The Marquess of Santarém | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) Portrait of Dom Luís de Ataíde at Goa State Museum | |

| Governor and Viceroy of Portuguese India | |

| Monarch | Sebastian |

| In office 1568–1571 | |

| Preceded by | Antão de Noronha |

| Succeeded by | Diogo de Meneses |

| In office 1578–1581 | |

| Preceded by | António de Noronha |

| Succeeded by | Fernão Teles de Meneses |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1516 Kingdom of Portugal |

| Died | 10 March 1581 (aged 65) Goa, Portuguese India |

| Parents |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Portuguese Empire |

| Battles/wars | |

D. Luís de Ataíde, 1st Marquess of Santarém and 3rd Count of Atouguia (c. 1516 – March 10, 1581), was a Portuguese nobleman, military commander and statesman of the 16th century, who stood out for his military feats in the Portuguese State of India. He served as Viceroy of India for two non-subsequent terms (1568–1571 and 1578–1581).

In his first term in India, Dom Luís de Ataíde led military campaigns in the war of the League of the Indies that would probably be described today as a total war (a concept created in the 18th century, in opposition to the notion of limited war); for the Portuguese Empire had to use all of its available resources - military, economic, political and diplomatic - and also include operations involving or affecting civilians, in order to be able to resist a joint assault by the Indian potentates, with the purpose of expelling the Portuguese from their cities, forts and trading posts in the Indian Ocean.[1]

Early life

He was born in 1516, the second-born son of Dom Afonso de Ataíde by his wife Maria de Magalhães; and great-grandson of the 2nd count of Atouguia, Dom Martinho de Ataíde, by his second wife Filipa de Azevedo.[2]

Military service in the East and in Europe

He left for India for the first time in 1538, on the fleet's flagship that transported viceroy Dom Garcia de Noronha, his cousin. Later, under the government of Noronha's successor, governor Dom Estevão da Gama, he joined an expedition to the Red Sea, and - after the Battle of El Tor - he was formally knighted by da Gama in Saint Catherine's Monastery, at the foot of Mount Sinai, in April 1541.[3] This episode would become famous, considered one of the greatest feats of chivalry in history, later celebrated in Europe, with Emperor Charles V saying that he was "envious of those who had been armed as knights at the foot of Mount Sinai".[4]

After the arrival in Goa of a new governor, Martim Afonso de Sousa, Ataíde returned to Portugal, where he became the heir to his father's estates, as his eldest brother had meanwhile died in combat in the Portuguese possessions in Morocco.

Ambassador to the court of Charles V

In February 1547, King João III appointed him ambassador to the court of Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Empire.

He left Portugal on March 5 and arrived at the emperor's camp, located on the banks of the Elbe River in Saxony, on April 17 - that is, seven days before the battle that was to take place at Mühlberg.

On April 21, he was received by the emperor and went with him to mass. He told him of his desire to participate in the forthcoming battle against the Protestants and Charles V reacted by "expressing contentment ... for his intention to serve on the expedition".

Ataíde thus participated in the battle that resulted in one of the greatest military victories of Charles V - and a resounding defeat for the Lutherans of the Schmalkaldic League, which would lead to its subsequent dissolution. He stood out for his courage in combat, and the emperor rewarded him on the occasion by offering him a plate armour.

This combat experience was also an opportunity for Dom Luís de Ataíde to learn military techniques in land warfare, with the greatest specialists of his time, such as the emperor himself and the 3rd Duke of Alba - applied by a multinational army of about 25,000 men and 8,000 horsemen. Such knowledge, in conjunction with the practice of naval warfare which he had already gained in the East, would help build his reputation for high competence in military matters.[5]

At the beginning of 1548, he returned to Portugal, and years later, in 1555, he was confirmed by king João III as lord of the town of Atouguia, on the death of his father. He then occupied himself with the defense of his territory, that was a constant target of attacks by French corsairs.[6] And he was careful to stay away from the political struggles and intrigues that followed the death of king João III, concerning the regencies, first of Catarina of Austria and then of Cardinal Dom Henrique.

In 1567, in a clear sign of rapprochement to the royal court, he was appointed supervisor of the main Hospital in Lisbon. And, shortly after the new king Sebastian I effectively took over the government of Portugal, he was appointed 10th viceroy of India, in March 1568. He was granted enhanced powers in relation to his predecessors, including the right to decree death sentences and to provide entitlements in his own name instead of the King's.

Viceroy in India, first term (1568–1571)

He left Portugal on 7 April, in command of a fleet that included an unusually large number of men-at-arms, and arrived in Goa in October 1568.

Conquering ports and patrolling the seas

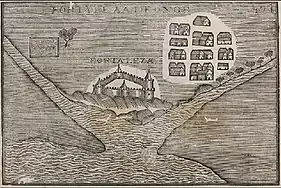

At first he maintained the policies of his predecessor. But, in the following year, he began to show his military side. Acting in order to prevent the sultan of Bijapur from taking possession of the city of Honnavar - which was a haven for pirates - in November 1569, at the head of an armada of 110 ships, he conquered that city, where the Portuguese later on built a fortress.

At the attack on Honavar, Ataíde sailed in a brigantine, accompanied by a famous musician playing a harp.[7] When the musician stopped playing as shots fell all around, Ataíde insisted that he continue the tune.[7] When he was requested to take better cover as his death could mean the failure of the expedition, he answered that if he were killed "there are men enough who are fit to succeed me".[7]

In 1570, writing to King Sebastian, Ataíde claimed success at patrolling the seas, for in that year only 2 ships had managed to escape Portuguese control, while traveling from Calicut to Mecca, compared to 16 or 18 ships in previous years.[8]

The War of the League of the Indies

Despite these initial military successes, a very serious threat remained, resulting from the fact that the Indian princes and potentates had allied themselves, in a large Islamic coalition, with the intention of expelling the Portuguese from the Indian Ocean (the Portuguese chronicler, António Pinto Pereira, called this coalition the "League of the kings of India", but the resulting conflict is usually referred to as the "War of the League of the Indies").[9]

The partition of the territories to be conquered had already been decided by the Indian coalition.

The sultan of Bijapur (called "Hidalcão" by the Portuguese) would march on Goa and take that city, and also Honnavar. The sultan of Ahmadnagar, Murtaza Nizam Shah I (whom the Portuguese called "Nizam Melek") would take Chaul, Daman and Vasai; and the Zamorin of Calicut was assigned to conquer the cities of Mangalor, Cananor, Chale, and Cochin.

Military victories over the Sultans of Bijapur and Amadanagar

The viceroy's defense strategy was based, from the very start of the combats, on seeking at all costs to keep the possession of the fortresses under threat of siege, with special emphasis on the strategic city of Chaul - which would prove to be decisive for the outcome, favorable to the Portuguese.

Surrounded in Goa by the large army of the Ali Adil Shah I (35 thousand horsemen, 60 thousand infantrymen and 2 thousand elephants, according to contemporary sources), Dom Luís de Ataíde was able to send military help to Chaul (despite the ecclesiastical opposition in Goa, which advised abandoning that fortress) and to carry out frequent counter-attacks.

In the defense of Goa, the viceroy introduced the unprecedented tactic of defending the city from 19 bases installed on its outer perimeter, with garrisons equipped with "large and smallish" artillery. He also involved the Catholic chapter of Goa in the defense of the city, arming hundreds of members of the Franciscan and Dominican religious orders and determined the formation of military companies of slaves and "indigenous Christians", under Portuguese command.[1]

Murtaza Nizam Shah I launched a major attack on Chaul on June 29, 1571, which was however successfully defended by Dom Francisco Mascarenhas - and this allowed for the signing of a truce the following month. And, in August 1571, after suffering heavy losses (8 thousand men, 4 thousand horses, 300 elephants and 150 artillery pieces), Ali Adil Shah I lifted the siege of Goa.[9]

In the final balance, with only 2,500 men-at-arms, Ataíde successfully faced the 5 sieges imposed on the Portuguese fortresses in India, in the period from 1570 to 1571. He had thus managed to overcome the last major political and military challenge faced by the Estado da Índia, before the arrival of new European opponents in the region, at the end of the 16th century.[3]

Ataíde delayed the signing of a formal peace with Ali Adil Shah I, in an attempt to impose tougher conditions on him. He left to his successor the job of concluding the negotiations and he departed from Goa on January 6, 1572, having completed his viceroyal mandate.

Return to Portugal (1572–1577)

Almost at the end of the return journey, he anchored on Terceira Island, from where he sent a letter to the King, telling him that, during his tenure in Goa, "the Moors" of the Sultanates of Bijapur and Ahmadnagar had lost 30,000 soldiers in the battles with the Portuguese; and that, in the end, a "honorable peace" had been negotiated with the enemies of the Kingdom of Portugal.

He arrived at the mouth of the Tagus river on July 3, and - after a short stay in Cascais - he solemnly entered Lisbon on the 21st.

King Sebastian had meanwhile decided that, taking into account the military victories in India, he would "grant Dom Luís de Ataíde the honor of accompanying him, in a procession through the streets of Lisbon", where he was positioned on the right side of the king, a place normally strictly reserved for members of the royal family or the house of Braganza.

The reception given by the Portuguese monarch to Dom Luís de Ataíde was truly "triumphal", as never before had a viceroy of India been received with such honors, on his return to the kingdom.[10]

After this royal reception, Ataíde would never fail to take advantage of his presence in Portugal in order to recall, whenever the opportunity arose, the services that had been rendered by his family to the Avis dynasty, since the start of the 15th century.

Thus, on the occasion of King Sebastian's stay in Ceuta, in August 1574, he honored his great-great-great-uncle Vasco Fernandes de Ataíde (the first Portuguese nobleman that died in combat, in the process of the Portuguese overseas expansion), with a tombstone in Latin commemorating his heroic death.[11] This initiative, laden with symbolism, and undoubtedly also taken with the intention of pleasing the monarch, helped to reinforce his position, in the context of the fierce disputes among the most important nobles of the court, trying to gain influence on the very young king.

Due to his military experience in Europe and India, he was appointed by the King to head a planned military expedition to Morocco, which would later end in the military disaster of Alcácer Quibir. But the King changed his mind, and decided to personally assume the leadership of the expedition.[12] As a compensation, Ataíde was again sent to India as Viceroy and he left Lisbon, headed for Goa, on 16 October 1577.

The title of Count of Atouguia, as the 3rd holder in the Ataíde family, was granted to him by a decree from the king on September 4, 1577. This was seen at the time not just as a redress given to him by the King, for having removed him from the leadership of the military expedition to Morocco, but also as a just reward for the services he had rendered during his first mandate as viceroy in India.

Second term in India (1578–1581)

He kept winter quarters in Mozambique, where he awaited the arrival of the last fleet that left Portugal in 1578 - in which the famous Jesuit Matteo Ricci was traveling - and arrived in Goa on August 20, 1578.

In the beginning, he battled the forces of Ali Adil Shah I, but he was soon able to negotiate a peace treaty with him, on August 11, 1579 - on favorable terms, which included the return to the Portuguese of the island of Salsette (today, part of the city of Mumbai).

Donation of the Kingdom of Kotte to the Portuguese monarch (1580)

He also dedicated his attention to the Portuguese interests in the island of Ceylon, giving them priority in the allocation of military resources - which were not enough to help all the vast possessions of the Estado da Índia.

He thus considered Ceylon more central to the Portuguese position in the East than the presence in other places equally in need of military support, such as Aceh. It was during the second term of Ataíde, in 1580, that the King of Kotte, Dom João Dharmapala, bequeathed his kingdom to the King of Portugal,[13] a fundamental decision that would later serve to legitimize many decades of Portuguese sovereignty and territorial dominion in a large part of Ceylon.[14]

Nearly before his death, Ataíde received as a gift from Fernão Teles de Meneses (who would succeed him in the government of Goa), the famous posthumous portrait of Luís de Camões, dated from Goa, year 1581.[15]

Marquess of Santarém

Marquis of Santarém was a title created by a secret decree, in 1580, by King Filipe I, to be granted to Dom Luís de Ataíde, on the assumption that he would accept proclaiming the Habsburg monarch as sovereign, in the Estado da Índia.

The decree was carried by the newly appointed viceroy, Dom Francisco Mascarenhas, but it ultimately didn't produce legal effects - because Mascarenhas, who left Lisbon on April 8, only arrived in India in September 1581, six months after the death of Dom Luís de Ataíde, in Goa.

The concession of this title was very meaningful, for it would place Ataíde in the position of the fifth most important aristocrat of the kingdom of Portugal, after the Dukes of Bragança and Aveiro and the Marquises of Vila Real and Ferreira - which clearly demonstrates the importance that Filipe I attributed to obtaining Ataíde's support for his proclamation as sovereign in Portuguese India.[16]

Death and stance on the succession crisis of 1580

He died on March 10, 1581, at the age of 65, shortly after having received news of the aftermath of the military disaster at Alcácer Quibir and the death of the Cardinal-king Henry.

But he probably never got to know about the aftermath of the Battle of Alcântara and the proclamation of Philip I as king of Portugal. One of the last letters written by Ataíde, dated October 1580 and addressed to the Council of governors of the kingdom, insists above all on his desire to return to Portugal, where he needed to ensure the succession of the house of the counts of Atouguia; it is thus not possible to corroborate reports from later chroniclers, according to which he tended to sympathize with the pretender Dom António, Prior of Crato.

The fact that some of his closest relatives, such as his nephews Lopo de Brito (who should not be confused with his grandfather and namesake, Lopo de Brito, 2nd captain of Ceylon) and Cristóvão de Brito, supported Dom António (they fought for him and died in the battle of Alcântara), is not enough to conclude that Ataíde's political position was identical.[17]

A sentence attributed to him shortly before his death ("I die when everything is against Portugal") is not mentioned in 16th century sources, and - if it was actually uttered - could be interpreted as mere resignation in the face of developments in the distant kingdom, not susceptible to be influenced from Goa.

Furthermore, Ataíde was well acquainted with the powerful armies of Charles V, on whose side he had fought as a young man, and he had met the Emperor's son, Philip II of Spain (later to become also Philip I of Portugal) and his military commander, the 3rd Duke of Alba. It thus does not seem very plausible that - under the hypothesis, not proven, that he was aware of the outcome of the battle of Alcântara - he would believe in the likelihood of a military victory by the pretender Dom António, against such formidable opponents.

His tomb is today at the Church of Santa Casa da Misericórdia, in Peniche.[18]

Marriages and succession

He married three times, with no surviving generation.

According to contemporary sources, he also had two illegitimate offspring, which he did not legitimize.[19]

Succession to his estates and titles

The title of count of Atouguia would later pass to the descendants of a paternal aunt of Dom Luís de Ataíde, Dona Isabel da Silva de Ataíde, who was married to Simão Gonçalves da Câmara, 'the Magnificent', donatary of the island of Madeira.

The son of this marriage was Luís Gonçalves de Ataíde, who married Violante da Silva, daughter of Francisco Carneiro, 2nd donatary of Ilha do Príncipe.

Dom João Gonçalves de Ataíde, who would inherit the title as 4th Count of Atouguia, was their firstborn son.

The succession of the title and house of Atouguia would thus not follow the line closest to the primogeniture - that is, to the descendants of the marriage of a sister of Dom Luís de Ataíde, Helena de Ataíde, with Tristão da Cunha (grandson of his namesake, Tristão da Cunha, the famous navigator), who a few generations later would be granted the titles of Count of Pontével, Count of Povolide and Count of Sintra.

Thus were the personal wishes and preferences of Dom Luís de Ataíde fulfilled. For he many times expressed his desire for the house of Atouguia to eventually pass on to the descendants of a collateral branch of the Câmara family, counts of Calheta, who were then very influential in the royal court, rather than to the Cunha family - who despite representing a more ancient lineage, dating back to the foundation of the Kingdom of Portugal, didn't have any member who held a nobility title in Portugal, at that time (the many titled members of the Cunha family were all from branches who had emigrated from Portugal to Castille, since the Middle Ages).[20]

Legacy

In literature

Luís de Camões dedicated a sonnet to him, with the title "A D. Luís de Ataíde, Vizo-Rei", which, curiously, ends with the same word ("inveja", meaning envy) with which the poet concludes his epic poem "Os Lusíadas":[21]

(...)

what gives you more name in the world,

is to vanquish, my lordship, in the friendly Kingdom,

so much ingratitude, so much envy!

(Luís de Camões, Sonnets, "A D. Luís de Ataíde, Vizo-Rei")

Other distinguished authors, such as the humanist André de Resende[22] and José Agostinho de Macedo,[23] also dedicated works to him.

Namesakes

In Portugal, the cities of Porto,[24] Barreiro and Peniche, as well as a parish in the municipality of Sintra, have streets named after him. His name was also given to a group of schools in Peniche.[25]

References

- 1 2 Feio, Gonçalo Maria Duarte Couceiro (2014). O ensino e a aprendizagem militares em Portugal e no Império, de D. João III a D. Sebastião : a arte portuguesa da guerra (doctoralThesis thesis). Pages 135-138

- ↑ Braga, Nuno Luís de Vila-Santa (2013). A Casa de Atouguia, os Últimos Avis e o Império. Dinâmicas entrecruzadas na carreira de D. Luís de Ataíde (1516-1581) (in Portuguese). Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. p. 444. hdl:10362/12269.

- 1 2 Matos, J. Semedo de (2012). "A marinha de D. Sebastião – O Vice-Rei D. Luís de Ataíde»". Revista da Armada n.º 459.

- ↑ Monteiro, Saturnino (2014). "Mar Vermelho (1541) - Batalha de El Tor". Batalhas e Combates da Marinha Portuguesa - Volume III - Do Brasil ao Japão 1539-1579 (in Portuguese). Saturnino Monteiro and Livraria Sá da Costa Editora. p. 42.

Emperor Charles V himself would later declare that he was envious of those who had been armed as knights at the foot of Mount Sinai. And on the tomb of Dom Estevão da Gama it was engraved as an epitaph: 'He who armed knights on Mount Sinai'

- ↑ Boxer, Charles R. (1973). "The Portuguese seaborne empire, 1415-1825 | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. pp. 302–303. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ↑ "Carta de D. Luís de Ataíde expondo ao rei a necessidade de se desfazer a cisterna das Berlengas aonde os franceses iam fazer aguadas e roubarem embarcações, que estes piratas eram os franceses que vindo a Lisboa vender trigos, faziam na retirada semelhantes danos. - Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo - DigitArq". digitarq.arquivos.pt. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- 1 2 3 Robert Kerr: A General History of Voyages and Travels to the End of the 18th Century, Volume 6, p. 450.

- ↑ Braudel, Fernand (1995). "The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean world in the age of Philip II | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. p. 555. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- 1 2 Pereira, António Pinto (1987). História da India no tempo em que a governou o Visorei Dom Luís de Ataíde: reprodução em fac-símile do exemplar com data de 1617 da Biblioteca da INCM (in Portuguese). Impr. Nacional-Casa da Moeda. pp. 143, 149.

- ↑ Cruz, Maria Augusta Lima (2009). "D. Sebastião | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. p. 209. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ↑ Braamcamp Freire, Anselmo (1921). Brasões da Sala de Sintra, Livro Primeiro. Robarts - University of Toronto. Coimbra : Imprensa da Universidade. p. 84.

- ↑ Ramos, Rui; Sousa, Bernardo Vasconcelos e; Monteiro, Nuno Gonçalo (2014-07-29). História de Portugal. A Esfera dos Livros. p. 264.

- ↑ Disney, A. R. "A history of Portugal and the Portuguese empire : from beginnings to 1807. Volume 2, The Portuguese empire | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. p. 166. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ↑ Thomaz, Luís Filipe (2018). "L'expansion portugaise dans le monde, XIV-XVIIIe siècles : les multiples facettes d'un prisme | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. pp. 181–182. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ↑ Le Gentil, Georges (1995). "Camões l'oeuvre épique et lyrique | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. p. 33. Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ↑ Couto, Diogo do. Ásia, Década X, Parte I, Capítulo IX (PDF). Biblioteca Nacional Digital (Portugal).

- ↑ Sousa, D. António Caetano de (1749). História Genealógica da Casa Real Portuguesa, Tomo XII, Parte I. Biblioteca Nacional Digital (Portugal). p. 431.

- ↑ "Monumentos. Igreja da Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Peniche". www.monumentos.gov.pt (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-02.

- ↑ Campos, op. cit., p. 85

- ↑ Braamcamp Freire, Anselmo (1921). Brasões da Sala de Sintra, Livro Primeiro (in Portuguese). Robarts - University of Toronto. Coimbra: Coimbra : Imprensa da Universidade. pp. 162–165.

[The Cunhas were titled] in Castille where they were created Counts of Valencia de Don Juan since 1397 ... from [the Cunhas] proceeded the Marquises of Vilhena, Dukes of Escalona, counts of Xiqueña...The Dukes of Ossuna, counts of Ureña... the Dukes of Najera, Counts of Requeña, the Marquises of Escalona and others.

- ↑ Camões, Luís de. "Domínio Público - Pesquisa Básica. Sonetos de Camões". www.dominiopublico.gov.br (in Portuguese). p. 51 (164). Retrieved 2023-07-02.

o que vos dá mais nome inda no mundo é vencerdes, Senhor, no Reino amigo, tantas ingratidões tão grande enveja

- ↑ Pereira, Belmiro Fernandes (1993). "A fama portuguesa no ocaso do império: A divulgação europeia dos feitos de D. Luís de Ataíde. André de Resende, "Illvstrissimo Domino Lvdovico Athaidio", Roma, 1575" (PDF).

- ↑ Macedo, José Agostinho de; Faria e Sousa, Manuel de (1823). D. Luiz d'Ataide, ou, A tomada de Dabul: drama heroico: o assumpto he tirado da Asia Portugueza de Manoel de Faria e Sousa, tom. II. parte III. &c. Tomada de Dabul. Lisboa: Na Imprensa Nacional.

- ↑ "R. Dom Luís de Ataíde · Porto, Portugal". R. Dom Luís de Ataíde · Porto, Portugal. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ↑ "Agrupamento de Escolas D. Luís de Ataíde". www.cm-peniche.pt (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-07-05.

.svg.png.webp)