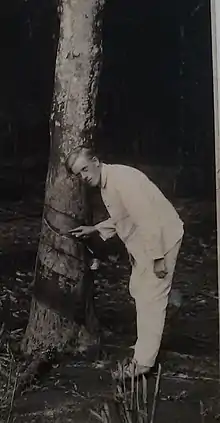

Leendert (Leen) Konijn (Zwammerdam, January 28, 1899 – Gorinchem, September 16, 1977) was a Dutch rubber planter (1920-1930) and entrepreneur in the cultivation of navel oranges and various citrus fruits at Lao Kawar, Mount Sinabung, North Sumatra, Dutch East Indies (1932-1942).

Biography

Leendert Konijn was born in Zwammerdam as the oldest child of twelve. His parents, Jan Konijn,[1] a bread baker and Janna Arnolda Kruithof were strict churchgoers and attended the Dutch Reformed Church. Konijn grew up in the small village of Tempel situated in the Bible belt in the western part of The Netherlands near the towns of Zwammerdam and Boskoop. As an adult Konijn would later leave the church. His strict father decided Konijn should study to become a school teacher. However, his true interest was for the cultivation of plants and fruits. After completing his studies an opportunity offered itself and Konijn applied for a job as a rubber planter with the Rotterdam Cultuur Maatschappij (RCM). The RCM were looking for young adventurous men, who were interested in working on a rubber plantation in the South Tapanuli Regency of North Sumatra, Dutch East Indies. In 1920, at the age of 21, Konijn boarded a freight ship[2] and left The Netherlands for Medan, Sumatra, Dutch East Indies.

Rubber plantations – Sumatra, Dutch East Indies - and marriage

The Tapanuli rubber plantation proved to be an excellent learning experience for Konijn and by September 1927 he had been promoted to the position of Acting Administrator (“administrator” is the then used terminology meaning “manager” of a plantation).[3] In May 1928, Konijn returned to The Netherlands on home leave. During his home leave he met his future wife, Anne-Marie Isaacs (Rotterdam, August 6, 1905-Gorinchem, May 20, 1979). They married at the Court House in Rotterdam on November 14, 1928. Konijn and Anne-Marie Konijn-Isaacs had four children, three daughters and one son. (Their son only survived his first year.) The Great Depression of August 1929 caused an enormous downturn in the rubber prices. This resulted in heavy financial losses for the RCM and consequently many planters lost their jobs. By the beginning of 1930 also Konijn received his notice. RCM transferred Konijn to an Assistant position at their smaller plantation in Badiri, Central Tapanuli Regency, North Sumatra, Dutch East Indies, but also this position ended by the end of 1930.

Cultivation of navel oranges – Citrus fruits – Lao Kawar, Mount Sinabung, North Sumatra, Dutch East Indies

Due to the ongoing economic crisis and lack of work in the rubber cultivation, Konijn's pioneering spirit focused on finding new ventures in Sumatra. He discovered that the fertile volcanic earth of Mount Sinabung was ideally suited for the cultivation of navel oranges and citrus fruits. To cultivate a navel orange equal to the quality of the navel oranges from California offered great possibilities since this had never been tried before in Sumatra. He was able to obtain 20 acres of land on Mount Sinabung near the lake “Lao Kawar”. This land belonged to the local Karo Radja and with assistance from the Dutch governor an agreement was reached. In March 1932 Konijn received official notification that he could start with setting up his “Lao Kawar Orange Cultivation”.[4] With the assistance of the Ministry of Agriculture of The Netherlands, Konijn was able to import 1800 orange pits from California. The cultivation of navel oranges was his main product. However, he also cultivated on a smaller scale lemons (Villafranca and Ponderosa) and grapefruits (Trimph, Manis besaar, Van Kuyk I and Duncan).[5] From 1932 to 1942 the family Konijn was able to sustain themselves and to carve out a modest living by the Lake Lao Kawar. Their first home was nothing more than a primitive hut built of flattened bamboo. With great courage and determination this young family managed to survive in the wilderness of the jungle, 25 kilometers away from any form of civilization. Local colonial newspapers published articles about the Family Konijn.[6][7][8]

Japanese invasion – World War II

The cultivation of the navel oranges was a great success. Only the Japanese invasion bringing the Second World War to Asia caused an early end to this promising enterprise. At the beginning of the year 1942 the Japanese accused Konijn of having a radio in his possession. For this reason, he was imprisoned in Brastagi. Later that same year Leendert Konijn was transferred to the Japanese concentration camp for men in Brastagi. At the time of liberation the name of Konijn appeared on the camp's death list. Because of his greatly weakened state he had been left to die in the hospital of the camp. Konijn survived and reunited with his family in August 1945. By the end of March 1942 (three months after Konijn had been taken away to prison) Anne Marie Konijn-Isaacs and her three daughters were also brought to the Japanese concentration camp for women in Brastagi. In June 1945, six weeks after the Japanese capitulation, this camp closed and the women and children were transferred to the camp “Aek Pamienke”.[9] Anne Marie Konijn-Isaacs and her three daughters also survived the camp and were liberated In August 1945.

Later years after World War II

From 1946 to 1948 Konijn worked for the Red Cross in Medan. At the beginning of 1946 Anne Marie Konijn-Isaacs and two of their daughters left for The Netherlands to recuperate. Their oldest daughter remained behind with her father in Medan, only to leave for The Netherlands as well a year later in 1947. In 1948, Konijn saw an opportunity to start a fertilizer wholesale business in Kabanjahe. Anne Marie Konijn-Isaacs and two of his daughters joined him there later that same year. Although the Indonesian War of Independence was already being fought and the climate had become hostile to Dutch citizens, the family chose to remain in the country despite the dangers.

Return to The Netherlands

In 1959, Konijn left Indonesia for The Netherlands, never to return.

See also

References

- ↑ Jan Konijn (Genealogieonline)

- ↑ S.S. Tabanan, sailed from Rotterdam on April 24, as reported in the newspapers De Tijd, Vol. 75, Nr. 22237, April 26, 1920 and De Maasbode, Vol. 52, Nr. 16872, April 25, 1920

- ↑ Correspondence by Leendert Konijn, Administrator of Rotterdam-Tapanoeli Cultuurmaatschappij and owner of the orange plantation at Lao Kawar, Kaban Djahe, Sumatra, Volume 1597 (1924) - Index of letters Archived 2016-08-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Newspaper article about Lao Kawar Orange Cultivation Archived 2017-04-18 at the Wayback Machine (Dutch)

- ↑ Advertisement in De Sumatra Post, 15 June 1940

- ↑ Delische Causeriën, De Indische Courant, 12 June 1933 (Dutch)

- ↑ Door Indiës Grootste Eiland (Travelling across Netherlands-Indies' largest island), Soerabajasch Handelsblad, 3 March 1936 (Dutch)

- ↑ Article in De Indische Courant, 29 April 1936 (Dutch)

- ↑ List of Japanese-run internment camps during World War II