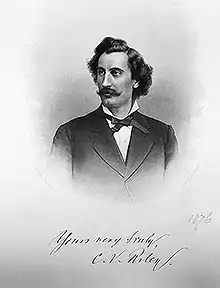

Leo Laliman was a winegrower and viticulturist from Bordeaux, France. He, along with fellow winegrower Gaston Bazille, is largely credited with the discovery that when European vines are grafted with suitable American rootstock, they become resistant to grape phylloxera.[1] This discovery was very relevant at the time, when France was suffering from a severe wine blight induced by the same phylloxera.

While Laliman was praised for his discovery, he was also a controversial figure at the time; for undocumented reasons, he was also branded by many as the introducer of the phylloxera, and, by extension, the crippling blight that came with it.

Background

The blight, termed the Great French Wine Blight, was a severe blight of the mid-19th century that resulted in the destruction of over 4 million vineyards and 40% of all the grape vines in France, and that subsequently laid waste to the wine industry there.[2]

This blight was brought on by a species of aphid that originated in North America and was carried across the Atlantic Ocean sometime in the late 1850s/early 1860s.[3][4] However, how the phyolloxera had survived the journey remained a point of much debate; Europeans had experimented with American vines for centuries without any pestilential problems. Eventually, it was decided that, following the invention of steamboats, the grape phylloxera were able to survive the shortened journey.

The first instance of the blight was recorded sometime in the early 1860s,[5] and France suffered the blight for a 15-year period, without any solution. Eventually, Jules-Emile Planchon and two colleagues made an important discovery; the discovery that sourced the aphid phylloxera to the blight itself — up until then, the source of the damage was unknown. In 1870, American entomologist Charles Valentine Riley confirmed Planchon's theory.[6] However, this discovery caused controversy; some met it with optimism, saying that now that the cause had been found, it would just be a matter of elimination. Others disagreed completely with the theory, saying that the grape phylloxera were merely a symptom, an effect, of the blight, rather than the source.

Solution

Shortly after Riley confirmed the theory proposed by Planchon, Laliman and Bazille, up until then two unknown winegrowers, proposed that the European vines, of the vinifera variety, may form a resistance to the destructive phylloxera if they were grafted with the American vine variety, which had formed a natural resistance.

The idea was tested, and proved successful.[7] Following this, France became divided again. Some, referred to as the "chemists", persisted with the use of pesticides and chemicals, while others, known as "Americanists", tried Laliman and Bazille's method.

Reward

The French government had, in desperation, offered a reward of over 320,000 Francs to anyone who could find a cure for the blight. Laliman, who was accredited over Bazille for the grafting solution, attempted to claim the prize money. The French government refused to award Laliman the money, claiming he had simply prevented the phylloxera's occurrence, rather than found a cure for it.[2] There may have been other reasons that the French government refused to give Laliman the prize money: the idea of grafting rootstock for agricultural advantage was not a completely novel concept, and he was also mistrusted among a large portion of the population.

Controversy

Laliman became quite a controversial figure following his and Bazille's discovery. While he was widely acclaimed and praised for his theory and its success, and was uncontroversially accredited for finding the solution to the problem, many others mistrusted his method, and were decidedly against grafting their rootstock with American vines. Others mistrusted him personally, and some claimed that he was, in fact, responsible for the introduction of the grape phylloxera. This public suspicion of Laliman may have been the true reason that the French government was against awarding Laliman the prize for "curing the blight".

References

- ↑ "Phylloxera: Why grafting to rootstocks is important" (PDF). Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- 1 2 "Great French Wine Blight". Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ↑ Phylloxera, from The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2004

- ↑ Campbell, Christy (6 September 2004). "Phylloxera: How Wine Was Saved for the World". Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ↑ Viticulture: An Introduction to Commercial Grape Growing for Wine Production. Published 2007. ISBN 0-9514703-1-0

- ↑ Smith, C. M. (2005) Plant Resistance to Arthropods: molecular and Conventional Approaches. Springer.

- ↑ Allan J. Tobin, Jennie Dusheck Asking about Life. Thomson Brooks/Cole, 2004. ISBN 0-534-40653-X, p. 628.