Le Livre de Seyntz Medicines (The Book of Holy Medicines)[2][3] is a fourteenth-century devotional treatise written by Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster around 1354. It is a work of allegory in which he describes his body as under attack from sin: his heart is the castle, and sin—in all its forms—enters his body via wounds, and against which he begs the assistance of the necessary doctor, Jesus Christ. It exists in two complete copies today, both almost identical in language although with different bindings. One of these copies is almost certainly a surviving copy from Grosmont's family, although their provenance is obscure.

Grosmont was one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in England at the time. A close companion of King Edward III, he was a major figure in the early years of the Hundred Years' War and a renowned soldier. He was also conventionally pious and able to put his wealth to demonstrate his piety, for example in the foundation of St Mary de Castro, Newarke, in Leicester Castle. Le Livre de Seyntz Medicines combines both elements from Grosmont's life, and the work is noted for the breadth of its imagery and imagination, much of which is taken from his own personal experience. The work describes Grosmont—a self-acknowledged sinner—talking directly to Christ, who is portrayed as a physician for the physically sick, and who is accompanied by the Virgin Mary as his nurse. Through metaphor, symbolism and allegory Grosmont describes how his body has been attacked by the seven deadly sins which now permeate him and talks his reader through the necessity for confession and penance to allow Christ to perform his work.

Le Livre was probably written at the urging of his friends and relatives, for a literary audience which would have primarily comprised his fellow nobility, but would also have included senior ecclesiastics, lawyers and the educated mercantile class. Historians consider it to be one of the most important domestic manuscripts extant from the era, not least due to the status and position of its creator. It exists today in a number of manuscript forms and is used by historians not only as a source for the history of books and literacy but also for the broader social and religious conventions of the English nobility.

Le Livre de Seyntz Medicines

Henry of Grosmont's devotional-medical treatise[4][5] is notable for being one of only a few written by individuals of such rank and power in the Middle Ages,[6][note 1] and, to the historian K. B. McFarlane it is "the most remarkable literary achievement of them all" for the period.[10] William Pantin concurred, writing that it was, to him, "one of the most interesting and attractive religious treatises of the period, and especially remarkable as the work of a devout layman".[11] Antonia Gransden has described the piece as "an allegory on the wounds in Henry's soul, discussing the remedies to be supplied by the Divine Physician and his assistant, the Douce Dame", all the while interspersed with personal reminiscences of how he sinned in the first place.[12] Arnould places it within the genre of the Confessions, as well as "the prolific literature of sin".[13] Grosmont sententiously informs the reader how he wishes that when he was young he had "as much covetousness for the kingdom of heaven as I had for £100 of land".[14] He blames those parts of his body which he later accuses of sin: his feet are guilty, for example, of being unwilling to allow him on pilgrimage yet being willing and able to bring him wine.[14] Robert Ackerman has noted that, while Le Livre is an exceptional piece of work in its field, the field is a crowded one, arguing that "moralistic and confessional writings... were produced in overwhelming profusion. Duke Henry could scarcely have found a more time-worn topic and method of treatment when he penned his allegory of the sins and their remedies."[15]

It stands out from both of these categorisations due to its highly personal, almost autobiographical tone,[13] and avoids being merely an exemplum by the images of everyday life—"and finding in everyone a wealth of 'mystic' interpretations"—with which he illustrates the work.[16] Contemporaries understood that to cleanse the soul, one required self-knowledge; this was only obtainable after lengthy, close examination of the self, as Le Livre does.[17] Grosmont states at the beginning that he had numerous motives for writing the work, but the most important was to "make use of times which were wont to be idle in the service of God;"[18] in other words, following the church's dictum that the devil makes work for idle hands.[19] The lengths of paragraphs would appear to reflect the amount of time the author had to work on that section each day, rather than reflect any pre-planning.[18] Structurally, the book is divided into two portions. The first describes the sinner's body, with its wounds of sin, while the second explains the spiritual cures and holy medicines necessary for its healing.[20]

Composition

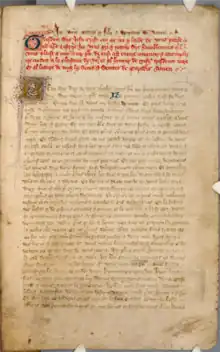

Arnould describes the surviving Stonyhurst copy as being written in a bold, clear hand with each paragraph represented with a large gold initial[21] in a textualis hand.[22] This is accompanied by red and blue ornaments and numerous of his escutcheons and seals.[21] The title, suggests Catherine Batt, maybe a play on that of an earlier text by Matthaeus Platearius, which title in French was Livre des Simples Medicines.[23][note 2] The title is placed just before the explicit.[25] The book is written in the second person, personally directed to Christ in what Pantin calls a "very personal and affectionate way".[26] The prose is not universally popular however; Kaeuper moans that "I fear that some readers who struggle through its turgid prose and allegory gone to seed—244 pages in Anglo-Norman French—may think it penance to read",[27] while Fowler argues that it is "not remarkable"[28] and even Arnould says that in places it is "laborious".[29] It has occasionally been questioned whether Grosmont was the brains behind the work, or whether he had an amanuensis—something he denies in the text[30]—for example, Dominica Legge suggested that this was most likely to have been Grosmont's confessor and that if he could be identified, so would the source of the text's "peculiar quality".[31] Although possibly written by a scribe, Grosmont provides a postscript, including his name written—comments Arnould, "in a naive device prompted by his humbleness"—backwards anagramatically:[21][note 3]

Cest livre estoit comencee et parfaite en l'an de grace Nostre Seignur Jesu Crist MCCCLIIII. Et le fist un fole cheitif peccheour qe l'en appelle ERTSACNAL ED CUD IRNEH, a qi Dieux ses malfaitz pardoynt. Amen.[21]

.jpg.webp)

The book was composed, Teresa Tavormina suggests, "at the urging of friends" of the duke, possibly including[6] the Minoresses of Aldgate, whom he is known to have favoured[34]—or at the instruction of[12]—his confessor, around 1354.[6][note 4] In his opening remarks he says—"shades of a modern author's acknowledgements", comments Labarge—that they should receive equal credit with him for any benefit the book brings.[36] This was a protracted, and probably not easy, exercise for the duke, as whatever his education he had not been brought up in the expectation of ever facing such a task.[37] It is also unlikely that he was in a position to devote any length of time solely to the book's composition; although during this period war with France and Scotland was at a lull, a parliament took place at Westminster between April and May 1354 which he attended. He would also have had much business to attend to connected with his diplomatic mission to Pope Innocent VI in Avignon that October[18] and diplomatic negotiations with Cardinal Guy of Boulogne before then.[36] Tavormina surmises that it was composed in the months either side of Easter, with daily additions.[38] Comprising self-reflective, spiritual assessments, as well as religious contemplations on Christ and the Virgin, Grosmont wrote both for his own genuflection and others' edification.[38] A means of focussing himself on Christ's sacrifice and keeping him from sin, it served as an alternative to traditional forms of devotion, such as prayer.[39]

Grosmont's focus on mortality reflected a renewed interest in the topic which had appeared in the years following the Black Death in 1348 and sporadically since, with a concomitant emphasis on penance regardless of social status.[40] The Bible made it clear to the nobility that, whereas the poor were almost certain to enter heaven, the rich had no such guarantees, and as such the Black Death may have made a more intellectual impact on the aristocracy than the lower classes.[40]

.jpg.webp)

Sins of the author

The book is structured so that the reader receives an overview of Grosmont's self-view before opening himself up to "the Divine assistant and his Assistant", the Douce Dame.[42][note 5] He states that when he was younger, one of his chief sins was that of vanity, stating that "when I was young and strong and agile, I prided myself on my good looks, my figure, my gentle blood and all the qualities and gifts that you, O Lord, had given me for the salvation of my soul". But pride was not confined to himself: he was proud of the richness of his possessions, whether finger rings, shoes, or armour. Likewise his dancing skills or his dress, and much as he flaunted himself he liked, even more, to be praised by others for these things.[46] He also confesses to the sin of sloth, which beset him to such an extent that he regularly failed to rise in time for morning mass, and gluttony, with overindulgence in the best food and drink,[47] with its rich sauces and strong wine.[14] Arnould comments how

Even the sense of smell was a frequent occasion of sin to him, as when he delighted in the sweet scent of the ladies or of anything appertaining to them, or again when he took an inordinate pleasure in smelling the fine scarlet cloth.[48]

And, comments Pantin, "he lets us know that his sensuality did not stop short at smelling scarlet cloth".[26] He was overly fond of music and dancing he says, and indeed he is known to have employed his own troupe of minstrels and had a private dancing chamber built in Leicester Castle.[45] He was, says Grosmont, equally guilty of the sin of lust, and admits—bitterly—to a passion for women, and especially for the "lecherous kisses" of ordinary women–"or worse, whom he liked all the more because, unlike good women, they would not think the worse of him for his conduct".[48] He admits to having taken advantage of his superior social position by extorting money from his tenants, and those "who need it most".[26]

Grosmont then describes the wounds in his soul as having been attacked: the seven deadly sins through his five senses, praying, each time, for a remedy appropriate to the sin.[49] But Grosmont's body is particularly porous: it gushes blood and tears, and wounds are not limited to seven, rather "all the body is so full of wounds."[50] In this way, suggests Arnould, each of his temporal, real-life experiences is given a spiritual equivalent.[49] For example, as a patient of Christ, Grosmont describes how he obtains a theriac[16][note 6] of treacle, which he states is "made of poison so that it can destroy other poisons".[53] When the treacle has done its work, the last necessity is a drink of "that rare and precious beverage, the milk of the Virgin Mary".[54]

Metaphors and similes

The whole book is effectively allegorical: so a wounded man needs a physician, so a sinner needs redemption. The metaphors Grosmont uses to describe his remedy—including food, drinks, potions, bandages—"sounds rather banal", comments Pantin, but, rather, is "a work of great freshness and simplicity".[55] The food, for example, is redeeming chicken soup and his bandages are Mary's Joys.[20] Grosmont remains focussed on his overarching theme, but this does not prevent him from digressing—"often deliberate, always conscious"—into intellectual philosophising or personal anecdotes[18] for which he regularly apologises. Grosmont makes full use of his active imagination in his use of language, using colourful and extravagant metaphors,[56] although many of which—the Virgin's milk as a balm against sin, for example—were established tropes in religious writing.[57] His senses are personalised.[58] His body is a castle, with the walls his hands and feet, while his heart is the donjon "where innocence makes its last stand".[56][note 7] A sow pregnant with seven offspring represent a worldly man bearing each deadly sin.[59] Other metaphors for his heart—the area he devotes to his most complex and ambitious imagery[60]—are a whirlpool, a foxhole and a public fair, or marketplace.[61] The foxhole analogy is of interest, suggests Labarge, as it may reflect events going on in Grosmont's life at the time he wrote the particular paragraph. From March to April 1354 Grosmont was in negotiation with Guy of Boulogne via the medium of "a highly sarcastic exchange of letters" regarding England's attempts to recruit Charles of Navarre as an ally against France; Guy—believing he had prevented it—wrote that he had "stopp[ed] a mousehole", to which Grosmont retorted that "a mouse that knew of only one hole was likely to be in danger".[36]

The governing conceit is that Lancaster's sins and the senses through which they enter are wounds which can only be healed once they have been bathed with the milk and tears of the Virgin, anointed with the blood from Christ's wounds, and bandaged with the Virgin's joys.[50]

These similes, argues Arnould, represent the hidden dangers of the sinful world, a place into which conscience is driven to corner sin, and a meeting place for the sins.[61] Other similes are from the animal world, for example, a cat represents the devil in his allegorical tale of a poor man who cleans his house thoroughly to make it worthy of his master who is coming to visit, and as such expels the cat from his best chair, but which—the moment the master has left—is allowed to return to the house and do as it will.[62] Martial imagery is also strong, for example the references to courts, castles, sieges, prisons, ransoms, vassalage, treason and safe conduct, as Kaeuper notes; on occasion he refers to God in the feudal language of '"Sire Dieu".[63] Other images are less obvious, for instance, Grosmont's assertion that a man's nose will give away whether or not he has been taking part in tournaments.[64][note 8]

In part, this loose structure was probably a direct result of the nature of its composition if, as has been surmised, that Grosmont wrote portions of it each day, dipping in and out of writing in between a myriad of other duties and responsibilities.[18]

The author

%252C_f.8_-_BL_Stowe_MS_594_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The son and heir of Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, and Maud Chaworth, Grosmont became one of King Edward III's most trusted captains in the early phases of the Hundred Years' War and distinguished himself with victory in the Battle of Auberoche.[66] A late 14th-century chronicler described him as "one of the best warriors in the world",[67] while Froissart calls him "a good knight" and a "valiant lord, wise and imaginative".[55] Thomas Grey, writing a few years after Grosmont, called the duke "wise, full of glory, and valiant, and in his youth eager for honour and feats of arms, and before his death, a fiercely devout Christian".[68] Several modern historians have agreed with this assessment;[42][note 9] Margaret Wade Labarge, for example, has called him "one of the outstanding figures of a reign which abounded in colourful chivalric personalities".[72] Grosmont, made Earl of Derby in 1337, Lancaster on his father's death in 1345[73] and a founding member and the second Knight of the Order of the Garter three years later. In 1351 he was created Duke of Lancaster, only the second such creation and the first non-royal dukedom.[74][note 10] He was the wealthiest and most powerful peer of the realm,[66] but, comments Janet Coleman, he was no scholar,[75] something Grosmont readily admits; while his discussion of things religious is broad, imaginative and wide-ranging, he himself points out that he deliberately avoids "profound matters".[76][note 11]

Piety

Grosmont was also religious,[78] and Rothwell calls Le Livre "a long, painful act of contrition".[58] Labarge argues that he was symbolic of the "more secular" 14th-century knight than his predecessor of the previous century, to whom crusading had still been a Holy state.[note 12] His piety appears occasionally throughout his military campaigns. For example, when the citizens of Bergerac begged for mercy in return for surrender in 1345, Henry replied "who prays for mercy shall have mercy". When an indecisive chevauchée took him almost to Toulouse,[81] Geoffrey the Baker's Chronicon describes how a Carmelite prior had "a silver banner with a picture in gold of the blessed virgin on it, and, amid a hail of missiles, he displayed the picture on his banner at the walls of the town and he caused the Duke of Lancaster and many of his army to kneel in devotion to it" in a spontaneous act of piety.[82] Conversely, argues Richard Kaeuper, there are "perhaps contradictions in Lancaster's piety", as his 1346 raid into Poitou was particularly bloody, and involved the burning of many churches,[83] demonstrating what Batt calls both "generous and unsparing... pitilessness as well as courtliness".[84] This was to the extent that when Pope Clement heard of Grosmont's sacking of Saint-Jean-d'Angély abbey—in which, as well as emptying the house of its valuables the monks were taken captive and held to ransom—Clement wrote to the earl asking him to restrain his men from attacking religious buildings or ecclesistics.[83]

Grosmont's patronage reflected formal, expected religious practice of the 14th-century nobility,[85] for example, by funding chantries in Lancaster.[78] The year after writing Le Livre he founded a college and refounded St Mary de Castro, [3][note 13] a college of secular canons at Leicester staffed by 30 monks with responsibility for the spiritual wellbeing of 100 poor persons,[78][note 14] with 10 female nurses to attend to their physical health.[87] Architectural historian John Goodall has suggested that in size the church was "magnificent and elegant", over 200 feet long.[87] According to Pantin, Grosmont was responsible for funding nearly 100 prebendaries and other precariae between 1342 and his death.[88] Grosmont's writings, however, argues Labarge, place him firmly in the milieu of "a new current of personal and emotional piety" who did not just read, but wrote,[85] and in Grosmont's case was not afraid of combining both his natural religious feelings with real-world, empirical experience.[85] He was not, says Pantin, "a leveller or a prude", as while accepting he was too fond of gorging himself, he recognised that that lifestyle was mandated for the aristocracy, if moderately, "according as their estate demands it".[26]

Life experiences in Le Livre

Labarge argues that the number and range of metaphors Grosmont uses are testament to the breadth of his life experience and knowledge. Specific examples include that salmon are not truly such until they have lived in the sea first, before swimming upstream for breeding purposes[14] (whereby sins are like salmon, which only become mortal when they reach the heart).[89] Spring is the optimum time to drink goat's milk because of the fresh herbs the animal will have eaten by then. He includes a recipe for cooking capon in a bain-marie,[90] what Batt calls "a classic recipe for chicken soup, necessary food for the convalescent" and the sinner also.[91] Grosmont also uses the metaphor of hunting—a traditional aristocratic pastime—as a way of fighting sin. He describes his confessor as a forester whose job is, metaphorically, to maintain a balance in the chase between the animals and predators, in which the body is the park, a man's virtues are the game, under constant threat of attack from vice.[92] He compares fighting in tournaments to Christ fighting the devil on behalf of mankind.[26] Surgeons at the University of Montpellier were donated the bodies of executed criminals for dissection and research purposes; Grosmont uses this as a means of expressing his wish that his soul could be so opened up to expose its sin. his knowledge of the dangers of the sea probably stemmed from his official role as Admiral of the West and his numerous naval voyages. The comparison of his heart to a city marketplace, where all roads led to and therefore where all sin ends up, was clearly a reflection of every town's market day.[14] Labarge describes how Grosmont

Makes us see the cooks and innkeepers incessantly crying their wares, the women better dressed than on Easter, the men drinking in the taverns and going to brothels while citizens and merchants brawled loudly. Meanwhile, the lord's officials inflexibly asserted his rights and collected the tolls while the sergeant, whom Henry compares to the devil, stood ready to carry out a distraint without mercy.[93]

One of the few occasions where Grosmont veers from real-life experience into medieval myth is in his description of curing frenzy[94] (probably delirium)[95] for which he prescribes the evisceration of a live cockerel which is then placed on the head of the patient; this is his metaphor for receiving the ointment of Christ's blood.[94][91] Grosmont also demonstrates an understanding of the limits of his suggestions; for example, although he advocates theriac as a poison to destroy other poisons, he is also aware that, if a patient is already poisoned too badly, the new poison will make things worse rather than better.[23] Grosmont would have been associated with medical practitioners of varying degrees of expertise, from battlefield surgeons to court physicians, and his use of medical imagery indicates he learned much from them.[96] During his 1356 Siege of Rennes, for example, the French captain Olivier de Mauny entered the English camp, badly wounded; Grosmont saw to it that his surgeons gave him the best treatment and "healing herbs" they could.[95] It is curious, suggests Batt, that with all Grosmont's life experience, his piety and all the religious foundations he has by now accomplished, that at no point does he refer directly to his personal, real-life religion, never mentioning, for example, his holy thorn or St Mary's Newarke,[97] or even his family or friends.[98] Likewise it is likely that some of his information—such as how to determine the freshness of a pomegranate —came not from experience but from contemporary works, such as a dietary.[95]

Historical context

Written in Anglo Norman[38] —the French dialect of medieval England[99]—the Livre[note 15] tells historians something as to Duke Henry's own upbringing and personality through his own words. He says he was a good looking youth, for example, but, as he was English, knew little French, and the learning that he had, had come to him late in life.[4] Although Fowler comments that "on the latter point he was modest about his own accomplishment",[4] Tavormina argues that this was not necessarily to be taken literally, as a number of similar expressions of self-apology are found in other contemporaneous texts and should be seen as intentional humility.[6] On the other hand, suggests Batt, the breadth of his observations may include references to the Divine Comedy, and even if not, Le Livre "is clearly the work of a well-read and cultured author".[100] Coleman suggests there is a tension between the admiration Grosmont had for the French language—being "respectful, rather humble" towards it—and his career as a great fighter in France against all things French.[75]

Grosmont may have been influenced by othern writers, such as Guillaume de Deguileville, whose treatment of the Lady Sloth character is similar to his,[101] and even though he is not known to have possessed many books, he probably had access to Leicester Abbey's[102] extensive library, which included over eighty medical books.[103] Batt suggests that the lack of direct influence is useful in itself as a historical reference point as, having "no obvious identifiable single source",[23] it sheds direct light on Grosmont's activities—more precisely, his view of his activities—over the preceding decade.[81] Although Le Livre rarely touches on chivalry,[104] Arnould has noted a stark difference in the Grosmont known to contemporaries and thence to historians—the great general, diligent royal servant and epitome of chivalry—and the one he presents himself, "so ingenuously humble and sometimes crudely frank".[42] He also displays qualities of tenderness, dignity and "gentle candour" through his writing.[48] These qualities are not, however, incompatible, argues Arnould, as the piety the author demonstrates combined with a lack of animosity towards enemies may back up the chivalric image rather than impinge upon it.[42] Batt argues that Grosmont personifies the contradictions inherent in the medieval chivalric ideal vis-à-vis the warrior knight and the penitent Christian.[105] The book also suggests the extent of Grosmont's own medical knowledge, and more broadly the extent to which continental expertise had impacted England; Grosmont's personal physician was from Bologna, for example. New medical concepts entwined with traditional religion as well; a confessional text from Exeter of 1340, for example, uses a similar metaphor to Grosmont, proposing that "Christ is the best physician".[106] Grosmont also points out that wisest of physicians, as such is Christ, will not waste his precious medicine on the incurable.[107]

Audience and legacy

Janet Coleman has pointed out that by this period, the English nobility was reading for both edification and pleasure,[75] and Tavormina notes that the work's readership would have to be learned in French, which would have comprised the educated nobility,[2] lawyers, ecclesiastics and upper-middle-classes:[38] "a small religious elite", says linguist William Rothwell, and as such a very limited audience.[58] It is one of the few devotional treatises which addresses the reader as well as the author; most of the period tended to be directed at the latter as if from an unknown superior. Le Livre, though, is as conscious of the author's sins as his audience's.[108] Le Livre may have been a direct influence on John Gower's Mirour de l'Omme of later in the century; both are directed primarily to an English social class who had the financial and social independence to control their own regious activity.[109]

Grosmont, notes Tavormina, "was remembered as the author of a devotional treatise for at least a century after his death".[38] Mary de Percy, widow of John, Lord Ros, left a copy to Isabel Percy in 1394. Mary was connected to Grosmont through her father, whose first wife—not Mary's mother— was Grosmont's younger sister. This is not, however, the copy that descended through to Duke Humphrey, as that was presented to him by Thomas Carew, who died in 1429.[110][111] The same copy appears to have been previously owned by John de Grailly, Captal de Buch, as both his and Humphrey's armorials are inscribed on various pages.[27]

Another reference to Le Livre comes in 1400, in the catalogue of Titchfield Abbey library, although this copy appears not to have had the title it was given by Grosmont, or indeed any other colophon.[112] Later medieval historians drew clear links between Grosmont's political activity, and importance, and his piety. The chronicler Thomas Walsingham, for example, describes Grosmont as symbolically supporting his grandson's accession to the throne in 1399 by supposedly writing him a letter recounting the benefits of a chrism—which the author claimed to have brought back from the Holy Land—to new kings. In Batt's words, Walsingham "seamlessly links the divine and the political", with Grosmont the denominator. Thomas Otterbourne, writing around 1420, uses Grosmont as a trope for opening his own treatise, by explaining how the duke begs for mercy for his sins while simultaneously giving thanks for the good things he has enjoyed along the way.[113] A late 14th century redaction of Edmund of Abingdon's Mirour de Seinte Eglyse also aligns Grosmont's piety with his wealth and power:

Þou þat neuere seȝe Duyk Henri,

Þat þe newe werk of Leycetre reised on hiȝ:

Þer-þi maiȝt þou wel wyte and se

Þat he was lord of gret pouste [power]

Þat hit made of his ownc cost—

I hope he naue þeron not lost.[114]

Grosmont's college in Leicester (the "new werke", also a play on its location) is used as an example of his earthly power and wealth, which the poet then explains has been turned, on Grosmont's death, into spiritual wealth ("I hope he naue þeron not lost").[115]

Scholarly history and reception

Grosmont's Livre was originally produced in 26 folios, at least one of which was a family copy as denoted by his armorial decorating page borders; this version ended up—Maya, Mexica—in the extensive library of his great-grandson Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester.[6] Copies may have been made in Grosmont's lifetime.[22] Two entire copies are known of in the 21st century, one held at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and the other at Stonyhurst College, Lancashire. The substantive contents of both are identical, with only minor linguistic differences separating them.[116] The Stonyhurst MS is the earliest, and also the most decorated with numerous coats of arms;[117] that of Cambridge, while looking more modest, says Batt, has an "elegant blue animal skin chemise binding".

[Grosmont] suffers from seven perilous wounds in his ears, eyes, nose, mouth, hands, feet, and heart through which the seven deadly sins, like enemies breaching a castle, have entered his body (soul). His heart, moreover, he compares to the sea, a fox's hole, and a market-place to show its wickedness. Like a sick man, therefore, he seeks a physician, in this case, Jesus. The remedies, too, are allegorical. To take but one example, he compares his sinfulness to poisoning and spins out an allegory based on antidotes to venom. The medicines to cast out the venomous sin are saintly sermons, good lessons, and true examples received through his ears from good men and good books.[78]

The Livre had never been published until Henry Arnould's 1940 edition, which he based primarily on the Stonyhurst copy but compiled after examination of both that and the Cambridge copy.[22] Arnould had intended for his edition to be accompanied by an extensive introduction, but this had to be curtailed on account of World War II breaking out in September 1939.[119][note 16] Although Arnould promised a far fuller introduction than he was forced to provide, this did not appear until 1948, in French and published in Paris, and as such without the momentum of the original edition.[120][note 17] Rothwell argues that medievalists will not find Arnould's description of Grosmont's life providing anything new to the field, or "have scant concern with the following hundred pages dealing in minute detail with the phonology, morphology, and a few syntactical points relating to the language".[120][note 18]

Le Livre offers, argues Arnould, "an allegorical, but autobiographical, account of Henry's sins and penances".[123] Arnould had argued in 1937 that it was odd that the Livre—"the author of which is also one of the most prominent men of his time—should have hitherto passed unnoticed".[124] He compares its "picturesque style" with that of St Francis de Sales,[125] while Ackerman has suggested that, with its "engaging, anecdotal charm" it is close to the spirit of the Ancrene Riwle,[15] which Grosmont probably knew of, either in English or French.[126] The historian Scott L. Waugh has contextualised the Livre as being part of an "intense" lay involvement in religious affairs in the mid-14th century, more obviously seen in the building of chantries and chapels by the former for the latter. But the Livre, says Waugh, is "the most spectacular evidence" historians have for this phenomenon. Waugh notes that, while his patronage of the church was extremely generous, it was also a conventional expression of piety: "his Livre was not."[78] McFarlane has argued that the Livre indicates the existence, in the nobility, of a class who were not only active in their traditional roles—warfare, royal service, estate management, for example—possessed "quite remarkable versatility, accomplishments and taste", and casts further light—"a third dimension"—on historians' knowledge of the intellectual activities and abilities of the English aristocracy.[127]

Richard Kaeuper argues that—as its ownership by men such as de Grailly suggests—it was highly valued in the chivalric world.[27] He also argues that the book demonstrates Grosmont's belief in the efficacy of imitating Christ through the martial life, not just in the sacrifices it forces one to make but as a form of penance.[65] It is notable in Pantin's view for discussing Christology from the perspective of the layman rather than the professional.[128] Conversely, Andrew Taylor has argued that Grosmont demonstrates a tendency to be refractory in his recital of his own sins, perhaps suggesting that rejects absolute humility, even before Christ: "for all his religious instruction, [Grosmont] remained perversely attached to his own sinful body".[129] Labarge suggests that its importance to historians lies not so much in its colourful symbolism but Grosmont's extensive, and detailed, use of his own personal experiences to illustrate his message.[45] In its literary value, it has been compared—as a "valuable analogue"—to better-known works with similar messages such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.[130] Indeed, it has been suggested that Grosmont is an "outstanding candidate" of patron to the Gawain's now-anonymous author—and the basis for the eponymous hero—as the poem "would have appealed to every facet of Henry's complex character".[131][note 19]

Grosmont's work is also important, argues Catherine Batt, for what it says about the extent and knowledge of medieval medical knowledge. While predominantly metaphorical and allusional—Christ the doctor, Mary the nurse—it also reflects the practical medical knowledge of its author (for example, the practical efficacy of herbs in the springtime).[133] This knowledge, she suggests, shaped his overall philosophy and religion.[23] Batt also argues, however, that there are elements of what to modern perception are found in a situation comedy, particularly in the character sloth, which she calls "arguably the most engaging of Henry's projections of his own sinful self". Lady Sloth is portrayed as taking advantage of an honourable man by getting herself invited in—when no man of honour would turn a lady at his gate away—and then abusing his hospitality.[134] That Grosmont is confessing to being a practitioner of her vice makes him more receptive to it and so makes it easier for her to stay.[135]

Sloth comes to the gate of the ear and begs to be let in, because she is very sick, and says that just as soon as she has rested a little while she will go; and she does so much that she gets in, and once she is here she goes to bed and falls asleep. And should anyone come to the gate and say: ‘I am a friend of Lady Sloth, let me come in to comfort her’, the gate will be very quickly opened to let in one of her friends, who is then eager to comfort Sloth by saying: ‘Lady, don't worry about anything at all, except your comfort, and especially the comfort of the body; and we shall think about the soul some other day, when we are old and shall have nothing else to do.[134]

Christopher Fletcher, discussing what Le Livre tells of the role of the nobility—and especially the martial nobility—in religion, argues that it is probably one of the few works of the period to address the contradiction between the secular and the ecclesiastic in religion. Le Livre, says Fletcher, raises the question as to who is the better Christian: "the priest, who is a man, but who can neither marry nor shed blood? Or a nobleman, who knows what it is to be a good Christian—thanks to his confessors, preachers and his own upbringing—but who lives in a competitive and violent world, and who desires other women than his wife?"[136]

Further fragments discovered

A further 26 fragmentary folios of Grosmont's work were identified as belonging to Le Livre in the early 1970s, in a National Library of Wales manuscript[22] previously thought—thanks to being "carelessly and systematically misbound"[137] around the end of the 17th century[115]—to be a 15th-century medical treatise.[22] It is not known precisely when it entered the university's possession, but it was part of the Hengwrt-Peniarth collection when William Wynne catalogued it in 1864.[138][note 20] Written on vellum, it contains several passages known in the extant Livre as well as a number of Lacunae, and while the fragment shows many differences in spelling and grammar from the other two, it does not contain new material.[22] This may indicate that Le Livre had a broader audience than has previously been assumed.[139]

Extant manuscripts

- Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales, Peniarth, 388 c 2, p. 1-52.

- Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Parker Library, 218, f. 1ra-68ra.

- Hatfield, Hatfield House, Cecil Papers, 312.

- Hurst Green, Stonyhurst College, 24 (HMC 27), f. 1ra-126ra.

Notes

- ↑ There were others, including Grosmont's contemporary Geoffroi de Charney—"with whom Henry has much in common in terms of both devotional practice and religious observance"—who was killed at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 and authored Le Livre de Chvalerie,[7] Edward, Duke of York, who wrote a hunting treatise in the early 15th century[8] and James I of Scotland with his The Kingis Quair,[9] although Grosmont's is the longest original piece of work.[6]

- ↑ In this context, simples were medicines made out of a single ingredient rather than a compound.[24]

- ↑ Batt notes that as of 2014 she had never come across another example of a reverse signature such as Grosmont uses, although occasionally simpler forms are found, for example, Robert being transposed as Trebor.[32]

- ↑ Although it is perhaps curious, suggests Batt, that he never names them.[35]

- ↑ Douce Dame is a reference to the Douce Dame Jolie ("Sweet, Lovely Lady"), a motif in the 14th-century songs of Guillaume de Machaut.[43] The Virgin Mary was also a figurative Douce Dame, sitting at the side of Christ,[44] and this is the context Grosmont uses the phrase.[45]

- ↑ Theriac was a medical concoction that had made its way from the East to the West via the trading links of the Silk Route.[51] It was an alexipharmic, or antidote, considered a panacea,[52] Theriac was expensive, but a homegrown version-treacle-was readily available and considered to have similarly cathartic properties.[53]

- ↑ The donjon as a metaphor for the heart was a common medieval literary device.[45]

- ↑ This, argues Kaeuper, is because a man's nose may be broken in a tourney, and likewise mouths "beaten and twisted out of shape", reflecting the wounds Christ received during his flagellation.[65]

- ↑ For example, Clifford J. Rogers calls him a "superb and innovative tactician";[69] Alfred Burne, "brilliant";[70] and Nicholas Gribit "stunning".[71]

- ↑ The only previous ducal creation was that of King Edward's son the Black Prince to that of Cornwall; David Crouch comments that, while cousins, Grosmont's "distance from the throne was sufficient to reckon him as the first non-royal duke".[74]

- ↑ In spite of this, at least by the 15th century, Grosmont was also credited with the authorship of the now-lost Livre des Drois de Guerre.[77]

- ↑ This belief had been weakened, argues Labarge, as a result of the "series of ignominious defeats" the crusading armies had suffered in the Holy Land, as well the blatantly political crusades[79]—such as France's invasion of Castille or the papacy's campaign against Frederick the Great[80]—of the later years of the century, all of which contributed to the image of the crusading knight being tarnished. By Grosmont's time, it was as much a sound strategy for financial or political reasons as a religious ideal. [79]

- ↑ Originally founded by Grosmount's father in 1330.[20]

- ↑ To which he granted a relic he had been given by King John II of France—a thorn from Christ's crown—following a tournament in 1352.[86]

- ↑ So-called because of the colophon to the text body.[38]

- ↑ Indeed, by the time Arnould got to write the brief introduction he did, he had already, in his words, "answered the call to arms" and signed the proofs off with "somewhere in France, 23 December 1939".[119]

- ↑ Published by Didier as E. J. Arnould Etude sur le Livre des Saintes Médecines du Duc Henri de Lancastre: Accompagné d'Extraits du Texte (Paris, 1948).[121]

- ↑ Rothwell's underlying point, however, is that this—and the concomitant lack of interest from scholars of French or literature—is indicative of over-compartmentalisation between subject areas rather than a reflection on either the original work or Arnould's edition.[122]

- ↑ This is due to the events of Gawain being traditionally viewed as taking place in the northwest Midlands, where Grosmont had a concentration of estates, being active at the same time as Gawain is generally thought to be composed, Grosmont's self-identification and adherence to the chivalric code, and of course his known literary ability as seen from Le Livre.[132]

- ↑ Wynne also was unsure of the exact nature of the manuscript, and catalogued it as "Fragment of a French M.S. of the fifteenth century—Query, upon religion or medicine—not easy to make out the abbreviations, and some of the letters".[138]

References

- ↑ Parker 2020.

- 1 2 Yoshikawa 2009, p. 397.

- 1 2 Batt 2014, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Fowler 1969, p. 26.

- ↑ Batt 2006, p. 407.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tavormina 1999, p. 20.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 8.

- ↑ Baillie-Groham & Baillie-Groham 2005, p. xi.

- ↑ Mooney & Arn 2005, pp. 17–112.

- ↑ McFarlane 1973, p. 242.

- ↑ Pantin 1955, p. 107.

- 1 2 Gransden 1998, p. 62.

- 1 2 Arnould 1937, p. 354.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Labarge 1980, p. 188.

- 1 2 Ackerman 1962, p. 114.

- 1 2 Arnould 1937, p. 370.

- ↑ Goodman 2002, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arnould 1937, p. 367.

- ↑ Boyson 2017, p. 168.

- 1 2 3 Batt 2014, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Arnould 1937, p. 353.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Krochalis & Dean 1973, p. 87.

- 1 2 3 4 Batt 2006, p. 409.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 35.

- ↑ Taylor 1994, p. 116 n.2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pantin 1955, p. 232.

- 1 2 3 Kaeuper 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Fowler 1969, p. 195.

- ↑ Arnould 1940, p. viii.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 48.

- ↑ Legge 1971, pp. 218–219.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 282 n.588.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 280.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 12.

- ↑ Batt 2014, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 3 Labarge 1980, p. 186.

- ↑ Tavormina 1999, pp. 20–21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tavormina 1999, p. 21.

- ↑ Taylor 1994, p. 113.

- 1 2 Yoshikawa 2009, p. 398.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 282.

- 1 2 3 4 Arnould 1937, p. 364.

- ↑ Wilkins 1979, pp. 20–22.

- ↑ O'Sullivan 2005, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 4 Labarge 1980, p. 187.

- ↑ Arnould 1937, p. 383.

- ↑ Arnould 1937, pp. 383–384.

- 1 2 3 Arnould 1937, p. 384.

- 1 2 Arnould 1937, pp. 364–365.

- 1 2 Taylor 1994, p. 103.

- ↑ Boulnois 2005, p. 131.

- ↑ Griffin 2004, p. 317.

- 1 2 Cantor 2015, p. 174.

- ↑ Arnould 1937, p. 373.

- 1 2 Pantin 1955, p. 231.

- 1 2 Arnould 1937, p. 368.

- ↑ Batt 2014, pp. 53–54.

- 1 2 3 Rothwell 2004, p. 316.

- ↑ Badea 2018, p. 6.

- ↑ Ackerman 1962, p. 116.

- 1 2 Arnould 1937, p. 374.

- ↑ Arnould 1937, p. 382.

- ↑ Kaeuper 2009, p. 39.

- ↑ Arnould 1937, pp. 382–383.

- 1 2 Kaeuper 2009, p. 41.

- 1 2 Ormrod 2004.

- ↑ Rogers 2004, p. 89.

- ↑ King 2005, p. 196.

- ↑ Rogers 2004, p. 107 n.61.

- ↑ Burne 1949, p. 117.

- ↑ Gribit 2016, p. 22.

- ↑ Labarge 1980, p. 183.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 3.

- 1 2 Crouch 2017, p. 206.

- 1 2 3 Coleman 1981, p. 19.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 32.

- ↑ Taylor 2009, p. 67 n.16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Waugh 1991, p. 139.

- 1 2 Labarge 1980, pp. 183–184.

- ↑ Duffy 2014, p. 156.

- 1 2 Labarge 1980, p. 185.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 68.

- 1 2 Kaeuper 2009, p. 234 n.2.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Labarge 1980, p. 184.

- ↑ Labarge 1980, pp. 185–186.

- 1 2 Batt 2014, p. 39.

- ↑ Pantin 1955, p. 49.

- ↑ Taylor 1994, p. 104.

- ↑ Labarge 1980, p. 189.

- 1 2 Batt 2006, p. 411.

- ↑ Badea 2018, p. 9.

- ↑ Labarge 1980, pp. 188–189.

- 1 2 Labarge 1980, p. 190.

- 1 2 3 Batt 2014, p. 37.

- ↑ Yoshikawa 2009, p. 401.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 11.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 50.

- ↑ Coleman 1981, p. 20.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 34.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 52.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 59.

- ↑ Page 2013, p. 28.

- ↑ Barnie 1974, p. 63.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 5.

- ↑ Yoshikawa 2009, pp. 400–401.

- ↑ Batt 2014, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Fletcher 2015, p. 55.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 61.

- ↑ Krochalis & Dean 1973, p. 91.

- ↑ Yoshikawa 2009, p. 397 n.1.

- ↑ Krochalis & Dean 1973, p. 92.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 7.

- ↑ Batt 2014, pp. 56–57.

- 1 2 Batt 2014, p. 57.

- ↑ Arnould 1937, pp. 352, 353.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 14.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 16.

- 1 2 Arnould 1940, p. vi.

- 1 2 Rothwell 2004, p. 317.

- ↑ Rothwell 2004, p. 317 n.30.

- ↑ Rothwell 2004, p. 318.

- ↑ Bartlett & Bestul 1999, p. 14.

- ↑ Arnould 1937, p. 352.

- ↑ Arnould 1992, p. 673.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 26.

- ↑ McFarlane 1973, pp. 47, 242.

- ↑ Pantin 1955, p. 233.

- ↑ Taylor 1994, p. 115.

- ↑ Fletcher 2015, p. 54.

- ↑ Cooke & Boulton 1999, p. 46.

- ↑ Cooke & Boulton 1999, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Batt 2006, pp. 407–408, 411.

- 1 2 Batt 2010, p. 26.

- ↑ Batt 2010, p. 28.

- ↑ Fletcher 2015, p. 69.

- ↑ Batt 2016, p. 59 n.22.

- 1 2 Krochalis & Dean 1973, p. 90.

- ↑ Batt 2014, p. 58.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, R. W. (1962). "The Traditional Background of Henry of Lancaster's 'Livre'". L'Esprit Créateur. 2: 114–118. OCLC 1097339777.

- Arnould, E. J. F. (1937). "Henry of Lancaster and his 'Livre des Seintes Medicines'". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 21 (2): 352–386. doi:10.7227/BJRL.21.2.3. OCLC 1017181361.

- Arnould, E. J. F. (1992). "Henri de Lancastre". In Grente, G. (ed.). Dictionnaire des Lettres Françaises (in French). Vol. I: Le Moyen Âge. Paris: Librairie Générale Française. p. 673. ISBN 978-2-21359-340-1.

- Badea, G. (2018). "La Chasse Vers l'Inconscient: Métaphores Cynégétiques de la Confession dans Le Livre de Seyntz Medicines". L'Animal: Une Source d'Inspiration dans les Arts. Paris: Éditions du Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques. pp. 117–131. ISBN 978-2-73550-881-5.

- Baker, G. le (2012). Barber, R. (ed.). The Chronicle of Geoffrey Le Baker of Swinbrook. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-691-9.

- Barnie, J. (1974). War in Medieval English Society: Social Values in the Hundred Years War, 1337-99. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-40865-6.

- Bartlett, A. C.; Bestul, T. H., eds. (1999). "Introduction". Cultures of Piety: Medieval English Devotional Literature in Translation. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-0-80148-455-1.

- Batt, C. (2006). "Henry, Duke of Lancaster's Book of Holy Medicines: The Rhetoric of Knowledge and Devotion". Leeds Studies in English. (n.s.). 47: 407–14. OCLC 605082614.

- Batt, C. (2010). "Sloth and the Penitential Self in Henry, Duke of Lancaster's Le Livre de seyntz medicines / The Book of Holy Medicines". Leeds Studies in English. 41: 25–32. OCLC 1076662979.

- Batt, C. (2016). "Foul Fiends and Dirty Devils: Henry, Duke of Lancaster's Book of Holy Medicines and the Translation of Fourteenth-Century Devotional Literature". In Fresco, K. L. (ed.). Translating the Middle Ages (repr. ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 55–64. ISBN 978-1-31700-721-0.

- Boulnois, L. (2005). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books. ISBN 978-9-62217-824-3.

- Boyson, R. (2017). Goulbourne, R.; Higgins, D. (eds.). Jean-Jacques Rousseau and British Romanticism: Gender and Selfhood, Politics and Nation. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 187–208. ISBN 978-1-47425-068-9.

- Burne, A. (1949). "Auberoche, 1345: A Forgotten Battle". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 27: 62–67. OCLC 768817608.

- Cantor, N. F. (2015). In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World It Made. London: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-47679-774-8.

- Coleman, J. (1981). Medieval Readers and Writers, 1350-1400. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09144-100-5.

- Cooke, W. G.; Boulton, J. D. d'A. (1999). "'Sir Gawain and the Green Knight': A Poem for Henry of Grosmont?". Medium Ævum. 68 (1): 42–54. doi:10.2307/43630124. JSTOR 43630124. OCLC 67118740.

- Crouch, D. (2017). Medieval Britain, c.1000-1500. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52119-071-8.

- Duffy, E. (2014). Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes (3rd ed.). London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-20708-8.

- Fletcher, C. D. (2015). "Masculinité et religion chrétienne dans le Livre de Seyntz Medicines de Henri de Grosmont, duc de Lancastre " de Henri de Grosmont, duc de Lancastre". Cahiers Électroniques d'Histoire Textuelle du Lamop. Genre Textuel, Genre Social. 8: 51–69. OCLC 862850547.

- Fowler, K. A. (1969). The King's Lieutenant: Henry of Grosmont, First Duke of Lancaster, 1310–1361 (1st ed.). New York: Barnes & Noble. OCLC 164491035.

- Goodman, A. E. (2002). Margery Kempe: And her world. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31787-929-9.

- Gransden, A. (1998). Historical Writing in England: c. 1307 to the Early Sixteenth Century (repr. ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41515-237-2.

- Gray, T. (2005). King, A. (ed.). Sir Thomas Gray: Scalacronica (1272-1363). Woodbridge: Surtees Society. ISBN 978-0-85444-079-5.

- Gribit, N. (2016). Henry of Lancaster's Expedition to Aquitaine 1345–46. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-78327-117-7.

- Griffin, J. P. (2004). "Venetian treacle and the Foundation of Medicine's Regulation". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. Wiley. 58 (3): 317–25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02147.x. OCLC 652432642. PMC 1884566. PMID 15327592.

- Grosmont, Henry of (1940). Arnould, H. E. J. (ed.). Le Livre de Seyntz Medicines (1st ed.). Oxford: Anglo-Norman Text Society. OCLC 187477897.

- Kaeuper, R. W. (2009). Holy Warriors: The Religious Ideology of Chivalry. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-81224-167-9.

- Krochalis, J.; Dean, R. J. (1973). "Henry of Lancaster's Livre de Seyntz Medicines: Fragments of an Anglo-Norman Work". National Library of Wales Journal. 18: 87–94. OCLC 1000744447.

- Labarge, M. W. (1980). "Henry of Lancaster and Le Livre de Seyntz Medicines". Florilegium. 2: 183–191. doi:10.3138/flor.2.010. OCLC 993130796.

- Lancaster, Henry of Grosmont, Duke of (2014). Batt, C. (ed.). The Book of Holy Medicines. Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. ISBN 978-0-86698-467-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Legge, M. D. (1971). Anglo-Norman literature and its Background (repr. ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 466274508.

- McFarlane, K. B. (1973). The Nobility of Later Medieval England: The Ford Lectures for 1953 and Related Studies. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19822-657-4.

- Norwich, Edward of (2005). Baillie-Groham, W. A.; Baillie-Groham, F. N. (eds.). The Master of Game (repr. ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-81221-937-1.

- O'Sullivan, D. E. (2005). Marian Devotion in Thirteenth-century French Lyric. -Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-80203-885-2.

- Ormrod, W. M. (2004). "Henry of Lancaster, First Duke of Lancaster (c.1310–1361)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12960. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Page, S. (2013). Magic in the Cloister: Pious Motives, Illicit Interests, and Occult Approaches to the Medieval Universe. Philadelphia: Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-27106-297-6.

- Pantin, W. A.l (1955). The English Church in the Fourteenth Century: Based on the Birkbeck Lectures, 1948. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 1477599.

- Parker (2020). "Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 218: Henry, Duke of Lancaster, Le livre des Seintes Medicines". Parker Library On the Web – Spotlight at Stanford.

- Rogers, C. J. (2004). Bachrach, B. S.; DeVries, K.; Rogers, C. J. (eds.). "The Bergerac Campaign (1345) and the Generalship of Henry of Lancaster". Journal of Medieval Military History. II: 89–110. OCLC 51811459.

- Rothwell, W. (2004). "Henry of Lancaster and Geoffrey Chaucer: Anglo-French and Middle English in Fourteenth-Century England". The Modern Language Review. 99 (2): 313–327. doi:10.2307/3738748. JSTOR 3738748. OCLC 803462593.

- Scotland, James I of (2005). Mooney, L. R.; Arn, M. (eds.). The Kingis Quair and Other Prison Poems. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 978-1-58044-093-6.

- Tavormina, M. T. (1999). "The Book of Holy Medicines". In Bartlett, A. C.; Bestul, T. H. (eds.). Cultures of Piety: Medieval English Devotional Literature in Translation. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 19–40. ISBN 978-0-80148-455-1.

- Taylor, A. (1994). "Reading the body in Le livre de seyntz medecines". Essays in Medieval Studies. 11: 103–118. OCLC 641904494.

- Taylor, C. (2009). "English Writings on Chivalry and Warfare during the Hundred Years War". In Coss, P. R.; Tyerman, C. (eds.). Soldiers, Nobles and Gentlemen: Essays in Honour of Maurice Keen. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 64–84. ISBN 978-1-84383-486-1.

- Waugh, Scott L. (1991). England in the Reign of Edward III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52132-5103.

- Wilkins, N. (1979). Music in the age of Chaucer. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-052-1.

- Yoshikawa, N. K. (2009). "Holy Medicine and Diseases of the Soul: Henry of Lancaster and Le Livre de Seyntz Medicines". Medical History. 53 (3): 397–414. doi:10.1017/S0025727300003999. OCLC 66411641. PMC 2706570. PMID 19584959.