrike, southern black flycatcher, fork-tailed drongo, red-headed weaver, black-crowned tchagra, tawny-flanked prinia, golden-breasted bunting, green-capped eremomela, chinspot batis, yellow-bellied hyliota and swallow-tailed bee-eater.[18]

African finfoot, African broadbill, Ross' turaco,[3][10][14] Schalow's turaco,[3] narina trogon[3][10] and chestnut-bellied kingfisher occur in the park near the rivers.[14] The palm-nut vulture is a common sight in the thick riverine gallery forests while in a kayak.[3][7][10][14] The sunbird Nectarinia chalybea pintoi was collected in the park in 1954, when it was still a game reserve,[19] as was Apalis thoracica ssp. whitei.[20] The apalis, Böhm's flycatcher, black sparrowhawk and Pel's fishing owl are also found in riparian forests.[16]

The park hosts large numbers of several Palaearctic and African migrants.[1] Collared flycatchers are a common wintering visitor in the miombo.[16]

Reptiles and amphibians

A checklist was complied in 2015 of potential species which the park might hold.[21]

There are Nile crocodiles which occur in the Lukulu river.[14] A sand snake identified at the time as Psammophis sibilans was collected in this region in 1932 ("Nsanga River" west of Lavushi), before it had even become a game reserve,[22] although recent studies of this species would likely classify it as either Ps. orientalis, Ps. mossambicus or the recently described Ps. zambiensis.[23] Similarly, Gerrhosaurus nigrolineatus was identified in the "Lavushi Hills" some time before 1934,[24] but a more recent taxonomy would possibly classify this record as G. intermedius, although it is essentially unclear.[25]

A herping excursion in December 2015 found the skink Mochlus sundevalli (at Fibishi Camp) and the chameleon Chamaeleo dilepis in the park.[26] Possibly unique new forms of the skinks Trachylepis varia (on the mountain range) and T. striata were found in the park.[26][27] Frogs found were Ptychadena grandisonae and Tomopterna tuberculosa.[26]

Fish

Biodiversity in catches downstream from Mumba Tuta Falls is higher than further upstream, suggesting that these falls are a barrier for fish migration.

The top sportfish caught in the rivers here is a large, green fish locally known as mpifu (or ntifu?), this is a type of yellowfish only found regionally.[3][7] In 2011 this was first identified as a species similar to Labeobarbus trachypterus,[8] it may be L. stappersi.[10] It is found in forested, rocky areas in the fast-flowing main channel and rapids of the Lukulu river.[8] Other sportfish are breams such as a large nembwe-like Serranochromis (locally known as nsuku?) and redbreast kurper (Tilapia rendalli), which are found in the same river habitat as the above yellowfish, and thinface largemouth (Serranochromis angusticeps) which is found in woodland streams.[3][8][10] Other breams found in these streams are S. thumbergi, vlei kurper or banded bream (Tilapia sparrmanii),[8] and three spot bream (Oreochromis andersonii).[3]

The barb Enteromius paludinosus[9] and Micralestes sardina were caught in the park in the Lukulu River, in the last case in fast-flowing waters with a rocky bottom and forested sides. African carp (Labeo cylindricus), dwarf bream (Pseudocrenilabrus philander), a 4-5cm Varicorhinus and the barbs Enteromius brevidorsalis and E. bifrenatus are found on rocky riffles and runs in the main river channel. A barb similar to E. paludinosus, the threespot barb (Barbus trimaculatus), and a 5cm Cyphomyrus were found in woodland streams in a habitat with rocky rapids and pools with trees and logs. Brycinus peringueyi was found in both woodland streams as well as the main river, but not in rocky riffles and runs. The barb Enteromius eutaenia (known locally as jimbo?) and the catfish Clarias stappersii were found at all sites.[8]

_collected_in_Zambia_by_South_African_Institute_for_Aquatic_Biodiversity.jpg.webp)

Insects

The dung-rolling scarab beetle Garreta dejeani was collected on some carrion in the Manda Hills in the park.[28]

The flea beetles Medythia exclamationis and Physonychis violaceipennis; the marsh beetle Contacyphon des; the leaf beetles Neobarombiella senegalensis and Monolepta vincta; the longhorn beetles Ceroplesis militaris, Chromalizus leucorrhaphis and Macrotoma palmata; and the chafer beetles Eulepida zambiensis and Pachnoda allardi were collected along the Lukulu river. The Physonychis, Neobarombiella, Macrotoma and Eulepida were collected more than once, the marsh beetle and an unidentified species of Cicindelina were especially common. A large number of other unidentified insects were also captured.[28]

Management

Prior to 2011 resources available to be committed to Lavushi Manda National Park had dwindled such that there was no effective management. Poaching within the park had been rife, with all large mammal numbers being almost completely wiped out. The Kasanka Trust, which has been entrusted with operating the nearby Kasanka National Park,[1][29] extended its operations to Lavushi Manda with funding provided by the World Bank to build park infrastructure such as administrative buildings, a road network and a basic conservation centre.[29] The appointed park manager was Frederick Mbulwe, who retired in 2017. Poaching increased sharply in 2014 and continued to be a problem, this is believed to be due to the new management of Bangweulu Game Management Area by African Parks, a South African park management NGO. They were very successful at combating poaching, which is thought to have displaced bushmeat traders south.[4] By 2016 all illegal settlers within the park had been evicted. Comprehensive large mammal counts were abandoned in the mid-2010s, but by 2017 a significant decline in the abundance of most antelope species since 2014 was apparent. On the other hand, sighting data from patrol reports between 2012 and 2016 showed a slight increase in sightings of most species. Sable antelope and warthog were chosen in 2017 as indicator species for future management target counts in the park, although no counts occurred.[4]

Fire management is conducted in the early dry season by setting off wildfires, primarily to thwart poachers which may potentially set late and more destructive fires in September–November. Unplanned fires have been minimal during the 2010s.[4]

Law enforcement is provided by Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) rangers and wildlife police officers. There were 24 arrests in 2016. Surrounding chiefdoms have Community Resources Boards (CRB) organised with the DNPW. Additional law enforcement was funded by the World Land Trust, 25 village scouts were employed in 2017 from the Mpumba CRB to patrol the zone near the chiefdom, including the Luwombwa sector in the park and adjoining parts of Kafinda Game Management Area. They made 34 arrests and there were 22 convictions for poaching. Especially bushpig and common duiker were targeted with firearms or wire snares. Mpumba hunters voluntary surrendered twenty guns in 2016. Chiundaponde CRB also sometimes patrols areas adjoining that chiefdom.[4]

There were 32 bed-nights (not the same as visitors) to the park in 2016, or a 3% occupancy rate. Ecotourists spent $330 that year.[4]

The Kasanka Trust managed the park for DNPW, under a memorandum of understanding, in exchange for developing the road network in the park while working with DNPW on combating poaching.[1][29] The not-for-profit trust generated funds to operate Lavushi Manda mainly from external funding in the form of grants and donations, but also for a degree on its tourism operations at Kasanka National Park. Approximately a third of its funds went to Lavushi Manda. In 2017 Kasanka Trust relinquished management of the park back to DNPW, citing financial and managerial issues. Some of the road network in the park had been maintained, other roads had been neglected. The boundaries of the park are demarcated by cut lines, but these are not always maintained.[4]

Tourism

Park entrance fees were approximately USD $5 for international visitors in 2018, while camping fees were USD $15 per person per night. Vehicle fees were USD $1.70 for local vehicles and USD $15 for internationally-licensed vehicles.[6] Park fees and camping fees must be paid at the entrance to the park.[3][6][10] There are three basic campsites: Mumba Tuta, Kapanda Lupilli and Peak. There are two sites with more permanent Meru-style tents at Mumba Tuta and Linda Camp, the headquarters.[3] There was once a campsite on the Chibembe, but it is no longer maintained.

It is possible to hike unaccompanied in the park.[3][6] It is a two-and-a-half hour hike to the summit of Lavushi Mountain.[6] Recreational angling is only possible in the park with a valid DNPW permit from April/May to December. No bait fishing and barbed hooks are allowed, and catch and release is the rule. There are kayaks available. The river is heavily vegetated and so bank fishing is near impossible from all but a few places. Hippos and crocodiles are dangers.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Zambia Tourism - Lavushi Manda National Park". Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Lavushimanda". Provincial Administration, Muchinga Province. SMART Zambia Institute. 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Fishing the hidden rivers of Lavushi". Lavushi Manda National Park. Kasanka Trust. 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kasanka Trust Annual Report 2017 (PDF) (Report). Kasanka Trust Ltd. 2017. p. 1-48. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ↑ Mischler, John (29 June 2012). "Lavushi Manda National Park". Conservation Ecology in Zambia. Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kapambwe, Mazuba (5 April 2018). "The Most Beautiful Hiking Trails in Northern Zambia". The Culture Trip. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 "The Hidden Gems within Lavushi Manda National Park". Hidden Gems of Zambia. 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Coetzer W (2020). Occurrence records of southern African aquatic biodiversity. Version 1.33. The South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/pv7vds accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/search?q=Lavushi%20Manda&country=ZM&dataset_key=1aaec653-c71c-4695-9b6e-0e26214dd817

- 1 2 European Nucleotide Archive (EMBL-EBI) (2019). Geographically tagged INSDC sequences. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/cndomv accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/2310628546

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Fishing Lavushi Manda–The Quest for the 'Congo' Yellowfish..." (PDF). Lavushi Manda National Park. 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ↑ Gaisberger H, Endresen D (2019). Bioversity Collecting Mission Database. Version 1.10. Bioversity International. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/ulk1iz accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/1563482491

- ↑ Bijmoer R, Scherrenberg M, Creuwels J (2021). Naturalis Biodiversity Center (NL) - Botany. Naturalis Biodiversity Center. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/ib5ypt accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/2517480778

- ↑ Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (2021). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew - Herbarium Specimens. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/ly60bx accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/912450905

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Wildlife in Lavushi Manda". Lavushi Manda National Park. Kasanka Trust. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ↑ Willems, Frank (April 2011). "Birdlist Lavushi Manda National Park" (PDF). Lavushi Manda National Park. Kasanka Trust. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Important Bird Areas factsheet: Lavushi Manda National Park". BirdLife International. 2001. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ Christiaan van der Hoeven, Stichting Natuurinformatie in de Vries H, Lemmens M. Observation.org, Nature data from around the World. Observation.org. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/5nilie accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/2843372398

- 1 2 3 4 Levatich T, Ligocki S (2020). EOD - eBird Observation Dataset. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/aomfnb accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/search?q=Lavushi%20Manda&country=ZM&dataset_key=4fa7b334-ce0d-4e88-aaae-2e0c138d049e

- ↑ Feeney R (2019). LACM Vertebrate Collection. Version 18.7. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/77rmwd accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/657118577

- ↑ Natural History Museum (2021). Natural History Museum (London) Collection Specimens. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.5519/0002965 accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/1291394550

- ↑ van Hecke, André (2015). "Zambia Aanstreeplijsten" (PDF). FREANonHERPING (in Dutch). André van Hecke. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ Natural History Museum (2021). Natural History Museum (London) Collection Specimens. Occurrence https://doi.org/10.5519/0002965 accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09.

- ↑ Trape, Jean-François; Crochet, Pierre-André; Broadley, Donald G.; Sourouille, Patricia; Mané, Youssouph; Burger, Marius; Böhme, Wolfgang; Saleh, Mostafa; Karan, Anna; Lanza, Benedetto; Mediannikov, Oleg (2019). "On the Psammophis sibilans group (Serpentes, Lamprophiidae, Psammophiinae) north of 12°S, with the description of a new species from West Africa" (PDF). Bonn Zoological Bulletin. 68 (1): 61–91. doi:10.20363/BZB-2019.68.1.061. ISSN 2190-7307. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ Broadley, Donald George (1966). The Herpetology of South-east Africa (PhD, Department of Zoology, University of Natal). Umtali Museum. p. 210. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ Bates, Michael F.; Tolley, Krystal A.; Edwards, Shelley; Davids, Zoë; da Silva, Jessica M.; Branch, William R. (2013). "A molecular phylogeny of the African plated lizards, genus Gerrhosaurus Wiegmann, 1828 (Squamata: Gerrhosauridae), with the description of two new genera". Zootaxa. 3750 (5): 465–493. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3750.5.3. PMID 25113712. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- 1 2 3 van Hecke, André (2016). "Zambia". FREANonHERPING (in Dutch). André van Hecke. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ↑ "Reptiles and Amphibians". Animal Research Connections Zambia. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- 1 2 Natural History Museum (2021). Natural History Museum (London) Collection Specimens. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.5519/0002965 accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-04-09. https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/search?q=Lavushi%20Manda&country=ZM&dataset_key=7e380070-f762-11e1-a439-00145eb45e9a

- 1 2 3 "The Extension of Kasanka Management System to Lavushi Manda National Park". kasanka.com. Kasanka Trust. Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. Retrieved 27 August 2014.