| Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen | |

|---|---|

| Song cycle by Gustav Mahler | |

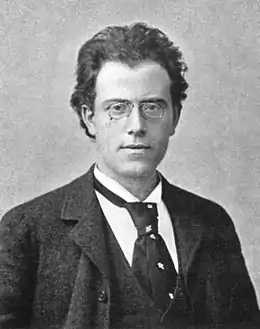

The composer in 1892 | |

| English | Songs of a Wayfarer |

| Related | First Symphony |

| Text | by Mahler |

| Language | German |

| Based on | Des Knaben Wunderhorn |

| Composed | 1884–85, later revised |

| Performed | 16 March 1896 (orchestral version) |

| Published | 1897 |

| Movements | four |

| Scoring |

|

Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) is a song cycle by Gustav Mahler on his own texts. The cycle of four lieder for medium voice (often performed by women as well as men) was written around 1884–85 in the wake of Mahler's unhappy love for soprano Johanna Richter, whom he met as the conductor of the opera house in Kassel, Germany,[1] and orchestrated and revised in the 1890s.

Introduction

The work's compositional history is complex and difficult to trace.[2] Mahler appears to have begun composing the songs in December 1884 and to have completed them in 1885.[3] He subjected the score to a great deal of revision, probably between 1885 and 1886, and some time in the early 1890s orchestrated the original piano accompaniments. As a result of this situation, various discrepancies exist between the different sources.

It appears to have been in the orchestral version that the cycle was first performed on 16 March 1896 by the Dutch baritone Anton Sistermans with the Berlin Philharmonic and Mahler conducting, but possible indications of an earlier voice-and-piano performance cannot be discounted. The work was published in 1897 and is one of Mahler's best-known compositions.

The lyrics are by the composer himself, though they are influenced by Des Knaben Wunderhorn, a collection of German folk poetry that was one of Mahler's favorite books, and the first song is actually based on the Wunderhorn poem "Wann [sic] mein Schatz".

In this song cycle, Mahler extensively uses progressive tonality. Each of the four songs ends in a different key: (1) D minor to G minor; (2) D major to F-sharp major; (3) D minor to E-flat minor; (4) E minor to F minor.

There are strong connections between this work and Mahler's Symphony No. 1, with the main theme of the second song being the main theme of the first movement and the final verse of the fourth song reappearing in the third movement as a contemplative interruption of the funeral march.[4]

In addition to the solo baritone, the work is scored for 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (both doubling English horn), 3 clarinets (3rd doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones timpani, percussion (bass drum, cymbals, triangle, tam-tam, and glockenspiel) harp, and strings.

Contents

I – "Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht" ("When My Sweetheart is Married")

The first song is entitled "Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht" ("When My Sweetheart is Married"),[5] and the text discusses the Wayfarer's grief at losing his love to another. He remarks on the beauty of the surrounding world, but how that cannot keep him from having sad dreams. The orchestral texture is bittersweet, using double reed instruments, clarinets and strings. It begins in D minor and ends in G minor.

Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht,

Fröhliche Hochzeit macht,

Hab' ich meinen traurigen Tag!

Geh' ich in mein Kämmerlein,

Dunkles Kämmerlein,

Weine, wein' um meinen Schatz,

Um meinen lieben Schatz!

Blümlein blau! Verdorre nicht!

Vöglein süß!

Du singst auf grüner Heide.

Ach, wie ist die Welt so schön!

Ziküth! Ziküth!

Singet nicht! Blühet nicht!

Lenz ist ja vorbei!

Alles Singen ist nun aus!

Des Abends, wenn ich schlafen geh',

Denk' ich an mein Leide!

An mein Leide!

II – "Ging heut' Morgen über's Feld" ("I Went This Morning over the Field")

The second song, "Ging heut' Morgen über's Feld" ("I Went This Morning over the Field"), contains the happiest music of the work. Indeed, it is a song of joy and wonder at the beauty of nature in simple actions like birdsong and dew on the grass. "Is it not a lovely world?" is a refrain. However, the Wayfarer is reminded at the end that despite this beauty, his happiness will not blossom anymore now that his love is gone. This movement is orchestrated delicately, making use of high strings and flutes, as well as a fair amount of triangle. The melody of this movement, as well as much of the orchestration, was later reused by Mahler and developed into the 'A' theme of the first movement of his Symphony No. 1. It begins in D major and ends in F♯ major.

Ging heut' Morgen über's Feld,

Tau noch auf den Gräsern hing;

Sprach zu mir der lust'ge Fink:

"Ei du! Gelt? Guten Morgen! Ei gelt?

Du! Wird's nicht eine schöne Welt?

Zink! Zink! Schön und flink!

Wie mir doch die Welt gefällt!"

Auch die Glockenblum' am Feld

Hat mir lustig, guter Ding',

Mit den Glöckchen, klinge, kling,

Ihren Morgengruß geschellt:

"Wird's nicht eine schöne Welt?

Kling, kling! Schönes Ding!

Wie mir doch die Welt gefällt! Heia!"

Und da fing im Sonnenschein

Gleich die Welt zu funkeln an;

Alles Ton und Farbe gewann

Im Sonnenschein!

Blum' und Vogel, groß und Klein!

"Guten Tag, ist's nicht eine schöne Welt?

Ei du, gelt? Schöne Welt!"

Nun fängt auch mein Glück wohl an?

Nein, nein, das ich mein',

Mir nimmer blühen kann!

III – "Ich hab' ein glühend Messer" ("I Have a Gleaming Knife")

The third song is a full display of despair. Entitled "Ich hab' ein glühend Messer" ("I Have a Gleaming Knife"), the Wayfarer likens his agony of lost love to having an actual metal blade piercing his heart. He obsesses to the point where everything in the environment reminds him of some aspect of his love, and he wishes he actually had the knife. Note: while the translation of "glühend" as gleaming is not totally incorrect, "gleaming" misses an important point: "glühend" includes an element of heat, as in "glowing with heat"; a potentially better translation might be any of "glowing", "burning", "scorching". This is not just a bright-looking ("gleaming") knife, but one that burns and scorches. The music is intense and driving, fitting to the agonized nature of the Wayfarer's obsession. It begins in D minor and ends in E♭ minor.

Ich hab' ein glühend Messer,

Ein Messer in meiner Brust,

O weh! Das schneid't so tief

in jede Freud' und jede Lust.

Ach, was ist das für ein böser Gast!

Nimmer hält er Ruh',

nimmer hält er Rast,

Nicht bei Tag, noch bei Nacht,

wenn ich schlief!

O weh!

Wenn ich den Himmel seh',

Seh' ich zwei blaue Augen stehn!

O weh! Wenn ich im gelben Felde geh',

Seh' ich von fern das blonde Haar

Im Winde weh'n!

O weh!

Wenn ich aus dem Traum auffahr'

Und höre klingen ihr silbern Lachen,

O weh!

Ich wollt', ich läg' auf der Schwarzen Bahr',

Könnt' nimmer die Augen aufmachen!

IV – "Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz" ("The Two Blue Eyes of my Beloved")

The final song culminates in a resolution. The music, also reused in the First Symphony (in the slow movement), is subdued and gentle, lyrical and often reminiscent of a chorale in its harmonies. Its title, "Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz" ("The Two Blue Eyes of my Beloved"), deals with how the image of those eyes has caused the Wayfarer so much grief that he can no longer stand to be in the environment. He describes lying down under a linden tree, finding rest for the first time and allowing the flowers to fall on him; and somehow (beyond his own comprehension) everything was well again: "Everything: love and grief, and world, and dream!" It begins in E minor and ends in F minor.

Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz,

Die haben mich in die weite Welt geschickt.

Da mußt ich Abschied nehmen vom allerliebsten Platz!

O Augen blau, warum habt ihr mich angeblickt?

Nun hab' ich ewig Leid und Grämen!

Ich bin ausgegangen in stiller Nacht

wohl über die dunkle Heide.

Hat mir niemand Ade gesagt

Ade!

Mein Gesell' war Lieb und Leide!

Auf der Straße steht ein Lindenbaum,

Da hab' ich zum ersten Mal im Schlaf geruht!

Unter dem Lindenbaum,

Der hat seine Blüten über mich geschneit,

Da wußt' ich nicht, wie das Leben tut,

War alles, alles wieder gut!

Alles! Alles, Lieb und Leid

Und Welt und Traum!

Translation of the title

Although Songs of a Wayfarer is the title by which the cycle is generally known in English, Fritz Spiegl has observed that German "Geselle" actually means "journeyman", i.e., one who has completed an apprenticeship with a master in a trade or craft, but is not yet a master himself; journeymen in German-speaking countries traditionally traveled from town to town to gain experience with various masters. A more accurate translation, therefore, would be Songs of a Travelling Journeyman. The title hints at an autobiographical aspect of the work; as a young, newly qualified conductor (and budding composer), Mahler was himself at this time in a stage somewhere between 'apprentice' and recognized 'master' and had been moving from town to town (Bad Hall, Laibach, Olmütz, Vienna, Kassel). All the while, he was honing his skills and learning from masters in his field.

Discography

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau - Mahler: Symphony No. 1 in D major / Songs of a Wayfarer - Rafael Kubelík and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon 4497352, 1968

- Frederica von Stade and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Davis, Columbia, 1979

- Jessye Norman - Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A Minor / Songs of a Wayfarer - Bernard Haitink and the Berliner Philharmoniker, Philips, 1989

- Thomas Quasthoff - Mahler: Songs of a Wayfarer / Kindertotenlieder / Des Knaben Wunderhorn - Gary Bertini and the Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra, Chandos, C71124, 2010

- Thomas Hampson - Keeping Score- Gustav Mahler: Origins - Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, Warner Classics, 2011.

Further reading

- Ingo Müller: "Eins in Allem und Alles in Einem": Zur Ästhetik von Gedicht- und Liederzyklus im Lichte romantischer Universalpoesie. In: Günter Schnitzler und Achim Aurnhammer (Hrsg.): Wort und Ton. Freiburg i. Br. 2011 (= Rombach Wissenschaften: Reihe Litterae. Bd. 173), S. 243–274.

Notes and references

- ↑ Seckerson, Edward. Mahler. Omnibus Press, 1984. p. 30.

- ↑ "Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) – Introduction Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen". www.gustav-mahler.eu. Retrieved 2018-08-12.

- ↑ "Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen,… | Details | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 2018-08-12.

- ↑ Proms Programme Note

- ↑ "Details". smartsoloist.com. Retrieved 2018-08-12.