Licchavi | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 400 CE–c. 750 CE | |||||||||||||||||||

Coinage of Licchavi king Amshuverma (605–621 CE). Obverse: winged lion, with Brahmi legend Śri Amśurvarma "Lord Amshurvarma". Reverse: Bull with Brahmi legend Kāmadēhi ("Incarnation of Kāma").[2]

| |||||||||||||||||||

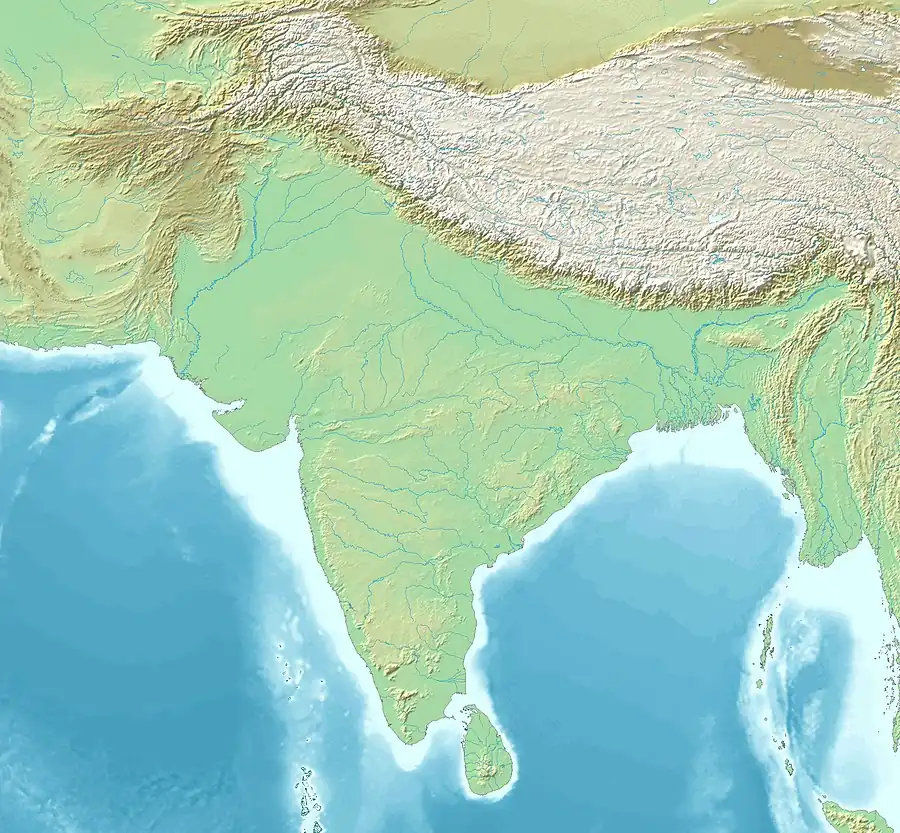

South Asia 600 CE ◁ ▷ Fragmented South Asian polities circa 600 CE, after the retreat of the Alchon Huns.[3] | |||||||||||||||||||

| Government | monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 400 CE | ||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 750 CE | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Nepal | ||||||||||||||||||

Obverse: Kumaradeva and Chandragupta standing, legend to the left Śrī Kumāradevā, to the right

Reverse: Goddess seated on lion, with the legend

Licchavi (also Lichchhavi, Lichavi) was a kingdom which existed in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal from approximately 400 to 750 CE. The Licchavi clan originated from Vaishali,[5] and conquered Kathmandu Valley.[6][7] The Licchavis were ruled by a maharaja, aided by a prime minister and other royal officials, but in practice local communities were controlled by caste councils.[8]

The ruling period of this dynasty was called the Golden Period of Nepal. A table of the evolution of certain Gupta characters used in Licchavi inscriptions prepared by Gautamavajra Vajrācārya can be found online.[9]

Records

It is believed that a branch of the Licchavi clan, having lost their political fortune and military power in Vaishali (Bihar),[10] came to Kathmandu and had marital relation with Naga-Kirati clan (Nagvanshi) eg. Queen of Mandeva Shree Vogini and started to rule in Nepal. Source.They also battled with local militias in Chyasal to gain control of Nepal. In the Buddhist Pali canon, the Licchavi are mentioned in a number of discourses, most notably the Licchavi Sutta,[11] the popular Ratana Sutta[12] and the fourth chapter of the Petavatthu.[13] The Mahayana Vimalakirti Sutra also spoke of the city of Vaishali as where the lay Licchavi bodhisattva Vimalakirti was residing.[14]

In the 4th century CE, during the reign of the Gupta emperor Samudragupta, the "Nepalas" are mentioned among the tribes subjugated by him:

(Samudragupta, whose) formidable rule was propitiated with the payment of all tributes, execution of orders and visits (to his court) for obeisance by such frontier rulers as those of Samataṭa, Ḍavāka, Kāmarūpa, Nēpāla, and Kartṛipura, and, by the Mālavas, Ārjunāyanas, Yaudhēyas, Mādrakas, Ābhīras, Prārjunas, Sanakānīkas, Kākas, Kharaparikas and other (tribes)."

Samudragupta was a son of the Gupta Emperor Chandragupta I and the Licchavi princess Kumaradevi.[16] Gold coins bearing portraits of Chandragupta and Kumaradevi have been discovered at Mathura, Ayodhya, Lucknow, Sitapur, Tanda, Ghazipur, and Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh; Bayana in Rajasthan; and Hajipur in Bihar. The obverse of these coins depicts portraits of Chandragupta and Kumaradevi, with their names in the Gupta script. The reverse shows a goddess seated on a lion, with the legend "Li-ccha-va-yah" (![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 𑁊, "the Lichchhavis").[16][17]

𑁊, "the Lichchhavis").[16][17]

The earliest known physical record of the kingdom is an inscription of Mānadeva, which dates from 464. It mentions three preceding rulers, suggesting that the Licchavi dynasty began in the late 4th century.

Government

The Licchavi were ruled by a Maharaja ("great king"), who was aided by a prime minister, in charge of the military and of other ministers. Nobles known as samanta influenced the court whilst simultaneously managing their own landholdings and militia. At one point, between approximately 605 and 641, a prime minister called Amshuverma assumed the throne.

The population provided land taxes and conscript labour (vishti) to support the government. Most local administration was performed by village heads or leading families. Many kings ruled but the popular one were Manadeva, Amshuverma etc.

Economy

The economy was agricultural, relying on rice and other grains as staples. Villages (grama) were grouped into dranga for administration. Lands were owned by the royal family and nobles. Trade was also very important, with many trading settlements.

Geography

Domain

Settlements already filled the entire valley during the Licchavi period. Further settlement extended east toward Banepa, west toward Tistung Deurali, and northwest toward present-day Gorkha.

Rulers

The following list was adapted from The Licchavi Kings, by Tamot & Alsop,[18] and is approximate only, especially with respect to dates.

- 185 Jayavarmā (also Jayadeva I)

- Vasurāja (also Vasudatta Varmā)

- c. 400 Vṛṣadeva (also Vishvadeva)

- c. 425 Shaṅkaradeva I

- c. 450 Dharmadeva

- 464-505 Mānadeva I

- 505-506 Mahīdeva (few sources)

- 506-532 Vasantadeva

- Manudeva (probable chronology)

- 538 Vāmanadeva (also Vardhamānadeva)

- 545 Rāmadeva

- Amaradeva

- Guṇakāmadeva

- 560-565 Gaṇadeva

- 567-c. 590 Bhaumagupta (also Bhūmigupta, probably not a king)

- 567-573 Gaṅgādeva

- 575/576 Mānadeva II (few sources)

- 590-604 Shivadeva I

- 605-621 Aṃshuvarmā

- 621 Udayadeva

- 624-625 Dhruvadeva

- 631-633 Bhīmārjunadeva, Jiṣṇugupta

- 635 Viṣṇugupta - Jiṣṇugupta

- 640-641 Bhīmārjunadeva / Viṣṇugupta

- 643-679 Narendradeva

- 694-705 Shivadeva II

- 713-733 Jayadeva II

- 748-749 Shaṅkaradeva II

- 756 Mānadeva III

- 826 Balirāja

- 847 Baladeva

- 875–879 Mandeva IV[19]

See also

| History of Nepal |

|---|

|

|

|

References

- Smith, Vincent Arthur; Edwardes, S. M. (Stephen Meredyth) (1924). The early history of India : from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan conquest, including the invasion of Alexander the Great. Oxford : Clarendon Press. p. Plate 2.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur; Edwardes, S. M. (Stephen Meredyth) (1924). The early history of India : from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan conquest, including the invasion of Alexander the Great. Oxford : Clarendon Press. p. Plate 2.

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 26,146. ISBN 0226742210.

- ↑ Allen, John (1914). Catalogue of the coins of the Gupta dynasties. p. 8.

- ↑ Journal. 1902.

- ↑ Kaplan, Robert B.; Baldauf, Richard B. (2008). Language Planning and Policy in Asia: Japan, Nepal, Taiwan and Chinese characters. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 978-1-84769-095-1.

- ↑ India), Asiatic Society (Kolkata (1902). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- ↑ Anil Kathuria, ed. (2007). Encyclopaedia of Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet: Nepal. Anoml Publications. p. 32.

- ↑ "Gautamavajra Vajrācārya, "Recently Discovered Inscriptions of Licchavi Nepal", Kathmandu Kailash - Journal of Himalayan Studies. Volume 1, Number 2, 1973. (pp. 117-134)". Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- ↑ India), Asiatic Society (Kolkata (1902). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- ↑ "Licchavi Sutta," translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu (2004).

- ↑ "Ratana Sutta: The Jewel Discourse," translated from the Pali by Piyadassi Thera (1999).

- ↑ "Petavatthu, Fourth Chapter, in Pali". Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ↑ Thurman, Robert. "VIMALAKIRTI NIRDESA SUTRA". Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ Fleet, John Faithfull (1888). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol. 3. pp. 6–10.

- 1 2 R. C. Majumdar 1981, p. 11.

- ↑ Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 90.

- ↑ Tamot, Kashinath and Alsop, Ian. "A Kushan-period Sculpture, The Licchavi Kings", Asianart.com

- ↑ Shrestha, Nanda R. (2003). Historical dictionary of Nepal. Keshav Bhattarai. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4797-3. OCLC 51931102.

Sources

- Ashvini Agrawal (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.

- R. C. Majumdar (1981). A Comprehensive History of India. Vol. 3, Part I: A.D. 300-985. Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. OCLC 34008529.

External links

- Tamot, Kashinath and Alsop, Ian. "A Kushan-period Sculpture, The Licchavi Kings", Asianart.com

- History of Nepal, Thamel.com

- "Nepal: The Early Kingdom of the Licchavis, 400-750", Library of Congress Countryreports.org (September, 1991)

- Vajrācārya, Gautamavajra, "Recently Discovered Inscriptions of Licchavi, Nepal", Kailash - Journal of Himalayan Studies, Volume 1, Number 2, 1973. (pp. 117-134)