Sir Lislebone Long (1613–1659), was a supporter of the Parliamentary cause during the English Civil War, but he was a Presbyterian and he resisted Pride's Purge and although not secluded by Pride, he shortly afterwards absented himself for a short while from the House. After the regicide of Charles I, in which he took no part, he was an active member of the three Protectorate parliaments and was knighted by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.

Biography

Lislebone Long baptised Loveban, was born at Beckington, Somerset, the son of William Long of Stratton on the Fosse and Mary Lovibond. He graduated from Magdalen Hall, Oxford, 1630–31 with a B.A. and was called to the bar at Lincoln's Inn, 1640

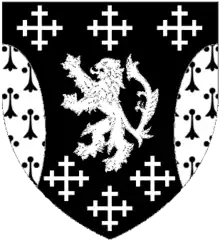

Long was descended from the Longs of Wiltshire. In local affairs Long identified both before and during the Civil War with at least one of his Wiltshire relatives, Sir Walter Long, 1st Baronet of Whaddon who was an outspoken critic of the King. Like his cousin, he was a presbyterian and became an elder in parliament's presbyterian national church, with a later appointment to the parliamentary committee charged with settling the form of church government in England (1648). Following the end of royalist occupation, parliament's county committee in Somerset was revived in 1645, and Long was appointed as a member.

Long was known for his moderate stance in politics, which was also demonstrated in parliament, following his election to the Long Parliament as a recruiter MP for Wells (1645–53). He voiced his strong opposition to Pride's Purge (6 December 1648), and on the day following the purge, he acted as a teller on a critical vote. After a few occasional appearances, he eventually absented himself from the House of Commons in protest. He became a conformist by taking his dissent and resuming his seat in the Rump Parliament, although he played no part in the trial and execution of Charles I. From that point on he played an active role in the work of committees, his moderating influence reflected in government policies.

Long was also a regular participant in parliamentary debates. In the First Protectorate Parliament (1654–5), he served as MP for Wells; in the Second Protectorate Parliament (1656–8), for Somerset; and again for Wells in Richard Cromwell's parliament (the Third Protectorate Parliament) (1659). He was described by one of his contemporaries as 'a very sober, discreet gentleman, and a good lawyer', making intelligent contributions during sessions of the Cromwellian parliaments on points of law, precedent, and procedure.

Highly respected within his local community, he was appointed Justice of the Peace (JP) for Somerset 1654–9, elected Recorder of London in 1655, knighted by Oliver Cromwell in 1656, and that same year was appointed treasurer of Lincoln's Inn, a Master of Requests, and a Commissioner of Treasons.

On 9 March 1659, the speaker of Richard Cromwell's parliament, Chaloner Chute, suddenly became indisposed as a result of being "tired out with the long debates and late sitting" (Diary of Thomas Burton, 4.92). This was after a long nine days debate, during which the House sat through one entire night up to 10 p.m. As a tribute to the high regard in which he was held, Sir Lislebone was duly elected 'by general consent of the House' (JHC, 7.612) to take the chair during the speaker's illness. Just one week later on 16 March, Burton notes in his diary that Long "being very sick, could not attend". He died later the same day and was buried at Stratton on the Fosse, leaving an estate which included a number of ecclesiastical and royalist lands purchased after confiscation by parliament.

Family

He had married on 18 February 1640 at London, Frances Mynne, daughter of John Mynne of Epsom.[2][3] They had two sons and two daughters. His wife died in 1691.

Further reading

Notes

- ↑ "Speaker Long, 1659". Baz Manning. September 2005. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ A pedigree of Mynne in relation to the manor of Horton, of which Woodecote Park was a sub-manor, may be found in Manning and Bray's History of Surrey.

- ↑ Bouchard 2012.

References

- Beavan, Arthur H. (1901). Imperial London.

- Bouchard, Brian (2012). "Woodcote Park".

- Wroughton, John (January 2008) [2004]. "Long, Lislebone (bap. 1613, d. 1659)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16972. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) The first edition of this text is available at Wikisource: . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

_(2022).svg.png.webp)