| The Home of Cricket | |||||

Lord's current logo | |||||

The Pavilion | |||||

| Ground information | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | St John's Wood, London, England | ||||

| Coordinates | 51°31′46″N 0°10′22″W / 51.5294°N 0.1727°W | ||||

| Establishment | 1814 | ||||

| Capacity | 31,100[1] | ||||

| Owner | Marylebone Cricket Club | ||||

| Tenants | England and Wales Cricket Board | ||||

| End names | |||||

Nursery End  Pavilion End | |||||

| International information | |||||

| First Test | 21–23 July 1884: | ||||

| Last Test | 28 June – 2 July 2023: | ||||

| First ODI | 26 August 1972: | ||||

| Last ODI | 15 September 2023: | ||||

| First T20I | 5 June 2009: | ||||

| Last T20I | 29 July 2018: | ||||

| First WODI | 4 August 1976: | ||||

| Last WODI | 24 September 2022: | ||||

| First WT20I | 21 June 2009: | ||||

| Last WT20I | 8 July 2023: | ||||

| Team information | |||||

| |||||

| As of 8 July 2023 Source: ESPNcricinfo | |||||

Lord's Cricket Ground, commonly known as Lord's, is a cricket venue in St John's Wood, London. Named after its founder, Thomas Lord, it is owned by Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) and is the home of Middlesex County Cricket Club, the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB), the European Cricket Council (ECC) and, until August 2005, the International Cricket Council (ICC). Lord's is widely referred to as the Home of Cricket[2] and is home to the world's oldest sporting museum.[3]

Lord's today is not on its original site; it is the third of three grounds that Lord established between 1787 and 1814. His first ground, now referred to as Lord's Old Ground, was where Dorset Square now stands. His second ground, Lord's Middle Ground, was used from 1811 to 1813 before being abandoned to make way for the construction through its outfield of the Regent's Canal. The present Lord's ground is about 250 yards (230 m) north-west of the site of the Middle Ground. The ground can hold 31,100 spectators, the capacity having increased between 2017 and 2022 as part of MCC's ongoing redevelopment plans.

History

Background

.jpg.webp)

Acting on behalf of members of the White Conduit Club and backed against any losses by George Finch, 9th Earl of Winchilsea and Colonel Charles Lennox, Thomas Lord opened his first ground in May 1787 on the site where Dorset Square now stands, on land leased from the Portman Estate.[4] The White Conduit moved there from Islington, unhappy at the standard of the ground at White Conduit Fields, soon afterwards and reconstituted themselves as Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC). It was thought that the establishment of a new ground would offer more exclusivity to its members, with White Conduit Fields considered too far away from fashionable Oxford Street and the West End.[5] The first match played at the new ground saw Middlesex play Essex.[6][7] In 1811, feeling obliged to relocate because of a rise in rent, Lord removed his turf and relaid it at his second ground. This was short-lived because it lay on the route decided by Parliament for the Regent's Canal, in addition to the ground being unpopular with patrons.[7][6]

The "Middle Ground" was on the estate of the Eyre family, who offered Lord another plot nearby; and he again relocated his turf. This new ground was originally a duck pond on a hill in St. John's Wood, which gives rise to Lord's famous slope,[8] which at the time was recorded as sloping down 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) from north-west to south-east, though in actuality the slope is 8 ft 1 in (2.46 m).[9] The new ground was opened in the 1814 season, with the MCC playing Hertfordshire in the first match on the ground on 22 June 1814.[10][6]

Early history

A tavern was built for Lord in 1813–14,[11] followed by a wooden pavilion in 1814.[12] First-class cricket was first played on the present ground in July 1814, with the MCC playing St John's Wood Cricket Club.[13] The first century to be scored at the ground in first-class cricket was made by Frederick Woodbridge (107) for Epsom against Middlesex, with Epsom's Felix Ladbroke (116) recording the second century in the same match.[5] The annual Eton v Harrow match, which was first played on the Old Ground in 1805, returned to the present ground on 29 July 1818. From 1822, the fixture has been almost an annual event at Lord's.[14]

Lord's witnessed the first double-century to be made in first-class cricket when William Ward scored 278 for the MCC against Norfolk in 1820.[5] The original pavilion, which had recently been renovated at great expense,[5] was destroyed by fire following the first Winchester v Harrow match on 23 July 1823, which destroyed nearly all of the original records of the MCC and the wider game.[15] The pavilion was promptly rebuilt by Lord.[16] In 1825, the future of the ground was placed in jeopardy when Lord proposed developing the ground with housing at a time when St John's Wood was seeing rapid development. This was prevented by William Ward,[6] who purchased the ground from Lord for £5,000. His purchase was celebrated in the following anonymous poem:

- And of all who frequent the ground named after Lord,

- On the list first and foremost should stand Mr Ward.

- No man will deny, I am sure, when I say

- That he's without rival first bat of the day,

- And although he has grown a little too stout,

- Even Matthews is bothered at bowling him out.

- He's our life blood and soul in this noblest of games,

- And yet on our praises he's many more claims;

- No pride, although rich, condescending and free,

- And a well informed man and a city M.P.[17]

The first University Match between Oxford and Cambridge was held at Lord's in 1827,[18] at the instigation of Charles Wordsworth, establishing what would be the oldest first-class fixture in the world until 2020. The ground remained under the ownership of Ward until 1835, after which it was handed over to James Dark. The pavilion was refurbished in 1838, with the addition of gas lighting.[19] Around this time Lord's could still be considered a country ground, with open countryside to the north and west.[20] Lord's was described by Lord Cottesloe in 1845 as being a primitive venue, with low benches put in a circle around the ground at a good distance providing seating for spectators.[21] Improvements to the ground were gradually made, with the introduction of a telegraph scoreboard in 1846. A small room was built on the north side of the pavilion in 1848 for professionals, providing them with a separate entrance to the field. In the same year scorecards were introduced for the first time, from a portable press, and drainage was installed in 1849–50.[21]

The Australian Aboriginal cricket team toured England in 1868, with Lord's hosting one of their matches to a mixed response, with The Times describing the tourists as "a travestie upon cricketing at Lord's" and "the conquered natives of a convict colony". Dark proposed to part with his interest in the ground in 1863, for the fee of £15,000 for the remaining 29+1⁄2 years of his lease. An agreement was reached in 1864, with Dark, who was seriously ill,[22] selling his interests at Lord's for £11,000.[18][6] The landlord of the ground, Isaac Moses, offered to sell it outright for £21,000 in 1865, which was reduced to £18,150. William Nicholson, who was a member of the MCC committee at the time advanced the money on a mortgage, with his proposal for the MCC to buy the ground being unanimously passed at a special general meeting on 2 May 1866.[18] Following the purchase, a number of developments took place. These included the addition of cricket nets for players to practise and the construction of a grandstand designed by the architect Arthur Allom, which was built in the winter of 1867–68 and also provided accommodation for the press.[23][24][25] This was funded by a private syndicate of MCC members, from whom the MCC purchased the stand in 1869.[26] The wicket at Lord's was heavily criticised in the 1860s due to its poor condition, with Frederick Gale suggesting that nine cricket grounds out of ten within 20 miles of London would have a better wicket;[23] the condition was deemed so poor as to be dangerous that Sussex refused to play there in 1864.[11]

Continued developments

By the 1860s and 1870s, the great social occasions of the season were the public schools match between Eton and Harrow, the University Match between Oxford and Cambridge, and the Gentlemen v Players, with all three matches attracting great crowds. Crowds became so large that they encroached on the playing area, which necessitated the introduction of the boundary system in 1866.[27] Further crowd control measures were initiated in 1871, with the introduction of turnstiles.[28] The pavilion was expanded in the mid-1860s and shortly thereafter it was decided to replace the original tavern with a new construction commencing in December 1867.[11] At this time a nascent county game was beginning to take shape.[29] With Lord's hosting more county matches, the pitches subsequently improved with the umpires being responsible for their preparation.[30]

Middlesex County Cricket Club, which had been founded in 1864, began playing their home games at Lord's in 1877 after vacating their ground in Chelsea,[6] which had been considered a serious rival to Lord's given its noblemen backers.[31] In 1873–74, an embankment was constructed which could accommodate 4,000 spectators in four rows of seats. Four years later a new lodge and was constructed to replace an older lodge, along with a new workshop, stables and a store room at a cost of £1,000.[32] To meet the ever increasing demand to accommodate more spectators, a temporary stand was constructed on the eastern side of the ground.[33] After many years of complaints regarding the poor condition of the Lord's pitch, the MCC took action by installing Percy Pearce as Ground Superintendent in 1874. Pearce had previously held the same position at the County Ground, Hove. His appointment vastly improved the condition of the wicket, with The Standard describing them as "faultless".[34]

The Australian cricket team captained by Dave Gregory first visited Lord's on 27 May 1878, defeating their MCC hosts by 9 wickets.[35] This was considered a shock result and established not only the fame of the Australian team, but also the rivalry between England and Australia.[36] Lord's hosted its first Test match during the 1884 Ashes, becoming the third venue in England to host Test cricket after The Oval and Old Trafford.[37] The match was won by England by an innings and 5 runs, with England's A. G. Steel and Edmund Peate recording the first Test century and five wicket haul at Lord's respectively.[38]

As part of the Golden Jubilee Celebrations for Queen Victoria in 1887, the Kings of Belgium, Denmark, Saxony, and Portugal attended Lord's. It was noted that none of them had any grasp of cricket. In the same year Lord's hosted the MCC's hundredth anniversary celebrations, with the MCC playing a celebratory match against England.[39] With only a two-tiered covered grandstand and both increasing membership and spectator numbers, it was decided to build a new pavilion at a cost of £21,000.[25] Construction on this pavilion, which was designed by Thomas Verity, took place in 1889–90.[40] The pavilion it replaced was relocated and painstakingly rebuilt on an estate in Sussex, where it lived out its days as a glorified garden shed.[41] Soon after this, the MCC purchased the land to the east, known today as the Nursery Ground; this had previously been a market garden known as Henderson's Nursery which had grown pineapples and tulips.[40][25][42] The ground was subsequently threatened by the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway's attempts to purchase the area for their line into Marylebone station.[43] After considering the company's offer, the MCC relinquished a strip of land bordering Wellington Road and was given in exchange the Clergy Orphan School to the south.[40] In order to build the railway into Marylebone station, the Nursery Ground had to be dug up to allow tunnels to be constructed between 1894 and 1898 using the cut-and-cover method. Once completed the railway company laid a new pitch.[44]

_(14784598082).jpg.webp)

It was rumoured that subsequent tunnelling under Wellington Road provided the banking for the Mound Stand, which was constructed in 1898/99 on an area previously occupied by tennis and rackets courts. The rapid development of Lord's was not well met by some, with critics suggesting Thomas Lord would 'turn in his grave' at Lord's expansion.[40] 1899 saw Albert Trott hit a six over the pavilion while playing for the MCC against the touring Australians, remaining as of 2024 the only batsman to do so.[45][46] The Imperial Cricket Conference was founded by England, Australia and South Africa in 1909, with Lord's serving as its headquarters.[47]

Lord's hosted three of the nine Test matches in the ill-fated 1912 Triangular Tournament which was organised by the South African millionaire Sir Abe Bailey.[48] The ground's centenary was commemorated in June 1914 with a match between MCC, whose team was selected from the touring party from the recent tour of South Africa, and a Rest of England team. The Rest of England won the three-day match by an innings and 189 runs.[49] Lord's was requisitioned by the army during the First World War, accommodating the Territorial Army, Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) and Royal Army Service Corps. Both cooking and wireless instruction classes were held at the ground for military personnel. Once the RAMC departed, the War Office used the Nursery Ground and other buildings as a training centre for Royal Artillery cadets. The pavilion and its long room were used throughout the war for the manufacture of hay nets for horses on the Western Front.[50] Though requisitioned, Lord's held several charity cricket matches during the war, featuring military teams from the various territories of the British Empire.[51] These matches were well attended and one such match in 1918 between England and the Dominions was attended by George V and the Duke of Connaught.[52]

Inter–war years and WWII

First-class cricket returned to Lord's in 1919, with a series of two-day matches in the County Championship.[53] 1923 saw the installation of the Grace Gates, a tribute to W. G. Grace who had died in 1915.[54] They were inaugurated by Sir Stanley Jackson, who had suggested the inclusion of the words THE GREAT CRICKETER in the dedication.[55] These gates replaced an earlier, less decorative, entrance to the ground. With attendances growing in number, it was suggested that Lord's aim to accommodate crowds of up to 40,000 for Test matches; however, the stands at the ground were considered inadequate with the grandstand described as "hopelessly out of date".[56] To accommodate these crowds, the old grandstand was demolished and a new one was built in its place in 1926, designed by the architect Sir Herbert Baker. Completion of the stand was delayed due to the 1926 General Strike.[26] Upon its completion, Baker presented Lord's with a weather vane Father Time removing the bails from a wicket, which was placed on top of the grandstand. The full weathervane is 6 ft 6 in (1.98 m) tall, with the figure of Father Time standing at 5 ft 4 in (1.63 m). Baker further contributed to the landscape of Lord's by designing the Q Stand next to the pavilion in 1934, while at the Nursery End stands were also erected. Careful consideration was taken to preserve the treeline dividing the main ground from the Nursery Ground.[47] The West Indies under the captaincy of Karl Nunes played their first Test match at Lord's in 1928.[57] The ground later hosted the first televised Test match during the Second Test of the 1938 Ashes series.[25]

The 1935 season saw the Lord's pitches badly affected by crane fly larvae, known as leatherjackets. The larvae caused bald patches to appear on the playing surface and had to be removed by the ground staff, although spin bowlers did gain some benefit from the bare patches.[58]

In contrast to the First World War, Lord's was not requisitioned by the military during the Second World War. Lord's hosted matches throughout the war for the London Counties cricket team, amongst others, which attracted large crowds. The ground was spared major damage from The Blitz. An oil bomb landed in the Nursery Ground in 1940, with a high-explosive bomb also narrowly missing the Nursery End stands in December of the same year. The grandstand and the pavilion were hit by incendiary bombs, damaging their roofs. The in-house Lord's firefighters reacted quickly and limited the damage. As the war progressed, the threat came not from the Luftwaffe but the newly developed V-1 flying bomb. Lord's had several near misses from these weapons in 1944, with one bomb landing 200 yards (180 m) short of the ground near to Regents Park.[59] The Nursery Ground had been requisitioned by the Royal Air Force and converted into a barrage balloon site.[47][60] The most high-profile damage during the war was that to Father Time, which was damaged by a one such balloon which had broken loose and drifted toward the grandstand, catching Father Time and depositing it into the seating at the front of the stand. International cricket resumed at the end of the war, with Lord's hosting one of the Victory Tests (though the matches did not actually have Test status) between the Australian Services cricket team and England.[59]

Post–war years

Following the end of the war attendances at cricket matches grew. The gross attendance of 132,000 and the gate receipts of £43,000 for the Second Test of the 1948 Ashes series was a record for a Test match in England at that time.[61] This demand necessitated further expansion of the ground, with the construction of the Warner Stand in 1958, which included snack bars and a press box.[47][25] This stand was the work of the architect Kenneth Peacock and replaced an area of raised ground lined with trees from where it was traditionally possible to watch a match from the comfort of ones own carriage. Prior to the construction of the Warner Stand, all stands at the ground were identified by letters of the alphabet.[62]

The record numbers of spectators who attended Test and County Championship matches began to decline by the end of the 1950s and cricket in England found itself from a position of 2.2 million paid County Championship spectators in 1947, dropping to 719,661 in 1963. To arrest this decline, List A one-day cricket was introduced in 1963, with Lord's hosting its first List A match in the 1963 Gillette Cup between Middlesex and Northamptonshire and later hosted the final of the competition between Sussex and Worcestershire in front of a sell-out 24,000 crowd. It was the first such final held anywhere in the world.[63] The tavern and its adjoining buildings were demolished in 1968 to make way for the construction of the Tavern Stand, again designed by Peacock.[25] The tavern was subsequently re-sited next to the Grace Gates and was complemented with a banqueting hall.[47] Lord's hosted its first One Day International (ODI) in 1972,[64] with Australia defeating England by 5 wickets.[65] Three years later Lord's hosted the final of the inaugural men's World Cup, with the West Indies triumphing over Australia.[66] Four years later, Lord's held the final of the 1979 World Cup, with the West Indies once against triumphing, this time against England.[67]

The first women's cricket match at Lord's took place in August 1976 when England and Australia played a 60-over ODI which England won by eight wickets. The opportunity to play a women's match at Lord's resulted from a campaign by Rachael Heyhoe Flint, and was given extra impetus by England's victory in the 1973 Women's Cricket World Cup. England had to wait another 11 years to play their second match at Lord's.[68] The ground hosted the final of the ICC Women's Cricket World Cup in 1993 with England beating New Zealand to win the World Cup. The ground was not fully opened for the game and only 5,000 spectators were able to attend.[69]

A new indoor cricket school was completed in 1973 at the Nursery End, funded by £75,000 from Sir Jack Hayward and additional funds raised by the Lord's Taverners and The Sports Council.[70] The West Indies appeared in their third successive World Cup final in 1983, but were defeated by 43 runs by India.[71] The Mound Stand was demolished in 1985 to make way for a new stand designed by Michael Hopkins and Partners, which opened in time for the MCC's bicentenary in 1987.[72] That bicentenary was celebrated with a five-day match between MCC and a Rest of the World team in August 1987, which ended in a draw after the final day was rained off.[73]

Graham Gooch made the first Test match triple-century at Lord's, scoring 333 against India in 1990.[74] The final decade of the 20th–century saw rapid redevelopment of Lord's. The Compton and Edrich stands were completed in 1991, having run over time and budget.[25] The indoor school closed in 1994, owing to the construction of a new state-of-the-art indoor cricket centre which opened in 1995.[70] The old grandstand was demolished in 1996, with a replacement designed by Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners being completed in 1998. Since 1997, Lord's has been home to the European Cricket Council (ECC), which administers cricket outside of the European full-member nations.[75] With Lord's hosting three matches in the 1999 World Cup, including the final, the MCC set about improving press facilities by constructing the Media Centre at the Nursery End between the Compton and Edrich stands, offering commanding views towards the pavilion from over the bowlers arm. The Media Centre was opened in April 1999 by then MCC President Tony Lewis.[76]

21st–century developments

Lord's hosted its one-hundredth Test match in June 2000, with England defeating the West Indies by two wickets; the match was also notable for the 21 wickets which fell on the second day, the most to fall in a day in a Test at Lord's since 1888.[77] The ground also hosted The University Match over three days for the last time in 2000, after which the match alternated between Fenner's at Cambridge and University Parks at Oxford.[78] The fixture has continued at Lord's since 2001 as a one-day limited overs match.[79] At the start of the 21st–century, the Lord's slope which provides a benefit to both seam bowlers and swing bowlers from the Pavilion and Nursery Ends respectively, was under threat of being levelled due to the advent of drop-in pitches.[80] However, the MCC resisted these calls as levelling the pitch would require the rebuilding of Lord's and would mean Test cricket would not be able to be played there for five years. The outfield was notorious for becoming waterlogged due to the clay soil, which resulted in considerable lost match time. The entire outfield was relaid in the winter of 2002 with the clay soil being replaced with sand, which has improved drainage.[81] Lord's hosted its first Twenty20 match in the second edition of the Twenty20 Cup in 2004.[82] In 2005 the International Cricket Council (formerly the Imperial Cricket Conference) headquarters, which had been located at Lord's since its foundation in 1909,[83] were closed and moved to the Dubai Sports City in the United Arab Emirates.[84]

Temporary floodlights were installed at the ground in 2007, but were removed in 2008 after complaints of light pollution from local residents. In January 2009, Westminster City Council approved the use of new 48 metre high retractable floodlights designed to minimise light spillage into nearby homes. Conditions of the approval included a five-year trial period during which up to 12 matches and 4 practice matches could be played under the lights from April to September. The lights must be dimmed to half-strength at 9.50 pm and be switched off by 11 pm. The floodlights were first used successfully on 27 May 2009 during the Twenty20 Cup match between Middlesex and Kent.[85] Two weeks after the first use of the floodlights, Lord's hosted its first Twenty20 International in the World Twenty20 between England and the Netherlands, which resulted in a shock last-ball win for the associate nation.[86] Lord's held the final of the competition between Pakistan and Sri Lanka, which Pakistan won by 8 wickets.[87]

In 2008 plans were drawn up by the MCC committee to fund the future £250 million development of the ground by constructing residential apartments and a luxury hotel along the Wellington Road and Grove End Road.[88]

The Lord's Masterplan was unveiled in 2013, which is a twenty-year plan to redevelop the ground and improve its facilities. The first phase of the masterplan involved the demolition and replacement of the Warner Stand with a new stand, which was built between 2015 and 2017. The new stand has improved facilities for match officials and reduced the number of restricted view spectator seats from 600 to 100.[89] Phase two of the masterplan involved the demolition of the Compton and Edrich Stands in 2019, with their replacements being completed in 2021; these provided an extra 2,000 seats and for the first time were linked by a walkway bridge.[89]

Lord's celebrated the two hundredth anniversary of its current ground in 2014. To mark the occasion, an MCC XI captained by Sachin Tendulkar played a Rest of the World XI led by Shane Warne in a 50-over match.[90]

Two matches of note were played at the ground in July 2019. The first of these was 2019 World Cup Final between England and New Zealand, which ended as a tie with both sides making 241 runs from their 50 overs. The final was then decided by a Super Over, which also ended in a tie. Therefore, the winner was decided on the number of boundaries scored in the game and Super Over; this was England's first World Cup triumph.[91] A second match of note followed four days later when Ireland played their first Test match at Lord's, where they bowled England out for 85 on the first morning of the match with Tim Murtagh taking 5 for 13. Despite this, in their second innings Ireland were dismissed for 38, the lowest Test total at Lord's and lost the match by 143 runs.[92]

In August 2022 the ground's East Gate was renamed the Heyhoe Flint Gate in honour of Rachael Heyhoe Flint.[93]

Ground features and facilities

Stands

As of 2024, the stands at Lord's are (clockwise from the Pavilion):[94]

Warner Stand

Warner Stand Grand Stand

Grand Stand Compton Stand

Compton Stand Edrich Stand

Edrich Stand Mound Stand (left)

Mound Stand (left)_01.jpg.webp) Tavern Stand

Tavern Stand Allen Stand (right) (formerly Q Stand)

Allen Stand (right) (formerly Q Stand) Overview of the stands at Lord's

Overview of the stands at Lord's

Many of the stands were rebuilt in the late 20th century. In 1987 the new Mound Stand, designed by Michael Hopkins and Partners, was opened, followed by the Grand Stand, designed by Nicholas Grimshaw, in 1996.[95] The Media Centre, opposite the Pavilion between the Compton and Edrich Stands, was added in 1999. Designed by Future Systems, it won the Royal Institute of British Architects' Stirling Prize for 1999.[96] The redevelopment of the Compton Stand and Edrich Stands was completed in 2021, adding 2,600 seats and bringing the ground capacity to 31,100 spectators.[97] The two ends of the pitch are the Pavilion End (south-west), where the main members' pavilion is located, and the Nursery End (north-east), dominated by the Media Centre.[94]

The current Grand Stand replaced the one built in 1926 by Sir Herbert Baker. Although the stand was described as "truly a thing of beauty, loved by all who gazed upon it", it did have limitations for spectators. 43% of the seats had an obstructed views of the playing area and the structure itself was becoming rotten.

Pavilion

The current pavilion at Lord's is the third pavilion to stand at the ground and is the main survivor from the Victorian era, having been built in 1889–90. It has been a Grade II* listed building since September 1982.[98] The pavilion was constructed using brick with ornate terracotta facing, which includes terracotta gargoyles, such as 'The Patriarch' which is thought to represent Lord Harris.[99] The building consists of a long, two storey centre section with covered seating between two end towers which are capped with pyramidal roofs which have ornate wrought and cast iron lanterns.[98] Running the full length of the rear of the second floor is the pavilion roof terrace, which provides views of the entire ground.[100] It underwent an £8 million refurbishment programme in 2004–05. The pavilion is primarily for members of the MCC, who may use its amenities, which include seats for viewing the cricket, the Long Room and its Bar, the Bowlers Bar, and a members' shop. At Middlesex matches the pavilion is open to members of the Middlesex County Cricket Club. The Pavilion also contains the dressing rooms where players change, each of which has a small balcony for players to watch the play.

The Long Room is found on the ground floor of the pavilion and has been described by Lawrence Booth as "the most evocative four walls in world cricket".[101] Players walk through the Long Room on their way from the dressing rooms to the cricket field; this walk is notoriously long and complex at Lord's. On his Test debut in 1975, David Steele got lost on his way out to bat "and ended up in the pavilion's basement toilets".[102] Once a player reaches the Long Room is approximately 30 paces from the swing door at the rear of the room to the steps which lead onto the playing field.[103] The Long Room is decorated with paintings of famous cricketers and administrators from the 18th to the 21st century, predominantly English players. For an overseas player to have their portrait placed in the Long Room is a considerable honour. Amongst overseas players to have a portrait in the Long Room are four Australians: Don Bradman, Keith Miller, Victor Trumper and Shane Warne.[104]

.jpg.webp)

Found in the players dressing rooms are the honours boards for commemorating centuries, five wicket hauls and ten wicket hauls in a match. Two honours boards for batting and bowling commemorate England players in the home dressing room,[105] while the batting and bowling boards commemorating players from other nationalities are found in the away dressing room.[106] Originally only these achievements in Test matches were commemorated, but since 2019 an honours board for ODIs has been introduced.[107] As of 2024 167 players have made 240 Test centuries at Lord's and 130 players have taken 186 five wicket hauls. In ODI's 29 players have made 32 centuries at Lord's and 14 players have taken a five wicket haul. A separate "neutral" honours board was created in 2010 to coincide with Lord's hosting a Test match between Australia and Pakistan. The Australians Warren Bardsley and Charlie Kelleway were the first two names added to this board, commemorating their centuries against South Africa in 1912. They were joined by the Australians Shane Watson and Marcus North, who both took five wicket hauls against Pakistan.[108]

The dress code in the pavilion is notoriously strict. Men are required to wear "ties and tailored coats and acceptable trousers with appropriate shoes" and women are required to wear "dresses; or skirts or trousers worn with blouses, and appropriate shoes".[109] Until 1999 women – except Queen Elizabeth II – were not permitted to enter the pavilion as members during play, due to the gender-based membership policy of the MCC.[110][111] The 1998 decision to allow female MCC members represented a historic modernisation of the pavilion and its clubs.[112]

Media Centre

The decision to build the Media Centre was made during a meeting of the MCC committee in 1995.[113] These plans sought to remove the inadequate media facilities mostly concentrated in the Warner Stand which could accommodate 90 journalists, along with wooden shacks dotted around the ground for commentators,[114] and replace them with a new purpose built facility. It was then approved by members of the MCC at a special general meeting in December 1996.[113] A gap between the Compton and Edrich Stands was selected, with space limitations requiring the centre to stand 15 metres (49 ft) above the ground on reinforced supports from the structure around its two lift shafts. This design allowed for uninterrupted access between the main ground and the Nursery Ground, while also allowing the movement of ground staff and their equipment.[113]

It was designed by the Future Systems architectural practice led by Czech architect Jan Kaplický and was the first all-aluminium, semi-monocoque building in the world, costing about £5 million. Construction began in January 1997 and was completed in time for the 1999 World Cup. It was built in 32 sections and fitted out by Pendennis Shipyard in Falmouth in combination with Centraalstaal from the Netherlands.[115] These pieces were then delivered to Lord's where they were lowered into place during the 1998 season.[113] The glazing on the front of the centre is inclined 25° so as to eliminate reflections and glare on the pitch to minimise the visual barrier between members of the media and the players. The lower tier of the centre provides accommodation for 118 journalists, with two hospitality boxes either side which accommodate 18 people each. The top tier has radio and television commentary boxes, consisting of two television studios, two large commentary and radio commentary boxes, each holding up to six people.[114] The centre's only opening window is in the broadcasting box used by BBC Test Match Special.[116] The building won eight architectural awards, including the RIBA Stirling Prize for architecture in 1999. The Media Centre was originally sponsored by NatWest, with sponsorship being taken over by Investec in 2007. Since 31 May 2011, the media centre has been sponsored by J. P. Morgan.[117]

Nursery Ground

Purchased in two parts by the MCC in 1838 and 1887, the ground is primarily used as a practice ground and is considered to have some of the best grass nets in the world.[118] In 1895 the Middlesex Volunteers requested the use of the Nursery Ground as a drill ground, but this was declined by the MCC.[119] The Nursery Pavilion, which was constructed in 1999, overlooks the playing area of the Nursery Ground and is one of London's largest venues.[120] The ground has hosted one first-class cricket match in 1903, when the MCC played Yorkshire;[121] the match was originally to be played on the main Lord's ground, but heavy rain had fallen and in the week leading up to the match this had led to the abandonment of a match between the MCC and Nottinghamshire. The heavy rain persisted during the MCC v Yorkshire match, with the players spending the first two days of the three-day match sat in the pavilion. However, it was deemed that the playing surface on the Nursery Ground was suitable for the third day of the match to be played there,[122] with both sides batting for an innings each and Yorkshire's Wilfred Rhodes making an unbeaten 98.[123]

The Women's University Match has been played on the Nursery Ground since 2001,[124] however following calls for gender equality, the 20-over fixture will be played on the main Lord's ground for the first time from 2022 alongside the men's fixtures.[125] On big match days crowds are allowed onto the outfield. The Cross Arrows Cricket Club play their home matches at the Nursery Ground toward the end of the cricket season.[118] The construction of the new Compton and Edrich stands, beginning in August 2019, encroached on the Nursery Ground's playing area. In order to reclaim the playing area lost to the redevelopment of the stands, the temporary Nursery Pavilion will be demolished in 2025–26 and the playing area will be extended up to the perimeter wall running along the Wellington Road.[126]

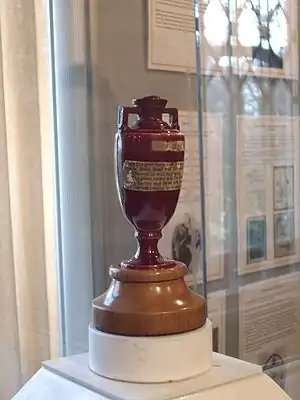

MCC Museum and Library

Lord's is the home of the MCC Museum, which is the oldest sports museum in the world, and contains the world's most celebrated collection of cricket memorabilia, including The Ashes urn.[127] MCC has been collecting memorabilia since 1864, the collection being originated by Sir Spencer Ponsonby-Fane, who subsequently became the club Treasurer.[128] These items were originally displayed in the pavilion, limiting access to the collection to MCC members. Following the Second World War the collection had outgrown its home in the pavilion, with a decision made to relocate the collection and open it to the public. The MCC moved the collection to a disused rackets court, which had fallen into disrepair during the war, with this location also acting as a memorial to the fallen members of the MCC from the two world wars.[129] They appointed Diana Rait Kerr, "to whom the game owes a great debt", to be the first full-time creator of the museum and library, a position she held from 1945 to 1968.[128] The museum was officially opened to the public as the Imperial Memorial Collection by the Duke of Edinburgh in 1953. During her tenure as curator, Rait Kerr secured donations of pictures, equipment and other artefacts from around the world.[129] Rait Kerr was succeeded as curator by Stephen Green in 1968.[128] The museum today welcomes around 50,000 visitors per year.[129]

Amongst the items on display include cricket kit used by Victor Trumper, Jack Hobbs, Don Bradman, Shane Warne, and others; many items related to the career of W. G. Grace; and curiosities such as the stuffed sparrow that was 'bowled out' by Jahangir Khan of Cambridge University in delivering a ball to T. N. Pearce batting for the MCC on 3 July 1936. It also contains the battered copy of Wisden that helped to sustain E. W. Swanton through his captivity in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp during the Second World War. It continues to collect historic artefacts and also commissions new paintings and photography.[129] It contains the Brian Johnston Memorial Theatre, a cinema which screens historical cricket footage for visitors. The museum collaborates with a number of national museums and schools through active loans, in addition to community and tour programmes. It is a member of the Sporting Heritage network.[127]

Lord's also has one of the largest and most comprehensive collections of books and publications dedicated to cricket. The library includes over 20,000 volumes and grows by around 400 volumes a year. The library encourages donations from authors and publishers. The library operates as a private library for MCC members on match days, but is open by appointment on non-match days.[127] It was expanded in the 1980s with the opening of a new library in the tennis court block to the rear of the pavilion,[130] having previously been housed in a small office in the pavilion.[131] In 2010, a selection of 100 duplicates from the library's collection was offered for auction by Christie's with proceeds going to support the library.[132]

Gardens

Lord's has two gardens, the Harris Garden and the Coronation Garden. The Coronation Garden was created behind the A stand (Warner Stand) in 1952 to celebrate the Coronation of Elizabeth II.[133] It contains weeping Ash trees and other trees, providing a shaded area under which benches are found. Preserved in the Coronation Garden is one of the first models of mass-produced, cast iron, heavy rollers dating from the 1880s, which was in use at Lord's until 1945.[134] A large bronze statue of W. G. Grace stands in the Coronation Garden. The garden is popular with picnickers during major matchdays.[135] The Harris Garden, formerly tennis courts, was created as a rose garden in 1934 in memory of Lord Harris.[136][137] The garden was restored and re-launched in 2018. The restoration included the exposing of the flint wall which runs along the back of the garden,[138] which displays a dedication to Lord Harris. The flower beds in the Harris Garden were replanted in 2018 with a floral design featuring flowers from all the Test playing nations.[139] The Harris Garden is available for private hire and can host up to 300 people.[140][138]

Other sports

Pelham Warner was of the opinion that the only other sport which had any real standing at Lord's was real tennis.[141] A real tennis court began construction in October 1838, with the foundation stone of the court being laid by Benjamin Aislabie.[142] The court was built at a cost of £4,000, which at the time was exceptionally high.[143] A real tennis competition was later established in 1867.[142] The tennis court was demolished in 1898 to make way for the Mound Stand, with a replacement court being built behind the pavilion in 1900 in the back garden of number 3 Grove End Road. By 2005 the MCC had a real tennis playing membership of 200.[144] The playing of rackets at Lord's dates from 1844 and is currently played in the same building as real tennis.[142] Lord's hosted the Public Schools Championship in 1866, with Harrow School triumphing. Since then the Championship has been held at Prince's Club, before moving to Queen's Club.[141]

With the advent of lawn tennis, a decision was made at the annual general meeting of the MCC in May 1875 to construct a tennis court, although there was strong opposition from some members.[145] A suggestion to standardise the rules of tennis was made at Lord's by J. M. Heathcote, who was himself a prominent real tennis player. On 3 March 1875 the MCC, in its capacity as the governing body for rackets and real tennis, convened a meeting at Lord's to test the various versions of lawn tennis which existed with the aim to fully standardise the game's rules.[146] Amongst the various versions of lawn tennis which were demonstrated were Major Clopton Wingfield's Sphairistikè, and John H. Hale's Germains Lawn Tennis.[147] After the meeting, the MCC Tennis Committee was tasked with framing the rules. On 29 May 1875 the MCC issued the Laws of Lawn Tennis, the first unified rules for lawn tennis, which were adopted by the club on 24 June.[148][149] These rules were amended by the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club for the 1877 Wimbledon Championship, with the dimensions of the tennis courts being based on those at Lord's; the courts on which these were based are no longer used for tennis and are now part of the Harris Garden.[150][151]

The original intention for the purchase of the northern part of the Nursery Ground in 1838 was for it to serve as an archery venue.[152] Archery is recorded as having been played at Lord's as far back as August 1844, when visiting Ioway Indians camped at Lord's and demonstrated their archery skills.[153] Lord's was one of the venues for the 2012 Summer Olympics, hosting the archery competition.[154] The archery competition took place in front of the pavilion, which the archers were positioned in front of, with the targets placed 70 metres away just past the square and in front of the Media Centre. Either side of the square temporary stands holding up to 5,000 spectators were erected.[155]

Lacrosse was first played at Lord's in 1833 by the Canadian pioneers of the sport.[156] Lacrosse returned to Lord's in 1876, when a team of Canadian Gentlemen Amateurs led by William George Beers played an exhibition match at the ground against a team of Iroquois Indians.[157] A Canadian lacrosse team toured the United Kingdom again in 1883, with one exhibition match being staged at Lord's in front of several thousand spectators.[158] It was later played again at Lord's in October 1953 when the Kenton and Old Thorntonians lacrosse clubs met there in a lacrosse championship match, with further fixtures following in November of the same year.[156]

Baseball was first played at Lord's in 1874 when the MCC hosted a touring party of 22 baseball players from the Boston Red Stockings and the Philadelphia Athletics, who were the two leading American baseball teams of the time.[159][160] The Red Stockings defeated The Athletics 24–7 in front of a crowd of 5,000 spectators.[161] A baseball game was held at Lord's during the First World War to raise funds for the Canadian Widows and Orphans Fund. A Canadian team played a team of American London residents in a match watched by 10,000 people.[162][163]

Lord's hosted the London pre-1968 Olympics field hockey tournament in 1967.[164] One match saw India play Pakistan, which was broadcast live on the BBC, which at the time was unprecedented in field hockey.[165] Pakistan won the match 1–0,[166] while Pakistan also went on to defeat Belgium later in the tournament.[167] The ground hosted further international hockey matches in the 1970s.[164] The University Match between Oxford and Cambridge hockey clubs took place at Lord's for twenty-one years beginning in 1969.[168] England beat world-champions India for the time ever in this venue, in 1978.[169]

Other sports to have been played at Lord's include lawn bowls and billiards. In 1838,[170] a bowling green was constructed at the western end of the ground, in addition to a billiards room with two billiard tables which was added to the original tavern,[170][22][119] with professional billiards players playing matches at Lord's on a Monday during the cricket season;[141] In the late 1840s and early 1850s, Lord's held Galloway pony races after the cricket season was over, with races starting at the tavern and finishing twenty yards south of the pavilion.[171]

International records

Test

- Highest team total: 729/6 declared by Australia v England, 1930[172]

- Lowest team total: 38 all out by Ireland v England, 2019[173]

- Highest individual innings: 333 by Graham Gooch for England v India, 1990[174]

- Best bowling in an innings: 8/34 by Ian Botham for England v Pakistan, 1978[175]

- Best bowling in a match: 16/137 by Bob Massie for Australia v England, 1972[176]

One Day International

- Highest team total: 334/4 (60 overs) by England v India, 1975[177]

- Lowest team total: 107 all out (32.1 overs) by South Africa v England, 2003[178]

- Highest individual innings: 138* by Viv Richards for West Indies v England, 1979[179]

- Best bowling in an innings: 6/24 by Reece Topley for England v India, 2022[180]

Twenty20 International

- Highest team total: 199/4 (20 overs) by West Indies v ICC World XI, 2018[181]

- Lowest team total: 93 all out (17.3 overs) by Netherlands v Pakistan, 2009[182]

- Highest individual innings: 78 by Mahela Jayawardene for Sri Lanka v Ireland, 2009[183]

- Best bowling in an innings: 4/11 by Shahid Afridi for Pakistan v Netherlands, 2009[184]

All records correct as of 8 January 2024.

Domestic records

First-class

- Highest team total: 645/6 declared by Durham v Middlesex, 2002[185]

- Lowest team total: 15 by MCC v Surrey, 1839[186]

- Highest individual innings: 316* by Jack Hobbs for Surrey v Middlesex, 1926[187]

- Three bowlers have taken a ten-wicket haul in an innings where the exact bowling figures are not recorded, however it is known they conceded less than 20 runs, they are William Lillywhite, Edmund Hinkly and John Wisden. The best bowling figures in an innings where the records are complete is Samuel Butler's 10 for 38 for Oxford University v Cambridge University in 1871.[188]

- William Lillywhite has taken the most wickets in a match, with 18 for the Players v Gentlemen in the Gentlemen v Players fixture of 1837, though his exact bowling figures are not recorded.[189]

List A

- Highest team total: 368/2 (50 overs) by Nottinghamshire v Middlesex, 2014[190]

- Lowest team total: 57 (27.2 overs) by Essex v Lancashire, 1996[191]

- Highest individual innings: 187* by Alex Hales for Nottinghamshire v Surrey, 2017[192]

- Best bowling in an innings: 7/22 by Jeff Thomson for Middlesex v Hampshire, 1981[193]

Twenty20

- Highest team total: 223/7 (20 overs) by Surrey v Middlesex, 2021[194]

- Lowest team total: 90 (14.4 overs) by Kent v Middlesex, 2015[195]

- Highest individual innings: 102 not out by Stephen Eskinazi for Middlesex v Essex, 2021[196]

- Best bowling in an innings: 6/24 by Tim Murtagh for Surrey v Middlesex, 2005[197]

All records correct as of 8 January 2024.

References

- ↑ "Lord's cleared to have full capacity for England-Pakistan ODI". The Cricket Paper. 2 July 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ↑ "Lord's". Cricinfo. Archived from the original on 11 September 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ↑ see MCC museum Archived 12 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine webpage

- ↑ Warner 1946, p. 17–18.

- 1 2 3 4 Barker, Philip (2014). Lord's Firsts. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445633299.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Powell, William (1989). The Wisden Guides To Cricket Grounds. London: Stanley Paul & Co. Ltd. pp. 14–7. ISBN 009173830X.

- 1 2 Warner 1946, p. 18.

- ↑ Eyres, Harry (18 July 2009). "Grounded on terra firma". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ↑ Levison, Brian (2016). Remarkable Cricket Grounds. London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 9781911216599.

- ↑ Warner 1946, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Green 2010, p. 46

- ↑ Warner, Pelham (1987) [First published 1946]. Lord's 1787–1945. London: Pavllion Books. p. 28. ISBN 1851451129.

- ↑ "First-Class Matches played on Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ↑ Altham 1962, p. 67.

- ↑ Green, Benny (1987). The Lord's Companion. London: Pavilion Books. p. 7. ISBN 1851451323.

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 31

- ↑ Harris, 4th Baron Harris, George; Ashley-Cooper, A. S. (1920). Lord's and the M. C. C.: A Cricket Chronicle of 137 Years. H. Jenkins Limited. p. 48.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 Green 2010, p. 7

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 35

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 37

- 1 2 Green 2010, p. 41

- 1 2 Green 2010, p. 44

- 1 2 Green 2010, p. 45

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 51

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Lord's – A brief timeline". ESPNcricinfo. 3 May 2005. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- 1 2 "The New Grand Stand is completed". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ Green 2010, pp. 57–8

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 59

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 52

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 60

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 78

- ↑ Green 2010, pp. 59–60

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 63

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 76

- ↑ "Marylebone Cricket Club v Australians, 1878". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 27 May 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ↑ Green 2010, pp. 81–4

- ↑ Powell 1989, pp. 14–5

- ↑ "England v Australia, 1884". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ↑ Green 2010, pp. 94–5

- 1 2 3 4 Powell 1989, p. 15

- ↑ "Thomas Verity's new Pavilion is completed". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ Baker 2014, p. 129

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 132

- ↑ Wilson, Bill (8 August 2018). "Battle over rail tunnels at Lord's cricket ground rumbles on". BBC News. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 162–3

- ↑ Williamson, Martin (19 June 2010). "Albert Trott's mighty hit". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Powell 1989, p. 16

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 190

- ↑ Warner 1987, pp. 169–170

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 193-4

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 193-206

- ↑ Warner 1987, p. 171

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 207

- ↑ Historic England (7 February 1996). "Grace Gates at Lord's Cricket Ground (1246985)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ Midwinter 1981, p. 154.

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 214

- ↑ Warner 1987, p. 195

- ↑ "Cranefly". Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- 1 2 Williamson, Martin (6 May 2006). "Lord's under attack". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ↑ Warner 1987, p. 245

- ↑ Hayter, R. J. (1949). "Second Test Match England v Australia". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. Wisden. Archived from the original on 10 August 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ↑ "The New Warner Stand is opened". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ↑ Williamson, Martin (20 April 2013). "Opening Pandora's one-day box". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 21 February 2023. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ↑ "ODI Matches played on Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "England v Australia, Prudential Trophy 1972 (2nd ODI)". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ Cozier, Tony. "West Indies victory heralds a new era". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ Cozier, Tony. "England v West Indies". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ Thompson, Jenny (14 July 2005). "Storming cricket's bastion". Espncricinfo. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ Williamson, Martin (20 March 2009). "When women took over Lord's". Espncricinfo. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- 1 2 "First Indoor School at Lord's opened". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "India defy the odds". ESPNcricinfo. 2 June 2008. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 448

- ↑ "MCC v Rest of the World, Lord's, August 20–25 1987". ESPNcricinfo. 7 July 2005. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ↑ "Graham Gooch scores 333". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "From Iceland to Azerbaijan". BBC Sport. 1 February 2002. Archived from the original on 16 February 2004. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ↑ "The 20th anniversary of the Media Centre". www.lords.org. 27 April 2019. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ↑ "England beat West Indies in 100th Lord's Test". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ↑ "Cricket: Varsity game may switch from Lord's". Oxford Mail. 7 July 2000. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ↑ "Cricket: Lord's Varsity to be one-day". Oxford Mail. 24 July 2000. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ Briggs, Simon (19 May 2001). "Slope's future in balance". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ Saltman, David (27 November 2003). "Mallinsons win BALI Principal Award". www.pitchcare.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's admits Twenty20 Cup". BBC Sport. 2 December 2003. Archived from the original on 9 May 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ "ICC ponders Lord's move". BBC Sport. 4 March 2004. Archived from the original on 3 June 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ "Cricket chiefs move base to Dubai". BBC Sport. 7 March 2005. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's floodlights just 'isn't cricket'". Get West London. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ↑ McGlashan, Andrew (5 June 2009). "de Grooth leads Netherlands to famous win". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ↑ Smyth, Rob (21 June 2009). "Pakistan v Sri Lanka – as it happened". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "New housing set to pay for £250m redeveloped Lord's". Ham & High. 4 July 2008. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- 1 2 "The Masterplan". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Sachin Tendulkar and Rahul Dravid re-unite; to face off against Shane Warne again". Yahoo! Cricket. 6 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014.

- ↑ Gardner, Alan. "Epic final tied, Super Over tied, England win World Cup on boundary count". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Chris Woakes and Stuart Broad wreck Ireland dream in a session". ESPNcricinfo. 26 July 2019. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ↑ "Lord's gate dedicated to cricket captain Rachael Heyhoe Flint unveiled". BBC News. 17 August 2022. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- 1 2 "Lord's Ground" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ "Lord's milestones". Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ "LORD'S MEDIA CENTRE (1999)". Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ Tennant I (2021) Bitter feud over expansion of Lord's stands revealed Archived 27 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Times, 26 May 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021. (subscription required)

- 1 2 Historic England. "The Pavilion at Lord's Cricket Ground (1235992)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ Meredith, Anthony (2012). Lords Through Time. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-1445611341. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ↑ "Pavilion Roof Terrace". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ Arm-Ball to Zooter, Lawrence Booth, Penguin 2006, ISBN 0-14-051581-X, p.150-1

- ↑ Bateman, Colin (1993). If The Cap Fits. Tony Williams Publications. p. 155. ISBN 1-869833-21-X.

- ↑ Smith, Ed (2013). Luck: A Fresh Look at Fortune. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 9781408830604. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ↑ Selvey, Mike (12 October 2004). "Obituary: Keith Miller". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ Wilson, Andy (17 May 2012). "Stuart Broad says joining Lord's bowling elite is a 'huge honour'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ Selvey, Mike (20 May 2012). "First Test day four report". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ Hoult, Nick (26 February 2019). "Lord's to honour women's achievements for first time as new board is added for ODIs". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ "Aussies get on honour board at Lord's". Sydney Morning Herald. 13 April 2010. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ Alderson, Andrew (9 December 2007). "MCC's Brearley wants relaxed dress for Lord's". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ↑ "Modernisers stumped in MCC vote". BBC News. 24 February 1998. Archived from the original on 19 October 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ "MCC delivers first 10 maidens". BBC News. 16 March 1999. Archived from the original on 19 July 2004. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's and ladies?". BBC News. 28 September 1998. Archived from the original on 8 November 2002. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "The 20th anniversary of the Media Centre". www.lords.org. 29 April 2019. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- 1 2 Nicholson, Matthew (2007). Sport and the Media. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis. p. 115. ISBN 978-1136364976.

- ↑ "Winner Building Sponsored by BSI NatWest Media Centre, Lord's Cricket Ground, London NW8". www.newcivilengineer.com. 21 October 1999. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ Alexander, Gus. "The Lord's test | Magazine Features". www.building.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ "New Media Centre sponsor: JP Morgan". www.lords.org. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Lord's Nursery Ground". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- 1 2 Green 2010, p. 36

- ↑ "Nursery Pavilion". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ "First-Class Matches played on Lord's Nursery Ground, St John's Wood". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ↑ Barker 2014, p. 129

- ↑ "Marylebone Cricket Club v Yorkshire, 1903". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "Varsity cricket – a one-day wonder?". www.cam.ac.uk. 6 June 2001. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ↑ Dobell, George (21 May 2021). "Women's Varsity match set for full Lord's debut after universities reach agreement". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ↑ "The Future of Lord's". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 "MCC Museum". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 Barclay's World of Cricket – 2nd Edition, 1980, Collins Publishers, ISBN 0-00-216349-7, p47

- 1 2 3 4 "HRH The Duke of Edinburgh opens the MCC Museum". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ↑ Meredith 2012, p. 47

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 436

- ↑ "Release: Christie's to offer a selection of items from the MCC collections". www.christies.com. 21 October 2010. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ↑ Peebles, Ian; Rait Kerr, Diana (1987). Lord's 1946-1970. London: Pavilion Books. p. 78. ISBN 1851451412. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ↑ Evans, Roger D. C. (1991). Cricket Grounds: The Evolution, Maintenance and Construction of Natural Turf Cricket Tables and Outfields. Bingley: Sports Turf Research Institute. p. 15. ISBN 1873431007. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ↑ Hughes, Simon (2010). And God Created Cricket. Ealing: Transworld. p. 89. ISBN 9781446422472. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ↑ Barker 2014, p. 112

- ↑ Fay 2005, p. 28

- 1 2 Fullard, Martin (6 August 2018). "Lord's re-launches Harris Garden". ConferenceNews. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ Booth, Lawrence (2018). The Shorter Wisden 2018. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 139. ISBN 9781472953582.

- ↑ "Harris Garden". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 Warner 1987, p. 292

- 1 2 3 Warner 1987, p. 28

- ↑ Meredith 2012

- ↑ Fay, Stephen (2005). Tom Graveney at Lord's. London: Methuen Publishing. pp. 102–3. ISBN 0413775305.

- ↑ Warner 1987, p. 69

- ↑ Bodleian Library (2011). The Original Rules of Tennis. Melbourne: Victory Books. pp. 29–34. ISBN 978-0522858389. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ↑ Barrett, John (2003). Wimbledon – Serving Through Time. London: Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum. pp. 29, 30. ISBN 978-0-906741-32-0.

- ↑ Somerset, Henry, ed. (1894). Tennis, Lawn Tennis, Rackets, Fives. Badminton Library of Sports and Pastimes (3st ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 133, 134. OCLC 558974625. OL 6939991M.

- ↑ Barrett, John (2001). Wimbledon: The Official History of the Championships. London: CollinsWillow. p. 1. ISBN 0-00-711707-8.

- ↑ Alter, Jamie (14 October 2017). "Harris Garden, hosting tennis at Lord's since 1838 and where rules of lawn tennis were standardised". Firstpost. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 435

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 43

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 40

- ↑ "Cricket on hold as Lord's hosts archery". Wisden India. 26 July 2012. Archived from the original on 31 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ↑ "Lord's hosts Olympic Archery". www.lords.org. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- 1 2 Green 2010, p. 347

- ↑ Vennum, Thomas (2013). American Indian Lacrosse: Little Brother of War. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 269. ISBN 9780801887642.

- ↑ Collins, Joseph Edmund (1884). Canada under the administration of Lord Lorne. Rose Publishing Company. p. 526. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 65

- ↑ Barker 2014, p. 120

- ↑ Felber, Bill (2013). Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century. Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research. pp. 84–5. ISBN 9781933599427. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ↑ Green 2010, p. 195

- ↑ Barker 2014, p. 155

- 1 2 Colwill, Bill (6 November 2006). "World hockey returns to Lord's". Sports Journalists' Association. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ↑ Misra, Jitendra Nath (14 October 2017). "Hockey Asia Cup 2017: India versus Pakistan is an age-old rivalry where emotions take over skills and tactics". Firstpost. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ↑ "Montage: Field hockey match between Indian and Pakistan at the Lord's Cricket Ground in London". Getty Images. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ↑ "Hockey Match Aka Pre-Olympic Hockey Tournament AKA Hockey At Lords 1967". British Pathe. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ↑ "Varsity Match – Past Venues". www.varsityhockeymatch.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ "England Score Historic Triumph". The Straits Times. Reuters. 13 March 1978. p. 22. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- 1 2 Warner 1987, p. 29

- ↑ Warner 1987, p. 31

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood - Highest Team Totals in Test cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood - Lowest Team Totals in Test cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood - Centuries in Test cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood - Five Wickets in an Innings in Test cricket". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood - Most Wickets in a Match in Test cricket". CricketArchive. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Highest Team Totals in ODI cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ "Statistics / Statsguru / One-Day Internationals / Team records". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Centuries in ODI cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Four Wickets in an Innings in ODI cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Highest Team Totals in International Twenty20 matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Lowest Team Totals in International Twenty20 matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "Statistics / Statsguru / Twenty20 Internationals / Batting records". ESPNcricinfo. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Four Wickets in an Innings in International Twenty20 matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Highest Team Totals in first-class cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Lowest Team Totals in first-class cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Double Centuries in first-class cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Seven Wickets in an Innings in first-class cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Most Wickets in a Match in first-class cricket". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Highest Team Totals in List A matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Lowest Team Totals in List A matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – 150 Runs in List A matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Five Wickets in an Innings in List A matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Highest Team Totals in Twenty20 matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Lowest Team Totals in Twenty20 matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Centuries in Twenty20 matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lord's Cricket Ground, St John's Wood – Four Wickets in an Innings in Twenty20 matches". CricketArchive. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

Bibliography

- Altham, Harry (1962). A History of Cricket, Volume 1 (to 1914). George Allen & Unwin.

- Midwinter, Eric (1981). W. G. Grace: His Life and Times. George Allen & Unwin.

- Moorhouse, Geoffrey (1983). Lord's. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 034028210X.

- Rait Kerr, Diana; Peebles, Ian (1987) [First published 1971]. Lord's 1946-1970. London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 1851451153.

- Warner, Pelham (1946). Lord's 1787–1945. Harrap.

Further reading

- Rice, Jonathan (2001). One Hundred Lord's Tests. Methuen Publishing Ltd.

- Wright, Graeme (2005). Wisden at Lord's. John Wisden & Co. Ltd.

.jpg.webp)