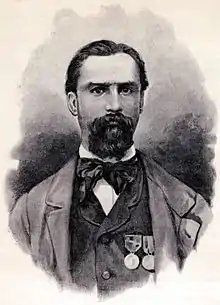

Livio Zambeccari | |

|---|---|

1892 | |

| Born | Tito Livio Zambeccari 30 June 1802 |

| Died | 2 December 1862 |

| Alma mater | "Collegio San Luigi" (Bologna) University of Bologna |

| Occupation(s) | risorgimento activist Liberation fighter Liberation journalist |

| Parents |

|

Livio Zambeccari (30 June 1802 - 2 December 1862) was a risorgimento activist and, for his admirers, hero. He was involved, sometimes on the frontline, in various liberation wars and skirmishes that marked the Italian struggle for independence between 1821 and 1860. He was, through much of his life, frequently forced into exile by the authorities. Between 1826 and 1840 he was active on the side of liberalism and nationalism in South America where he participated in several major wars. Zambeccari's courage and commitment to the liberation cause were beyond doubt, but among more thoughtful comrades he nevertheless suffered from a reputation as an outspoken and impulsive buffoon. Felice Orsini wrote: "Zambeccari is a very close friend, but be in no doubt that when danger threatens, in those situations where military insight and resolve are needed, it is unfortunately the case that he is useless. That is a great pity, because the man is devoted to his country."[1][2][lower-alpha 1]

In the 2003 Brazilian television series "A Casa das Sete Mulheres "("At the home of seven women") the part of Livio Zambeccari is played by Ângelo Antônio.[3]

Biography

Provenance and early years

Tito Livio Zambeccari was born, like his father before him, in Bologna, which since 1797 had been part of the Cisalpine Republic, a "sister republic" (through conquest) of the French Republic. He was his parents' only son, and the second of their three children.[4] Count Francesco Zambeccari (1752-1812), his father, a polymath-scientist and naval officer, was well known as an aviation pioneer.[1][4][5] Livio Zambeccari was just ten when, on 21 September 1812, a balloon that his father was piloting caught fire, following a collision with a tree during take-off. The alcohol powering the burner spilt onto the two occupants of the aircraft, as a result of which they were very badly burned. Francesco Zambeccari died the next day as a result of his injuries.[6] Francesco Zambeccari had nevertheless lived for long enough to exercise a considerable influence on Livio, whose own life would reflect his father's "man of action" propensities.[1]

A year after his father's death he was enrolled at Bologna's venerable "Collegio San Luigi" (secondary school).[4] By the time he had completed his schooling both his parents were dead, and in 1818 he entered the local university to study first Philosophy and then, in compliance with the wishes of the relatives who had taken on responsibility for his care, Jurisprudence. He graduated with an excellent law degree in 1821,[4] but instead of embarking on the career as a diplomat which had been intended for him, he now became involved with liberals and joined the Freemasons. He allowed himself to be drawn into "obscure missions" which compromised him politically, and as a result he was obliged to emigrate.[1]

Long exile: 1821-1840

The initial part of what turned out to be a long period of exile was spent in Spain where he served under Generals Antonio Quiroga and Rafael del Riego who were leading and sustaining a three-year military uprising against the authoritarian rule of King Ferdinand VII.[7] His initial period of service was relatively brief, but he re-joined the revolutionary armies in 1822 after news came through of an imminent French invasion designed to put an end to not quite three years of relatively liberal government in Spain. The king of France succeeded in returning Spain to a form of pre-revolutionary autocratic governance. With the "liberal experiment" terminated, Zambeccari spent three years between travelling in Europe and indulging a passion for scientific enquiry which he had inherited from his father. Although the range of his scientific interests can be characterised as eclectic, his travels involved a particular focus on Mineralogy.[1][8]

In 1823 he headed for England where he undertook a lengthy stay in London. That was followed by an equivalent stay in Paris. There is no indication of any attempt to return to Italy at this point. In 1826, like many exiled Italian patriots, he headed for South America, arriving in Montevideo later that same year. He arrived in the middle of an independence war between the Cisplatina province and the newly launched "Empire of Brazil". Cisplatina (which would be rebranded as Uruguay after winning independence in 1828) was already home to large numbers of Italian political exiles. Supported by his Masonic connections and the reputation among Italian patriots that he had already acquired through his activism in Europe, he rapidly found himself part of an expatriate Italian network. His arrival was greeted with enthusiasm by senior leaders of the Cisplatinan revolutionaries fighters such as Generals Juan Antonio Lavalleja and Manuel Oribe who invited him to take command of the revolutionary army's artillery: this was one invitation he felt able to refuse.[2] He instead devoted his energies to his scientific and literary studies while remaining in close contact with liberationist military circles.[1][9] One practical outcome of his literary studies was his rapidly-acquired mastery of the Spanish language to a level which very soon enabled him to embark on a parallel career as a "liberation journalist".[10]

After turning down the opportunity to organise the artillery for the Uruguay liberation forces, Zambeccari relocated across the Plata estuary to Buenos Aires.[2] At once, through his pen, he provided support for the liberationist cause, publishing an adaptation of Bruto Primo by Vittorio Alfieri,[lower-alpha 2] and also publishing a "Hymn to Liberty" ("Inno alla libertà") of his own as a fundraiser for the wounded heroes of Ituzaingó, the battle whereby the Cisplatina province effectively secured independence from the Empire of Brazil (though that was an outcome only formally secured, following British mediation / encouragement, eighteen months later through the Treaty of Montevideo, the founding treaty of the independent state of Uruguay).[1]

Following Zambeccari's arrival in Buenos Aires, he at once found himself caught up in the internal fighting between liberal "unitarians" and the more conservative "federalists": he was drawn towards the former. Lined up alongside Juan Antonio Lavalleja, he participated in several important military successes. That was not enough to prevent the federalists, under the leadership of Caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas, from regrouping and inflicting a severe defeat on the armies of the unitarians during the first part of 1829.[12][13]

Later in 1829 Caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas took power as governor in Buenos Aires, marking the start of what de Rosas characterised as a three-year benevolent dictatorship, and opponents viewed in less charitable terms. Zambeccari left the country, moving now to Porto Alegre in the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul, where he became involved with another liberation movement, backing the separatist "rebel monarchist" Bento Gonçalves da Silva. During the next few years he switched roles frequently, at times a liberation journalist, sometimes a scientific researcher, and at other times working as a private secretary to Gonçalves. According to one commentator, he emerged "as one of the inspirers and theorists of the republican revolution"[lower-alpha 3] Among the other leading companions of Gonçalves during the years of what many English language sources term the "Ragamuffin War", for students of Italian unification the most famous was another of the Italian patriot exiles, Giuseppe Garibaldi. It may have been Zambeccari who first introduced Garibaldi to Gonçalves. It was, in any event, during 1834/35 that Garibaldi arrived in Rio Grande do Sul and came to know Livio Zambeccari, which turned out to be the start of a close and lasting friendship between two men who politically and in terms of their temperaments had a good deal in common.[1][14]

On 4 October 1836, while engaged in combat against the armies of the boy emperor, Zambeccari was captured at the Battle of Fanfa Island and taken prisoner. He was led in chains to a prison ship moored in the harbour at Porto Alegre. Later he was transferred to a more permanent place of detention in the Fortress of Santa Cruz near Rio de Janeiro. He was held as a prisoner of war for slightly more than three years. This put an end to his participation in the fighting, but he was able to remain active, producing a number of geographical maps and watercolour paintings. In addition, he translated into Portuguese a number of political and philosophical works by Félicité de La Mennais and Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi. Release, when it came, was predicated on a conditional amnesty. On 2 December 1839 Zambeccari was escorted to an English ship and sent back to Europe.[1][15]

He was landed at Portsmouth and made his way to London. The cause of Italian liberation from (primarily) Austrian domination and/or control was popular with the political class in England, and London was home to a large number of Italian political exiles. Among these, Zambeccari met Giuseppe Mazzini, who had been living in London since 1837. Long before they met, Mazzini had been aware of Zambeccari, whom he regarded as a "republican of integrity" ("un repubblicano integerrimo"). In South America Zambeccari had publicised and promoted Mazzini's Young Italy movement through his journalism, and in London Mazzini was able to express his appreciation of this in person, and to introduce Zambeccari to the principal Italian revolutionaries present in London at the time.[1] From London he moved on to France.[16]

Back in Italy

Livio Zambeccari was back in Italy by the end of 1840, but he remained under a ban when it came to any attempt to access territories controlled as part of the Papal States. Before 1860 that included not just Rome but also Romagna including, under arrangements re-instated in 1815, Bologna. Unable to return, even now, to his home city, Zambeccari made his new home between Lucca and Florence, close to the homes of his Tuscan relatives.[17] In Lucca he was staying close to the ducal court, and it was through the intervention with the Papal authorities of Duke Charles Louis that during 1841 Zambeccari was finally permitted to return home to Bologna. In his home city, Count Zambeccari did his best to pass himself off as a lifelong student and scholar with a passion for geography and other natural sciences. Nevertheless, he is of greater interest to subsequent generations of historians because of the way in which throughout (and beyond) the 1840s he participated actively in the events which led to Italian unification. As soon as he arrived in Bologna he established contacts with local Mazzinian and Carbonari groups dedicated, according to the "revolutionary" narrative of the times, to the ending of tyranny and the establishment of constitutional government. He worked closely with Nicola Fabrizi, a fiery and committed leader in the network of risorgimento patriots.[1][5][18]

There had been a falling out between Fabrizi and Mazzini, but Fabrizi nevertheless entrusted Zambeccari with a leading role in a revolt that was to be triggered during 1843 by the launch of an insurrection of Sicily and Naples which would then spread to the rest of the Italian peninsular, in ways which would lead to the expulsion of Austrian armies from the central and northern parts of the territory, followed by the creation of a united Italy. Mazzini, despite his own reputation as a manufacturer of poorly thought-through schemes, refused to back Fabrizi's project, highlighting the risk that Sicily was more likely to declare independence than lead a glorious campaign through Italy ending in the achievement of unification. In Bologna, Zambeccari nevertheless played his part as one of the leaders of the so-called "Moti di Savigno", a patriot insurrection launched in the little town of Savigno, some 15 miles outside Bologna. The exercise was a failure, chiefly remembered in retrospect for the brutality with which it was put down. Zambeccari was not one of the 19 participants sentenced to death, but he was banned from the Bologna region.[1] Several of those who faced trial after the fiasco spent their exile in France, and it is possible that Zambeccari was, at least for some of the time, one of these.[19]

The installation of Pope Pius IX in June 1846 was marked by the declaration of an amnesty for persons determined to have been convicted for "political crimes" in the Papal states, which took effect on 17 July 1846, a month following the new pope's enthronement. Zambeccari was living in hiding in Tuscany by this time, and as a beneficiary from the amnesty, in July 1846 he took the opportunity to return to Bologna.[2][20][21]

The following year Zambeccari and other prominent members of the patriot persuasion found themselves excluded from positions of leadership within the city's newly established "Guardia Civica pontificia" (loosely, "civic guard [in the Papal states]"), modelled on an equivalent body recently established in Rome and created, in response to popular pressure, at the instigation of Cardinal Amat, the conservative and politically astute churchman who at this time was serving as papal legate in Bologna. The creation of this body of (initially 500) men mandated to undertake some of the duties subsequently assigned to police forces a widely welcomed. But there was a striking absence of consensus over what it was for. For moderates, it represented a guarantee of civic freedoms already won while for others it was a potential guarantee of civic freedoms that would be won in the future. For Mazzinians and other risorgimento patriots the popular idea of the "guardia civica" was seen as the creation of a nucleus of a citizen army that might be built up to take in the Austrians and win Italian independence. It was noted that the men who emerged as leaders in the new organisation under the discrete but effective choreography of the cardinal, such as Marco Minghetti, Annibale Ranuzzi and Giuseppe Tanari were all firmly on the "moderate" end of the political spectrum. Mazzinian aspirations were extremely popular in Bologna, however. Faced with a barrage of press criticism and the risk of rioting on the streets (or worse) Amat relented: Zambeccari was appointed to an official leadership position within the "guardia civica". The papal authorities and their representatives in the city nevertheless continued to observe his doings with suspicion, however.[1][20]

1848

With the outbreak in March 1848 of what came to be known as the First Italian War of Independence Zambeccari placed himself at the head of a group of between 300 and 400 armed men, which came to be known as the "Cacciatori dell’Alto Reno" ("Hunters of the Upper Rhine"). With his little force crossed the border into the Veneto, a Crown land of the Austrian Empire since 1815. He launched his incursion without seeking or obtaining the consent of General Giovanni Durando, the military commander appointed by the pope to guard and where necessary defend the border separating the Papal States from the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia.[lower-alpha 4] Zambeccari's force entered Modena on 21 March 1848: there are reports that the appearance of a small army of "liberals" was cheerfully welcomed by the Modenesi city folk, and a provisional government was declared by local risorgimento patriots.[1][23]

During the first part of April 1848 Zambeccari led his men through the southern districts of the Veneto, passing through Occhiobello, Badia Polesine, Montagnana and the nearby Castle of Bevilaqua. On 9 April 1848, he commandeered the castle (which had not been used for serious military operations for more than three centuries) which he commandeered and used a base from which to launch a rapid series of raids against Austrian military positions. This marked the launch of a regional guerrilla war with which Zambeccari's name would subsequently be associated. By the time the Austrian army arrived ten days later and destroyed what remained of the castle fortifications Zambeccari had moved on, but the guerrilla campaign continued.[24][22] Following the well-honed tactics of guerrilla warfare, Zambeccari's battalion moved rapidly, avoiding set-piece battles. As the fighting spread the reputation of his "Cacciatori dell’Alto Reno" grew: orders were received from Generals Alberto Ferrero and Alessandro Guidotti that they should defend the strategically important line of the Piave and then withdraw to Treviso, where the city folk had succeeded in expelling the forces of the Austrian garrison the previous month. As they reached Treviso they came across and clashed with Austrian military units. The fighting ended when, under circumstances that would remain controversial, Zambeccari broke off the engagement and fled in the direction of Mestre.[1]

During May 1849 Zambeccari and his men took part in the defence of Vicenza, where the citizens had rebelled against their Austrian garrison with particular violence. The armies of the Papal States under the command of General Giovanni Durando took a lead in the defence of the city. During May 1848 a combination of papal forces, a large civic militia and Zambeccari's "Cacciatori dell’Alto Reno" successfully drove back ferocious onslaughts by an Austrian army under Field Marshal Radetzky. In June 1848 Radetzky returned with overwhelming forces. It was reported that the Austrian commander was so impressed by the courage and resolution displayed by the city's defenders that he allowed the fighters to surrender honourably, without having to give up their arms or being taken prisoner. Meanwhile, Zambeccari's group became increasingly integrated into the forces of the Papal States. Ten days before the surrender of Vicenza, early in June 1848, he was given command of the forces defending the stronghold of Treviso, which nevertheless fell to the Austrians following a savage bombardment four days later. Over 300 died in the savage fighting and there were approximately 1,600 wounded. As at Vincenza, Radetzky agreed to an honourable surrender.[1][25]

In September 1848 he placed himself at the service of the Republic of San Marco, the break-away region surrounding Venice which achieved a precarious and variable measure of freedom from Austrian control between March 1848 and August 1849. He was able to contribute to General Guglielmo Pepe's rebel/patriot force a group of armed men that had, in the previous few months, more than doubled in size and achieved several significant successes in guerrilla sorties against units of the Austrian army.[26] A couple of months later as the approaching winter heralded a likely break in the fighting, the Papal States were plunged into intensified crisis by the assassination in Rome, on 15 November 1848, of Justice Minister Pellegrino Rossi. Excited mobs took over the city streets, and on 24 November 1848 the pope fled, making for the relative safety of Gaeta, along the coast road to towards Naples. Over the next few weeks, the revolutionary government of what became the so-called Roman Republic emerged. These developments prompted Zambeccari to leave Venice and return home to Bologna. He arrived with his battalion on 22 December 1848: in the pioneering election held on 21 January 1849 "Colonel Zambeccari" (as he was by this time frequently identified) was elected to membership of the short-lived Roman Constitutional Assembly.[2] He then continued on south over the mountains to Rome, and was present when the assembly met overnight on 8/9 February 1848 and the Roman Republic was proclaimed.[1] Many of the 24 deputies in the delegation from Bologna were, like Zambeccari himself. prominent representatives of the local freemasonry.[27]

1849

In April 1849 Zambeccari was appointed commander in chief ("comandante superiore") in respect of the defence of Ancona. He was supported by approximately 4,000 patriot volunteers from various Italian regions. The political context was one in which, following the declaration of the Roman Republic, the city of Ancona had declared itself independent of papal rule (which was in any case somewhat theoretical as long as the pope was exiled in Gaeta). The Austrians had come to an agreement with the exiled pope and were openly fighting in order to restore the Papal States and return Ancona to them. On the military front, Zambeccari's handling of the Ancona command did not go uncriticised. There were those who found his strategy unnecessarily passive and defensive. Through his chosen strategy he was nevertheless successful in repelling several Austrian attacks, before being obliged to raise the white flag following a heavy bombardment.[1][28]

Shorter exile: 1849-1854

By the early summer of 1849, as the Austrians systematically rapidly recovered the rebel cities one after another, it was clear that viewed as a war of independence, the Italian uprisings of 1848/49 had failed. On 21 June 1849, after nearly a month of heavy artillery bombardment, Ancona formally surrendered, one of the last cities to do so. Zambeccari had been permitted to leave the previous day. Like many of the risorgimento activists of the '48 generation, he now made his way to Corfu, which had been a designated "British protectorate" since 1815.[29] Daniele Manin and Niccolò Tommaseo were among his more distinguished fellow exiles. As Italian war refugees continued to arrive on the island Zambeccari set about trying to set up a committee to deal with the basic needs of the patriots. His incessant organisational activities aroused the suspicion of the British authorities, however. There were concerns that as an effective liberation activist in Italy and South America - pursuing causes of which British governments tended to approve - Zambeccari might now inflame a corresponding desire for independence among Corfiotes - a cause for which British governments could muster no enthusiasm. So they arrested him.[30] During or before 1851 he was transferred to Patras in neighbouring Greece.[1][31][32] Patras, like Corfu, also became home to many fugitive Italian patriots and others. One of these, a man from Naples called Oronzio Spinazolla, was arrested for theft during the first part of 1853, and following interrogation had managed to find himself charged as an accomplice in a (failed) conspiracy to assassinate King Otto. Hoping to ingratiate himself with his interrogators, Spinazolla implicated several of his former comrades from the Austro-Italian wars of 1848/49. At some point during that time Spinazolla had worked in a secretarial capacity of Zambeccari, who was already a relatively well-known - and from some perspectives notorious - member of the exiled Italian community in Patras. Zambeccari was one of those whom Spinazolla implicated. Austrian diplomats, who were not without influence in the fledgling Greek kingdom, seized their opportunity and applied pressure. He was moved on again, this time to Athens and spent several months in prison. It was in 1854 that Zambeccari was, according to at least one source, deported from Greece. Elsewhere it is indicated that he was driven out of Greece by a Cholera epidemic.[1][31]

During his five-year exile in Corfu and Greece, with the possible exception of the few months he spent in prison, Zambeccari seems to have been free to use his time more or less as he wished. He dedicated himself to scientific studies, as he had earlier in life when faced with enforced abstention from patriot activism. Matters on which he focused included aspects of Mineralogy, Botany, Numismatics and assembling ancient artefacts. One topic from which, as far as is known, he abstained was politics.[1][33] When first he arrived on Corfu Zambeccari was appalled that almost all of the 1848 Italian veterans he encountered were living in abject penury; he attracted comment by distributing packages of 300 Obols. Soon he became tormented by his own lack of money. For Zambeccari there turned out to be a solution available, however. He was able to sell off, from his Corfiote exile, various assets including, notably, the family estate he had inherited at San Marino di Bentivoglio in the countryside alongside the road from Bologna to Ferrara.[1][5]

Later years

In 1854, Athens was hit by a particularly vehement cholera epidemic. After a period of serious illness, Zambeccari was able to return to Italy. At this stage, he returned not to anywhere in the Papal States, but to Turin. He actively pursued his work on social and political issues and became a believer in Mesmerism, which had become fashionable.[1] In 1857 he backed the formation of the Bologna branch committee of the "Società nazionale italiana", an association launched initially in Turin (Piedmont) in August 1857 in order to promote Italian unification based around the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont. The "Società" was launched with the support of Count Cavour, the head of the Piedmontese government since 1852 and, like Zambeccari, an actively engaged Freemason. Some sources hint at meetings between Zambeccari and Cavour at which, presumably, the principal topic of mutual interest would be how to achieve Italy's liberation and political unification. The hints remain speculative, however.[1][34]

After July 1859 it was clear that, with French military and political backing, Italian unification under the leadership of the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont had been achieved, even if many critical questions as to its extent and character remained unanswered. On 8 October 1859, Livio Zambeccari teamed up with seven influential brother Masons in the region to establish the "Ausonia Lodge" in Turin. On 20 December 1859 that formed the basis for the Grand Orient of Italy, recreating an earlier incarnation of the Grand Orient that had been suppressed in 1814 after French revolutionary idealism (with which Masonry was closely associated at the time) fell abruptly out of favour.[1][35][36] Towards the end of 1860 he served briefly as interim Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy. He accepted a further appointment to the same position - again on an interim basis - between October 1861 and February 1862.[37] He made a major contribution to reorganising the secret society,[38] earning the plaudit from at least one admirer that he proved himself "the indefatigable proponent of Italian masonic unity".[1][39] In 1860, in his capacity as a Prince of the Pink Cross of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite ("Principe Rosa-Croce del Rito scozzese antico ed accettato"), Zambeccari founded the "Human Concord Lodge of Bologna" ("loggia Concordia Umanitaria di Bologna").[40][41] In 1862 he also became a full member of the "Loggia Osiride" ("Osiris [masonic] lodge") in Turin.[35][42]

The final two or three years of Zambeccari's life were marred by a series of disappointments. He was also held back by the deteriorating state of his health. In February 1860 he sought election to the Bologna city council but failed to gain election.[1] After the liberation war moved south Zambeccari participated as a volunteer at the Battle of the Volturno, fought in the Naples region early in October 1860. Although the outcome of the battle was indecisive in purely military terms, it quickly became clear that the military and political initiative remained with Garibaldi. At the personal invitation of Garibaldi, whom he had first gotten to know when they were both patriot exiles in South America during the 1830s, Zambeccari accepted a position as inspector-general in the anti-Bourbon "Army of the South" and director of Garibaldi's "Ministry of War". The precarious state of his health forced him to surrender his postings and return to Bologna in November 1860, however. After this, he was, for much of the time, condemned to remain in or close to Bologna. He stayed in touch, as far as possible, with patriot comrades and became involved with the "Amici dei popoli" ("Friends of the people") workers' welfare association. Livio Zambeccari died at Bologna on 2 December 1862.[1][7]

Notes

- ↑ "... io sono amicissimo di Zambeccari, ma siate certo che in caso di pericolo, e risoluzione e scienza militare, è purtroppo vero che non val nulla. Ed è un gran male perché uomo attaccatissimo al suo paese".[1]

- ↑ Alferi's original stage tragedy "Bruto Primo", inspired by the American Revolutionary War and first staged in 1786/87, is dedicated "to the very dear man of liberty, General Washington" ("al chiarissimo e libero uomo il generale Washington").[11]

- ↑ "...ad essere uno degli ispiratori e teorici della rivoluzione repubblicana".[1]

- ↑ General Durando was later called upon to explain. He says so: "... as a general, I would not have given them orders to pass [through the frontier] ... They wanted to pass: I did not oppose them, and I sent instructions and orders whereby they might be able to defend themselves militarily". ("... non avrei come generale dato loro ordine di passare ... Hanno voluto passare; non mi sono opposto ed ho loro mandato istruzioni ed ordini, onde sappian guardarsi militarmente".[22]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Giacomo Girardi (2020). "Zambeccari, Livio. – Nacque a Bologna il 30 giugno 1802, figlio del conte Francesco e di Diamante Negrini". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Treccani, Roma. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mario Menghini (1937). "Zambeccari, Livio, conte. - Patriota, nato a Bologna il 30 giugno 1802, morto ivi il 2 dicembre 1862". Enciclopedia Italiana. Treccani, Roma. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Daniela Marzola Fialho. "Ó cartógrafo revolucionário". Para uma história da cartografia como documento de identidade urbana. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas), Porto Alegre. pp. 128–131. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 Mirtide Gavelli. "Zambeccari Livio 1802 - 1862". Instituzione Bologna Musei (Museo Civico del Risorgimento). Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ Timina Caproni Guasti; Achille Bertarelli. "Francesco Zambeccari (1752-1812)". Grandi personaggi / Zambeccari aeronauta. Roberto Spagnoli (Aerostati.It: il sito dell' aerostatica Italiana). Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- 1 2 Luciano Rossi (2019). Tito Livio Zambeccari. Booksprint. pp. 175–179. ISBN 978-8824926942. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Franco Cenni (January 1965). Zambeccari, o Revolucionário Sonhador. Livraria Martins. pp. 97–103. ISBN 9788531406713. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Alessandro Bonvini (January 2018). "La actividad mazziniana en América Latina: desde Brasil a Montevideo. Propaganda, prensa y asociación". Los Exiliados del Risorgimento. El Mazzinianesismo en el Cono Sur. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Memoria y sociedad), Bogotá. 22 (44): 44–65. doi:10.11144/javeriana.mys22-44.ermc. ISSN 0122-5197. S2CID 149589021. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ Dario Calzavara; Carmine Cassino (April 2012). "Brazil: 'Eldorado' or a penal settlement?". The Nineteenth-Century Italian Political Migration to the Lusophone. Mediterranean Center of Social and Educational Research, Rome. pp. 121, 117–124. ISSN 2039-2117.

- ↑ John Paradise (letter writer); Dorothy Twohig (editor-compiler); Mark A. Mastromarino (editor-compiler); Jack D. Warren (editor-compiler) (2 April 1790). "To George Washington from John Paradise .... Editor's Footnote 1". Founders online .... Washington Papers. The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

{{cite web}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ↑ Alessandro Bonvini (2018). "Carbonarios, comuneros e radicáis" (PDF). Avventurieri, esuli e volontari. Storie atlantiche del Risorgimento. Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici, Università degli Studi di Salerno. p. 105. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ "Livio Zambeccari (1802-1862)". La Storia. L'Istituzione Villa Smeraldi (Museo della Civiltà Contadina), Città metropolitana di Bologna. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ David Gelber. "The Gaucho Who Unified Italy. Garibaldi in South America: An Exploration by Richard Bourne". book review and synopsis. Literary Review. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ Guilherme d'Andrea Frota. "I protagonisti .... Il conte Tito Livio Zambeccari, bolognese di nascita (30-06-1802)..." (PDF). L'importante presenza italiana nella “rivoluzione degli straccioni” in Brasile e l’intervento navale di Garibaldi. Ministero della Difesa (Marina Militare). pp. 2–7. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ↑ E. Spartaco, "Livio Zambeccari per Enrico Spartaco", Napoli, Stabilimento tipografico Strada S. Sebastiano, 1861, p.20

- ↑ Elena Pierotti (September 2016). "Risorgimento in penombra". Luciano Atticciati & Simone Valtorta (storico.org). Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ↑ Serena Presti Danisi (2019). "Gli uomini della rivoluzione" (PDF). La formazione dell’élite politica democratica nella Repubblica romana del 1849. Università degli Studi di Padova. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ↑ "Bottrigari Gaetano 1807 - 1889". Instituzione Bologna Musei (Museo Civico del Risorgimento). Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- 1 2 Mirtide Gavelli. "Uniforme della Guardia Civica pontificia". Instituzione Bologna Musei (Museo Civico del Risorgimento). Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ↑ Redazione (9 February 2021). "Le riforme de Pio IX". La Repubblica Romana: Dal potere temporale del Pontefice al "Dio e Popolo". L'incontro, Torino. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- 1 2 Andrea Spicciarelli (July 2020). "Il contributo delle Legazioni pontificie alla difesa di Vicenza (maggio-giugno 1848)" (PDF). Associazioni Risorgimentali Italiane. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ "21 mar: La colonna Zambeccari entra a Modena". Cronologia di Bologna dal 1796 a oggi: 1848. Biblioteca Salaborsa. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ "9 apr: I volontari dell'Alto Reno alla difesa del Piave". Cronologia di Bologna dal 1796 a oggi: 1848. Biblioteca Salaborsa. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ "20 mag: I corpi franchi combattono a Vicenza e Treviso". Cronologia di Bologna dal 1796 a oggi: 1848. Biblioteca Salaborsa. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ Donato Tamblé (September 2011). "Le truppe romane in Veneto e alla difesa di Venezia nel 1848-49" (PDF). Le Armi diSan Marco .... La potenza militare veneziana dalla Serenissima al Risorgimento. Società Italiana di Storia Militare, Roma. pp. 287–332. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ "21 gen: Elezione a suffragio universale dei rappresentanti all'Assemblea Costituente". Cronologia di Bologna dal 1796 a oggi: 1849. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ Marco Severini (April 2016). "I grandi assedi del 1849: Ancona". ISBN 978-88-97912-19-4.

- ↑ Ersilio Michel [in Italian] (1950). "Emigrazione politica: Esuili Italiani nelle Isole Ionie (1849)". Rassegna storica del Risorgimento. Istituto per la storia del Risorgimento italiano. pp. 323–352, 324, 329. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ Christos Aliprantis (10 September 2019). "Lives in exile: foreign political refugees in early independent Greece (1830–53)". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. Cambridge University Press.

- 1 2 Christos Aliprantis; Catherine Brice (editor-compiler) (2020). Foreign political refugees, bureaucratic controls and cultures of surveillance in the Kingdom of Greece (1833-1862). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 16–31, 27. ISBN 978-1-5275-4812-1. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Christos Aliprantis (2007). "Political Refugees of the 1848–1849 Revolutions in the Kingdom of Greece: Migration, Nationalism, and State Formation in the Nineteenth-Century Mediterranean". Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 37/1: 1–33. doi:10.17863/CAM.40481. ISSN 0738-1727. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ↑ Claudio Santini (24 September 2010). "Gli ostacoli del conte amico di Garibaldi". Corriere di Bologna. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ↑ "La massoneria". Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- 1 2 "Livio Zambeccari, interim 08-10-1861/01-03-1862". Grande Oriente d’Italia, Roma. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ↑ "Il Primo centenario della R. M. L. Ausonia". Massoneria Universale - Cominione Italiana: Valle del Po. 8 October 1959. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ↑ "Livio Zambeccari, interim 1860". Gran Maestri. Grande Oriente d’Italia, Roma. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ↑ "Massoneria bolognese 1802 - 1929". Istituzione Bologna Musei- Area Storia e Memoria. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ↑ G. Leti, Carboneria e massoneria nel Risorgimento italiano, Genova 1925

- ↑ Luca Irwin Fragale, La Massoneria nel Parlamento. Primo novecento e Fascismo, Morlacchi Editore, 2021, p. 306.

- ↑ Sergio Sarri (author-compiler); Carlo Manelli (author-compiler); Eugenio Bonvicini (author-compiler); Manlio Cecovini (prefazione) (2 October 2014). Fondazione della Loggia Concordia a Bologna. Youcanprint. p. 85. ISBN 978-8891159144. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

{{cite book}}:|author1=has generic name (help);|work=ignored (help) - ↑ V. Gnocchini, L'Italia dei Liberi Muratori, Mimesis-Erasmo, Milano-Roma, 2005, pp.276-277