Lee Bong-chang | |

|---|---|

Lee after his 1932 arrest | |

| Born | August 10, 1900 |

| Died | October 10, 1932 (aged 32) Ichigaya Prison, Tokyo, Empire of Japan |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Resting place | Hyochang Park 37°32′43″N 126°57′41″E / 37.545390°N 126.961472°E |

| Awards | Order of Merit for National Foundation, 2nd grade |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 이봉창 |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | I Bong-chang |

| McCune–Reischauer | Yi Pongch'ang |

Lee Bong-chang (Korean: 이봉창; August 10, 1900 – October 10, 1932) was a Korean independence activist. In Korea, he is remembered as a martyr due to his participation in the 1932 Sakuradamon incident, in which he attempted to assassinate the Japanese Emperor Hirohito with a grenade.

Early life

Lee was born on August 10, 1900, in Hyochang-dong, Yongsan District, Seoul, Korean Empire.[1] He was born into the Jeonju Yi clan, to father Lee Chin-ku.[lower-alpha 1] He had an older brother, Lee Pŏm-t'ae.[2][lower-alpha 2]

His family was so poor that as soon as he graduated from elementary school, he began working. Around 1917, he worked in a shop owned by a Japanese person, but was fired in 1919.[2] In 1920,[2] he worked as an apprentice railroad engineer. However, as an ethnic Korean, he received poor pay and was not promoted for years. He decided to move to Japan to seek better opportunities, and resigned from his job in April 1924.[1][2]

In September 1924, he founded and led an anti-Japanese resistance group.[2][lower-alpha 3]

Move to Japan

He and his brother arrived in Osaka, Japan in November 1925.[1][2] He worked at an ironworking factory and was taken in by a Japanese family. He also took on the Japanese name Kinoshita Shoichi (木下昌一). He had hoped to receive better treatment as a "New Japanese" (「신일본인」) person, but was instead initially discriminated against. However, he learned to blend in and lived relatively comfortably.[1]

In 1928, Lee heard that the new Japanese Emperor Hirohito was to be crowned in November of that year. He thought that, as a New Japanese, he should see the face of his Emperor, and decided to go to Kyoto to see the ceremony. However, while there, he was arrested and detained for eleven days because he had a letter from a friend in his pocket that had Korean writing on it. This experienced shocked him. He reflected on what "New Japanese" even meant, and decided that he was really a Korean.[1]

Lee decided that if a proper leader for the independence movement emerged, he would follow them. But he gradually abandoned this idea, as he worked and lived in Japanese society. He distanced himself from everything Korean, including his relatives. He obtained work as a soap wholesaler by February 1929, by lying that he was Japanese to the store owner. But one day he witnessed a Korean customer being scolded for being unable to speak Japanese fluently. He suddenly felt ashamed that he had done nothing but watch as it had happened. He moved to Tokyo in October 1929 and worked odd jobs, then returned to Osaka in November 1930 and could not find work.[1]

After this, he decided to join the independence movement. He wanted to stop pretending to be Japanese and going by pseudonyms, and to embrace being a Korean.[lower-alpha 4] On December 6, 1930, he boarded a ship in Chikko, Osaka, and departed for Shanghai, one of the hubs for independence activists in exile.[1]

To Shanghai and the independence movement

Lee arrived in Shanghai on December 10, 1930.[1][2] He wanted to become economically stable before joining in with the independence movement. After spending two to three days in an inn, he went out to find work. But even after a month of searching, he could not find anything and was nearly completely broke. He stayed in the house of a Japanese tailor for free. Meanwhile, he asked around for information on where the Korean Provisional Government (KPG) could be, in hopes that they could help him find a job. He eventually learned from a ticket inspector the location of the Shanghai Korean Residents Association (SKRA), which happened to be secretly harboring the KPG at that time.[1]

In early January 1931, he visited the office of the SKRA and asked to join the KPG.[1][2] But he unintentionally used a Japanese term for the group,[lower-alpha 5] which made them suspect that he was a spy.[3][1] Prominent KPG member Kim Ku heard the commotion and came down to investigate. Kim introduced himself using a pseudonym. Lee repeated his story, but Kim too viewed Lee with suspicion. Kim gave vague and noncommittal answers, and agreed to speak with him again another day.[1]

A few days later, Lee visited the office again, this time bringing noodles and alcohol. A few Koreans there sat down with him. After the drinking started, he raised his voice and asked the table: "If it's so easy to kill the Japanese emperor, why haven't Korean independence activists done it yet?"[lower-alpha 6] The table responded skeptically and coldly, asking "If it's so easy, why haven't you done it?"[lower-alpha 7] Lee replied, "One day when I was in Tokyo, I heard that the Emperor was going to visit Hayama,[lower-alpha 8] so I went to go see him. He passed right in front of me, and I immediately thought, 'What if I had a gun or bomb with me right now?'"[1][lower-alpha 9]

Kim had been eavesdropping on their conversation from the second floor. Realizing that Lee had promise for a mission, Kim went to where Lee was staying in the evening. The two had an open conversation. Lee told Kim:[1][lower-alpha 10]

I am thirty-one years old.[lower-alpha 11] Even if I were to live another thirty-one years, how enjoyable would old age be compared to the free-spirited life I had previously? If the purpose of life is pleasure, I have tasted enough of it already; I came to Shanghai to work for the independence movement in order to obtain eternal pleasure.

Kim later wrote that this conversation moved him to tears, and that he agreed to put Lee to work in the independence movement.[1]

Preparing for the attack

Lee agreed to continue pretending to be Japanese while covertly training to become a guerrilla. Through the connections of Kim, Lee found an ironworking job, and eventually achieved a degree of economic stability.[1]

Lee and Kim Ku met a number of times afterwards to plan the attack. Meanwhile, Kim worked on acquiring weapons for the attack, but progress was slow due to the financial difficulties and political issues that plagued the KPG. In May, Lee asked Kim if he could join the KPG or any similar organization, but Kim declined, saying the organizations weren't worth joining because of their instability and weakness. This conversation, as well as the Wanpaoshan Incident that Japan used to stir up racial tension between Koreans and Chinese people, convinced Kim to create the Korean Patriotic Organization (KPO).[1]

Lee and Kim met less frequently after that: once every three or four months. Each time Lee came around, he brought food and alcohol. Lee became intoxicated a number of times and loudly sang songs in Japanese, which drew the ire of onlookers. Lee was also once chased off by Chinese guards because he was dressed like a Japanese person. Members of the KPG reprimanded Kim for bringing on someone who was so difficult to distinguish from a Japanese person, but Kim defended Lee each time. Around the end of August, Lee was asked to quit his job by his manager. His pay had been poor, and his motivation to work had been dropping. He stayed for ten days at the Japanese tailor's house again, and pressed Kim for the grenades so he could go to Japan. Preparations finally concluded by November.[1]

Leaving Shanghai

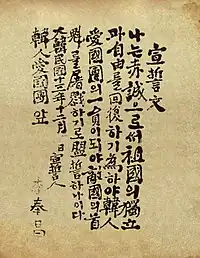

On December 13, Kim Ku and Lee went to the house of An Gong-geun (the younger brother of another famous activist An Jung-geun). Waiting for Lee at the house was the flag of the KPG and the two grenades.[1][2] Lee then swore this oath:[1][lower-alpha 12]

In order to restore independence and liberty to the fatherland, I do solemnly swear to become a member of the Korea Patriotic Organization and to slaughter (도륙) the leader of our enemy country.

They took a photograph to commemorate the occasion.[1]

On December 15, Kim gave Lee the two grenades and taught him how to use them.[lower-alpha 13] They spent the next few days preparing for the trip.[1] On December 17, the day finally came for Lee to depart.[1][2] They both arose at 8:30 am. After eating at a restaurant, they decided to take one last photo together. Lee, while posing for the photo, noticed that Kim had a dour expression on his face. He told Kim, "I'm about to set off on a journey for eternal bliss, so let the two of us take a picture with smiles on our faces". Moved, Kim smiled. The two shook hands, and Lee boarded a taxi bound for the docks.[1]

Return to Japan

At 3:00 pm, he boarded the ship Hikawa Maru bound for Kobe. He arrived at 8:00 pm on December 19 and stayed the night in an inn. He made his way through Osaka and arrived in Tokyo on December 22. On either December 28 or 29, Lee saw an article in the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun that said that the Emperor would be present at a public military parade on January 8 in Yoyogi Park.[1]

On January 6, after planning the attack, he wrote a quick memoir of his life, but suddenly felt that there was no point to it, and threw it in the trash bin of a restaurant he ate at. He then decided that he could hide the grenades in two paper candy boxes at the location in advance, but he did not end up doing this. Feeling that security was too tight in the area, he went all the way south to Kawasaki and spent the evening of the 7th in a brothel there.[1]

Sakuradamon incident

Legacy

After Korea achieved independence, Kim Gu interred Lee's remains at Hyochang Park, along with those of Yun Bong-gil and Baek Jeong-gi. Their grave site is known as the Graves of the Three Martyrs (삼의사묘; 三義士墓). A statue of Lee wielding a hand grenade is also located at the park.[4][5]

Lee was posthumously awarded the Order of Merit for National Foundation (Order of the President) in 1962.[6]

Personal life

Lee was popular and well-liked by many Japanese people. Kim later wrote of Lee departing from Shanghai:[1][lower-alpha 14]

The gentleman’s disposition flowed like a gentle spring breeze, but his spirit roared like a raging fire. Depending on who he spoke to, he could be kind and cheerful, but if once angered, take to stabbing them. He had limits on neither alcohol nor character... In the less than one year he lived at Hongkou, he made more than friends than you can count... When he left Shanghai, there were more than a few women who clung to his collar and shed tears, and among the friends who came to the wharf to wish him well was a Japanese police officer.

To Tokyo, Lee carried with him a glowing letter of reference from the chief of police at the Japanese consulate in Shanghai. The chief was one of many police and staff of the consulate that Lee had befriended. According to historian Son Sae-il, there were rumors that after Lee's attack, the chief was demoted and recalled to Japan, where he eventually committed suicide.[1]

Son alleges that, after Lee arrived in Japan, he was irresponsible with the money given to him. On December 20, 1931, Lee allegedly sent a telegram to Kim Ku, asking for 100 yen, as he had spent his travel expenses on alcohol. Running out of money, Lee pawned the watch Kim bought for him and went to an employment agency to find a quick job. On December 28, the employment agency found a spot for him at a sushi restaurant supply store. That same day, Kim sent Lee the 100 yen he had asked for. Ashamed, Lee wrote Kim a letter that read "I spent money like a madman, and I've since racked up debts even for my meals. With this money, I'll have more than enough to pay back my debts".[1][lower-alpha 15]

See also

Notes

- ↑ 이진구; 李鎭球

- ↑ 이범태; 李範泰

- ↑ 금정청년회; 錦町靑年會

- ↑ Despite this, he ended up needing to pretend that he was Japanese for much of the rest of his life.[1]

- ↑ He called the group 가정부; 假政府; Kajŏngbu, which is the Korean reading of the Japanese name for the group. Most Koreans would instead call the group 임시정부; 臨時政府; Imshijŏngbu.[1]

- ↑ 『일본 천황을 죽이기는 아주 쉬운 일인데, 왜 독립운동자들이 이 일을 실행하지 아니합니까?』

- ↑ 『그렇게 쉬운 일이라면 왜 여태까지 못 죽였겠소』

- ↑ The Emperor had a villa near a beach in this area.[1]

- ↑ 『내가 연전에 동경 있을 때에 하루는 일본 천황이 하야마[葉山 : 일본 가나가와(神奈川)현의 해수욕장으로 유명한 별장지. 천황의 별장이 있다]에 간다기에 구경하러 가서 보았는데, 천황이 바로 내 앞으로 지나가는 것을 보고 〈이때에 내게 총이나 폭탄이 있으면 어찌할까〉 하는 생각이 얼른 들었습니다』

- ↑ 『제 나이 서른한 살입니다. 앞으로 다시 서른한 살을 더 산다 하여도 과거 반생 동안 방랑생활에서 맛본 것에 비한다면 늙은 생활이 무슨 재미가 있겠습니까. 인생의 목적이 쾌락이라면 31년 동안 육신으로는 인생쾌락은 대강 맛보았으니, 이제는 영원한 쾌락을 도모하기 위해 우리 독립사업에 헌신할 목적으로 상해로 왔습니다』

- ↑ Korean age, his Western age was thirty at the time.

- ↑ 〈나는 赤誠으로써 조국의 독립과 자유를 회복하기 위하야 韓人愛國團의 일원이 되어 적국의 수괴를 도륙하기로 맹세하나이다.〉

- ↑ That evening, Lee emotionally thanked Kim, and commented that he was moved that Kim would trust him with a significant amount of money, especially given the ragged state of Kim's own clothes. Lee asked for a final farewell party in which he could publicly reaffirm his commitment to the independence movement, but Kim declined the request. The two stayed at the same inn for the night. The following day, Kim bought Lee a watch. Lee asked what he should do if he was arrested. Kim showed Lee the photo of the oath he had taken, and told him to withstand any torture and keep silent. In the worst case, Kim allowed Lee to share information about Kim only.[1]

- ↑ 〈이의사의 성행은 춘풍같이 화애하지만은 그 기개는 화염같이 강하다. 그러므로 對人談論에 극히 인자하고 호쾌하되 한 번 진노하면 비수로 사람 찌르기는 다반사였다. 술은 한량 없고 色은 제한이 없었다. 더구나 일본가곡은 못 하는 것이 없었다. 그러므로 홍구에 거주한 지 1년도 못 되어 그가 친하게 사귄 친구가 헤아릴 수가 없을 정도였다. 심지어 倭警察까지 그의 손아귀에서 현혹되기도 하고, ○○영사의 내정에는 무상출입이었다. 그가 상해를 떠날 때에 그의 옷깃을 쥐고 눈물지은 아녀자도 적지 아니하였지마는 부두까지 나와 가는 길이 평안하기를 기원하는 친우 중에는 왜경찰도 있었다.…〉

- ↑ 『돈을 미친 것처럼 다 써 버려서 밥값까지 빚이 져 있었는데, 돈을 받아 빚을 다 갚고도 남겠습니다』

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 손, 세일 (May 15, 2006). "孫世一의 비교 評傳 (50)" [Son Sae-il's Comparative Critical Biography (50)]. monthly.chosun.com (in Korean). Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "이봉창 (李奉昌)" [Lee Bong-chang]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ↑ "이봉창". terms.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ↑ 최, 용수 (June 17, 2021). "그냥 지나칠 수 없는 '효창공원 다섯 무궁화 이야기'". mediahub.seoul.go.kr (in Korean). Seoul Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Hyochang Park, Seoul". Cultural Heritage Administration. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ↑ "이봉창" (in Korean). Retrieved June 16, 2018.