The Lords of Westerlo were the feudal lords of the fiefdom (called 'Heerlijkheid' in Dutch or 'Seigneurie' in French) of Westerlo until the abolition of feudalism in 1795. The first known Lord of Westerlo was the Frankish nobleman Ansfried of Utrecht who gave this domain as allodial title to the chapters of Saint-Martin and Saint-Salvator in Utrecht after he became Bishop of Utrecht in 995. Since the late 15th century the Lords of Westerlo have been members of the House of Merode. In 1626 Westerlo was elevated to the rank of marquessate by King Philip IV of Spain in favor of Philippe I de Merode who became the first Marquess of Westerlo. The chief of the House of Merode stil bears the title of Marquess of Westerlo although the feudal rights attached to this title have been abolished since 1795. In the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century the 10th, 11th and 12th Marquess have been elected Burgomaster of Westerlo.

The donation of Ansfried of Utrecht

The exact date of the donation (which included apart from Westerlo proper, the nearby domains of Olen, Westmeerbeek, Buul and others) is not known. The original charter has not been preserved and is only known in medieval copies of the 12th century.[1] It can be supposed that the donation took place at some time between 995 when he became bishop of Utrecht and his death in 1010. The donation was intended to provide the chapters of Sint-Maarten and Sint-Salvator with the necessary financial means to organise the religious service.[2]

The mysterious House of Westerlo and the House of Wezemaal

The chapter of Utrecht gave the manor of Westerlo in fief to local Brabantic noble families. There are indications that in the 11th and 12th centuries a further unknown family by the name of 'van Westerlo' held the fief.[3] The knights of Wezemaal[4] however where gaining power and influence through the important functions they held at the court of the Duke of Brabant. The office of Hereditary Marshall of Brabant brought them great prestige. A certain Hildebrand van Westerlo was mentioned for the last time before 1206 to act as a witness together with Arnold I of Wezemaal. It seems that by 1233–34 his successor Arnold II was in full control of the fief. The oldest preserved lease contract between Arnold II and the chapter of Utrecht dates from 1247. He and his descendants will bear the title Lord of Westerlo.[5] After the death of the father the heir had to present himself before the chapter in Utrecht and renew his oath of fealty.[6]

.svg.png.webp)

The subsequent Lords of Westerlo from the House of Wezemaal are:

Arnold I van Wezemaal (fl. ca. 1170–1200)

- Arnold II van Wezemaal (+before 1264)

x 1 Beatrijs van Breda

x 2 Aleidis van Brabant (daughter of Henry I, Duke of Brabant)- Arnold III van Wezemaal

- Godfried van Wezemaal (+before 1274)

x Isentrudis van Alphen- Arnold IV van Wezemaal (+1302 in the Battle of the Golden Spurs)

x Ida van Bierbeek- Arnold V van Wezemaal (+1317) Dies without heirs.

- Willem I van Wezemaal (+before 1367)

x Jeanne de Beaufort-Fallais- Willem II van Wezemaal (+1372) Dies without heirs.

- Margaretha van Wezemaal

x Richard I de Merode - Jan I van Wezemaal (+1417)

x 1 Ida van Ranst

x 2 Jeanne de Bauffremont (+1429)- Jan II van Wezemaal (+1467) Dies without legitimate heirs.

x Johanna van Bouchout

- Jan II van Wezemaal (+1467) Dies without legitimate heirs.

- Arnold IV van Wezemaal (+1302 in the Battle of the Golden Spurs)

- Arnold II van Wezemaal (+before 1264)

Westerlo disputed between Wezemaal and Merode

Margaretha van Wezemaal (+1393), sister of Jan I van Wezemaal (+1417), Lord of Westerlo, married Richard I de Merode (+1398) in 1361. At this point the House of Merode appears for the first time in the history of Westerlo. Jan I was a canon in Utrecht before marrying Ida van Berchem, widow of the knight Jan van Lier who was believed to have died in combat. After some time the marriage was declared void on the basis of rumors that Ida's first husband Jan van Lier was still alive. After she had been his concubine for some time Jan I finally married Jeanne de Beauffremont. This legitimated the position of their son Jan II who had been born before the union took place. The Brabantic nobility and the Papal authorities in both Rome and Avignon recognized Jan II in 1417 as his fathers legal heir.[7] But the children of Richard I de Merode and Margaretha van Wezemaal proclaimed themselves as the sole legitimate heirs and considered their cousin Jan a bastard. The chapter of Utrecht was inclined to follow this point of view. They hesitated to give him Westerlo and Olen in fief and instead negotiated with his cousin Richard II de Merode. The lease contract with Jan II was not renewed but he refused to leave the fief and did not pay the lease. His cousin Richard II could close a lease contract with the chapter and did pay the lease in place of his cousin, although he had no access to the fief and its revenues. As the land of Westerlo was in the middle of the Duchy of Brabant and far removed from the influence of the chapter of Utrecht, Jan II could hold his position as long as he had the support of the Dukes of Brabant.[8] Meanwhile, the Duchy had become part of the territories ruled by the House of Valois-Burgundy which was keen to expand its power and influence wherever it could. Jan II ignored the allodial rights of the chapter of Utrecht and left Westerlo in his will to the Duke of Brabant, Charles the Bold. However de facto illegal, the Duke accepted the inheritance ignoring in his turn the property rights of the chapter of Utrecht.

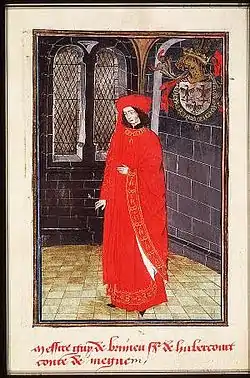

Guy de Brimeu in Westerlo

As if Westerlo was an integral part of his Duchy, Charles the Bold immediately sold (1474) the 'Seigneurie' and the Castle of Westerlo together with others goods and titles of the Lords of Wesemael to Guy de Brimeu, Lord of Humbercourt.[9] De Brimeu was one of Charles the Bold's leading councillors and a knight in the prestigious Order of the Golden Fleece.[10] There is evidence Guy de Brimeu lived in the Castle of Westerlo for a longer period of time between 1475 and his death in 1477. The fief also seems to have been an important source of income for Brimeu.[11] After the sudden death of Charles the Bold, de Brimeu was executed in Ghent on accusation of having negotiated in secret with Louis XI of France over the succession of Charles' daughter Mary of Burgundy.

The House of Merode

The House of Merode immediately started a legal procedure against Antonia de Rambures, widow of Guy de Brimeu. On the 29th of March 1484 the Council of Brabant recognized the fact that the fiefs of Westerlo and Olen were the full property of the chapter of Utrecht.[12] The House of Merode had been paying the lease to the chapter for decades. This made the position of the widow de Brimeu no longer tenable. In 1488 she and her heirs came to an agreement with Jan II de Merode.[13] After decades of struggle he finally became in the possession of the land of Westerlo. Until 1617 Westerlo would remain a fief of the chapter of Utrecht held by the House of Merode.[14] As a result of the Dutch Revolt in that year the Roman Catholic chapter of Utrecht formally seized to exist and Westerlo would become a fief of the Duchy of Brabant.

The subsequent Lords of Westerlo from the house of Merode are:

- Jan (Jean) II de Merode (+1497)

x Marguerite de Melun (+1532) to their son:

- Jan III de Merode (1496–1550)

x Anne van Gistel-Dudzele (+1534) without issue. Jan III designated in his will his nephew Hendrik (Henri) as his heir:

- Hendrik de Merode (1505–1564)

x Françoise van Brederode (+1533) The will was contested by Richard de Merode-Houffalize, of the branch of the Lords of Frentz who was married to Johanna de Merode, Hendrik's elder sister. The Council of Brabant supported Hendrik while the Chapter of Utrecht was in favor of the claims of Richard. It would take 8 years until the dispute was settled in favor of Hendrik de Merode.[15] At his death he was succeeded by his son;

- Jan IV de Merode (+1601)

x Mencia de Glimes-Berghes x Margaretha van Pallant. To their son:

- Philips I de Merode (1568–1627)

x Anna de Merode-Houffalize (+1625)

The Marquess of Westerlo

In 1626 Westerlo is elevated to the rank of marquessate by Philip IV of Spain, Duke of Brabant.[16] Philip I de Merode becomes the first Marquess of Westerlo. At his death the next year the land and the titles are inherited by his son:

- Florent I de Merode (1598–1638) second Marquess of Westerlo

x Anna-Sidonia van Bronckhorst-Batenburg-Stein (+1596). To their son:

- Ferdinand-Philips de Merode (1626–1653) third Marquess of Westerlo

x Madeleine de Gand-Vilain. His successor is his younger brother:

- Maximiliaan de Merode (1627–1675) fourth Marquess of Westerlo

x Isabella-Margaretha de Merode (his niece). To their son:

- Jan-Philips-Eugeen de Merode fifth Marquess of Westerlo, Imperial Fieldmarshall, Knight in the Order of the Golden Fleece

x Maria-Theresia Pignatelli (1682–1718), x Charlotte von Nassau-Hadamar, to their son:

- Jean-Guillaume-Augustin de Merode (1722–1762) sixth Marquess of Westerlo

x Louise-Eléonore de Rohan, to his younger brother:

- Philippe-Maximilien de Merode (1728–1773) seventh Marquess of Westerlo

x Maria-Catherina de Merode-Montfort (1743–1794), Princess of Rubempré and Everberg. To their son:

- Karel-Willem (Charles-Guillaume) de Merode (1762–1830) eighth Marquess of Westerlo, appointed mayor of Brussels by Napoleon (1805–1809)x Maria-Josepha d'Oignies-Mastaing (1760–1842), Princess of Grimbergen.

The end of the marquessate of Westerlo

Karel-Willem (Charles-Guillaume) would be the last feudal Marquess of Westerlo.[17] With the annexation of the Austrian Netherlands to the First French Republic on the first of October 1795 feodality was definitively abolished. The marquessate of Westerlo seized to exist and was divided in municipalities.[18] The Merode Family lived in exile in Maastricht and later in Prussia and Saxony. The country estate and extensive domains in the region were confiscated by the Republic and put on sale. They could be bought back by agents acting on behalf of the exiled family. Karel-Willem and his family returned to Belgium in 1800. The title of 'Marquess of Westerlo' was recognized by King William I of the Netherlands in 1823 and will be inherited by his eldest son:

- Count Henri de Merode-Westerloo (1762–1846) ninth Marquess of Westerlo

x Louise de Thesan d'Espendaillan (1787–1862). To their son:

- Count Charles-Antoine-Ghislain de Merode-Westerloo (1824–1892) tenth Marquess of Westerlo, and elected burgomaster of Westerlo (1879–1892).

x Marie-Nicolette, princesse d'Arenberg (1830–1905). To their son:

- Count Henri de Merode-Westerloo (1856–1908) eleventh Marquess of Westerlo, and elected burgomaster of Westerlo (1892–1908).

x Nathalie, princesse de Croÿ-Dülmen (1863–1957). To their son:

- Prince Charles de Merode-Westerloo (1887–1977) twelfth Marquess of Westerlo, and elected burgomaster of Westerlo (1913–1946).[19]

x Marguerite–Marie de Laguiche (1895–1988). The couple had no children but adopted:

- Prince Albert de Merode (1915–1958) from the cadet branch of Félix de Merode (which on extinction of the branch of Henri de Merode would become the senior branch). His heirs inherited the estates in and around Westerlo, and the Castle of Merode in Langerwehe (Germany) and the 'Hôtel de Merode' in Brussels. The titles of Marquess of Westerlo, Prince of Grimbergen and Prince of Rubempré, as well as the status of head of the family passed to the senior male member of the branch of Félix de Mérode:[20]

- Prince Xavier de Merode (1910–1980) thirteenth Marquess of Westerlo, and elected burgomaster of Lanaken.

x Elisabeth Alvar de Biaudos de Castéja. To their son:

- Prince Charles-Guillaume de Merode (1940) is the fourteenth and present Marquess of Westerlo.

x Princesse Hedwige de Ligne de la Tremoille. His heir apparent as Marquess of Westerlo is his eldest son Prince Frédéric de Merode (1969).

Notes

- ↑ Brussels, Algemeen Rijksarchief, FAMW, LA 1335, Copy of the donation charter from the register of the Chapter Church of Oudmunster in Utrecht, Translation in Middle Dutch from the 12th century ; Utrecht, Bischoppelijk Archief, Cartularium from the Liber Donationum, no. 43, fol. 25, 12th century copy of the original Latin text

- ↑ Eduard van Ermen, De Utrechtse kapittels Sint-Maarten en Sint-Salvator (Oudmunster) en hun bezittingen in de Antwerpse Kempen, Leuven, 1983, pp.28–51

- ↑ Kris De Winter, Westerlo, land van Merode, Westerlo, 2000, p.12

- ↑ The archaic spelling 'Wesemael' or 'Wesemaele' is mostly seen in older texts and is still commonly used in French texts.

- ↑ Eduard van Ermen, De landelijke bezittingen van de heren van Wezemaal in de Middeleeuwen, 2 vols., Leuven, 1982–1986

- ↑ De Winter 2000, p. 15

- ↑ De Winter 2000, pp.27–28

- ↑ Van Ermen 1982–1986, vol.II, pp. 44–53,

- ↑ Van Ermen 1982–1986, vol.II, p.111

- ↑ Werner Paravicini, Guy de Brimeu, Der Burgundische Staat und seine adlige Führungsschicht unter Karl dem Kühnen, Bonn, 1975, passim

- ↑ Paravicini 1975, p.364, 412 and pp.418–421

- ↑ De Winter 2000, p.30

- ↑ Brussels, Algemeen Rijksarchief, Charter of April 14th 1488; Agreement between Jan II de Merode and the widow and children of Guy de Brimeu concerning the land of Westerlo, Brussels, Council of Brabant, April 15th 1488

- ↑ Vannoppen 1989, p.41

- ↑ De Winter 2000 p.55 & note 1 with references to the archival documents

- ↑ Le Roy, Jacques (1706). L'érection de toutes les terres, seigneiries et familles titrées du Brabant, prouvée par des extraits des lettres patentes tirez des originaux ... Amsterdam: s.n. p. 21. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ E. Duchesne, 'Charles-Guillaume-Ghislain comte de Mérode', Biographie Nationale, vol.XIV, col.534–539

- ↑ Henri Vannoppen, Het kasteel van Westerlo en de Prinsen de Merode,Westerlo, 1989, p.71-74

- ↑ Op de Beeck 1974, pp.132–142

- ↑ Vannoppen 1989, pp.127–134

References

- De Winter, Kris, Westerlo, land van Merode, Westerlo, 2000 ISBN 90-73062-02-0

- Op de Beeck, Evrard, Meer eer dan eerbetoon, Een greep uit de rijke geschiedenis van de Familie de Merode, Westerlo, 1975

- Paravicini, Werner, Guy de Brimeu, Der Burgundische Staat und seine adlige Führungsschicht unter Karl dem Kühnen, Bonn, 1975

- Van Ermen, Eduard, De landelijke bezittingen van de heren van Wezemaal in de Middeleeuwen, 2 vols., Leuven, 1982–1986

- Van Ermen, Eduard, De Utrechtse kapittels Sint-Maarten en Sint-Salvator (Oudmunster)en hun bezittingen in de Antwerpse Kempen, Leuven, 1983

- Vannoppen, Henri, Het kasteel van Westerlo en de Prinsen de Merode, Westerlo, 1989