| Longtown Castle | |

|---|---|

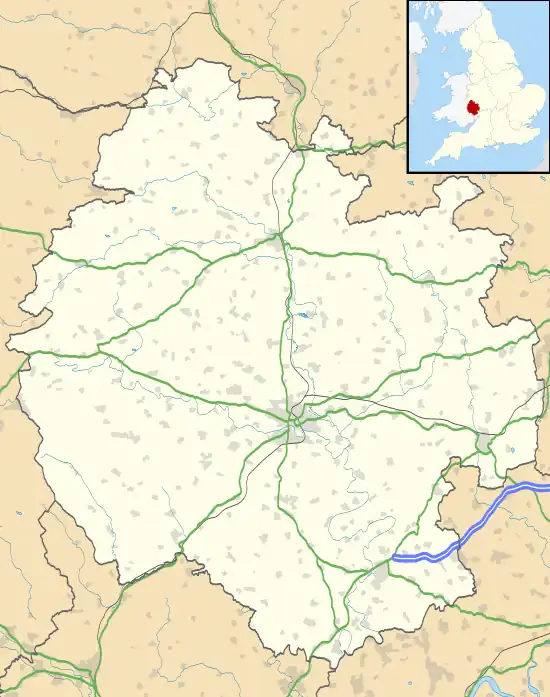

| Longtown, Herefordshire, England | |

The keep and inner gatehouse, 2007 | |

Longtown Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51°57′22″N 2°59′28″W / 51.9562°N 2.9910°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference SO320291 |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Stone |

Longtown Castle, also termed Ewias Lacey Castle in early accounts, is a ruined Norman motte-and-bailey fortification in Longtown, Herefordshire. It was established in the 11th century by Walter de Lacy, reusing former Roman earthworks. The castle was then rebuilt in stone by Gilbert de Lacy after 1148, who also established the adjacent town to help pay for the work. By the 14th century, Longtown Castle had fallen into decline. Despite being pressed back into use during the Owain Glyndŵr rising in 1403, it fell into ruin. In the 21st century the castle is maintained by English Heritage and operated as a tourist attraction.

History

Earlier sites

The first fortification at Longtown was a Roman fort, close to a Roman road that ran along the borderlands.[1] The fort was square, and protected by a ditch and a timber palisade.[2] The Roman defences were reinforced, probably in 1055, after a Welsh attack on Hereford.[1]

Initial construction

After the Norman invasion of England and Wales in 1066, a small castle began to be built at Pont Hendre, close to the site of the current castle, by Walter de Lacy in order to protect the river crossing there.[3] Following Welsh attacks, Walter abandoned Pont Hendre and instead started to build a castle at Longtown, on the site of the old Roman fort.[1] The early castle was occasionally also called Ewias Lacey, named after the wider lordship; "Ewias" was a term meaning "sheep district".[4]

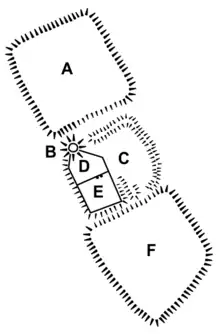

Longtown Castle was designed as a motte and bailey castle, on high ground alongside the River Monnow.[5] More defensible sites on higher ground existed nearby, but this location was strategically well located close to the River, an important transport route.[6] It had a 10-metre (33 ft) high motte and an unusual rectangular bailey design around 125 metres (410 ft) by 110 metres (360 ft), divided into three parts, two baileys in the west and one in the east, each capable of being defended independently and enclosing around 1.21 hectares (3.0 acres) in total.[7] The 12th-century castle was built primarily of timber with at least some stone in its design, but this stone was then reused when the castle was rebuilt in the 13th century.[8] Two circuits of earthworks to the north and south of the castle, possibly with wooden palisades, enclosed the early settlement of Longtown.[9] The region was troubled for the rest of the century, with revolts by the local Welsh against Anglo-Norman rule.[10]

The de Lacys lost their lands in the region after conspiring against William II, but around 1148, Gilbert de Lacy regained the estates.[1] Gilbert probably then rebuilt the castle in stone, at a considerable cost of £37, financed by the construction of a new borough alongside it.[11] The stone keep was constructed in the form of a circular great tower, with walls 5-metre (16 ft) thick and three turrets spaced evenly around the outside and a hall on the first floor.[12] This circular design is particular to the Welsh Marches, and is also seen at Skenfrith and Caldicot.[13] The reason for this choice is unclear, as it appears to have carried few military advantages.[14] The stonework is made up of sandstone rubble with cut ashlar detailing; the walls are around 4-metre (13 ft) thick, but the keep's foundations are extremely shallow.[15] An inner gate to the western baileys was built to a simple design with two small turrets, and seems to have been fitted with a portcullis, while a 2-metre (6 ft 7 in) thick wall encircled the rest of the inner western bailey; another stone wall seems to have protected the outer half of the bailey.[16] Inside the inner western bailey appears to have been the castle's great hall and other service buildings.[17]

Expansion and decline

The de Lacy family controlled Longtown Castle until Walter de Lacy's death in 1234.[18] John Fitzgeoffrey then acquired the castle, during a period of increased conflict and tension between the Welsh princes Llywelyn the Great and Dafydd ap Llywelyn and the English marcher lords.[19] The castle reverted to the de Lacy family and became part of the inheritance of Margery (or Margaret) de Lacy, daughter of Gilbert de Lacy, who had predeceased his father Walter de Lacy, Lord of Meath, and his wife Isabel Bigod, daughter of Sir Hugh Bigod, 3rd Earl of Norfolk. Marjory married John de Verdun of Alton, son of Theobald le Botiller and Roesia de Verdun. The de Verduns struggled with local lawlessness and the Welsh revolts which continued until the end of the century.[19] King Edward I temporarily confiscated the castle and estates from John's son, Theobald de Verdun, 1st Baron Verdun. On Theobald's death, the castle passed to his son Theobald de Verdun, 2nd Baron Verdun, who died in 1316 without surviving male heirs, whereupon the castle became part of the inheritance of his 2nd daughter Elizabeth and by right of his wife passed to her husband Bartholomew Burghersh, 1st Baron Burghersh.[19] The castle continued to be used as a fortification, and in 1317 orders were given to garrison it with 30 men.[19]

The castle began to decline in importance, however, and in 1369 passed to the Despensers and then the Beauchamps, neither of whom used the castle.[19] It was temporarily refortified by Henry IV in response to the Owain Glyndŵr uprising in North Wales in 1403.[20] The Nevilles acquired the property in the 15th century and it remained in the control of the Lords of Abergavenny until the 1970s.[19] After the Black Death the town's population fell away sharply as well, the protected area north of the castle was abandoned, and by the 16th century it was no longer a functioning trading centre.[21]

It is unclear if the castle and town played any part in the English Civil War between 1642–45, although cannonballs from the period have been discovered within the castle.[3] Local oral tradition states that the castle was slighted, or deliberately destroyed, during the war.[22] Stones from the castle were used for local building work by the 17th century onwards, and by the 18th century a house and shop had been constructed in the eastern bailey of the castle, along with a yard and garden.[22] A gallows operated at the castle until 1790.[22] Buildings continued to encroach on the castle. By the end of the 19th century a school and a house, Castle Lodge, had been built in the castle grounds.[22] Other buildings were built as lean-tos against the castle walls.[22]

20th - 21st centuries

Longtown Castle was acquired by the Ministry of Works in the 1970s.[23] It was in a poor condition and extensive restoration work was carried out, including the removal of many of the buildings that had encroached on the walls.[24] In the 21st century, the central parts of Longtown Castle, including the ruined keep, the internal gatehouse and fragments of the curtain wall, are maintained by English Heritage as a tourist attraction, although the wider earthworks lie on common land.[25] In 2016, the Longtown and District Historical Society obtained Heritage Lottery Funding for a community archaeology project to research Longtown Castle over the next two years.[26] The castle is protected as a scheduled monument.[27]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "History of Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ Smith 2003, p. 5; Buteux, Victoria (2005). "Archaeological Assessment of Longtown, Hereford and Worcester" (PDF). English Heritage and Worcestershire County Council. p. 4. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; "History of Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- 1 2 Buteux, Victoria (2005). "Archaeological Assessment of Longtown, Hereford and Worcester" (PDF). English Heritage and Worcestershire County Council. p. 2. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; "History of Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ Buteux, Victoria (2005). "Archaeological Assessment of Longtown, Hereford and Worcester" (PDF). English Heritage and Worcestershire County Council. p. 2. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; Smith 2003, p. 6

- ↑ Pettifer 1995, p. 100

- ↑ Smith 2003, p. 2

- ↑ Prior 2006, p. 125; Smith 2003, p. 12; Buteux, Victoria (2005). "Archaeological Assessment of Longtown, Hereford and Worcester" (PDF). English Heritage and Worcestershire County Council. p. 4. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; Pounds 1994, p. 24; "History and Research: Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Buteux, Victoria (2005). "Archaeological Assessment of Longtown, Hereford and Worcester" (PDF). English Heritage and Worcestershire County Council. p. 4. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; "History and Research: Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; Smith 2003, p. 27

- ↑ Buteux, Victoria (2005). "Archaeological Assessment of Longtown, Hereford and Worcester" (PDF). English Heritage and Worcestershire County Council. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Smith 2003, p. 7

- ↑ "History and Research: Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; "History of Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ Goodall 2011, p. 181; "History and Research: Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; Pettifer 1995, p. 100

- ↑ Goodall 2011, p. 181

- ↑ King 1991, p. 99

- ↑ King 1991, p. 50; Smith 2003, p. 14; "Longtown Castle". Gatehouse. 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ King 1991, p. 117; Smith 2003, pp. 14–15; "History of Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ↑ Buteux, Victoria (2005). "Archaeological Assessment of Longtown, Hereford and Worcester" (PDF). English Heritage and Worcestershire County Council. p. 4. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ "History and Research: Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; "Longtown Castle". English Heritage. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Smith 2003, p. 8

- ↑ Pettifer 1995, p. 100; "History and Research: Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Buteux, Victoria (2005). "Archaeological Assessment of Longtown, Hereford and Worcester" (PDF). English Heritage and Worcestershire County Council. pp. 2, 7. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smith 2003, p. 9

- ↑ Smith 2003, p. 3

- ↑ Smith 2003, pp. 3, 9

- ↑ Smith 2003, p. 1; "Longtown Castle". Gatehouse. 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.; "History and Research: Longtown Castle". English Heritage. 2004. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ↑ Cook, Martin (2016). "The Castle Studies Group Bulletin" (PDF). Castle Studies Group. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ↑ "Longtown Castle". Gatehouse. 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

Bibliography

- Goodall, John (2011). The English Castle. New Haven, US and London, UK: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300110586.

- King, D. J. Cathcart (1991). The Castle in England and Wales. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-00350-6.

- Pettifer, Adrian (1995). English Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851157825.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Prior, Stuart (2006). A Few Well-Positioned Castles: The Norman Art of War. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 9780752436517.

- Smith, Nicky (2003). "Longtown, Herefordshire: a Medieval Castle and Borough, Archaeological Investigation Report Series AI/26/2003". Archaeological Investigation Report Series. London, UK: English Heritage. ISSN 1478-7008.