The emperors of the Han dynasty were the supreme heads of government during the second imperial dynasty of China; the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) followed the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) and preceded the Three Kingdoms (220–265 AD). The era is conventionally divided between the Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD) and Eastern Han (25–220 AD) periods.

The Han dynasty was founded by the peasant rebel leader (Liu Bang), known posthumously as Emperor Gao (r. 202 –195 BC) or Gaodi. The longest reigning emperor of the dynasty was Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BC), or Wudi, who reigned for 54 years. The dynasty was briefly interrupted by the Xin dynasty of the former regent Wang Mang, but he was killed during a rebellion on 6 October 23 AD.[2] The Han dynasty was reestablished by Liu Xiu, known posthumously as Emperor Guangwu (r. 25–57 AD) or Guangwu Di, who claimed the throne on 5 August 25 AD.[3][4] The last Han emperor, Emperor Xian (r. 189–220 AD), was a puppet monarch of Chancellor Cao Cao (155–220 AD), who dominated the court and was made King of Wei.[5] On 11 December 220, Cao's son Pi usurped the throne as Emperor Wen of Wei (r. 220–226 AD) and ended the Han dynasty.[6]

The emperor was the supreme head of government.[7] He appointed all of the highest-ranking officials in central, provincial, commandery, and county administrations.[8] He also functioned as a lawgiver, the highest court judge, commander-in-chief of the armed forces, and high priest of the state-sponsored religious cults.[9]

Naming conventions

Emperor

In ancient China, the rulers of the Shang (c. 1600 – c. 1050 BC) and Zhou (c. 1050 – 256 BC) dynasties were referred to as kings (王 wang).[11] By the time of the Zhou dynasty, they were also referred to as Sons of Heaven (天子 Tianzi).[11] By 221 BC, the King of Qin, Ying Zheng, conquered and united all the Warring States of ancient China. To elevate himself above the Shang and Zhou kings of old, he accepted the new title of emperor (皇帝 huangdi) and is known to posterity as the First Emperor of Qin (Qin Shi Huang). The new title of emperor was created by combining the titles for the Three Sovereigns (Sanhuang) and Five Emperors (Wudi) from Chinese mythology.[12] This title was used by each successive ruler of China until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911.[13]

Posthumous, temple, and era names

From the Shang to Sui (581–618 AD) dynasties, Chinese rulers (both kings and emperors) were referred to by their posthumous names in records and historical texts.[13] Temple names, first used during the reign of Emperor Jing of Han (r. 157–141 BC), were used exclusively in later records and historical texts when referring to emperors who reigned during the Tang (618–907 AD), Song (960–1279 AD), and Yuan (1271–1368 AD) dynasties.[14] During the Ming (1368–1644 AD) and Qing (1644–1911 AD) dynasties, a single era name was used for each emperor's reign and became the preferred way to refer to Ming and Qing emperors in historical texts.[14]

Use of the era name was formally adopted during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141–87 BC), yet its origins can be traced back further. The oldest method of recording years—which had existed since the Shang—set the first year of a ruler's reign as year one.[14] When an emperor died, the first year of a new reign period would begin.[14] This system was changed by the 4th century BC when the first year of a new reign period did not begin until the first day of the lunar New Year following a ruler's death.[14] When Duke Huiwen of Qin assumed the title of king in 324 BC, he changed the year count of his reign back to the first year.[14] For his newly adopted calendar established in 163 BC, Emperor Wen of Han (r. 180–157 BC) also set the year count of his reign back to the beginning.[15]

Since six was considered a lucky number, Han Emperors Jing and Wu changed the year count of their reigns back to the beginning every six years.[15] Since every six-year period was successively marked as yuannian (元年), eryuan (二元), sanyuan (三元), and so forth, this system was considered too cumbersome by the time it reached the fifth cycle wuyuan sannian (五元三年) in 114 BC.[15] In that year a government official suggested that the Han court retrospectively rename every "beginning" with new characters, a reform Emperor Wu accepted in 110 BC.[16] Since Emperor Wu had just performed the religious feng (封) sacrifice at Mount Taishan, he named the new era yuanfeng (元封). This event is regarded as the formal establishment of era names in Chinese history.[16] Emperor Wu changed the era name once more when he established the 'Great Beginning' (太初 Taichu) calendar in 104 BC.[17] From this point until the end of Western Han, the court established a new era name every four years of an emperor's reign. By Eastern Han there was no set interval for establishing new era names, which were often introduced for political reasons and celebrating auspicious events.[17]

Regents and empress dowagers

At times, especially when an infant emperor was placed on the throne, a regent, often the empress dowager or one of her male relatives, would assume the duties of the emperor until he reached his majority. Sometimes the empress dowager's faction—the consort clan—was overthrown in a coup d'état. For example, Empress Lü Zhi (d. 180 BC) was the de facto ruler of the court during the reigns of the child emperors Qianshao (r. 188–184 BC) and Houshao (r. 184–180 BC).[18] Her faction was overthrown during the Lü Clan Disturbance of 180 BC and Liu Heng was named emperor (posthumously known as Emperor Wen).[19] Before Emperor Wu died in 87 BC, he had invested Huo Guang (d. 68 BC), Jin Midi (d. 86 BC), and Shangguan Jie (上官桀)(d. 80 BC) with the power to govern as regents over his successor Emperor Zhao of Han (r. 87–74 BC). Huo Guang and Shangguan Jie were both grandfathers to Empress Shangguan (d. 37 BC), wife of Emperor Zhao, while the ethnically-Xiongnu Jin Midi was a former slave who had worked in an imperial stable. After Jin died and Shangguan was executed for treason, Huo Guang was the sole ruling regent. Following his death, the Huo-family faction was overthrown by Emperor Xuan of Han (r. 74–49 BC), in revenge for Huo Guang poisoning his wife Empress Xu Pingjun (d. 71 BC) so that he could marry Huo's daughter Empress Huo Chengjun (d. 54 BC).[20]

Since regents and empress dowagers were not officially counted as emperors of the Han dynasty, they are excluded from the list of emperors below.

List of emperors

Below is a complete list of emperors of the Han dynasty, including their personal, posthumous, and era names. Excluded from the list are de facto rulers such as regents and empress dowagers.

| Han dynasty sovereigns | |||||||||

| Sovereign | Personal name | Reigned from | Reigned until | Posthumous name[lower-alpha 1] | Era name | Range of years[lower-alpha 2] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Han dynasty (202 BC–9 AD) | |||||||||

| Emperor Gaozu | Liu Bang | 劉邦 | 28 February[22] 202 BC |

1 June[23] 195 BC[24] |

Emperor Gao | 高皇帝 | did not exist[25] | ||

| Emperor Hui | Liu Ying | 劉盈 | 23 June[26] 195 BC |

26 September[27] 188 BC[28] |

Emperor Xiaohui | 孝惠皇帝 | did not exist[25] | ||

| Emperor Qianshao | Liu Gong | 劉恭 | 19 October[27] 188 BC |

15 June[29] 184 BC[30] |

did not exist | did not exist[25] | |||

| Emperor Houshao | Liu Hong | 劉弘 | 15 June[29] 184 BC |

14 November[31] 180 BC[30] |

did not exist | did not exist[25] | |||

| Emperor Wen | Liu Heng | 劉恆 | 14 November[26] 180 BC |

6 July[32] 157 BC[33] |

Emperor Xiaowen | 孝文皇帝 | Qianyuan | 前元 | 179–164 BC[34] |

| Houyuan | 後元 | 163–156 BC[34] | |||||||

| Emperor Jing | Liu Qi | 劉啟 | 14 July[35] 157 BC |

9 March[36] 141 BC[33] |

Emperor Xiaojing | 孝景皇帝 | Qianyuan | 前元 | 156–150 BC[37] |

| Zhongyuan | 中元 | 149–143 BC[37] | |||||||

| Houyuan | 後元 | 143–141 BC[37] | |||||||

| Emperor Wu | Liu Che | 劉徹 | 10 March[26] 141 BC |

29 March[38] 87 BC[39] |

Emperor Xiaowu | 孝武皇帝 | Jianyuan | 建元 | 141–135 BC[40] |

| Yuanguang | 元光 | 134–129 BC[40] | |||||||

| Yuanshuo | 元朔 | 128–123 BC[40] | |||||||

| Yuanshou | 元狩 | 122–117 BC[40] | |||||||

| Yuanding | 元鼎 | 116–111 BC[40] | |||||||

| Yuanfeng | 元封 | 110–105 BC[40] | |||||||

| Taichu | 太初 | 104–101 BC[40] | |||||||

| Tianhan | 天漢 | 100–97 BC[40] | |||||||

| Taishi | 太始 | 96–93 BC[40] | |||||||

| Zhenghe | 征和 | 92–89 BC[40] | |||||||

| Houyuan | 後元 | 88–87 BC[40] | |||||||

| Emperor Zhao | Liu Fuling | 劉弗陵 | 30 March[35] 87 BC |

5 June[35] 74 BC[41] |

Emperor Xiaozhao | 孝昭皇帝 | Shiyuan | 始元 | 86–80 BC[42] |

| Yuanfeng | 元鳳 | 80–75 BC[42] | |||||||

| Yuanping | 元平 | 74 BC[42] | |||||||

| Marquis of Haihun | Liu He | 劉賀 | 18 July[35] 74 BC |

14 August[35] 74 BC[30] |

did not exist | Yuanping | 元平 | 74 BC[43] | |

| Emperor Xuan | Liu Bingyi | 劉病已 | 10 September[35] 74 BC |

10 Juanary[32] 49 BC[41] |

Emperor Xiaoxuan | 孝宣皇帝 | Benshi | 本始 | 73–70 BC[44] |

| Dijie | 地節 | 69–66 BC[44] | |||||||

| Yuankang | 元康 | 65–61 BC[44] | |||||||

| Shenjue | 神爵 | 61–58 BC[44] | |||||||

| Wufeng | 五鳳 | 57–54 BC[44] | |||||||

| Ganlu | 甘露 | 53–50 BC[44] | |||||||

| Huanglong | 黃龍 | 49 BC[44] | |||||||

| Emperor Yuan | Liu Shi | 劉奭 | 29 January[35] 49 BC |

8 July[45] 33 BC[46] |

Emperor Xiaoyuan | 孝元皇帝 | Chuyuan | 初元 | 48–44 BC[47] |

| Yongguang | 永光 | 43–39 BC[47] | |||||||

| Jianzhao | 建昭 | 38–34 BC[47] | |||||||

| Jingning | 竟寧 | 33 BC[47] | |||||||

| Emperor Cheng | Liu Ao | 劉驁 | 4 August[48] 33 BC |

17 April[49] 7 BC[46] |

Emperor Xiaocheng | 孝成皇帝 | Jianshi | 建始 | 32–28 BC[50] |

| Heping | 河平 | 28–25 BC[50] | |||||||

| Yangshuo | 陽朔 | 24–21 BC[50] | |||||||

| Hongjia | 鴻嘉 | 20–17 BC[50] | |||||||

| Yongshi | 永始 | 16–13 BC[50] | |||||||

| Yuanyan | 元延 | 12–9 BC[50] | |||||||

| Suihe | 綏和 | 8–7 BC[50] | |||||||

| Emperor Ai | Liu Xin | 劉欣 | 7 May[51] 7 BC |

15 August[49] 1 BC[46] |

Emperor Xiao'ai | 孝哀皇帝 | Jianping | 建平 | 6–3 BC[52] |

| Yuanshou | 元壽 | 2–1 BC[52] | |||||||

| Emperor Ping | Liu Kan | 劉衎 | 17 October[53] 1 BC |

3 February[54] 6 AD[46] |

Emperor Xiaoping | 孝平皇帝 | Yuanshi | 元始 | 1–5 AD[55] |

| Ruzi Ying[lower-alpha 3] | Liu Ying | 劉嬰 | 17 April[56] 6 AD |

10 January[56] 9 AD[46] |

did not exist | Jushe | 居攝 | 6–8 AD[57] | |

| Chushi | 初始 | 9 AD | |||||||

| Xin dynasty (9–23 AD) | |||||||||

| Continuation of Han dynasty | |||||||||

| Gengshi Emperor | Liu Xuan | 劉玄 | 11 March[58] 23 AD |

November[58] 25 AD[59] |

did not exist | Gengshi | 更始 | 23–25 AD[60] | |

| Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD) | |||||||||

| Emperor Guangwu | Liu Xiu | 劉秀 | 5 August[61] 25 AD |

29 March[62] 57 AD[63] |

Emperor Guangwu | 光武皇帝 | Jianwu | 建武 | 25–56 AD[64] |

| Jianwu- zhongyuan |

建武中元 | 56–57 AD[64] | |||||||

| Emperor Ming | Liu Zhuang | 劉莊 | 29 March[61] 57 AD |

5 September[62] 75 AD[65] |

Emperor Xiaoming | 孝明皇帝 | Yongping | 永平 | 57–75 AD[66] |

| Emperor Zhang | Liu Da | 劉炟 | 5 September[61] 75 AD |

9 April[62] 88 AD[67] |

Emperor Xiaozhang | 孝章皇帝 | Jianchu | 建初 | 76–84 AD[68] |

| Yuanhe | 元和 | 84–87 AD[68] | |||||||

| Zhanghe | 章和 | 87–88 AD[68] | |||||||

| Emperor He | Liu Zhao | 劉肇 | 9 April[61] 88 AD |

13 February[62] 106 AD[69] |

Emperor Xiaohe | 孝和皇帝 | Yongyuan | 永元 | 89–105 AD[70] |

| Yuanxing | 元興 | 105 AD[71] | |||||||

| Emperor Shang | Liu Long | 劉隆 | 13 February[61] 106 AD |

21 September[62] 106 AD[72] |

Emperor Xiaoshang | 孝殤皇帝 | Yanping | 延平 | 106 AD[73] |

| Emperor An | Liu Hu | 劉祜 | 23 September[61] 106 AD |

30 April[62] 125 AD[74] |

Emperor Xiao'an | 孝安皇帝 | Yǒngchū | 永初 | 107–113 AD[75] |

| Yuanchu | 元初 | 114–120 AD[75] | |||||||

| Yongning | 永寧 | 120–121 AD[75] | |||||||

| Jianguang | 建光 | 121–122 AD[75] | |||||||

| Yanguang | 延光 | 122–125 AD[75] | |||||||

| Marquess of Beixiang | Liu Yi | 劉懿 | 18 May[61] 125 AD |

10 December[62] 125 AD[76] |

did not exist | Yanguang | 延光 | 125 AD[77] | |

| Emperor Shun | Liu Bao | 劉保 | 16 December[61] 125 AD |

20 September[62] 144 AD[78] |

Emperor Xiaoshun | 孝順皇帝 | Yongjian | 永建 | 126–132 AD[79] |

| Yangjia | 陽嘉 | 132–135 AD[79] | |||||||

| Yonghe | 永和 | 136–141 AD[79] | |||||||

| Han'an | 漢安 | 142–144 AD[79] | |||||||

| Jiankang | 建康 | 144 AD[79] | |||||||

| Emperor Chong | Liu Bing | 劉炳 | 20 September[61] 144 AD |

15 February[62] 145 AD[80] |

Emperor Xiaochong | 孝沖皇帝 | Yongxi | 永熹 | 145 AD[81] |

| Emperor Zhi | Liu Zuan | 劉纘 | 6 March[61] 145 AD |

26 July[62] 146 AD[80] |

Emperor Xiaozhi | 孝質皇帝 | Benchu | 本初 | 146 AD[81] |

| Emperor Huan | Liu Zhi | 劉志 | 1 August[61] 146 AD |

25 January[62] 168 AD[82] |

Emperor Xiaohuan | 孝桓皇帝 | Jianhe | 建和 | 147–149 AD[83] |

| Heping | 和平 | 150 AD[83] | |||||||

| Yuanjia | 元嘉 | 151–153 AD[83] | |||||||

| Yongxing | 永興 | 153–154 AD[83] | |||||||

| Yongshou | 永壽 | 155–158 AD[83] | |||||||

| Yanxi | 延熹 | 158–167 AD[83] | |||||||

| Yongkang | 永康 | 167 AD[83] | |||||||

| Emperor Ling | Liu Hong | 劉宏 | 17 February[61] 168 AD |

13 May[62] 189 AD[84] |

Emperor Xiaoling | 孝靈皇帝 | Jianning | 建寧 | 168–172 AD[85] |

| Xiping | 熹平 | 172–178 AD[85] | |||||||

| Guanghe | 光和 | 178–184 AD[85] | |||||||

| Zhongping | 中平 | 184–189 AD[85] | |||||||

| Liu Bian | Liu Bian | 劉辯 | 15 May[61] 189 AD |

28 September[62] 189 AD[76] |

did not exist | Guangxi | 光熹 | 189 AD[86] | |

| Zhaoning | 昭寧 | 189 AD[86] | |||||||

| Emperor Xian | Liu Xie | 劉協 | 28 September[61] 189 AD |

11 December[lower-alpha 4] 220 AD[87] |

Emperor Xiaoxian | 孝獻皇帝 | Yonghan | 永漢 | 189 AD[88] |

| Chuping | 初平 | 190–193 AD[88] | |||||||

| Xingping | 興平 | 194–195 AD[88] | |||||||

| Jian'an | 建安 | 196–220 AD[88] | |||||||

| Yankang | 延康 | 220 AD[88] | |||||||

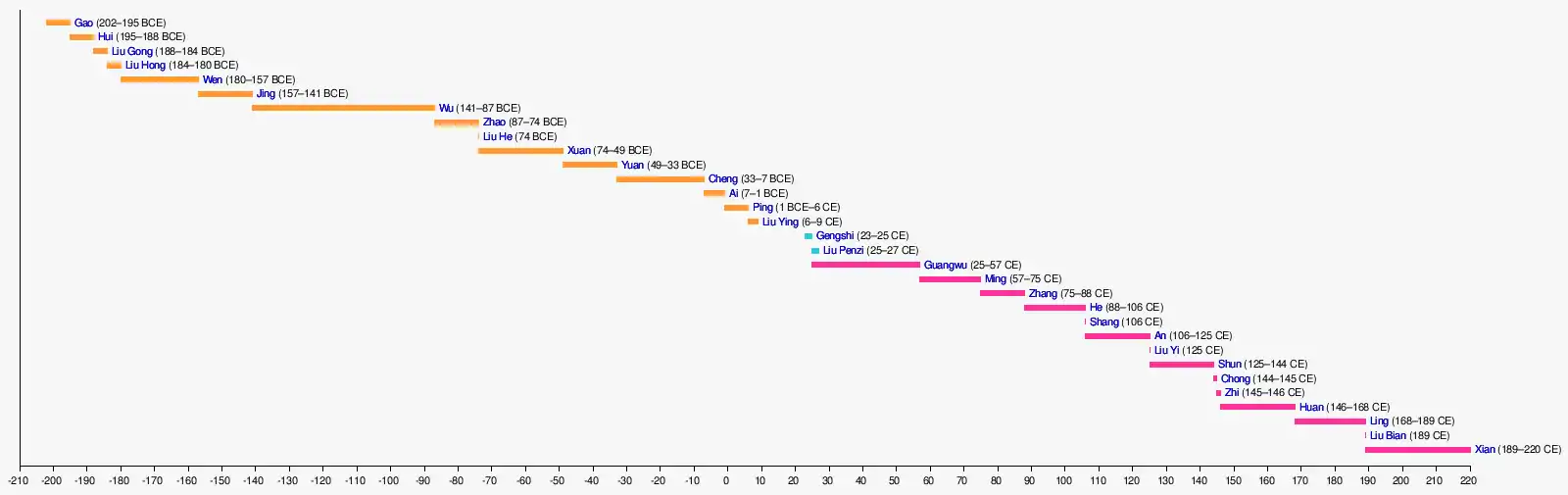

Timeline

Legend:

- Orange denotes Western Han monarchs

- Teal denotes Han monarchs following the collapse of the Xin dynasty but prior to the Eastern Han

- Pink denotes Eastern Han monarchs

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Besides Liu Bang and Liu Xiu, the word Xiao (孝 "filial") was prefixed to all posthumous names, although it is usually omitted by scholars. The word huangdi (皇帝 emperor) is also abbreviated. Commonly only the second character is used; e.g., Wudi (武帝, Emperor Wu) for Xiaowu Huangdi (孝武皇帝).[21]

- ↑ The years of the Chinese lunisolar calendar do not correspond exactly with the years given in the column for era names. Some years given in the table also belong to two reign periods because some era names were adopted before the beginning of the following year.

- ↑ Ruzi was prince, rather than emperor of Han. Officially, the throne of emperor of Han was vacant during 6 AD to 9 AD.

- ↑ de Crespigny, Rafe (2010). A Biography of Cao Cao 155-220 AD. Brill. p. 450. ISBN 978-90-04-18830-3.

On 11 December [...] Cao Cao's son and successor Cao Pi received the abdication of the last emperor of Han. [...] Some authorities give the date of abdication as 25 November [...] This is the date upon which Emperor Xian issued an edict acalling upon Cao Pi to take the throne, but the ceremonial transfer of sovereignty was carried out two weeks later

Citations

- ↑ Paludan 1998, pp. 34–36.

- ↑ de Crespigny 2006, p. 568.

- ↑ Hymes 2000, p. 36.

- ↑ Beck 1990, p. 21.

- ↑ Beck 1990, pp. 354–355.

- ↑ Hymes 2000, p. 16.

- ↑ de Crespigny 2006; Bielenstein 1980, p. 143; Hucker 1975, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Wang 1949, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Wang 1949, pp. 141–143; Ch'ü 1972, p. 71; de Crespigny 2006, pp. 1216–1217.

- ↑ de Visser 2003, pp. 43–49.

- 1 2 Wilkinson 1998, p. 105.

- ↑ Wilkinson 1998, pp. 105–106.

- 1 2 Wilkinson 1998, p. 106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wilkinson 1998.

- 1 2 3 Wilkinson 1998, p. 177; Sato 1991, p. 278.

- 1 2 Wilkinson 1998, p. 177; Sato 1991, pp. 278–279.

- 1 2 Wilkinson 1998, p. 178.

- ↑ Loewe & Twitchett 1986, p. 135; Hansen 2000, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Loewe & Twitchett 1986, pp. 136–137; Torday 1997, p. 78.

- ↑ Loewe & Twitchett 1986, pp. 174–187; Huang 1988, p. 44–46.

- ↑ Dubs 1945, p. 29.

- ↑ Barbieri-Low & Yates 2015, pp. xix–xx; Hulsewé 1995, pp. 226–230.

- ↑ Grand Scribe's Records, p. 108.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range come from Paludan (1998), p. 28

- 1 2 3 4 Bo Yang 1977, pp. 433–443.

- 1 2 3 Barbieri-Low & Yates 2015, pp. xix–xx; Hulsewé 1995, pp. 226–230; Vervoorn 1990, pp. 311–312.

- 1 2 Grand Scribe's Records, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range come from Paludan (1998), p. 28, 31

- 1 2 Grand Scribe's Records, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range come from Loewe & Twitchett (1986), p. xxxix

- ↑ Grand Scribe's Records, pp. 136.

- 1 2 Vervoorn 1990, p. 312.

- 1 2 Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range come from Paludan (1998), 28, 33.

- 1 2 Bo Yang (1977), 444–447.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Barbieri-Low & Yates 2015, pp. xix–xx; Vervoorn 1990, p. 312.

- ↑ Grand Scribe's Records, p. 213.

- 1 2 3 Bo Yang (1977), 447–452.

- ↑ Hymes 2000, p. 11; Hulsewé 1995, pp. 226–230.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range come from Paludan (1998), 28, 36 and Loewe (2000), 273–280.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Bo Yang (1977), 452–471.

- 1 2 Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range come from Paludan (1998), 40.

- 1 2 3 Bo Yang (1977), 471–473.

- ↑ Bo Yang (1977), 473.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bo Yang (1977), 473–480.

- ↑ Loewe & Twitchett 1986, p. 225.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 40, 42.

- 1 2 3 4 Bo Yang (1977), 481–484.

- ↑ Loewe & Twitchett 1986, p. 225; Vervoorn 1990, p. 313; Barbieri-Low & Yates 2015, pp. xx.

- 1 2 Loewe & Twitchett 1986, p. 227; Vervoorn 1990, p. 313.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bo Yang (1977), 485–489.

- ↑ Barbieri-Low & Yates 2015, pp. xx; Vervoorn 1990, p. 312.

- 1 2 Bo Yang (1977), 490.

- ↑ Barbieri-Low & Yates 2015, pp. xx; Hymes 2000, p. 12; Vervoorn 1990, p. 313.

- ↑ Hymes 2000, p. 13; Vervoorn 1990, p. 313.

- ↑ Bo Yang (1977), 495. While traditional sources do not give an exact date when the Yuanshi era was announced, it was implied that the first year of Yuanshi did not start until the first month of the lunar calendar — ergo, in 1 AD. See, e.g., Ban Gu, Book of Han, vol. 12.

- 1 2 Loewe & Twitchett 1986, p. 231; Vervoorn 1990, p. 313.

- ↑ Bo Yang (1977), 495–496.

- 1 2 Loewe & Twitchett 1986, pp. 246–251; Vervoorn 1990, p. 313.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from de Crespigny (2007), 558–560.

- ↑ Bo Yang (1977) 500–501.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Barbieri-Low & Yates 2015, pp. xx; de Crespigny 2006, p. xxxiii; Loewe & Twitchett 1986, pp. xl–xli.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Loewe & Twitchett 1986, pp. xl–xli; de Crespigny 2006, p. xxxiii.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 44 and de Crespigny (2006), 557–566.

- 1 2 Bo Yang (1977), 501–509.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 44, 49 and de Crespigny (2007), 604–609.

- ↑ Bo Yang (1977), 509–513.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 44, 49 and de Crespigny (2007), 495–500.

- 1 2 3 Bo Yang (1977), 514–516.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 50 and de Crespigny (2007), 588–592.

- ↑ Bo Yang (1977), 517–523.

- ↑ Bo Yang (1977), 523.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 50 and de Crespigny (2007), 531.

- ↑ Bo Yang (1977), 524.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 50 and de Crespigny (2007), 580–583.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bo Yang (1977), 524–529.

- 1 2 Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Twitchett and Loewe (1986), xl.

- ↑ Bo Yang (1977), 529.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 50–51 and de Crespigny (2007), 473–478.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bo Yang (1977), 530–534.

- 1 2 Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 50–51.

- 1 2 Bo Yang (1977), 535.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 50–51 and de Crespigny (2007), 595–603

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bo Yang (1977), 535–541.

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 50, 52 and de Crespigny (2007), 511–517.

- 1 2 3 4 Bo Yang (1977), 541–547.

- 1 2 Bo Yang (1977), 547

- ↑ Latin spelling, Chinese characters, and date range from Paludan (1998), 50, 55.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bo Yang (1977), 547–564.

Sources

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony J.; Yates, Robin D.S. (2015). "Recognized Rulers of the Qin and Han Dynasties and the Xin Period". Law, State, and Society in Early Imperial China. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-30053-8.

- Beck, B. J. Mansvelt (1990). The Treatises of Later Han: Their Author, Sources, Contents, and Place in Chinese Historiography. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-08895-5.

- Bielenstein, Hans (1980). The Bureaucracy of Han Times. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22510-6.

- Bo Yang (1977). 中國歷史年表 [Timeline of Chinese History]. Sing-Kuang Book Company Ltd.

- Ch'ü, T'ung-tsu (1972). Han Dynasty China: Volume 1: Han Social Structure. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95068-6.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2006). "Chronology Part II: Later Han". A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- Dubs, Homer H. (1945). "Chinese Imperial Designations". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 65 (1): 26–33. doi:10.2307/594743. JSTOR 594743.

- Hulsewé, Anthony François Paulus (1995). Remnants of Han Law. Sinica Leidensia, ed. Institutum Sinologicum Lugduno Batavum, Vol 9. Brill Publishers. pp. 226–230.

- Hansen, Valerie (2000). The Open Empire: A History of China to 1600. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-97374-7.

- Huang, Ray (1988). China: A Macro History. Armonk & London: M.E. Sharpe Inc., an East Gate Book. ISBN 978-0-87332-452-6.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1975). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0887-6.

- Hymes, Robert (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11004-4..

- Loewe, Michael; Twitchett, Denis, eds. (1986). The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Loewe, Michael (2000). A Biographical Dictionary of the Qin, Former Han, and Xin Periods (221 BC - AD 24). Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10364-1.

- Paludan, Ann. (1998). Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: the Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05090-3.

- Sato, Masayuki (1991). "Comparative Ideas of Chronology". History and Theory. 30 (2): 275–301. doi:10.2307/2505559. JSTOR 2505559.

- Torday, Laszlo (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: Durham Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- Vervoorn, Aat Emile (1990). "Chronology of Dynasties and Reign Periods". Men of the Cliffs and Caves. Chinese University Press. ISBN 978-962-201-415-2.

- de Visser, M.W. (2003). Dragon in China and Japan. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-5839-9.

- Wang, Yu-ch'uan (1949). "An Outline of the Central Government of the Former Han Dynasty". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 12 (1/2): 134–187. doi:10.2307/2718206. JSTOR 2718206.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (1998). Chinese History: A Manual. Harvard University Asia Center of the Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-12378-6.

- Sima, Qian (1994) [c. 91 BC]. The Grand Scribe's Records. Vol. 2. Translated by W.H. Nienhauser; W. Cao; Scott W. Galer; W.H. Nienhauser; D.W. Pankenier. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34022-1.

External links

- Chinese History - Han Dynasty 漢 (206 BC-8 AD, 25–220) emperors and rulers, from Chinaknowledge.de

Media related to Han Dynasty at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Han Dynasty at Wikimedia Commons