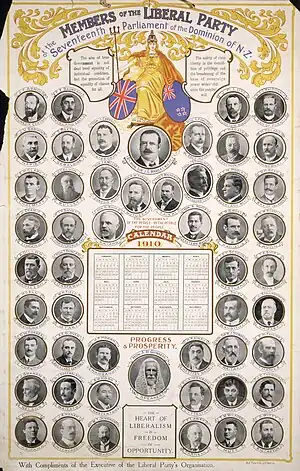

Liberal Party of New Zealand | |

|---|---|

| Founder | John Ballance |

| Founded | 1891 |

| Dissolved | 1928 |

| Succeeded by | United Party |

| Ideology | Liberalism Populism Agrarianism |

| Political position | Centre to centre-left |

| Colours | Yellow |

| Slogan | "We legislate no class, but for all classes." |

The New Zealand Liberal Party (Māori: Pāti Rīpera)[1] was the first organised political party in New Zealand. It governed from 1891 until 1912. The Liberal strategy was to create a large class of small land-owning farmers who supported Liberal ideals, by buying large tracts of Māori land and selling it to small farmers on credit. The Liberal Government also established the basis of the later welfare state, with old age pensions, developed a system for settling industrial disputes, which was accepted by both employers and trade unions. In 1893 it extended voting rights to women, making New Zealand the first country in the world to enact universal adult suffrage.

New Zealand gained international attention for the Liberal reforms, especially how the state regulated labour relations.[2] It was innovating in the areas of maximum hour regulations and compulsory arbitration procedures. Under the Liberal administration the country also became the first to implement a minimum wage and to give women the right to vote.[3] The goal was to encourage unions but discourage strikes and class conflict.[4] The impact was especially strong on the reform movement in the United States.[5]

It is widely argued that the New Zealand Liberal Party in 1891 lacked a clearcut ideology to guide them. Instead they approached the nation's problems pragmatically, keeping in mind the constraints imposed by democratic public opinion. To deal with the issue of land distribution, they worked out innovative solutions to access, tenure, and a graduated tax on unimproved values.[6]

Out of office after 1912, the Liberals gradually found themselves pressed between the conservative Reform Party and the growing Labour Party. The Liberals fragmented in the 1920s, and the remnant of the Liberal Party—later known as the United Party—eventually merged with Reform in 1936 to establish the modern National Party.

Liberal Government

Prior to the establishment of the Liberal Party, MPs were all independent, although often grouped themselves into loose factions. Some of these factions were occasionally referred to as "parties", but were vague and ill-defined. In the history of Parliament, factions were formed around a number of different views – at one time, centralism and provincialism were the basis of factions, while at another time, factions were based on geographical region. Towards the 1880s, however, factions had gradually become stabilised along lines of liberalism and conservatism, although the line between the two was by no means certain.[7][8]

The key figure in the establishment of the Liberal Party was John Ballance. Ballance, an MP, had served in a number of liberal-orientated governments, and had held office in posts such as Treasurer, Minister of Defence, and Minister of Native Affairs. He had a well-established reputation as a liberal, and was known for supporting land reform, women's suffrage, and Māori rights.[9]

During the last term in power of Harry Atkinson, a conservative, Ballance began to organise the liberal-aligned opposition into a more united movement, and was officially named Leader of the Opposition in July 1889. In the 1890 elections, Ballance led his liberal faction to victory, and early in the new year, became Premier.[10] Ballance and his allies, recognising the benefit that they had gained from their unity, set about building a permanent organisation. The Liberal Party, with common policies and a well-defined leadership, was proclaimed. A national party organisation (called the Liberal Federation) was established, with supporters of the new party encouraged to become members and help organise party activities – this was a new development in New Zealand, as previously, parliamentary factions existed only as loose groupings of politicians, not as structured party organizations.[11]

Early days

The Liberal Party drew its support from two basic sources – the cities, and small farmers. In the cities, the Liberals were supported particularly strongly by workers and labourers, but also by the more socially progressive members of the middle class. In the countryside, the Liberals won support from those farmers who lacked the ability to compete with the large runholders, who monopolised most of the available land. Both groups saw themselves as being mistreated and oppressed by what had been described as New Zealand's "early colonial gentry" – the well-educated and aristocratic land-owners and commercial magnates. It was this group that most strongly opposed the Liberal Party, denouncing its policies as an attempt by the unsuccessful to rob the prosperous.[7][12]

In power, the Liberals enacted a large number of social, health, and economic reforms. This was made possible by their unity – previously, reforms had stalled due to the need for long and complex negotiations to win support from individual MPs. Among the changes introduced were land reforms, progressive taxes on land and income, and legislation to improve the working conditions of urban labourers.[13][14] Many of the Liberal Party's policies were described as "socialist" by both its opponents and sympathetic international observers such as André Siegfried and Albert Métin, but there is debate over whether this label is valid.[15] William Pember Reeves, a Liberal Party politician and theorist, said that while the party supported an active role for the state, particularly in social matters, it did not in any way seek to discourage or inhibit private enterprise. Many historians have claimed that the Liberal Party's policies were based more on pragmatism than on ideology, although politicians such as Ballance and Reeves definitely had theories behind their actions.

Dominance

In 1893, John Ballance died unexpectedly, leaving the Liberal Party's leadership open. It is believed that Ballance wished Robert Stout, a colleague known for his liberal views, to succeed him, but in the end, the leadership passed to Richard Seddon. Although Seddon went on to become New Zealand's longest serving Prime Minister, he was not as highly regarded by the Liberal Party as he was by the general public. In particular, Seddon's social views were more conservative than those of Ballance or Stout, and he was seen by many as having a controlling and autocratic style of management. Seddon had originally assumed the leadership on an interim basis, with a full caucus vote intended for a later date, but no such vote was ever held. Stout and his liberal colleagues challenged this, but were unsuccessful – although many in the party were uneasy about Seddon's views, Seddon himself was charismatic, and it was correctly predicted that he would win considerable support from the public.[16][17]

An early clash between the Liberal Party's two wings came over the issue of women's suffrage. Ballance had been a strong supporter of the suffrage movement, having proclaimed his belief in the "absolute equality of the sexes", but Seddon was opposed. Considerable bitterness arose over the matter, with Stout and his allies strongly promoting suffrage despite Seddon's hostility. In the end, the pro-suffrage MPs were able to get enough support to pass the measure despite their leader actively campaigning against it.[18][19]

In other matters, however, Seddon was more closely aligned with Ballance's original vision. Many of the party's earlier reforms were strengthened. William Pember Reeves, now the party's foremost theorist, promoted a number of other similar reforms including the world's first compulsory system of state arbitration.[20] Reeve's efforts to introduce further union-friendly regulation created friction with Seddon, who disagreed with Reeves's intellectual view of political matters and was nervous about public toleration of the Liberals' pace of reforms. In 1895, Reeves resigned from his cabinet portfolio and became New Zealand's Agent-General (later High Commissioner) in the United Kingdom.[21]

Seddon also introduced a number of new welfare and pension measures, sometimes compared to the welfare reforms of the UK Liberal Party under Prime Minister H. H. Asquith in the United Kingdom. These measures eventually formed the basis on which the Labour Party's Michael Joseph Savage built the modern NZ welfare state. Seddon was extremely popular with common New Zealanders, and under his particular brand of populism, the Liberal Party established itself as the dominant party of New Zealand politics.

In 1899, the Liberal and Labour Federation was formed to select candidates approved by the party leadership and ensure that they promoted a consistent and approved set of policies. Candidate selection was ultimately determined by Seddon. The Federation was New Zealand's first national party political organisation, and had most of the features of a modern political party, including: subscribing members, a central council and an annual conference.[22]

Agrarianism

The Liberal Party aggressively promoted agrarianism during their dominant period from 1891 to 1912. They believed a truly democratic society had to rest on the foundations of an independent land-owning class of small farmers, as opposed to large farms with hired help, or urban factories. The landed gentry and aristocracy ruled the United Kingdom at this point in time. New Zealand never had an aristocracy but it did have wealthy landowners who largely controlled politics prior to 1891. The Liberal Party set out to change that by a policy it called "populism." Seddon had proclaimed the goal as early as 1884: "It is the rich and the poor; it is the wealthy and the landowners against the middle and labouring classes. That, Sir, shows the real political position of New Zealand."[23]

The Liberal strategy was to create a large class of small land-owning farmers who supported Liberal ideals. To obtain land for farmers the Liberal government, over a twenty-year period from 1891 to 1911 purchased 3.1 million acres (13,000 km2) of Maori land. The government also purchased 1.3 million acres (5,300 km2) from large estate holders for subdivision and closer settlement by small farmers. In South Island, the 84,000 acre Cheviot estate was broken up. In eleven years, 176 South Island pastoral estates were broken up; totalling 940,000 acres (3,800 km2) and divided into 3,500 farm.[24] The main method used to persuade pastoralists to sell was taxation of large land holdings. Coupled with this, many of the early pioneer estate owners were dying and the estates were being divided amongst their often large families. Equal partibility was the norm amongst families of Irish and middle-class English backgrounds.[25]

The success of the small farm enterprises went hand-in-hand with the rapid development of dairy farming, underpinned by the invention of refrigerated shipping in 1882. The Advances to Settlers Act of 1894 provided low-interest mortgages, while the Agriculture Department disseminated information on the best farming methods. The Liberals proclaimed success in forging an egalitarian, anti-monopoly land policy. The policy built up support for the Liberal Party in rural North Island electorates. By 1903, the Liberals were so dominant that there was no longer an organised opposition in Parliament.[26][27]

Gradual decline

Slowly, however, the Liberal Party's dominance began to erode. The "reforming fires" of the party, the basis of their original success, were dying, and there was little innovation in the field of policy. In 1896, a splinter group formed the Radical Party, to advocate more "advanced" policies than Seddon's. In 1905, a similar group formed the New Liberal Party to push for more "progressive" policies, but this group was defunct by the time of the 1908 NZ general election.

In 1906, Seddon died. Joseph Ward, his replacement (after a period of stewardship by William Hall-Jones), did not have the same charismatic flair. Increasingly, the Liberals found themselves losing support on two fronts – farmers, having obtained their goal of land reform, were gradually drifting to the conservative opposition, and workers, having become dissatisfied at the slowed pace of reform, were beginning to talk of an independent labour party.[28][29]

The Liberals were aware of the problem facing them, and attempted to counter it. As early as 1899, Seddon had founded the "Liberal and Labour Federation", an attempt to relaunch Ballance's old Liberal Federation with more support from workers.[30] Later, Joseph Ward declared a "holiday" from socially progressive legislation, halting any changes that might drive away conservatives. The party also introduced runoff voting (second ballot), hoping to reduce the chances of labour-aligned candidates from splitting the non-conservative vote, but this only applied in the 1908 and 1911 general elections, and the rule was repealed in 1913.[31]

In 1909, the conservative opposition (led by William Massey) established the Reform Party, a united organisation to challenge the Liberals. At the same time, the first noteworthy labour-orientated parties were appearing, saying that the Liberals were no longer able to provide the reforms that workers needed. The Liberal Party found itself torn between its two primary constituencies, unable to satisfy both.[32][33] This coincided with a gradual decline in the organisational standards of the Liberal Party, with the situation having reached the point where in some cases, multiple "Liberal" candidates were contesting the same electoral race.[34]

At the 1911 general election, the Liberal Party won four fewer seats than the Reform Party, but managed to remain in power with the support of some labour-aligned MPs and independents. In 1912, Sir Joseph Ward stepped down and was replaced by Thomas Mackenzie, who defeated George Laurenson by 22 votes to 9 (John A. Millar did not stand in this leadership ballot on 22 March). In July 1912, coupled with the defection of some Liberal MPs like Millar; this arrangement collapsed, and twenty-one years of Liberal Party government came to an end.[35][36][37]

Opposition

The Liberals adopted a number of new policies in an attempt to win back votes, including an increase in land tax (supported by the labour movement) and the introduction of proportional representation, with Grey Lynn MP George Fowlds' Proportional Representation And Effective Voting Bill 1911 (86–1).[38][39] However, the foundation of the Labour Party in 1916 deprived the Liberals of many votes from working-class areas, while the business world, concerned at Labour's rise, was uniting behind Reform's "anti-socialism" platform. The Liberal Party was accused by Labour of being a party of the elite, and by Reform of having socialist sympathies – between the two, many predicted that the Liberals would continue to decline. Several leadership changes – back to Ward in mid-1912, to William MacDonald and then Thomas Wilford in 1920, and to George Forbes in 1925 – failed to revive the party's fortunes. In June 1926, the Liberals were overtaken as the second-largest party and official opposition by Labour who won the 1926 by-election for Eden.

Gradually, the Liberal Party's organisation decayed to the point of collapse. In 1927, a faction of the Liberal Party formed a new organisation, which was eventually named the United Party. To the considerable surprise of most observers, including many members of the party itself, United won a considerable victory, and formed a government in 1928. Later, United would reluctantly merge with Reform to counter the Labour Party. The result of this merger, the National Party, remains prominent in New Zealand politics. Both the National and the Labour Parties, the two main powers since 1936, claim to be the Liberal's successors.[40][41]

Parliamentary leaders

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Key:

Liberal

Conservatives

Reform

PM: Prime Minister

LO: Leader of the Opposition

†: Died in office

| No. | Leader | Portrait | Term of office | Position | Prime Minister | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John Ballance |  |

2 July 1889 | 27 April 1893† | LO 1889–1890 | Atkinson | ||

| PM 1890–1893 | Ballance | |||||||

| 2 | Richard Seddon |  |

1 May 1893 | 10 June 1906† | PM 1893–1906 | Seddon | ||

| 3 | William Hall-Jones |  |

21 June 1906 | 6 August 1906 | PM 1906 | Hall-Jones | ||

| 4 | Joseph Ward |  |

6 August 1906 | 12 March 1912 | PM 1906–1912 | Ward | ||

| 5 | Thomas Mackenzie |  |

28 March 1912 | 10 July 1912 | PM 1912 | Mackenzie | ||

| (4) | Joseph Ward |  |

11 September 1913 | 27 November 1919 | LO 1913–1919 | Massey | ||

| 6 | William MacDonald |  |

14 January 1920 | 31 August 1920† | LO 1920 | |||

| 7 | Thomas Wilford |  |

8 September 1920 | 13 August 1925 | LO 1920–1925 | |||

| Bell | ||||||||

| Coates | ||||||||

| 8 | George Forbes |  |

13 August 1925 | 18 September 1928 | LO 1925 | |||

Electoral results

| Part of a series on |

| Organised labour |

|---|

|

| Election | # of votes | % of vote | # of seats won | Government/opposition? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 76,548 | 56.1 | 40 / 74 | Government |

| 1893 | 175,814 | 57.80 | 51 / 74 | |

| 1896 | 184,650 | 54.78 | 39 / 74 | |

| 1899 | 204,331 | 52.71 | 49 / 74 | |

| 1902 | 215,378 | 51.8 | 47 / 80 | |

| 1905 | 219,144 | 53.1 | 58 / 80 | |

| 1908 | 315,220 | 58.7% | 50 / 80 | |

| 1911 | 163,401 | 34.23 | 33 / 80 | Opposition |

| 1914 | 227,706 | 43.1 | 34 / 80 | |

| 1919 | 155,708 | 28.7 | 19 / 80 | |

| 1922 | 166,708 | 26.26 | 22 / 80 | |

| 1925 | 143,931 | 20.94 | 11 / 80 | |

See also

References

- Bassett, Michael (1982). Three Party Politics in New Zealand, 1911–1931. Auckland: Historical Publications. ISBN 0868700061.

- Burdon, R.M. (1965). The New Dominion. A Social and Political History of New Zealand, 1918–1939. Wellington: A. H. & A. W. Reed.

- Burdon, R.M. (1955). King Dick: A Biography of Richard John Seddon. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs.

- Campbell, Christopher (1975). "The "Working Class" and the Liberal Party in 1890" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of History. 9 (1): 41–51.

- Fairburn, Miles; Haslett, Stephen (May 2005). "Voter Behaviour and the Decline of the Liberals in Britain and New Zealand, 1911-29: Some Comparisons". Social History. 30 (2): 195–217. doi:10.1080/03071020500082868. JSTOR 4287190. S2CID 143826033. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Gustafson, Barry (1986). The First 50 Years: A History of New Zealand National Party. Auckland: Reed Methuen Publishers. ISBN 0474001776.

- Hamer, David A. (1988). The New Zealand Liberals: The Years of Power, 1891–1912. Auckland: Auckland University Press. ISBN 1-86940-014-3. OCLC 18420103.

- King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand (First ed.). Auckland: Penguin Books. ISBN 0143018671.

- Nagel, Jack (April 1993). "Populism, Heresthetics and Political Stability: Richard Seddon and the Art of Majority Rule". British Journal of Political Science. 23 (2): 139–174. doi:10.1017/S0007123400009716. JSTOR 194246. S2CID 154806794. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Sinclair, Keith; Dalziel, Raewyn (2000). A History of New Zealand: Revised Edition (Fifth revised ed.). Auckland: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140298758.

Notes

- ↑ "Rīpera - te Aka Māori Dictionary".

- ↑ Gordon Anderson and Michael Quinlan, "The Changing Role of the State: Regulating Work in Australia and New Zealand 1788–2007," Labour History (2008), Issue 95, pp 111–132.

- ↑ "A brief history of the minimum wage in New Zealand". Newshub. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ↑ Peter J. Coleman, Progressivism and the World of Reform: New Zealand and the Origins of the American Welfare State (1987)

- ↑ Peter J. Coleman, "New Zealand Liberalism and the Origins of the American Welfare State," Journal of American History (1982) 69#2 pp. 372–391 in JSTOR

- ↑ Peter J. Coleman, "The New Zealand Welfare State: Origins and Reflections," Continuity (1981), Issue 2, pp 43–61

- 1 2 Sinclair 2000, p. 169-176.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 259-261.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 261-262.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 261.

- ↑ Hamer 1988, pp. 83–85, 9.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 239, 260-261.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 261-281.

- ↑ Sinclair 2000, p. 187-195.

- ↑ Sinclair 2000, p. 182-183, 194-196.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 262-265.

- ↑ Sinclair 2000, p. 184-185.

- ↑ Sinclair 2000, p. 192-193.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 265-267.

- ↑ Sinclair 2000, p. 190-191.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 268-269.

- ↑ Atkinson, Neill (2003), Adventures in Democracy: A History of the Vote in New Zealand, Otago University Press, p.103.

- ↑ Leslie Lipson (1948). The Politics of Equality: New Zealand's Adventures in Democracy. U. of Chicago Press.

- ↑ The Canoes of Kupe. R. McIntyre. Fraser Books. Masterton. 2012. p162.

- ↑ The Canoes of Kupe. p 163.

- ↑ James Belich, Paradise Reforged: A history of the New Zealanders (2001) pp 39–46

- ↑ Tom Brooking, "'Busting Up' the Greatest Estate of All: Liberal Maori Land Policy, 1891–1911," New Zealand Journal of History (1992) 26#1 pp 78–98 online

- ↑ Sinclair 2000, p. 208-216.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 278-280.

- ↑ Sinclair 2000, p. 209.

- ↑ Hamer 1988, pp. 308–312, 335–340.

- ↑ Sinclair 2000, p. 216-220, 208-212.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 279-280.

- ↑ Hamer 1988, pp. 321–322.

- ↑ Bassett 1982, p. 3-14.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 280.

- ↑ Hamer 1988, pp. 329–354.

- ↑ "Parliamentary Voting Systems in New Zealand and the Referendum on MMP". New Zealand Parliament. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ "Proportional Representation And Effective Voting Bill 1911 (86–1)". New Zealand Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Foster, John. "Liberal Party". In McLintock, A. H. (ed.). An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage / Te Manatū Taonga. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Gustafson 1986, p. 2-7.