Litwa (transl. Lithuania) was a Polish-language newspaper edited and published by Mečislovas Davainis-Silvestraitis in Vilnius, then part of the Russian Empire, from July 1908 to May 1914.

It was published monthly in 1908, every two weeks in 1909–1912, and weekly in 1913–1914. The newspaper was mainly directed to the Polish-speaking Lithuanian nobles who maintained the dual Polish-Lithuanian identity and sought to involve them in the Lithuanian National Revival.[1] Lithuanian activists believed that the nobles were Lithuanians who "forgot" their Lithuanian roots and heritage and needed to be "returned" to the Lithuanian nation.[2] The newspaper supported the concept of the ethnographic Lithuania and fiercely criticized ideas about recreating the old Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by the Polish National Democracy.[3] More practically, Litwa also wrote on how to address the Polonization of Vilnius and Vilna Governorate. This later led to the establishment of a separate Polish-language magazine Lud targeting the Polish-speaking peasants living in the area. The newspaper did not become a catalyst for polemic discussions and did not generate any new ideas. It mainly translated and reflected ideas propagated by the Lithuanian Christian Democrats and Nationalist Democrats.[4] It failed to attract and retain interest of Polish groups, the Krajowcy, or activists of the Belarusian National Revival. The newspaper was discontinued due to low readership and financial difficulties in May 1914.

Publication history

Plans for the newspaper were made in 1905. Mečislovas Davainis-Silvestraitis and Jonas Basanavičius discussed establishing the newspaper in March 1905 and Davainis-Silvestraitis drafted its program in November 1905.[5] Davainis-Silvestraitis and Donatas Malinauskas published their proposal for a new newspaper that would "soften" the Lithuanian–Polish relations in Kurjer Litewski in January 1907, but actual work on establishing the publication began only in 1908. Together with Basanavičius, Davainis-Silvestraitis completed the newspaper's project in May 1908, obtained government permit, and published the first issue on 24 July 1908.[6] It was published monthly in 1908, every two weeks in 1909–1912, and weekly in 1913–1914.[7]

The initial issue had a circulation of 2,000 copies but was quickly reduced to 1,000 copies. Even then, Davainis-Silvestraitis managed to sell only some 60–70% of the run in 1909.[8] The initial issue had only 47 subscribers but the number of subscribers grew to 476 in 1909 and 631 in 1911–1913.[9] Despite targeting Lithuanian nobles, the newspaper was subscribed mainly by the Catholic clergy (out of 476 subscribers in 1909, 315 were priests and only 51 were nobles).[10] The newspaper was also distributed via various bookstores, Lithuanian societies, and other Lithuanian periodicals. Davainis-Silvestraitis sent copies of Litwa to several Polish, Belarusian, Latvian, and Ukrainian periodicals.[11] Low circulation brought financial difficulties. In 1910, Šaltinis and Lietuvos ūkininkas published public appeals to send financial support to Litwa. In 1913, the newspaper was near bankruptcy and asked Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas for help. However, only small sums were collected and the newspaper was discontinued in May 1914.[12]

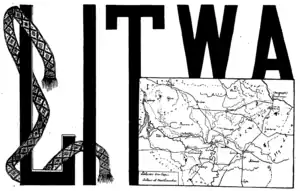

Nameplates

Litwa used different nameplates each year.[13] The nameplate of the first issue effectively defined which Lithuania it would write about – it included a traditional folk sash wrapping around the letter L[13] and a map of ethnographic Lithuania and not of historic Lithuania (i.e. the Grand Duchy of Lithuania).[14] The map was prepared and first published by Mečislovas Vasiliauskas in 1907.[15]

Particularly artistic was the nameplate used in 1911–1912. It is an allegoric drawing by Władysław Leszczyński which depicts a raising sun (symbol of hope for the future), two peasants reading Litwa and Viltis, and a reaper looking in awe at the ruins that spell out Litwa and the coat of arms of Lithuania (a reference to the historic Grand Duchy of Lithuania).[16] The nameplate also featured other symbols of peasant life – a column shrine, nesting storks, rich vegetation.[13]

Content

Litwa published numerous articles that modern Lithuania needs to be based on ethnographic principles (i.e. the concept of ethnographic Lithuania) and not on the historic traditions of the old Grand Duchy.[14] It did not formulate new ideas, but translated and reflected ideas propagated by the Lithuanian Christian Democrats and National Democrats.[14] For example, while Litwa repeated ideas about the ethnographic Lithuania but did not try to work out which specific territories would be included or excluded.[17] Litwa more actively attempted to explain and substantiate Lithuanian national aspirations to Vilnius and Vilna Governorate even though the areas had very little of Lithuanian-speaking population (see demographic history of the Vilnius region). They used the ethnographic arguments, i.e. that the population in these areas were ethnically Lithuanian even though they have forgotten their roots.[18]

It also offered no new ideas, arguments, or approaches to its main goal of enticing the nobles to join the National Revival. Its main ideas were already discussed in Aušra and Varpas.[19] There was little guidance on how the nobles could join the National Revival. Firstly, they needed to support political aspirations of Lithuanians and reject ideas of the Polish National Democracy (Endecja) about recreating the old Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. But then there was no agreement whether the nobility needed to abandon the Polish language and fully switch to Lithuanian (Davainis-Silvestraitis was more moderate on the issue and did not consider it necessary).[3] In addition, Litwa advocated for a "democratic" intelligentsia, i.e. where nobles and peasants were treated as equal, and elimination of old social class prejudices. For example, it supported marriages between nobles and peasants.[20]

Litwa attempted to explain how Lithuanians became Polonized and to rethink and reevaluate the history of Lithuania, and in particular the Union of Krewo (1385) and the Union of Lublin (1569) that created a union between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland. The newspaper attempted to rebuke Polish claims that the unions brought western civilization to "barbaric" Lithuania and condemned Polonization of Lithuania which "robbed" Lithuanians of their language, culture, traditions, and identity.[21] It further denied that Lithuania was ever a province of Poland and rejected the Kresy myth.[22] At the same time, the newspaper did not criticize various Russification policies implemented by the Russian Empire even causing baseless rumors that the newspaper was funded by the government.[23]

In addition to polemic articles, the newspaper published some literary works, particularly poems. Stefanija Jablonskienė (Stefania Jabłońska) published a few Lithuanian poems translated to Polish, including excerpts from The Forest of Anykščiai by Antanas Baranauskas, poems by Maironis, Adomas Jakštas, Liudas Gira.[24] She also translated Tautiška giesmė (which later became the national anthem of Lithuania) by Vincas Kudirka. It was the first translation of the poem into Polish, and it was published twice as poetic and word-by-word translations.[13]

Lud

Litwa had a more detailed program on how to address Polonization of Vilnius and Vilna Governorate.[25] This later led to the establishment of a separate Polish-language magazine Lud in January 1912 (it was discontinued in early 1913). The project was proposed in Lietuvos žinios, supported by the members of the Lithuanian Democratic Party, and entrusted to Davainis-Silvestraitis to edit and publish.[25] Its primary goal was to encourage "Polonized" peasants to "return" to their Lithuanian roots and it mainly published articles about the use of Polish language in Catholic churches and attempts to introduce Lithuanian-language masses and services.[25] Such efforts dated back to the struggle of the Twelve Apostles of Vilnius to obtain the Church of Saint Nicholas for the Lithuanian community in Vilnius. Lud was more didactic and forceful on the language issue; it argued that those who abandon their native language reject God, their parents and ancestors, and their homeland.[26] Another newspaper aimed at Belarusianized Lithuanians (i.e. those speaking Belarusian) was proposed by priest Jonas Žilius-Jonila in 1909 but the project did not receive much support.[27]

Relationship to other groups

.png.webp)

Initially, there were hopes that the newspaper would become a neutral place for the Lithuanian–Polish debate and would foster an understanding between the two nations.[29] However, it quickly became apparent that the newspaper would advocate the Lithuanian positions. As a result, it was harshly criticized in the Polish press, particularly in Kurier Wileński, Gazeta Codzienna, Dziennik Petersburski and other periodicals published by the Polish National Democracy (Endecja). They did not consider the newspaper and its articles worthy of serious discussion and treated them as silly declarations.[30]

Litwa hoped to attract the Krajowcy, a group of intellectuals who attempted to maintain their dual self-identification as Polish–Lithuanian, specifically historian Konstancja Skirmuntt, attorney Michał Pius Römer, noblemen Ignacy Karol Milewski and Tadeusz Wróblewski.[31] The newspaper published selected texts by these authors, but their ideas became increasingly edited or rejected.[32]

Litwa and Davainis-Silvestraitis considered Catholics who spoke Belarusian and lived in Vilna Governorate to be ethnic Lithuanians who "forgot" their roots and who needed to be "returned" to the Lithuanian nation.[33] However, Belarusians were viewed more as potential allies than a threat.[34] Additionally, Davainis-Silvestraitis maintained contacts with Belarusian activists Anton Luckievich, Vaclau Lastouski, and Yanka Kupala.[35] Therefore, on a few occasions, the newspaper supported the emerging Belarusian National Revival when it could be used against the Poles.[36] Litwa had a section on the Belarusian press and republished a few articles from Nasha Niva. More substantial contribution included a lengthy history of the Belarusian National Revival by Luckievich and an article about the Battle of Grunwald by Lastouski published in 1909.[37] However, Lithuanian activists soon realized that Belarusians would also claim the heritage of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and develop the concept of ethnographic Belarus that would considerably overlap with the Lithuanian visions of ethnographic Lithuania.[38] This realization turned Litwa against the Belarusians.[39]

Other Lithuanian activists thought the newspaper was either too anti-Polish or not Lithuanian enough. When it became clear that the newspaper would be discontinued due to financial troubles, Mykolas Sleževičius and Kazys Grinius published articles in Lietuvos žinios criticizing Litwa for its harsh anti-Polish stance which, they claimed, alienated the intended audience (i.e. the nobles) and proposed that a new Polish-language newspaper which would focus on economic and trade issues.[40] Their opinion is supported by a diary of a young noble who went from supporting the newspaper (because it was the only Lithuanian newspaper in Polish) to calling it an "absolute shit" (gówno gównem) in the span of three months.[41] But when the newspaper was not insistent that the nobles needed to adopt the Lithuanian language, Litwa and Davainis-Silvestraitis were criticized by Gabrielius Landsbergis-Žemkalnis and Kazimieras Prapuolenis even suggested replacing Davainis-Silvestraitis with a more "reliable" editor.[42] Such criticism was hurtful and Davainis-Silvestraitis felt misunderstood and unappreciated. Feeling rejected by the younger generation of Lithuanian activists, Davainis-Silvestraitis slowly retreated from the Lithuanian cultural life.[43]

Contributors

Litwa had only a few active contributors. Researcher Olga Mastianica identified Gabrielius Landsbergis-Žemkalnis, Adomas Jakštas, Kazimieras Prapuolenis, Kazimieras Pakalniškis, Liudas Gira, Jonas Basanavičius, Helena Cepryńska, Otton Zawisza, Stefania Wojniłowiczowa, and Stefanija Jablonskienė (Stefania Jabłońska) as the most active authors.[44] A few articles were published by Mykolas Biržiška, Petras Klimas, Martynas Yčas, Stanislovas Didžiulis, Juozas Ambraziejus, and others. However, frequently these were translations and republications of articles previously published in Lithuanian periodicals such as Viltis, Šaltinis, Draugija. Most of the original and ideological articles were written by Davainis-Silvestraitis.[44]

References

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 10, 109.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 18.

- 1 2 Mastianica 2016, pp. 114–116.

- ↑ Sniečkutė 2017, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 94.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 96.

- ↑ Serapinas 2021.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 99.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 100.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 101.

- 1 2 3 4 Girininkienė 2014.

- 1 2 3 Mastianica 2016, p. 104.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 105.

- ↑ Girininkaitė 2017b, p. 364.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 107.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 109.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 104–106.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 136.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Mastianica-Stankevič 2020, p. 60.

- 1 2 3 Mastianica 2016, p. 121.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 150–151.

- ↑ Vaskelaitė 2020, p. 79.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 134.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 143–147.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 149.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 156.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 151, 154.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 151.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 158–160.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, p. 167.

- ↑ Girininkaitė 2017a, pp. 384–385.

- ↑ Mastianica 2016, pp. 167–170.

- ↑ Mastianica-Stankevič 2020, pp. 62–63, 71.

- 1 2 Mastianica 2016, p. 97.

Bibliography

- Girininkienė, Vida (1 August 2014). "Pamiršti eilėraščiai Vincui Kudirkai ir Pranui Vaičaičiui". Literatūra ir menas (in Lithuanian). 31 (3485). ISSN 0233-3260.

- Girininkaitė, Veronika (2017a). "Laikraštis Litwa prenumeratoriaus akimis". Archivum Lithuanicum (in Lithuanian). 19. ISSN 1392-737X.

- Girininkaitė, Veronika (2017b). "Olga Mastianica. Bajorija lietuvių tautiniame projekte (XIX a. pabaiga–XX a. pradžia)". Archivum Lithuanicum (in Lithuanian). 19. ISSN 1392-737X.

- Mastianica, Olga (2016). Bajorija lietuvių tautiniame projekte (XIX a. pabaiga – XX a. pradžia) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas. ISBN 978-609-8183-13-9.

- Mastianica-Stankevič, Olga (2020). "Mečislovas Davainis-Silvestraitis ir jo Dienoraštis" (PDF). In Mastianica-Stankevič, Olga; Venckienė, Jurgita (eds.). Dienoraštis 1904–1912 (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos istorijos institutas. ISBN 978-609-8183-76-4.

- Serapinas, Valdemaras, ed. (14 April 2021) [2018]. ""Litwa"". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras.

- Sniečkutė, Marija (2017). "Olga Mastianica, Bajorija lietuvių tautiniame projekte (XIX a. pabaiga – XX a. pradžia), Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2016. 200 p. ISBN 978-609-8183-13-9". Lithuanian Historical Studies. 21. ISSN 1392-2343.

- Vaskelaitė, Vilma (2020). "Lietuvystės Samsonas pakirptais plaukais" (PDF). Naujasis Židinys - Aidai (in Lithuanian). 7. ISSN 1392-6845.