| "America's Home for Racing" | |

|---|---|

| |

Quad Oval (1960–present)  Roval (2018–present)[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Location | 5555 Concord Parkway South Concord, NC, 28027 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (UTC−4 DST) |

| Coordinates | 35°21′09″N 80°40′57″W / 35.35250°N 80.68250°W |

| Capacity | Depending on Configuration 94,000-171,000[1][2][3] |

| Owner | Speedway Motorsports (1975–present) |

| Operator | Speedway Motorsports (1975–present) |

| Broke ground | 1959 |

| Opened | 19 June 1960 |

| Construction cost | $1.25 million |

| Architect | Bruton Smith and Curtis Turner |

| Former names | Charlotte Motor Speedway (1960–1998, 2010–present) Lowe's Motor Speedway (1999–2009) |

| Major events | Current: NASCAR Cup Series Coca-Cola 600 (1960–present) Bank of America Roval 400 (1960–present) NASCAR All-Star Race (1985, 1987–2019) NASCAR Xfinity Series Alsco Uniforms 300 (1978–present) Drive for the Cure 250 (1973–present) NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series North Carolina Education Lottery 200 (2003–present) ARCA Menards Series General Tire 150 (1996–2004, 2018–2019, 2021–present) Former: IMSA SportsCar Championship Grand Prix of Charlotte (1971, 1974, 1982–1986, 2000, 2020) Trans-Am Series (1981, 2000, 2022) IndyCar VisionAire 500K (1997–1999) Pirelli World Challenge (2000, 2007) AMA Superbike Championship (1977, 1980, 1991–1993) Can-Am (1978–1979) |

| Quad Oval (1960–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 1.500 miles (2.414 km) |

| Turns | 4 |

| Banking | Turns: 24° Straights: 6° |

| Race lap record | 0:24.735 ( |

| NASCAR Road Course "Roval" (2019–present)[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.280 miles (3.669 km) |

| Turns | 17 |

| Banking | Oval turns: 24° Oval straights: 5° |

| Race lap record | 1:18.188 ( |

| NASCAR Road Course "Roval" (2018)[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.280 miles (3.669 km) |

| Turns | 17 |

| Banking | Oval turns: 24° Oval straights: 5° |

| Race lap record | 1:18.078 ( |

| Roval (1971–2014) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 2.250 miles (3.621 km) |

| Turns | 18 |

| Banking | Oval turns: 24° Oval straights: 5° |

| Race lap record | 1:05.524 ( |

Charlotte Motor Speedway is a motorsport complex located in Concord, North Carolina, 13-mile (21 km) outside Charlotte. The complex features a 1.500 mi (2.414 km) quad oval track that hosts NASCAR racing including the prestigious Coca-Cola 600 on Memorial Day weekend, and the Bank of America Roval 400. The speedway was built in 1959 by Bruton Smith and is considered the home track for NASCAR with many race teams located in the area. The track is owned and operated by Speedway Motorsports with Greg Walter as track president.

The 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) complex also features a state-of-the-art 0.250 mi (0.402 km) drag racing strip, ZMAX Dragway. It is the only all-concrete, four-lane drag strip in the United States and hosts NHRA events. Alongside the drag strip is a state-of-the-art clay oval that hosts dirt racing including the World of Outlaws finals among other popular racing events.

History

Charlotte Motor Speedway was designed and built by Bruton Smith and partner and driver Curtis Turner in 1959. The first World 600 NASCAR race was held at the 1.500 mi (2.414 km) speedway on June 19, 1960. On December 8, 1961, the speedway filed bankruptcy notice. Judge J. B. Craven of United States District Court for the Western District of North Carolina reorganized it under Chapter 10 of the Bankruptcy Act; Judge Craven appointed Robert "Red" Robinson as the track's trustee until March 1962. At that point, a committee of major stockholders in the speedway was assembled, headed by A. C. Goines and furniture store owner Richard Howard. Goines, Howard and Robinson worked to secure loans and other monies to keep the speedway afloat.[4]

By April 1963 some $750,000 was paid to twenty secured creditors and the track emerged from bankruptcy; Judge Craven appointed Goines as speedway president and Howard as assistant general manager of the speedway, handling its day-to-day operations. By 1964 Howard become the track's general manager, and on June 1, 1967, the speedway's mortgage was paid in full; a public burning of the mortgage was held at the speedway two weeks later.[5]

Smith departed from the speedway in 1962 to pursue other business interests, primarily in banking and auto dealerships from his new home of Rockford, Illinois. He became quite successful and began buying out shares of stock in the speedway. By 1974 Smith was more heavily involved in the speedway, to where Richard Howard by 1975 stated, "I haven't been running the speedway. It's being run from Illinois."[6] In 1975 Smith had become the majority stockholder, regaining control of its day-to-day operations. Smith hired H. A. "Humpy" Wheeler as general manager in October 1975, and on January 29, 1976, Richard Howard resigned as president and GM of the speedway.

Together Smith and Wheeler began to implement plans for improvement and expansion of the speedway.[3]

In the following years, new grandstands and luxury suites were added along with modernized concessions and restrooms to increase the comfort for race fans. Smith Tower, a 135,000 square feet (12,500 m2), seven-story facility was built and connected to the grandstands in 1988. The tower houses the speedway corporate offices, ticket office, gift shop, leased offices and The Speedway Club, an exclusive dining and entertainment facility. The speedway became the first sports facility in America to offer year round living accommodations when 40 condominia were built overlooking turn 1 in 1984, twelve additional condominium units were later added in 1991.[3]

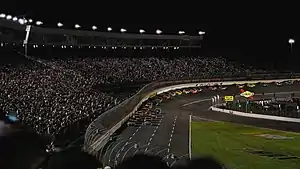

In 1992, Smith and Wheeler directed the installation of a $1.7 million, 1,200-fixture permanent lighting system around the track developed by Musco lighting. The track became the first modern superspeedway to host night racing, and was the largest lighted speedway until 1998 when lights were installed around the 2.500 mi (4.023 km) Daytona International Speedway. In 1994, Smith and Wheeler added a new $1 million, 20,000 square feet (1,900 m2) garage area to the speedway's infield.[3]

In 1995, 26-year-old Russell Phillips was killed in one of the most gruesome crashes in auto racing history.

From 1997 to 1999 the track hosted the IndyCar Series. On lap 61 of the 1999 race, a crash led to a car losing a tire, which was then propelled into the grandstands by another car. Three spectators were killed and eight others were injured in the incident. The race was canceled shortly after, and the series has not returned to the track since. The incident, along with a similar incident in July 1998 in a Champ Car race at Michigan International Speedway, led to new rules requiring cars to have tethers attached to wheel hubs to prevent tires from breaking away in a crash. Also following the crash, the catch fencing at Charlotte and other SMI owned tracks was raised from 15 ft (4.6 m) high with 3 ft (0.91 m) overhangs to 21 ft (6.4 m) with 6 ft (1.8 m) overhangs to help prevent debris from entering the stands.[7]

In February 1999, Lowe's bought the naming rights to the speedway, making it the first race track in the country with a corporate sponsor. Lowe's chose not to renew its naming rights after the 2009 NASCAR season.[8] The track reverted to its original name, Charlotte Motor Speedway, in 2010.[9]

In 2005, the surface of the track had begun to wear since its last repaving in 1994. This resulted in track officials diamond-grinding the track, a process known as levigation, to smooth out bumps that had developed. The ground surface caused considerable tire-wear problems in both of the NASCAR races that year. Both races saw a high number of accidents as a result of tire failure due to the roughness of the surface. In 2006, the track was completely repaved.[10]

Track president "Humpy" Wheeler retired following the Coca-Cola 600 on May 25, 2008, and was replaced by Marcus Smith.[11] At the end of 2008, the speedway reduced capacity by 25,000 citing reduced ticket sales. At the same time, the front stretch seats were upgraded from 18 in (46 cm) fold down seats to 22 in (56 cm) stadium style seats that were acquired from the recently demolished Charlotte Coliseum. On September 22, 2010, the speedway announced a partnership with Panasonic to install the world's largest high definition video board at the track.[12][13] The video board measures approximately 200 ft (61 m) wide by 80 ft (24 m) tall, containing over nine million LEDs and is situated between turns 2 and 3 along the track's backstretch. It has since been surpassed in size by the video board at Texas Motor Speedway.[14] The track demolished the Diamond Tower Terrace grandstand on the backstretch in 2014 to reduce the track's seating capacity to 89,000. Charlotte Motor Speedway reduced their seating capacity by 31% due to the continuing declining attendance.[15] This downfall of attendance has not only been felt at Charlotte Motor Speedway, but all throughout NASCAR, thus causing Daytona International Speedway to go through renovations, also reducing seating.[15][16]

Grandstand fatalities

On Saturday night, May 1, 1999, at the VisionAire 500K Indy Racing League race, as reported by IRL announcer Mike King, grandstands in the apex of Turn 1 were closed, but seats in Turns 1 and 2 past the apex were open. Seats outside of Turn 4 were also closed. When attendance grew beyond the 50,000 expected for the race, extra sections of stands were opened, and one of them was the section of track where the debris flew in Turn 4. Buddy Lazier was leading the race at the time of the caution for the Lap 62 crash involving Stan Wattles and John Paul Jr. when Wattles’ rear suspension failed, with the right rear wheel assembly hit by Paul, launching it into the grandstands. After pit stops, Greg Ray was leading the race when the race was abandoned. The race was canceled after 79 laps, and the IRL did not return.

Aftermath

That incident, and a previous incident in July 1998 in a Champ Car race at Michigan which also killed three spectators (that race was run to its finish), led to new rules requiring cars to have tethers attached to wheel hubs in an effort to prevent such incidents from happening again. New catch fencing was also invented, curved so debris could not sail as easily into the grandstands.

Bridge collapse

On May 20, 2000, fans were crossing a pedestrian bridge from the track to a nearby parking lot after that year's The Winston (NASCAR's all-star race). An 80-foot (24 m) section of the walkway fell onto a highway in Concord.[17] In total, 107 fans were injured at Lowe's Motor Speedway when the bridge dropped 17 feet (5.2 m) to the ground.[18] Nearly 50 lawsuits against the speedway resulted from the incident, with many being settled out of court. Investigators have said the bridge builder, Tindall Corp., used an improper additive to help the concrete filler at the bridge's center cure faster. The additive contained calcium chloride, which corroded the structure's steel cables and led to the collapse.[17] The incident is considered one of the biggest disasters in NASCAR history.[18]

Layouts

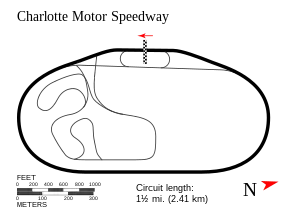

Quad oval

The main quad oval is 1.500 mi (2.414 km) long with turns banked at 24 degrees and the straightaways banked at 5 degrees. Currently, the configuration hosts the NASCAR Cup Series (NASCAR All-Star Race and Coca-Cola 600), Xfinity Series (Alsco Uniforms 300), and Truck Series (North Carolina Education Lottery 200). The quad oval is asymmetrical with turns 1 and 2 being 2400 ft long and turns 3 and 4 being 2040 ft long.[19]

Short oval

Inside the front stretch is a 0.250 mi (0.402 km) flat oval designed after Bowman Gray Stadium. The 1/4-mile track previously hosted the NASCAR Whelen Southern Modified Tour. Now it currently hosts the Summer Shootout Series and other events such as the Legends Million.

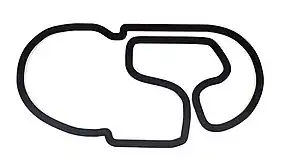

Road course / "Roval"

Contained within the main oval is a 2.280 mi (3.669 km) road course and a 0.600 mi (0.966 km) kart course. The autumn races for both the NASCAR Cup Series and the NASCAR Xfinity Series take place on the road course, promoted as a "Roval". The final version was announced on January 22, 2018. The layout combines the 1.500 mi (2.414 km) oval with the infield road-racing section over 17 turns.[20] In 2019, the Roval's backstretch chicane was redesigned, with an increase in width from 32 to 54 ft (9.8 to 16.5 m). The redesign requires heavier braking and a sharper entry, but allows better passing opportunities.[21][22] Chase Elliott is the winningest driver in the Cup Series Roval race, having won in 2019 and 2020. A. J. Allmendinger has the most wins in the Xfinity Series event, having won four straight from 2019 to 2022. Allmendinger also won the 2023 Bank of America Roval 400 for his first win on the Roval in the Cup Series.

zMAX Dragway

The zMAX Dragway is a state-of-the-art four-lane drag strip, located on 125 acres (0.51 km2) of speedway property across U.S. Highway 29 from the main superspeedway. It was built in 2008 involving a total of 1,876 workers and a combined 636,000 man hours. With 300 workers on site daily working an average 11-hour shift, a 13-month construction project turned into a 6-month one. At one point during construction, concern by nearby residents led Concord city council to rezone land the drag strip was being built on, preventing it from being built. Following the decision Smith threatened to close Charlotte Motor Speedway and build a track elsewhere in Metrolina.[23][24] When asked if he would go through with the threat Smith replied "I am deadly serious".[24] After a month of negotiations, the issue was settled and, instead of the speedway closing, Smith announced $200 million worth of improvements including road and highway improvements, as well as noise attenuation for the drag strip.[23] The drag strip officially opened on August 20, 2008, and a public open house was held a few days later. The first NHRA event was held September 11–14, 2008.[25]

The dragway features the first of two all-concrete, four-lane drag strips in the United States. (The track was the only four-lane track of its kind from 2008 until the spring of 2018, when renovations were completed at Las Vegas Motor Speedway, converting its dragstrip into a four-lane configuration.) The starting line tower is 34,000 square feet (3,200 m2) and includes 16 luxury suites, race control areas and a press box. Two grandstands, one on either side of the strip, can hold a combined 30,000 spectators. Twenty-four luxury suites with hospitality accommodations are located above the main grandstand. Two tunnels run underneath the strip to enhance fan mobility between the two grandstands.[26]

The Dirt Track

The Dirt Track at Charlotte[27] is a 1,300 ft (400 m) clay oval located across Highway 29 from the quad-oval speedway. The stadium-style facility, built in 2000, has nearly 14,000 seats and plays host to Dirt Late Models, Modifieds, Sprint Cars, Monster Trucks and the prestigious World of Outlaws World Finals.[3] In 2013, the track hosted the Global Rallycross Round 8.

Events

Current races

- NASCAR Cup Series:

- Coca-Cola 600 (1960–present)

- Bank of America Roval 400 (1960–present)

- NASCAR Xfinity Series:

- Alsco Uniforms 300 (1978–present)

- Drive for the Cure 250 (1973–present)

- NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series:

- North Carolina Education Lottery 200 (2003–present)

- ARCA Menards Series

- General Tire 150 (1996–2004, 2018–2019, 2021–present)

- NHRA Camping World Drag Racing Series

- Circle K 4 Wide Nationals

- Betway Nationals

- World of Outlaws

- Circle K/NOS Energy Drink Outlaw Showdown (NOS Energy Drink Sprint Cars)

- Bad Boy Off Road World Finals (NOS Energy Drink Sprint Cars, Morton Buildings Late Models, Super DIRTcar Series)

- INEX raceCeiver Legends Car Series/Bandoleros

- Bojangles Summer Shootout Series

- Winter Heat Series

- INEX Bandolero Nationals (2015, 2018)

- ChampCar Endurance Series

- 14-Hours of Charlotte

Former races

- AMA Superbike Championship (1977, 1980, 1991–1993)

- American Le Mans Series

- Grand Prix of Charlotte (2000)

- American Flat Track

- Don Tilley Memorial Charlotte Half-Mile (2015–2017)

- ASA National Tour

- Aaron's 99 (2004) - won by Reed Sorenson

- Can-Am (1978–1979)

- Champ Truck World Series[28] (2015)

- Fastrak Racing Series (2006–2010)

- IMSA GT Championship

- Grand Prix of Charlotte (1971, 1974, 1982–1986)

- IMSA SportsCar Championship

- Grand Prix of Charlotte (2020)

- INEX raceCeiver Legends Car Series/Bandoleros

- Legends All Star (2010–2013, 2015)

- Legend Car Dirt Nationals (2001)

- IROC (1996–1997)

- NASCAR Goody's Dash Series/IPOWER Dash Series (1975–1976, 1985–1988, 1997–2004)

- Lucas Oil Late Model Dirt Series (2005–2006)

- Monster Energy AMA Supercross (1996–1998)

- MXGP

- MXGP of Americas (2016)

- Mystik Lubricant's Terracross Championship (2014)

- NASCAR K&N Pro Series East

- All-Pro Auto Parts 300 (1987) – combination race with the NASCAR Xfinity Series, won by Harry Gant

- NASCAR Whelen Modified Tour

- Southern Slam 150 (2017) - won by Doug Coby

- NASCAR Sportsman Division (1989–1995)

- NASCAR Whelen Southern Modified Tour

- Southern Slam 150 (2010-2016, became a Whelen Modified Tour non-points event after the demise of the Southern Modified Tour)

- National Dirt Racing Association

- Crate Late Models (2010–2013)

- Modz Series (2011)

- Pirelli World Challenge (2000, 2007)

- Red Bull Global Rallycross (2012–2014)

- SCCA Formula Super Vee (1974, 1978–1982)

- Stadium Super Trucks (2016)[29]

- Super DIRTcar Series

- Eckerd 100 (2001–2005)

- Trans-Am Series (1981, 2000, 2022)

- TORC: The Off Road Championship

- Showdown in Charlotte (2014, 2016)

- USAC

- AMSOIL National Sprint Cars (2003–2005) – Dirt Track

- Honda National Midget Championship (1998) – Quarter Mile

- Indy Racing League

- VisionAire 500K (1997–1999)

- World of Outlaws Late Model Series

- WoO LM October Showdown

Other events

The facility is considered one of the busiest sports venues in the country, typically with over 380 events a year. Along with many races, the speedway also hosts the Charlotte Auto Fair twice a year, one of the nation's largest car shows. Movies and commercials have been filmed at the speedway, notably Days of Thunder, and it is a popular tourist stop and car testing grounds.[3] The facility also hosts several driving schools year-round, such as Richard Petty Driving Experience, where visitors have the opportunity to experience the speedway from a unique point-of-view behind the wheel of a race car.[30]

The feature of the April 2005 Food Lion Auto Fair at the speedway was a popular sculpture exhibition, Jim Gary's Twentieth Century Dinosaurs. It is a menagerie of Garysauruses, all life-sized, and constructed of automobile parts. A special tent housed the heavily attended exhibition and a huge Gary sculpture, over forty feet long, was displayed at the entrance to the raceway during the entire fair. H. A. "Humpy" Wheeler and the speedway then sponsored the funding for the traveling sculpture exhibition to be featured by Belk College of Business on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte where a self-guided tour of the campus-wide display was extended to the end of July.[31]

In 2006 the speedway hosted the world premiere of Pixar's 2006 film Cars.

American Idol season twelve auditions took place at the speedway from October 2–3, 2012.[32]

Since 2013, the annual Carolina Rebellion hard rock and heavy metal festival concert on the first weekend in May has been held at the Rock City Campgrounds located at the speedway. Bands such as Avenged Sevenfold, Kid Rock, Deftones, Disturbed, ZZ Top, Halestorm, Sevendust, Anthrax. Five Finger Death Punch, and All That Remains have played at Carolina Rebellion. The event was extended to three-day format in 2016, with 80,000 in attendance.[33]

Proposed football stadium

During the mid-1980s, there was a plan to build a football stadium on the frontstretch of the track with the goal of luring either an NFL or USFL team. The stadium would have held 76,000 and had temporary stands at both endzones and grandstand seating behind pit road that could have been lowered on hydraulic lifts for races and cost $12 million. There were two interested parties in bringing a professional football franchise to Charlotte, businessman George Shinn and Smith. By 1984, Shinn was in the running for a USFL franchise for Charlotte that would have played in the proposed stadium. In mid-March 1985, Bruton Smith announced that Charlotte Motor Speedway was in the market for an NFL team. After Smith demanded that the city of Charlotte pay for the project the plan collapsed.[34] Shinn eventually landed the NBA Charlotte Hornets and the NFL came to town in the form of the Carolina Panthers; however, the Panthers owner Jerry Richardson would go on to build his own stadium in Charlotte.

Track records

| Record | Year | Date | Driver | Car make | Time | Speed/Average speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NASCAR Cup Series | ||||||

| Qualifying | 2014 | October 9 | Kurt Busch | Chevrolet | 27.167 | 198.771 mph (319.891 km/h) |

| Race (600 miles) | 2016 | May 29 | Martin Truex Jr. | Toyota | 3:44:05 | 160.655 mph (258.549 km/h) |

| Race (500 miles) | 1999 | October 10 | Jeff Gordon | Chevrolet | 3:07:31 | 160.306 mph (257.987 km/h) |

| NASCAR Xfinity Series | ||||||

| Qualifying | 2005 | October 11 | Jimmie Johnson | Chevrolet | 28.763 | 187.735 mph (302.130 km/h) |

| Race (300 miles) | 1996 | May 25 | Mark Martin | Ford | 1:55:23 | 155.996 mph (251.051 km/h) |

| NASCAR Truck Series | ||||||

| Qualifying | 2014 | May 16 | Kyle Busch | Toyota | 29.384 | 183.773 mph (295.754 km/h) |

| Race (200 miles) | 2016 | May 21 | Matt Crafton | Toyota | 1:25:01 | 141.855 mph (228.293 km/h) |

| Indy Racing League | ||||||

| Qualifying | 1998 | July 24 | Tony Stewart | Dallara | 24.320[35] | 222.039 mph (357.337 km/h) |

| Race (312 mi (502 km)) | 1997 | July 26 | Buddy Lazier | Dallara | 1:55:29.224 | 162.096 mph (260.868 km/h) |

| Source:[36] | ||||||

| Record | Year | Date | Driver | Vehicle | Time | Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top Fuel | 2019 | Apr. 26 | Mike Salinas | Morgan Lucas Racing dragster | 3.687 | 327.43 mph (526.95 km/h) |

| Funny Car | 2017 | Apr.28 | Courtney Force | Camaro | 3.851 | 323.27 mph (520.25 km/h) |

| Mountain Motor Pro Stock | 2019 | Apr. 26 | JR Carr | Camaro | 6.240 | 225.79 mph (363.37 km/h) |

| Pro Stock Car | 2015 | Apr. 26 | Jason Line | Camaro | 6.455 | 214.48 mph (345.17 km/h) |

| Pro Stock Motorcycle | 2018 | Apr. 29 | Jerry Savoie | Suzuki | 6.765 | 195.73 mph (315.00 km/h) |

| Monster Truck[37] | 2012 | Mar. 17 | Randy Moore | Aaron's Outdoor Monster Truck | 96.80 miles per hour (155.78 km/h) |

NOTE: The track records listed for Top Fuel and Funny Car are in the 1,000 foot (304.8 meter) increment.

Lap records

As of May 2023, the fastest official race lap records at Charlotte Motor Speedway are listed as:

Notes

References

- ↑ "Seating Charts | Fan Info | Charlotte Motor Speedway". Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ↑ Tear it down: Charlotte track seating capacity shrinking by 31% Archived February 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Speedway History". Charlotte Motor Speedway. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ↑ Charlotte Observer timeline on Charlotte Motor Speedway Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Benyo, Richard (1977) SUPERSPEEDWAY: The Story Of NASCAR Grand National Racing Mason/Charter ISBN 0-88405-391-1 pp.71-6

- ↑ Benyo, SUPERSPEEDWAY, p. 76

- ↑ "Fatal Crash Prompts IRL Action". CBS News. CBS Interactive. Associated Press. May 18, 1999. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ Newton, David (January 23, 2010). "Standing room only? Not these days". Concord, North Carolina: ESPN. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ Long, Dustin (January 5, 2010). "New name for a track, new drivers and some rule changes". The Virginian-Pilot. Landmark Media Enterprises. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ Bowles, Tom (March 5, 2010). "Hard choices ahead if Kentucky Speedway joins Sprint Cup circuit". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on March 8, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ "NASCAR promoter Humpy Wheeler to retire after Coca-Cola 600". Autoweek.com. Crain Communications. May 20, 2008. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ↑ "TV is 30 percent larger than Cowboys'". ESPN. March 31, 2011. Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ↑ "Charlotte Motor Speedway and Panasonic Announce World's Largest HD Video Board". September 22, 2010. Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved September 22, 2010.

- ↑ "ABC Sports News". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- 1 2 "SRLY". SRLY. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ↑ Pockrass, Bob (December 11, 2014). "Tracks continue removing seats; how it could impact fans". Sporting News. Archived from the original on June 8, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- 1 2 Fryer, Jenna (July 5, 2006). "Judge rules against fans in Lowe's bridge collapse". ESPN News Services. Raleigh, North Carolina: ESPN Internet Ventures. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- 1 2 Boudin, Michelle (July 30, 2010). "10 years after NASCAR bridge collapse, injured man changing lives". Charlotte, North Carolina: WCNC-TV. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Speedway Facts". www.charlottemotorspeedway.com. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Charlotte Motor Speedway Reveals Faster, Tougher Roval Layout". charlottemotorspeedway.com. Speedway Motorsports, Inc. January 22, 2018. Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ↑ Utter, Jim (June 24, 2019). "Charlotte Roval's backstretch chicane gets a redesign". Motorsport Network. Archived from the original on October 1, 2019. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Charlotte Motor Speedway - Racing Circuits". Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- 1 2 "Lots of love (and $80M) keeps track in Concord". nascar.com. November 27, 2007. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- 1 2 Poole, David; Durhams, Sharif (October 3, 2007). "My way or no speedway, Bruton Smith tells city officials". The Charlotte Observer.

- ↑ "zMAX Dragway – A Year in Review". Charlottemotorspeedway.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ "zMAX Dragway @ Concord Fast Facts". zmax.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Dirt Track". Charlotte Motor Speedway. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Meritor Champ Truck World Series - Home". Archived from the original on May 20, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Stadium Super Trucks Added to TORC Charlotte Race". Off-Road. August 9, 2016. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- ↑ Charlotte Motor Speedway - Races Tracks - Richard Petty Driving Experience Archived April 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Drivepetty.com. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ↑ "Belk College notes passing of sculptor Jim Gary". uncc.edu. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ↑ Smith, Shannon (October 3, 2012). "'American Idol' auditions: day two in Charlotte". Tribune Broadcasting. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015 – via WGHP.

- ↑ "Carolina Rebellion to bring three days of rock". The News Herald. March 28, 2016. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Historical Motorsports Stories: Football at Charlotte Motor Speedway - Racing-Reference.info". racing-reference.info. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Charlotte". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Race Results at Charlotte Motor Speedway". Racingreference.info. Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ↑ Glenday, Craig (2014). Guinness World Records 2014. 2013 Guinness World Records Limited. pp. 171. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- 1 2 3 4 "Charlotte - Motorsport Database". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Trans Am Series Presented by Pirelli March 17 - 20 2022 Charlotte Motor Speedway TA XGT SGT GT Round 2 Official TA / GT Race Results" (PDF). March 20, 2022. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ↑ "NASCAR Cup 2022 Bank of America Roval 400 Race Statistics". Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ↑ "NASCAR Xfinity 2022 Bank of America Drive for the Cure 250 Race Statistics". Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- 1 2 "2020 MOTUL 100% Synthetic Grand Prix Race Official Results (1 Hours 40 Minutes)" (PDF). International Motor Sports Association (IMSA). October 11, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ↑ "NASCAR Cup 2018 Charlotte II". Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ↑ "NASCAR XFINITY 2018 Charlotte II". Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ↑ "1998 VisionAire 500K". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ↑ "NASCAR Cup 2017 Charlotte". Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ↑ "NASCAR XFINITY 2020 Charlotte". Archived from the original on May 29, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ↑ "2023 North Carolina Education Lottery 200 Race Statistics". Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "2000 Grand Prix of Charlotte". Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Charlotte 500 Kilometres 1984". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Can-Am Charlotte 1978". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- 1 2 "Charlotte 300 Kilometres IMSA GTO 1985". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Charlotte 500 Kilometres 1985". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Charlotte 300 Miles 1974". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Trans-Am Charlotte 1981". Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

External links

- Official site

- Map and circuit history at RacingCircuits.info

- Charlotte Motor Speedway race results at Racing-Reference

- Charlotte Motor Speedway Page on NASCAR.com

- Jayski's Charlotte Motor Speedway Page – Current and past Charlotte Motor Speedway Speedway news

- Richard Petty Driving Experience at Charlotte Motor Speedway