Lieutenant Leon Crane | |

|---|---|

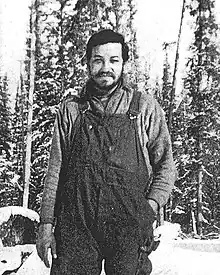

Crane one year after the crash, 1944 | |

| Born | 1919 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died | 2002 (aged 82–83) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Service/ | Army Air Corps |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Known for | Surviving 84 days in the Alaskan wilderness without many supplies or outside help |

Leon Crane (August 5, 1919 – March 26, 2002), a native of Philadelphia,[1] was an American Army Air Corps lieutenant who was stationed at Ladd Field[lower-alpha 1] in Alaska during World War II. During a routine test flight on December 21, 1943, the B-24 Liberator Crane was copiloting experienced engine failure, causing the plane to crash into a mountaintop overlooking the Charley River. Of the crew of five, Crane was the only survivor, having managed to bail out in time.[2][3] Crane then was able to survive for 84 days in the Alaskan wilderness with only some matches, a Boy Scout knife and his parachute, before reaching a nearby mining camp.[4][5][6][7]

B-24 incident and survival

Plane crash

In the early morning of December 21, 1943, Crane was co-piloting a B-24 from Ladd field on a routine test flight. With him was pilot Second Lieutenant Harold "Hos" Hoskins, flight engineer Richard Pompeo, radio operator Ralph Wenz (for whom Ralph Wenz Field is named), as well as James E. Seibert.[2][3] Their craft took off at 9:45 am, and radioed its position at 10:03 and 10:30. At 11:00, it radioed that the crew was searching for a hole in the clouds to ascend through. A little before noon, Hos noticed a hole that looked large enough to climb through and began a circling climb. However, Hos had miscalculated the size of the cloud opening, and the B-24 soon became engulfed by the clouds, putting them in IFR conditions (visibility less than 3 miles (4.8 km)). Suddenly, the No. 1 engine failed, and the vacuum selector valve froze. Within seconds, the B-24 entered a spin from 20,000 feet (6,100 m) towards the ground.[2][8] Wenz had enough time to radio that their engine had failed and that they were in a spin, but not enough time to radio their location. While Hos and Crane were able to break out of the spin, it sent them straight into a 300-mile-per-hour (480 km/h) nosedive from which they could not recover. Crane had just enough time to bail out before the plane dived into the side of a mountain near the Charley River in a ball of flame.[7][9]

Survival

As Crane landed hip-deep in snow he repeatedly called "Ho!" loudly but did not get a response. Having no food or idea of his whereabouts, he began descending to the river below. Crane had only three survival tools—a Boy Scout knife, two packs of matches, and his parachute.[2]

For the next nine days Crane camped in a makeshift campsite, maintaining a fire with the little matches he had, sleeping in his parachute and attempting to kill squirrels for food but with no luck. After nine days of living off nothing but water from under the frozen river, Crane began to trek along the river north, now believing a rescue party to be unlikely.[2][3]

After a day of struggling through the snow, Crane stumbled across a small, snow-covered cabin, just large enough to hold a bed, table, and small stove. The cabin contained canned food, sugar, powdered milk, a rifle, tents, mittens and other vital supplies. The cabin had been owned and built by trapper Phil Berail.[2] Crane would later learn that hunters and trappers built a series of cabins in this area as outposts for their work, some stocked with supplies. The next day, Crane traveled a little further down the river, hoping to find a village, but with no luck. For the next week, Crane stayed in the cabin and focused on fighting his frostbite that had begun to develop and regaining his strength.[3] One night, Crane discovered a map of Alaska in the cabin, and saw that the nearest settlement was the mining camp of Woodchopper, Alaska, where Phil Berail was from. The next day, he decided to venture out further from the cabin down the river, where he found a second and third cabin, both abandoned and rotting, before returning to Phil's cabin, where he stayed for the next few weeks.[2][3][6]

Before leaving Berail's cabin for good, Crane made a simple sled out of wood planks for him to carry supplies to sustain him on his journey to Woodchopper. On February 12 he began his slow trek down the river pulling his sled, which was much harder than he had imagined. Very quickly, however, his foot broke through the ice, freezing immediately around his mukluk, which he had found in the cabin. Crane then had to spend the night thawing it on a fire, hoping to not re-develop frostbite.[2][3] Several days later, disaster struck again. Crane fell through the ice and found him self almost completely submerged in freezing water. Knowing he had only minutes to live, Crane scrambled to shore, quickly stripped his clothes off and started a fire, barely avoiding death. Setting out again the next day, he came across another small cabin with food, where he rested for three days.[2] Several days later, as Crane was traveling across the ice again, his sled broke the ice under it and all his supplies fell into the river. Crane only managed to salvage a few essentials such as food and the rifle.[3] After 8 days, he reached the Yukon River.[2][6]

The next day, Crane came across a sled dog trail that led straight to another cabin, this time one that was inhabited by a native man named Albert Ames and his family. Crane explained his incredible story to the astonished family of walking 120 miles (190 km) down the Charley River in sub-zero conditions. Ames told him that they were 30 miles (48 km) from Woodchopper, and offered to give Crane a ride in his dog sled to the town.[2][3] At Woodchopper, contact was made to Ladd Field in which the operator was told that Crane was, in fact, alive and well.[5] Crane was even able to meet Phil Berail while at Woodchopper, who was glad his cabin was of use to Crane. He said that it was the custom of Alaskan trappers to keep their cabins well-stocked in case a traveling stranger is in need of refuge.[7]

After returning to Ladd Field, a surgeon evaluated Crane to be in good health, even having gained a little weight.[2] After calling Crane's parents to assure them that their son was alive, Crane joined a rescue team to locate the site of the crash and search for the other missing crewmen. At the crash site, the remains of Lieutenant Seibert and Sergeant Wenz were found, but no trace was found of Hoskins or Pompeo until 2006, when a research team at the site of the crash discovered metal buckles determined to be from Hoskin's parachute, with Hoskin's remains nearby. Hoskin was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors on September 7, 2007.[3][7][9][10]

Later life

Not much is known about Crane after he retired from the Army Air Force after World War II. After returning home to Philadelphia, Crane became an aeronautical engineer, helping to design some of the first helicopters.[7] Later, he started a construction business with three of his six children.[7][9] Three years after Crane’s death, two of his children went on an eight-day journey by plane and river raft along the path their father had taken, finding both the Berail and Ames cabin, both now just collapsed piles of logs.[7]

81 Days Below Zero

A book about Leon Crane's survival story was written by Washington Post journalist Brian Murphy and his wife, Toula Vlahou, called 81 Days Below Zero: The Incredible Survival Story of a World War II Pilot in Alaska’s Frozen Wilderness.[lower-alpha 2] First published June 2, 2015, the book depicts the firsthand account of Crane during his time in the Arctic, based on firsthand accounts from Crane from a radio interview, as well as military records. Although the overall structure and plot of the story was based on these records, Murphy had to fill in missing gaps using dialogue and passages that are "extrapolations from his own words as well as insights into his personality from his family and acquaintances." The book was published by Da Capo Press.[3][11]

Notes

- ↑ Ladd Field is now known as Fort Wainwright; however, the actual landing strip at the base is still called Ladd Field.

- ↑ While Crane spent 84 days in the Arctic, Murphy does not include the 3 days he spent at the Ames’ cabin or in Woodchopper, Alaska.

References

- ↑ "United States, Social Security Numerical Identification Files (NUMIDENT), 1936-2007", database, FamilySearch(https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6KMQ-VY1D : 10 February 2023), Leon Crane, .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Chandonnet, Fern (September 15, 2007). Alaska at War, 1941–1945: The Forgotten War Remembered. University of Alaska Press. ISBN 978-1-60223-135-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Murphy, Brian (June 2, 2015). 81 Days Below Zero: The Incredible Survival Story of a World War II Pilot in Alaska's Frozen Wilderness. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-306-82329-9.

- ↑ "FALLEN U.S. FLIER 84 DAYS IN ARCTIC; Lieutenant Brings First Word of His Bomber, Missing With Five Men Since Dec. 21". The New York Times. March 17, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- 1 2 "Lt. Leon Crane (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Fairbanks, Mailing Address: 101 Dunkel St Suite 110; Us, AK 99701 Phone: 907-459-3730 Contact. "A WW II Survival story from the Charley River – Yukon – Charley Rivers National Preserve (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Slomski, Anita (2007). "The Long Trip Home" (PDF). National Parks.

- ↑ "Valor: Alone in the Arctic". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "How one man's obsession led to the discovery of a lost WWII pilot". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Pilot's survivors thankful for determined historian". Air Force. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ↑ "81 Days Below Zero: The Incredible Survival Story of a …". Goodreads. Retrieved March 10, 2023.