The following is a list of riots and protests involving violent disorder that have occurred in London:

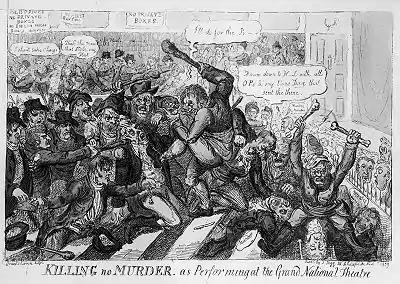

Cartoon of the Old Price Riots, 1809, following a rise in the price of theatre tickets

- 1189: The Massacre of the Jews at the coronation of Richard I

- 1196: William with the long beard causes riots when he preaches for the poor against the rich

- 1221: Riots occur after London defeats Westminster in an annual wrestling contest; ring-leaders hanged or mutilated in punishment.[1][2]

- 1268: Rioting between goldsmiths and tailors[2][3]

- 1340: Fishmongers riot with Skinners after a Skinner murders a Fishmonger's servant, Ralph Turk.[4]

A dispute arose between certain of the craft of the goldsmiths and certain of the craft of the tailors

The Justiciar...took proceedings against them in the King's behalf, saying that they, against the peace and their fealty to his lordship the King, had gone armed in the City, and had at night wickedly and feloniously wounded some persons, and had slain others, whose bodies, it was said, had been thrown into the Thames.

- 1391: Riots break out in Salisbury Place over a baker's loaf[2]

- 1517: Evil May Day riot against foreigners takes place

- 1668: Bawdy House Riots took place following repression of a series of attacks against brothels[5]

- 1710: Sacheverell riots, following the trial of the preacher, Henry Sacheverell

- 1719: Spitalfields weavers rioted, attacking women wearing Indian clothing and then attempting to rescue their arrested comrades[6]

- 1743: Riots against Gin Taxes and other legislation to control the Gin Craze, principally the Gin Act 1736; rioting was fuelled by consumption of the drink itself[7]

- 1768: The Massacre of St George's Fields after the imprisonment of John Wilkes for criticising the King

- 1769: The Spitalfield riots when silk weavers attempted to maintain their rate of pay

- 1780: Gordon riots against Catholics

- 1788: The notorious Westminster by-election held in the summer of 1788 resulting in 2 deaths and more than 40 injured.[8]

- 1809: Old Price Riots, 1809 following a rise in the price of theatre tickets

- 1816: Spa Fields riots, Spenceans met in support of the common ownership of land

- 1830: Attacks against the Duke of Wellington in his carriage and on his home, for his opposition to electoral reform (which had been seen partly as a solution to rioting by rural workers).

- 1866: a riot took place in Hyde Park after a meeting of the Reform League was declared illegal

- 1886: The West End Riots followed a counter-demonstration by the Social Democratic Federation against a meeting of the Fair Trade League.[9]

- 1887: Bloody Sunday, a demonstration against coercion in Ireland and to demand the release from prison the MP William O'Brien

- 1907: The Brown Dog riots, medical students attempt to tear down an anti-vivisection statue.

- 1919: The Battle of Bow Street, Australian, American and Canadian servicemen rioted against the Metropolitan Police

- 1932: The National Hunger March ended in rioting after the police confiscated the petition of the National Unemployed Workers' Movement

Red commemorative plaque in Dock Street

- 1936: The Battle of Cable Street saw rioting against the Metropolitan Police as they attempted to facilitate a march by the British Union of Fascists

- 1958: Notting Hill race riots between White British and West Indian immigrants.

- 1968: Rioting outside the United States Embassy in Grosvenor Square in opposition to the Vietnam War.

- 1974: Red Lion Square disorders happened following a march by counter-fascists against the National Front.

- 1976: Riots during the Notting Hill Carnival.

- 1977: The Battle of Lewisham occurred when the Metropolitan Police attempted to facilitate a march by the National Front[10]

- 1979: Southall riots during an Anti-Nazi League demonstration in opposition to the National Front.

- 1981: Brixton riot against the Metropolitan Police. Especially on 10 July, rioting extended to other parts of London and numerous other cities around the UK[11]

- 1985: Brixton riot against the Metropolitan Police after they shot the mother of suspect Michael Groce

- 1985: Broadwater Farm riot, residents of Tottenham riot against the Metropolitan Police following a death during a police search

- 1990: Poll Tax riots followed the introduction of a poll tax

- 1993: Welling riots, October 1993.[12] A march organised by the ANL,[13][14] the SWP and Militant resulted in riots against the Metropolitan police.[12][note 1]

- 1994: Riot during the second march against the Criminal Justice Bill

- 1995: 1995 Brixton riot against the Metropolitan Police occurred after a death in police custody

- 1996: Rioting in Trafalgar Square and surrounding streets following England losing against Germany in the semi-final of UEFA Euro 1996

Police push back rioters during the 2011 London riots

- 1999: Carnival Against Capitalism riot

- 2000: Anti-capitalist May Day riot[17]

- 2001: May Day riot in central London by anti-capitalist protestors.[18]

- 2002: Rioting around The New Den stadium following Millwall F.C. losing against Birmingham City F.C. in the 2002 Football League Division One play-off.

- 2009: G-20 London summit protests occurred in the days around the G-20 summit.

- 2009: Upton Park riot before, during and after a 2009–10 Football League Cup second round match between West Ham United F.C. and Millwall F.C.

- 2010: UK student protests against increases in student fees and public sector cuts.

- 2011: Anti-cuts protest in London against government public spending cuts.

- 2011: England riots, initially in London, following the police shooting of Mark Duggan in Tottenham

- 2017: Rioting outside Forest Gate police station following the Death of Edson Da Costa.

References

- ↑ Palmer, Alan; Palmer, Veronica (1992). The Chronology of British History. London: Century Ltd. pp. 79–81. ISBN 0-7126-5616-2.

- 1 2 3 "John Strype's Survey of London Online". hrionline.ac.uk. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ "Introduction". British History Online. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Barbara A. Hanawalt (1998). Of Good and Ill Repute: Gender and Social Control in Medieval England. ISBN 9780195109498.

- ↑ "Striking the posture of a whore: the Bawdy House Riots and the "antitheatrical prejudice". – Free Online Library". thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ "'Industries: Silk-weaving', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 2". british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ "The Gin Craze and Gin Riots". staticandwine.blogspot.com. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ "Westimnster by election riot of 1788". thehistoryofparliament.wordpress.com. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ↑ "Marxism and Rioting". whatnextjournal.co.uk. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ "BBC ON THIS DAY – 13 – 1977: Violent clashes at NF march". BBC. 13 August 1977. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ "A Different Reality: minority struggle in British cities". University of Warwick. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- 1 2 DK Renton. "Memories of Welling". DKRenton.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- 1 2 Dearlove, John (2000). Introduction to British politics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7456-2096-1.

- 1 2 3 "Welling: Disturbances". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 18 October 1993. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ↑ Moyes, Jojo (15 November 1993). "Hard-left violence 'hurting anti-racist organisations'". The Independent. London. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- ↑ Saggar, Shamit (1998). Race and British electoral politics. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-85728-830-8.

- ↑ "BBC ON THIS DAY – 1 – 2000: May Day violence on London streets". BBC. 1 May 2000. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ "The London May Day protests at a glance". The Guardian. 1 May 2001. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

Notes

- ↑ The march was against the headquarters of the British National Party, located in the area.[13] Thousands of people attended the demonstration, for which 2,600 police officers were deployed.[14] A hardcore element associated with the SWP and Militant[15] refused to accept police instruction to divert the march away from the BNP's headquarters itself, once it had gone past it. In a resulting riot, 21 police officers and 41 demonstrators were injured.[14] In 1995, Welling Council shut down the BNP headquarters.[16]

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.