The furniture of the Louis XV period (1715–1774) is characterized by curved forms, lightness, comfort and asymmetry; it replaced the more formal, boxlike and massive furniture of the Louis XIV style. It employed marquetry, using inlays of exotic woods of different colors, as well as ivory and mother of pearl.

The style had three distinct periods. During the early years (1715–1730), called the Regency, when the King was too young to rule, furniture followed the massive, geometric Style Louis XIV style. From 1730 until about 1750, the period known as the first style, it was much more asymmetrical, ornate and exuberant, in the fashion called rocaille. From about 1750 to the King's death in 1774, a reaction set in against the excesses of the rocaille. The Louis XV style showed the influences of Neo-classicism, based on recent archaeological discoveries in Italy and Greece. It featured Roman and Greek motifs. The later furniture featured decorative elements of Chinoiserie and other exotic styles.[1]

Louis XV furniture was designed not for the vast palace state rooms of the Versailles of Louis XIV, but for the smaller, more intimate salons created by Louis XV and by his mistresses, Madame de Pompadour and Madame DuBarry. It included several new types of furniture, including the commode and the chiffonier, and many pieces, particularly chairs and tables, were designed to be moved easily rearranged or moved from room to room, depending upon the kind of function.[2]

History

With the death of Louis XIV on 1 September 1715, his grandson, Louis XV, born in 1710, became King. Because of his young age, France was ruled by a Regent, Philippe of Orleans, until 1723. During this period, the style of furniture changed little from the Louis XIV period; it was massive, lavishly decorated and solemn, designed for the gigantic state halls of the new Palace of Versailles. In 1722 Louis XV moved from Paris, where he had lived with the Regent, to Versailles, began his own rule, and gradually imposed his own taste on the arts, architecture, and furniture.[3]

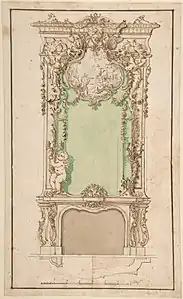

Louis left the exterior of Versailles and the other palaces largely unchanged, but beginning in 1738 he extensively redesigned the interiors, creating the petits apartments, or smaller apartments and salons for himself, the Queen, Marie Leszczyńska, whom he married in 1725, and later, for his primary mistresses, Madame Pompadour and Madame du Barry. In these salons the traditional etiquette and formality of Louis XIV was abandoned. These new suites of smaller rooms were furnished in a new style that met the needs of comfort, intimacy and elegance. Beginning in about 1730, His preference was for the style called rocaille, a term which referred to an ornamental decoration resembling a stylized seashell, a style which expressed gaiety and fantasy. The ornament appeared rarely on the exteriors of the new buildings, but lavishly in the interiors, on the walls, ceilings, and furniture.[3] The architects Robert de Cotte and Ange-Jacques Gabriel remade the interiors of the Palace of Versailles, the Palace of Fontainebleau, and the Château de Compiègne in the new style.[4]

Palatial residences with rocaille interiors soon appeared In Paris. They included the Hôtel Soubise in Paris, (now the National Archives) in 1705; the Hôtel Matignon (now the residence of the French Prime Minister) in 1721, by Jean Courtonne; and the Hôtel Biron (now the Musée Rodin) by Jean Aubert. They also appeared in the French provinces, the royal residence by Emmanuel Héré in Nancy, and also in Aix-en-Provence and Bordeaux. All of these buildings featured rooms arranged in the new style; the bedrooms took on new importance, and were surrounded by smaller anterooms and cabinets, including an entirely new kind of room, the dining-room. All of them needed new furniture to match the new style and arrangement.[5]

For a quarter of a century, the furniture designs of the rocaille style was dominant, particularly under the influence of Juste-Aurèle Meissonier (1695-1750), the Italian-born architect who became royal architect and designer of Louis XV, and the ornament designer Nicolas Pineau (1684-1754). Under their influence, straight lines disappeared, replaced by curves, ornaments lost all symmetry, and garlands of flowers appeared everywhere. Designs inspired by Chinese art and other exotic sources appeared in profusion, though the rocaille style never reached the excess of exuberance of the Rococo style that appeared in Italy, Austria and Germany.[6]

In the 1740s, the style began to slowly change; decoration became less extravagant and more discreet. In 1754 the brother of Madame de Pompadour, the Marquis de Marigny, accompanied the designer Nicolas Cochin and a delegation of artists and scholars to Italy to see the recent discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum, and made a grand tour of other classical monuments. They returned full of enthusiasm for a new classical style, based on the Roman and Greek monuments. In 1754 they published a manifesto against the Rocaille style, calling for a return to classicism. Marigny, after the death of Louis XV, later became director of buildings for Louis XVI.[6]

Between 1755 and 1760, the forms of furniture and interior decoration began to change into what became known as the Second Style Louis XV, or the Style Transition. The rocaille decoration remained, but became more discreet and restrained. Secondly, the new wave of enthusiasm for ancient Greece and Rome brought a series of new decorative themes, though the lines of the furniture were not much changed. This marked the beginning of what became French neoclassicism or Louis XVI style.[7]

Designers

The earliest furniture designers under Louis XV during the Regency included Claude III Audran, who had been responsible for furniture design under Louis XIV; Pierre Lepautre, who in 1699 became chief designer for Louis XIV, and Gilles-Marie Oppenordt, born in Holland, who became the furniture designer for the Regent. Opponordt's designs in 1714 for the decor of the Hotel de Pomponne on Place des Victoires, featuring curving S and C forms, helped introduce the new style to Parisians. Another important figure in introducing the new style was the painter Watteau, a former pupil of Audran, who, besides his famous paintings, made arabesque designs for the woodwork of the new chateau of La Muette. [8]

In the 1730s, notable designers included the sculptor and architect Nicolas Pineau and the jeweler Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier; their work featured a greater amount of asymmetry, floral design twisting elements and counter-curves. In 1736 the carver and jewelry sculptor Jean Mondon published Premier Livre de form rocquaille et carte, the first book specifically on the style, and was among the first to include elements of Chinoiserie, notably dragons, a phoenix, and other figures. Engravings of their designs for furniture, woodwork and other decoration circulated widely throughout Europe, making the rocaille style a model for artists and craftsmen in other counties to follow.[8]

Arabesque design by Claude III Audran (about 1700)

Arabesque design by Claude III Audran (about 1700) Design for a writing desk by Gilles-Marie Oppenordt (1675-1700)

Design for a writing desk by Gilles-Marie Oppenordt (1675-1700) Design for a mantlepiece by Nicolas Pineau (early 18th C.)

Design for a mantlepiece by Nicolas Pineau (early 18th C.)%252C_pl._47_in_Oeuvre_de_Juste-Aurele_Meissonnier_-_Google_Art_Project_(down_table_cropped).jpg.webp) Side table design by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (about 1739)

Side table design by Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (about 1739) Rocaille design with Chinese Figure by Jean Mondon (1736)

Rocaille design with Chinese Figure by Jean Mondon (1736)

Craftsmen

Louis XV furniture was created by the collaboration of complex network of designers and craftsmen. The Menuisier, made the wooden framework of the furniture, which was held together by its structure and wooden chevilles or dowels; the use of nails or glue was forbidden. The Ebenist then covered the frame and native woods with thin pieces of exotic woods, called marquetry. In the reign of Louis XIV ebony was most often used for this covering, but, beginning in 1675-80, more exotic and colorful woods were used, which could give more picturesque effects. This were sometimes placed in cubic designs, or checkerboards, or representing arabesques, floral patterns, trophies, or picturesque scenes. Originally the plaques were about a centimeter thick, but by the end of the period plaques were only slightly more than two millimeters thick.[9] Then the furniture was completed by the bronziers, who made the handles and knobs; the doreurs who gilded them; the fondeurs, who made metalwork; the chiselers or wood sculptors, who made the decorate details, legs, and other carvings; the laqueursand vernisseurs, who applied multiple coats of lacquer or varnish.[10]

After 1751 each work was signed by the master craftsman who oversaw the work. This mark, called the Estampille, used a heated iron to mark the piece with the initials of the master. It was usually placed on the back of the rear traverse of chairs, under the marble of commodes and secretaries, and under the surrounding ceinture of tables. marks are often missing, either forgotten by the craftsman, or defaced. Given the high value of signed pieces by famous craftsmen, Counterfeit Estampilles are not unknown.[9]

Chairs and sofas

Between 1769 and 1775, the furniture designer André Jacob Roubo published a series of books of engravings called L'Art du menusier, detailing the categories and styles. He divided the chairs into two categories; those with a straight back, called á la Reine, and those with a rounded back, called en cabriolet.[6] The chairs en cabriolet were usually lighter, often had cane seats and backs, and could be moved around easily. He included some new styles, notably the voyeuse a small chair with an armrest on the back, so the person seated could either face forward or turn around and sit astride the chair with his arms on the back of the chair.[11]

The fauteuils, or armchairs, were larger and designed for comfort; their styles evolved during the reign of Louis XV. During the early years of the Regency (1715-23) the armchairs had short curved feet, the top of the back was slightly curved, while the supports of the back and the arms were straight. The armchairs of the middle Louis XV period (1723-1750) were smaller than those of the Louis XIV period, but more comfortable. The legs were more curved, the top of the back was rounded, and often had a small ornamental design. The back of the chair took on a more graceful violin form. This form became known as the Chaise à la Reine, or "Chair of the Queen."[11]

A variety of other new forms appeared, designed especially for comfort. The Bergere had a low seat with an additional cushion, and sometimes added padded wings atop the arms on either side of the back which protected the head against drafts, which also made it easier to take naps. Other new types that were introduced were the marquise, basically an armchair expanded to seat two persons, and the chaise longue, an armchair with a lengthened seat to support the legs, and the Duchesse, where two chairs could be combined with an extension between.[12] Another new type was the Fauteuil de cabinet, a type of chair designed to go with a desk, and to provide more comfort while writing. It was usually upholstered in leather fastened with gilded nails to the frame, had rounded angles, and one leg of the chair was placed in the front, another directly behind, for greater stability. The curved back and arms of the chair enveloped the person seated.[13]

The passion for the oriental and exotic soon influenced the furniture. A new kind of seat, La Sultane was introduced, with two places; another type called the Ottomane, with the back in a form called en gondola, and arms which wrapped around the oval seat, and another variety, called la papose, without arms or a back; and finally Le Sofa, which featured cushions which could be moved and rearranged.[12]

The last phase of the Louis XV style, the gradual transition toward the neoclassical, had a limited effect on chairs. The basic forms remained, but the decoration increasingly took the form of garlands of flowers called a l'ántique in a repetitive rhythm, which opposed the sinuous form of the carved legs and frame.[7]

Armchair by Nicolas-Quinibert Foliot (1749)

Armchair by Nicolas-Quinibert Foliot (1749) Armchair with padded wings (about 1750)

Armchair with padded wings (about 1750).jpg.webp) Louis XV salon with Duchesse divided seat (1760-65) (Louvre)

Louis XV salon with Duchesse divided seat (1760-65) (Louvre)_MET_SF21_34.jpg.webp) Fauteiul de Bureau or desk chair (c. 1750)

Fauteiul de Bureau or desk chair (c. 1750) Louis XV armchair with Beauvais tapestry

Louis XV armchair with Beauvais tapestry_MET_DP221524.jpg.webp) Canapé by Jean Baptiste Oudry (1754-56) Metropolitan Museum

Canapé by Jean Baptiste Oudry (1754-56) Metropolitan Museum_MET_DT8906.jpg.webp) An Ottomane sofa (1750-60) by Jean Baptiste Tilliard, in an oval shape, an example of the Turquoise or Turkish style

An Ottomane sofa (1750-60) by Jean Baptiste Tilliard, in an oval shape, an example of the Turquoise or Turkish style A chaise-longue, with separate chair and extension. (Hôtel de Caumont, Aix-en-Provence)

A chaise-longue, with separate chair and extension. (Hôtel de Caumont, Aix-en-Provence)

Consoles and tables

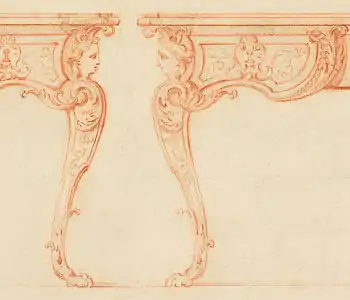

The Table en console or Console table, was designed to be placed against a wall, often in front of mirror, and held statuettes or porcelain objects. It was among the most lavishly decorated pieces of furniture of the early Louis XV period. It was usually made of oak, carved and gilded, and drenched with rocaille decoration, usually in the form of seashells and foliage. The and legs in the form of an exaggerated S or a reverse S. The supporting frame under the table was also highly decorated, sometimes holding porcelain objects, and sculpted figures of dragons or other mythical animals. The face of the table often had rocaille masks. a g rocaille modeled after seashells and foliage. They usually had a plaque of colored marble on top.[14]

Another popular style of table was the bureau plat, or flat desk. It was introduced by André-Charles Boulle around 1710 in the late reign of Louis XIV, as a replacement for the desk mounted atop two columns of drawers. The early versions by Boulle were made of ebony and dark wood, and had eight legs, and six drawers, which were decorated with gilded bronze handles. The slightly curved legs ending in gilded ornaments in the shape of deer's feet. Gilded bronze espagnolettes decorated the corners and legs. Later in the period, the flat desks featured an abundance of marquetry; they were made of oak or spain, were embedded with thin plaques of exotic woods of contrasting colors. Another celebrated creator of tables was Charles Cressent, who carried on the refined and harmonious ornamental style of Boulle.[15]

A number of small, specialized and portable tables appeared around of after 1755, some of them designed for Madame de Pompadour. These included the table de chevet, a very small utility table made of oak and inlaid with rosewood and other precious woods, which could be put in the closet when not needed; the Table d'en-cas, or "Just in case" table, a small piece with two drawers, small cupboard with a grilled door, and a marble top; the Chiffonière, a small table with gracefully curving legs and a porcelain top. Another small table was the cabaret or á café table, with a small marble top and long legs, on which coffee or drinks could be served. The version introduced in 1770 featured geometric designs and a neoclassical frieze around the plateau.[16]

Another popular type of small table was the Table de toilette, or dressing table. One particular variety, en coeur, or heart-shaped, was especially designed for men; it stood on three legs mounted on rollers, contained an assortment of drawers and small compartments, and featured a folding mirror on top.[17]

In the late, second style of Louis XV, after 1750, the tables lost the rococo curves and took on classical (or imagined classical) details, including table legs in the form of Doric columns; griffon paws and lion paws on the feet;, trophies of arms, friezes, and figures of nymphs, tripods and horns of plenty. This style was termed, rather imaginatively, à la Greque, and presaged the neoclassical period to come.[18]

Console table, Hôtel de Bourvallais (now Ministry of Justice)

Console table, Hôtel de Bourvallais (now Ministry of Justice) Writing table by Charles Cressent (1730-35)

Writing table by Charles Cressent (1730-35) Coiffeuse table with marquetry by Pierre Roussel (about 1770)

Coiffeuse table with marquetry by Pierre Roussel (about 1770) Men's dressing table en coeur by Charles Topino (about 1773)

Men's dressing table en coeur by Charles Topino (about 1773)

Commodes and chests

The Commode (whose name means "convenient") was invented under Louis XIV to replace the coffre, or large chest. It was heavy and boxlike, with short legs, and abundant decoration of gilded bronze. During the Regency and early style of Louis XV, particularly in the commodes of Charles Cressent, commodes became more graceful, with longer S-shaped legs and espagnolettes, or stylized female torsos, on the corners above the legs. The fronts of commodes became more rounded in form. Gilded bronze vines curled and wound across the facade. Bronze ornaments in the form of masks were replaced by faces of smiling women, palmettes, and, later in the period, a new theme, s stylized bat wing. The seashell was a common central element of the rocaille decoration, often combined with acanthus leaves. Handles of drawers were shaped like intertwined flowers. Sculpted images of various animals also appeared near the end of the early period.[19]

A large number of skilled ébénistes from around Europe were employed to make fine wood Commodes and other furniture for the new apartments built by Louis XV at Versailles, Fontainebleau, and his other residences. They included Jean-François Oeben, Roger Vandercruse Lacroix, Gilles Joubert, Antoine Gaudreau, and Martin Carlin.[20]

As the period advanced, the marquetry, or inlays of different-colored woods, became finer and more dominant. Various geometric patterns, including the checkerboard, stars, and losanges, appeared, along with bouquets of flowers made of fine marquetry.[20] New techniques of lacquering wood were introduced, based on Chinese and Japanese techniques, which were frequently used on the front panels of commodes. A particular variation, called the façon de Chine or "Chinese fashion" was introduced, which contrasted the gilded bronze ornament and handles against the black lacquered wood. The designs often borrowed motifs from Chinese and Japanese art.[19]

Beginning in 1755-60, the reaction against the excesses of the rocaille form began. The shapes of commodes became more boxlike, the front flat, and the legs shorter, though they retained their slight S curve. The faces of the commodes were decorated with geometric friezes of oak leaves, roses or serpents and drapery motifs, the early manifestation of the Greco-Roman Neoclassical style.[7]

A new form of commode, the Cartonnier, appeared in the 1760s, inspired by somewhat fantastic ideas of ancient Greek furniture. Its front was lavishly decorated with friezes, trophies of arms and lions heads, while on the top, a pedestal supported by two scrolled volutes held a group of replicas of classical Greek statues.[21]

Commode by Charles Cressent, Waddesdon Manor, (1730)

Commode by Charles Cressent, Waddesdon Manor, (1730) Commode by Antoine Gaudreau in the apartment of the Dauphin at Versailles (1745)

Commode by Antoine Gaudreau in the apartment of the Dauphin at Versailles (1745) Commode by Bernard II van Risamburgh, Getty Museum, (circa 1750)

Commode by Bernard II van Risamburgh, Getty Museum, (circa 1750) Lacquered Commode in Chinoiserie style, by Bernard II van Risamburgh, Victoria and Albert Museum (1750-1760)

Lacquered Commode in Chinoiserie style, by Bernard II van Risamburgh, Victoria and Albert Museum (1750-1760)

Desks

During the reign of Louis XV, the bureau and secretaire gradually evolved into the form of the modern desk, along with a wide variety of more elaborate variations. At the beginning the 18th century, André Charles Boulle and Charles Cressent had created the bureau au plat. a writing table with columns of drawers, graceful curving legs, gilded bronze decoration, and fine marquetry in geometric forms. Jacques Dubois made a series of celebrated desks in this fashion the 1740s.

Around 1750, a new variety appeared, called the Secretaire à capuchin or à la Bourgone, which contained a section of drawers which could be raised up, while the top folded out into a writing surface. In addition to the drawers, it contained a number of secret compartments concealed within. Numerous other variants appeared soon afterwards; the Secrétaire en pent, or sloping desk first appeared in about 1735. It was a small cabinet with a sloping front which opened out into a writing surface. It was also called en dos d'âne, or "style of donkey's back". Madame de Pompadour possessed one of these, made between 1748–52, with a varnish of red and a blue in the Chinese style, which combined rocaille and exoticism. Mathieu Criaerd made a secretary in this style in about 1750, with marquetry of violette, amarante, satin wood and gilded bronze.[22]

A much simpler variety, the pupitre à écrire debut, of pulpit for writing while standing, arrived at about the same time. The finest models were usually made of oak and fir, covered with marquetry of rose wood, satin wood, and amaranth. They had small wheels to be moved around easily, had a locked compartment under the sloping top surface, and shelves below for large documents.[22]

The Secretaire en armoire was a larger and more vertical variation, based on the form of an armoire; it was a large chest with a writing surface that folded down and drawers and shelves inside. It was designed to stand against a wall, and appeared in about 1750. It often featured a marquetry in a geometric pattern resembling cubes of dark and light wood, a design very popular in the last years of the Louis XV period.

The Bonheur-du-jour was a small desk with cabinet which appeared in about 1760. Following the new style of the late Louis XV period, it had no gilded bronze. It featured graceful curbed legs, but the top part was geometric, with delicate inlays of marquetry flowers.

The most celebrated new type of desk invented under Louis XV was the Bureau à cylindre or rolltop desk, which appeared in about 1760. The master of this form was Jean-François Oeben. It had no gilded bronze other than a delicate frieze around the top; very fine marquetry of flowers, and an interior with secret compartments. Many variants were made, including the desk of Louis XV now on display at Versailles.[22]

Bureau Plat by Bernard II van Risamburgh (1745)

Bureau Plat by Bernard II van Risamburgh (1745)_MET_SF2007_90_7_img1.jpg.webp) Secretaire en pent by Bernard II van Risamburgh (1745)

Secretaire en pent by Bernard II van Risamburgh (1745)

Bonheur-du-Jour by Martin Carlin, (1766), Nissim de Camondo Museum, Paris

Bonheur-du-Jour by Martin Carlin, (1766), Nissim de Camondo Museum, Paris_MET_DP105306.jpg.webp) Early neoclassical drop-front desk by Martin Carlin (1773)

Early neoclassical drop-front desk by Martin Carlin (1773)

Beds

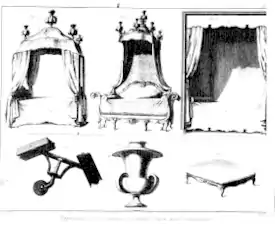

Under Louis XV the bedroom was a place of ceremony; the formal awakening of the King in his bed chamber (even if he had actually slept elsewhere) was a formal event, attended by members of the Court and visitors to the Palace. The form of the bed and its covering evolved under Louis XV. Early beds had four posts and a canopy suspended from a rectangular form on top. Under Louis XV, the Lit à la polonaise (Polish bed) appeared, with a canopy suspended from a crownlike structure; and the Lit à la Duchesse, where the canopy was supported only from one end. The bed was usually separated from the rest of the room by a balustrade, and stools were arranged outside the balustrade for the Court to witness the formal awakening.

The famous Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert (1751–72) included images of beds à la Polonaise, and à la Turque (a more ornate and exotic version of the Duchesse) and a bed placed into an alcove. (Volume 8, pg. 216).

1755 Lit à la polonaise by Nicolas Heurtaut,[25] with folding stools arranged before it, Bedchamber of the Dauphine at the Palace of Versailles. Note square frame under crown is covered with the same fabric.

1755 Lit à la polonaise by Nicolas Heurtaut,[25] with folding stools arranged before it, Bedchamber of the Dauphine at the Palace of Versailles. Note square frame under crown is covered with the same fabric..JPG.webp) Bedchamber with bed à la Duchesse. Hôtel de Soubise

Bedchamber with bed à la Duchesse. Hôtel de Soubise Engravings of beds from the Encyclopédie (1751–72)

Engravings of beds from the Encyclopédie (1751–72)

Transition From Rocaille to neo-classicism

Later in the reign of Louis XV, between 1755 and 1760, tastes in furniture began to change. The rocaille designs began more discreet and restrained, and the influence of antiquity and neo-classicism began to appear in new designs of furniture. The Commodes became to have more geometric forms; the decoration turned from rocaille to geometric forms, garlands of oak leaves, flowers and classical motifs. The legs gradually changed from s-curves to straight, often modeled after Greek or Roman columns, tapering to a point. Common decorations included stylized pine cones, and knotted ribbons. A new type of tall cabinet, the Cartonnier, made its appearance between 1760 and 1765. It took its inspiration from Greek mythology and architecture, with friezes, vaulting, sculpted trophies, bronze lion heads, and other classic, elements.[26]

The ebenistes Jean-Henri Riesener, Jean-François Leleu, Martin Carlin and David Roentgen and menuisier Georges Jacob were among the most important creators of the late Louis XV transition style. Their careers continued and reached their peak during the following reign of Louis XVI.

Early desk by David Roentgen (1769)

Early desk by David Roentgen (1769) Jewel box of the Dauphine Marie Antoinette by Martin Carlin (1770)

Jewel box of the Dauphine Marie Antoinette by Martin Carlin (1770) Sofa with Aubusson tapestry upholstery (1750–75)

Sofa with Aubusson tapestry upholstery (1750–75).jpg.webp) Table chiffonère, Louvre (1774)

Table chiffonère, Louvre (1774) Chair by Georges Jacob (1770)

Chair by Georges Jacob (1770) Commode by Martin Carlin with Japanese lacquer veneer (1773)

Commode by Martin Carlin with Japanese lacquer veneer (1773)

List of master furniture designers and creators under Louis XV

- Claude Audran III (1658-1734)

- André Charles Boulle (1642-1732)

- Jean-Philippe Boulle (1678-1744)

- Charles Cressent (1685-1768)

- Mathieu Criaerd (1689 — 1776)

- Louis Delanois (1731-1792)

- Antoine Gaudreau (1680-1746)

- Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier (1695-1750)

- Jean-François Oeben (1721–63)

- Gilles-Marie Oppenordt (1672-1742)

- Nicolas Pineau (1684-1754)

- André Jacob Roubo (1739–91)

- Bernard II van Risamburgh (1730–67)

- David Roentgen (1743-1807)

Notes and Citations

- ↑ Ducher 1988, pp. 136–37.

- ↑ Renault & Lazé 2000, pp. 63–73.

- 1 2 Renault & Lazé 2000, pp. 63–67.

- ↑ Wiegandt 2005, pp. 9–13.

- ↑ Wiegandt 2005, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Wiegandt 2005, p. 54.

- 1 2 3 Ducher 1988, p. 146.

- 1 2 De Morant 1970, p. 355.

- 1 2 Wiegandt 2005, p. 22-25.

- ↑ De Morant 1970, p. 379.

- 1 2 De Morant 1970, p. 380.

- 1 2 De Morant 1970, p. 381.

- ↑ Wiegandt 2005, p. 64.

- ↑ Wiegandt 2005, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Wiegandt 2005, pp. 42–50.

- ↑ Wiegandt 2005, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Wiegandt 2005, pp. 92.

- ↑ Ducher 1988, p. 138.

- 1 2 Renault & Lazé 2000, pp. 63–65.

- 1 2 Ducher 1988, p. 144.

- ↑ Ducher 1988, pp. 146–147.

- 1 2 3 Wiegandt 2005, pp. 85–88.

- ↑ "Nicolas Heurtaut's Masterpieces: The Million Euro Sofas Fit for a King's Mistress". 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "(#270) Exceptionnelle paire de canapés en coin de feu à châssis et à accotoir unique en noyer et hêtre sculptés et redorés à l'huile d'époque Louis XV, vers 1755, estampillée N. HEURTAUT".

- ↑ History and date of set,[23] part of same set, including image[24]

- ↑ Ducher 1988, pp. 146–47.

Bibliography

- De Morant, Henry (1970). Histoire des arts décoratifs. Librarie Hacahette.

- Cabanne, Perre (1988), L'Art Classique et le Baroque, Paris: Larousse, ISBN 978-2-03-583324-2

- Ducher, Robert (1988), Caractéristique des Styles, Paris: Flammarion, ISBN 2-08-011539-1

- Renault, Christophe (2006), Les Styles de l'architecture et du mobilier, Paris: Gisserot, ISBN 978-2-877-4746-58

- Renault, Christophe; Lazé, Christophe (2000), Les styles de l'architecture et du mobilier, Editions Jean-paul Gisserot, ISBN 978-2877474658

- Wiegandt, Claude-Paul (2005), Le Mobilier Français- Régence Louis XV, Paris: Massin, ISBN 2-7072-0254-1

- Louis XV style. (2008). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online