| Levedi | |

|---|---|

| first voivode of the Hungarians | |

Modern portrait by Tamás Tulipán | |

| Reign | early 9th century (?) |

| Successor | Álmos (?) |

| Spouse | Khazar lady |

| Issue | none |

Levedi, or Lebed,[1][2][3] Levedias, Lebedias, and Lebedi[4] (Greek: Λεuεδίας)[5] was a Hungarian chieftain, the first known leader of the Hungarians.[6][7][8][9]

According to Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus' De administrando imperio, because of the alliance and the courage shown by the Hungarian people in all the wars they fought with the Khazars, Levedi, the "first voivode" ("protos voevodos", Greek: πρώτος βοέβοδος) of the Hungarians, who was also famous for his valor, was given a Khazar noble lady in marriage "so that she might have children by him".[10] However, as it turned out, Levedi did not produce offspring with this lady.

Later, after the Khazars defeated the Perchengs and forced them to resettle in the land of the Hungarians, whom they defeated and split in two, the Khazars picked Levedi, the "first among the Hungarians"[10] and sought to make him the prince of the Hungarian tribes so that he "may be obedient to the [Khazars'] word and [their] command". Thus, according to Constantine, the Khazar khagan initiated the centralization of the command of the Hungarian tribes in order to strengthen his own suzerainty over them.[11][12] Levedi, however, refused, because he wasn't "strong enough for this rule". Instead, Constantine claims, Levedi proposed another Hungarian voivode, Álmos or his son Árpád as prince of the Hungarians.

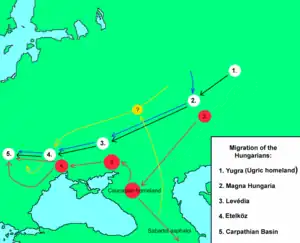

The Magyar settlement between the Volga river and the Urals the mountains were named Lebedia, soon to become Levedia, after Levedi.[13][1][14][15]

Name and title

The only source of Levedi's life is the De administrando imperio,[16] a book written by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus around 950.[17] According to one theory, the name is derived from the common Slavic word "Lebedi", swan.[18] According to historian Omeljan Pritsak, Levedi's name―which was actually a title―derived from the Turkic expression "alp edi", or "brave lord".[16][lower-alpha 1] The Hungarian historian Gyula Kristó, who refuses Pritsak's theory, says that Levedi's name is connected to the Hungarian verb "lesz" ("be").[16] Other scholars agree that the origin of the name is probably Finno-Ugric.[24][25] It derives from "the participle of the old lesz ('will be') verb lës (meaning levő - 'being') with the diminutive suffix -di."[25] A similar proper name (Lewedi) was recorded in a Hungarian charter, issued in 1138.[26]

It has also been put forward that the land, Lebedi, did not derive its name from the chieftain, but the other way around. Thus, the voivode had gotten his name from the land.[18] However, Kristó says that this would be in contrast with the source and the Hungarian practice of giving names.[18]

Levedi bore the title "voivode", which is of Slavic origin.[27] When using that title, Porphyrogenitus always referred to the heads of the seven Hungarian tribes.[28] Historian Dezső Paizs says that Levedi was the head of specifically the Megyer tribe (one of the seven ancestral Hungarian tribes), but his theory has not been widely accepted.[29]

In De administrando imperio

In the De administrando imperio Levedi is said to be one of the voivode of one of the seven clans of Hungarians, who lived together with the Khazars for a period of time. They are said to have fought in alliance with the Khazars in all their wars. Then, because of the courage of the Hungarians and their alliance, the chagan-prince (Khazar khan) gave a noble Khazar lady (i.e. not a member of the Khan's family) in marriage to their first voivode Levedi. The Hungarians, who had lived together with the Khazars, as a separate entity, and fought valiantly with them, had shown the Khagan their people's illustriousness and courage, and he gave the first among them a princess to marry. However, Levedi had no children by her. The Percheng, said by Constantine to have been previously called Kangar (Κάγγαρ), after being defeated and displaced by the Khazars into the Hungarians' land, waged war against the Hungarians and, Constantine continues, the Hungarians were defeated and forced to leave their homeland (in fact, it was the Magyars' intervention in a conflict between the First Bulgarian Empire and the Byzantine Empire that caused a joint counter-invasion by the Bulgars and Pechenegs[30]). He then says that the Hungarians (who Constantine erroneously calls Turks throughout) split into two parts: one went to Persia (Περσία) and the other, together with their chieftain Levedi, settled westward. The Khazar khan sent a message to the Hungarians. He required that Levedi be sent to him. Levedi accepted and went to the khan. He asked the chagan why he sent for him, and the latter replied: "We have invited you upon this account, in order that, since you are noble and wise and valorous and first among the [Hungarians], we may appoint you prince of your nation, and you may be obedient to our word and our command." But he, in reply, answered the chagan: "Your regard and purpose for me I highly esteem and express to you suitable thanks, but since I am not strong enough for this rule, I cannot obey you; on the other hand, however, there is a voivode other than me, called [Álmos], and he has a son called [Árpád]; let one of these, rather, either that [Álmos] or his son [Árpád], be made prince, and be obedient to your word." The chagan was satisfied by the proposal, and sent him back with some of his men. After discussing the matter with his people, they together chose Árpád as their prince. They chose him because he was of superior parts, and greatly admired for his wisdom. They raised him on a shield and made him their prince. Years later, the Perchenegs fell on the Hungarians, and drove them out with their prince Árpád. In turn, the Hungarians drove out the inhabitants of great Moravia and settled in their land. Up to the time when Constantine is writing, he says, they weren't attacked again by their enemies the Perchenegs anymore.[10]

Constantine notes that the Hungarians raised Árpád on the shield in the manner of the Khazars. Indeed, the historical social structure of the Hungarians was of Turkic origin.[22] The Hungarian language is abundant in words of Turkic origin, and the Hungarians do have some Turkic genetic and cultural influence. However, they are not a Turkic people.[31] On the other hand, as expressed by Constantine, they lived among the Khazars, fighting in all their wars, and the first among them, Levedi, was given a Khazar noble lady in marriage.

Historic interpretations

Regarding his person and his role, many theories have emerged in the Hungarian historiography of the last two hundred years. Antal Bartha considered Levedi a fictional, mythical figure.[32] Tamás Hölbling claimed that Constantine invented his person (a "phantom-figure") from the place name of Levedia.[5] István Katona, Károly Szabó, Gyula Pauler, Ignác Acsády, Bálint Hóman and György Györffy identified him with Előd, who appears as the father of Álmos in Simon of Kéza's Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum.[33] Géza Fehér argued, the later Hungarian chronicles Levedi's actions in connection with the conquest of the Carpathian Basin were attributed to Álmos, but his name was preserved in the form "Előd".[34] In contrast, linguist Katalin Fehértói emphasized phonetic incompatibility between the names Levedi and Előd.[32] Györffy claimed that Levedi's original name form was "Elwedi", which was then modified through Slavic adoption.[34] Based on linguistic consideration, Sándor László Tóth raised the possibility of identity between Levedi and Liüntika, Árpád's son, however Constantine's work contradicts this possibility where both persons are included.[32]

Based on his name, the turkologist Gyula Németh claimed that Levedi originated from an aristocratic family which had roots from Magna Hungaria.[35] Gyula Kristó considered that Levedi is the first Hungarian prince ("fejedelem", i.e. supreme leader) known by name.[33] Makk argued Levedi functioned as the paramount chieftain among the voivodes of the Hungarian tribes.[36] Hóman claimed that Levedi (Előd) held the title of kende, while Géza Fehér considered he served as gyula, attributing the system of dual-monarchy to the political situation in Levédia then Etelköz by both historians. Regarding Levedi's resignation from power, Györffy did not consider it plausible that Levedi would voluntarily raise the head of another tribe (Álmos) to power.[37] According to Iván Uhrman, the emperor misunderstood the communication and Levedi only emphasized that Álmos was more suitable for the position due to his fertility.[38] Györffy claimed that Kurszán was the son of Levedi, and both of them held the title kende.[39] Kristó said that Levedi functioned as "first voivode" initially, then he was promoted to the status of kende as a Khazar-proxy ruler (the historian later modified this standpoint).[40] Sándor László Tóth claimed that Levedi plausibly held the dignity gyula and he was responsible for the tribal federation's foreign affairs.[41]

According to István Zimonyi, the 38th chapter, which narrates Levedi's story, can be outlined according to two chronological concepts: a real (20–70 year interval) and a mythical (150–230 interval).[42] Belonging to the latter, József Deér considered that Levedi lived in the second half of the 8th century. According to him, Constantine placed Árpád as his contemporary because the former's descendants, who informed the emperor, already consciously wanted to magnify the role of their ancestor in the organization of the state. Thus the Hungarian informants delibaretly misled the emperor and his Byzantine court.[37] Dezső Dümmerth even claimed that Levedi lived in the 7th century. He argued that Constantine obtained the information from a Hungarian legation led by Bulcsú and Termacsu (Árpád's great-grandson) to Constantinople around 948. Jenő Szűcs also attributed Levedi's lifespan to the turn of the 7th and 8th centuries.[43] György Szabados highlighted the irreconcilable contrast between the two passages of text: at first, Levedi appears as a voivode, first among equals, in an aristocratic independent proto-state, which is an equal ally of the Khazar Empire, while the second chapter refers to him as the appointed archon of a monarchical organization destined for submission, who finally did not take his office.[44] Realizing this contradiction, inguist Jenő Ungváry separated Levedi, the "first voivode" (i.e. the earliest) of the Hungarians from that namesake chieftain, who was a contemporary of Álmos and Árpád. According to Ungváry, Levedi (II) led the majority of Hungarians into Etelköz in the mid-9th century, while Álmos headed the Savard Hungarians (a group who moved across the Caucasus into Persian territory). Taking into account the wording of the original Greek-language source, Ferenc Makk argued effectively against the theory.[36] Szabados argued the Hungarians was not subjugated by the Khazars, but they were allies for only three years (several historians extended this period to centuries). Following Deér and Dümmerth, Szabados argued Levedi could have lived anytime from the 630s to the 830s.[45] There are also arguments (e.g. Carlile Aylmer Macartney, Henri Grégoire and Sándor László Tóth) that the De administrando imperio, due to a careless compilation, tells the same story twice, only relying on a different source of information.[46]

Representing the "real chronological concept", Gyula Kristó handled the 38th chapter as a single and coherent story. According to him, Levedi was born around 800. The Hungarians moved from Bashkiria to Levedia around 830. Around that year, Levedi was given a Khazar lady to marriage and was appointed head (kende) of the Hungarians by the Khazars. Under his leadership, the Hungarians lived in Levedia until around 850, when they were defeated by the Kangars (or Pechenegs). Shortly after they moved to Etelköz. Levedi was summoned before the khagan in order to appoint him a prince but he refused this in favor of Álmos or Árpád. He was succeeded by Álmos in the 850s.[47] Ferenc Makk and Loránd Benkő shared this viewpoint. According to Gábor Vékony, the Hungarians' status under Khazar rule and their living space in Levedia really only lasted three years, occurred in the 840s. They fled to Etelköz after a Pecheneg attack up to 850. Gyula Pauler then Gyula Németh considered Levedi ruled over the Hungarians for 50–60 years and his resignation took place only around 889, shortly before the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin (895). Károly Czeglédy claimed Levedi allied with the Khazars from 886 to 889 and they fought each other against the Pechenegs. After their defeat, the Hungarians fled to Etelköz. Levedi wanted to avoid the fate of sacrifice after the military failure, thus resigned from his position in favor of Álmos. György Györffy considered that Levedi, as kende, headed the Hungarian tribes in the period between 870 and 893. Thereafter, he was succeeded by Kurszán – Levedi's son, according to Györffy – in this position. János Harmatta put Levedi's leadership into the 880s.[48]

Balázs Sudár analyzed the political context of Levedi's marriage with the Khazar lady. He emphasized that – despite the unfounded claims of several historians – Constantine's work do not mention that the aforementioned lady was relative of the khagan nor the Khazar royal dynasty. So Levedi was clearly at a lower level in terms of social status than the khagan, and cannot be considered the head of all Hungarians.[49] The marriage was clearly initiated by the Khazars. Sándor László Tóth argued the khagan wanted to ensure Levedi's loyalty and the formation of a pro-Khazar Hungarian ruling dynasty with this step.[50] However, the marriage remained childless. Citing steppe nomadic parallels, Sudár considered that perhaps Levedi had no intention of founding a "joint" dynasty with the Khazars, so he could have consciously kept away from having children from his wife.[51] Regarding the second part of the narration, Tóth emphasized that Levedi appears as a subordinate party when the Khazars call him to negotiate to Atil, but his importance is reflected by the fact that the khagan himself received him, instead of the bek or the isad. Tóth considered the khagan sought to appoint a prince who depended on him and obeyed him as the head of the Hungarian tribes.[52]

Until the early 20th century, majority of historians (e.g. Paulus Stephanus Cassel, Károly Szabó, Henrik Marczali and Gyula Pauler) argued that Constantine VII and his court were informed about the Hungarians by Khazar (and possibly Pecheneg) envoys, thus its narration is not reliable regarding Levedi's state of dependence to the Khazars.[53] István Kapitánffy considered that information from roughly contemporary Byzantine envoys was also incorporated into the material about the Hungarians, but Kristó refused this theory.[46] As a result of the research of linguists (e.g. Zoltán Gombocz, Jenő Darkó, Géza Fehér), the 20th-century Hungarian historiography, instead of the previous decades, extended the westward migration of Hungarians to centuries starting from the Volga river. They also claimed that Constantine's information about the Hungarians was originated from the narrations of envoys Bulcsú and Termacsu around 948, overshadowing the text showing exaggerated Khazar influence. In their 2022 monograph, Ádám Bollók and János B. Szabó returned to the 19th-century mainstream. Accordingly, the Hungarians arrived to Levedia only around the 840s or 850s. "Levedia" laid northeast or northwest of the Khazar Empire. The khagan made an attempt to integrate the Hungarians into their federal system. Levedi was accepted as their client and was integrated into their political structure due to his marriage with the Khazar lady. As a result of an invasion, the Hungarians lived in the territory of the Khazars for three years. Under the pressure of the Pechenegs, the Hungarians moved into Etelköz in the 860s or 870s. According to the two historians, Levedi proposed Álmos or Árpád in the court of the khagan, because their family had greater internal legitimacy, and Álmos was elected by the Hungarians themselves.[54]

References

- 1 2 Northern Magill, Frank (1998). Dictionary of World Biography Volume 2. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 86. ISBN 9781579580414.

- ↑ Lukinich, Imre (1968). A History of Hungary in Biographical Sketches. Books for Libraries Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 9780836906356.

- ↑ Bartha, Antal (1976). Hungarian Society in the 9th and 10th Centuries Volume 85. Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 48. ISBN 9789630503082.

- ↑ Nagy, Sándor (1973). The Forgotten Cradle of the Hungarian Culture. Patria Pub. p. 136. ISBN 9780919368040.

- 1 2 Tóth 2015, p. 84.

- ↑ Pop, Ioan Aurel; Csorvási, Veronica (1996). Romanians and Hungarians from the 9th to the 14th Century The Genesis of the Transylvanian Medieval State. Centrul de Studii Transilvane; Fundația Culturală Român. pp. 62, 227. ISBN 9789735770372.

- ↑ Mekhon Ben-Tsevî shel yad Yitsh.ak. Ben-Tsevî (Yerûšālayim) (2007). The World of the Khazars New Perspectives. Brill. p. 274. ISBN 9789004160422.

It is related that sometime earlier the Khazar ruler wanted to promote Levedi, a Hungarian chieftain to become the first arkhon among the Hungarians.

- ↑ Frank Northern Magill (2007). Great Events from History: Ancient and Medieval Series: 951-1500. Salem Press. p. 1212.

[...] the temporary settlements of Levedia and Etelköz. The former is called after Levedi, the first Hungarian chieftain to be mentioned by name.

- ↑ Gyula Moravcsik, Constantine Porphyrogenitus de Administrando Imperio, Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, 1967, p 171

- 1 2 3 Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 38), p. 171.

- ↑ Kristó 1996, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, p. 33.

- ↑ "Grozer Traditional Recurve Bows Hungary".

- ↑ Klaniczay, Gábor (2002). Holy Rulers and Blessed Princesses Dynastic Cults in Medieval Central Europe. Reaktion Books. p. 435. ISBN 9780521420181.

- ↑ Klaniczay, Gábor (2002). Piroska and the Pantokrator Dynastic Memory, Healing and Salvation in Komnenian Constantinople. Central European University Press. p. 146. ISBN 9789633862971.

- 1 2 3 Kristó 1996, p. 112.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Kristó 1996, p. 107.

- ↑ Gy Ránki, György Ránki, ed. (1984). Hungarian History--world History. Akadémiai K VIII. p. 10. ISBN 9789630539975.

- ↑ Pop, Ioan Aurel; Csorvási, Veronica (1996). Romanians and Hungarians from the 9th to the 14th Century The Genesis of the Transylvanian Medieval State. Fundația Culturală Română; Centrul de Studii Transilvane. p. 62. ISBN 9789735770372.

The majority of the Hungarian tribe names were of Turkic origin and signified, in many cases, a certain rank.

- 1 2 Marcantonio, Angela; Nummenaho, Pirjo; Salvagni, Michela (2001). "The "Ugric-Turkic Battle": A Critical Review" (PDF). Linguistica Uralica. 2. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- 1 2 Köpeczi, Béla; Makkai, László; Mócsy, András; Kiralý, Béla K.; Kovrig, Bennett; Szász, Zoltán; Barta, Gábor (2001). Transylvania in the medieval Hungarian kingdom (896-1526) (Volume 1 of History of Transylvania ed.). New York: Social Science Monographs, University of Michigan, Columbia University Press, East European Monographs. pp. 415–416. ISBN 0880334797.

- ↑ Jenkins, Romilly James Heald (1967). De Administrando Imperio by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus. Corpus fontium historiae Byzantinae (New, revised ed.). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-88402-021-9. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ↑ Alfried Wieczorek, Hans-Martin Hinz [in German], ed. (2000). Europe's Centre Around AD 1000. Theiss. p. 370. ISBN 9783806215496.

- 1 2 Kósa, László [in Hungarian] (1999). A Companion to Hungarian Studies. Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 43. ISBN 9789630576772.

- ↑ Kristó 1996, p. 370.

- ↑ Kristó 1996, p. 115.

- ↑ Kristó 1996, p. 114.

- ↑ Kristó 1996, p. 9.

- ↑ Spinei 2003, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ A MAGYAROK TÜRK MEGNEVEZÉSE BÍBORBANSZÜLETETT KONSTANTINOS DE ADMINISTRANDOIMPERIO CÍMÛ MUNKÁJÁBAN - Takács Zoltán Bálint, SAVARIAA VAS MEGYEI MÚZEUMOK ÉRTESÍTÕJE28 SZOMBATHELY, 2004, pp. 317–333

- 1 2 3 Makk 1999, pp. 189–190.

- 1 2 Szabados 2011, pp. 63–64.

- 1 2 Tóth 2015, p. 85.

- ↑ Tóth 2015, p. 87.

- 1 2 Makk 1999, pp. 191–195.

- 1 2 Szabados 2011, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Szabados 2011, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Tóth 2015, p. 93.

- ↑ Kristó 1996, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Tóth 2015, p. 94.

- ↑ Tóth 2015, p. 96.

- ↑ Tóth 2015, p. 97.

- ↑ Szabados 2011, p. 95.

- ↑ Szabados 2011, p. 113.

- 1 2 Tóth 2015, p. 77.

- ↑ Kristó 1996, pp. 159–167.

- ↑ Tóth 2015, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Sudár 2018, p. 500.

- ↑ Tóth 2015, p. 147.

- ↑ Sudár 2018, p. 502.

- ↑ Tóth 2015, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Bollók & B. Szabó 2022, pp. 114–117.

- ↑ Bollók & B. Szabó 2022, pp. 201–209, 212–214.

Notes

- ↑ Regardless of its origin, scholars have warned against taking a name's etymology as automatically showing the bearer's ethnicity. The Hungarians cohabited for centuries with the Turkic people, who gave them a significant genetic, linguistic and cultural contribution. About 10% of Hungarian word roots is Turkic; pastoral terms are most Turkic in origin, and agricultural terms are 50% r-Turkic. Many Hungarian names, and also animal and plant names,[19] are of Turkic origin, and tribal names were no exception. Indeed, the majority of tribe names were of Turkic origin.[20] Through the 18th and into the 19th centuries it was debated whether to classify the Hungarian language as Turkic.[21] The historical social structure of the Hungarians itself was of Turkic origin.[22] Likewise, Slavic language also had an influence on Hungarian.[21] In spite of all this, the Magyars are not a Turkic nor a Slavic people.[23]

Sources

Primary sources

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation by Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

Secondary sources

- Berend, Nora; Urbańczyk, Przemysław; Wiszewski, Przemysław (2013). Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c. 900-c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78156-5.

- Bollók, Ádám; B. Szabó, János (2022). A császár és Árpád népe [The Emperor and the People of Árpád] (in Hungarian). BTK Magyar Őstörténeti Kutatócsoport, Források és tanulmányok 8., ELKH Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont. ISBN 978-963-416-304-6.

- Cartledge, Bryan (2011). The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-84904-112-6.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Kristó, Gyula (1996). Hungarian History in the Ninth Century. Szegedi Középkorász Muhely. ISBN 963-482-113-8.

- Makk, Ferenc (1999). "Levedi, a fővajda [Levedi, the Chief Voivode]". In Klaniczay, Gábor; Nagy, Balázs (eds.). A középkor szeretete. Történeti tanulmányok Sz. Jónás Ilona tiszteletére (in Hungarian). ELTE BTK Közép- és Koraújkori Egyetemes Történeti Tanszék. pp. 189–196. ISBN 963-463-348-X.

- Róna-Tas, András (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History (Translated by Nicholas Bodoczky). CEU Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-48-1.

- Spinei, Victor (2003). The Great Migrations in the East and South East of Europe from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century (Translated by Dana Badulescu). ISBN 973-85894-5-2.

- Sudár, Balázs (2018). "A kazár menyasszony [The Khazar Bride]". In Kincses, Katalin Mária (ed.). Hadi és más nevezetes történetek. Tanulmányok Veszprémy László tiszteletére (in Hungarian). HM Hadtörténeti Intézet és Múzeum. pp. 500–505. ISBN 978-963-7097-87-4.

- Szabados, György (2011). Magyar államalapítások a IX-X. században [Foundations of the Hungarian States in the 9th–10th Centuries] (in Hungarian). Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. ISBN 978-963-08-2083-7.

- Tóth, Sándor László (2015). A magyar törzsszövetség politikai életrajza [A Political Biography of the Hungarian Tribal Federation] (in Hungarian). Belvedere Meridionale. ISBN 978-615-5372-39-1.