Ludovic Halévy | |

|---|---|

Ludovic Halévy early in his career | |

| Born | 1 January 1834 Paris, France |

| Died | 7 May 1908 (aged 74) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Author |

| Children | Élie and Daniel |

| Parents | Léon Halévy Alexandrine Lebas |

| Relatives | Lucien-Anatole Prévost-Paradol (half-brother) Élie Halévy (paternal grandfather) Louis-Hippolyte Lebas (maternal grandfather) Fromental Halévy (paternal uncle) |

| Signature | |

| |

Ludovic Halévy (1 January 1834 – 7 May 1908) was a French author and playwright, best known for his collaborations with Henri Meilhac on Georges Bizet's Carmen and on the works of Jacques Offenbach.

Biography

Ludovic Halévy was born in Paris. His father, Léon Halévy (1802–1883), was a civil servant and a clever and versatile writer, who tried almost every branch of literature—prose and verse, vaudeville, drama, history—without, however, achieving decisive success in any. His uncle, Fromental Halévy, was a noted composer of opera; hence the double and early connection of Ludovic Halévy with the Parisian stage. His father had converted from Judaism to Christianity prior to his marriage with Alexandrine Lebas, daughter of a Christian architect.

At the age of six, Halévy might have been seen playing in that Foyer de la danse with which he was to make his readers so familiar, and, when a boy of twelve, he would often, on a Sunday night, on his way back to the Collège Louis le Grand, look in at the Odéon, where he had free admittance, and see the first act of the new play. At eighteen he joined the ranks of the French administration and occupied various posts, the last being that of secrétaire-rédacteur to the Corps Législatif. In that capacity, he enjoyed the special favour and friendship of the famous duke of Morny, then president of that assembly.

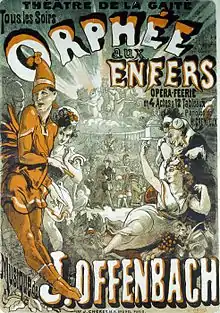

In 1865, Ludovic Halévy's increasing popularity as an author enabled him to retire from the public service. Ten years earlier, he had become acquainted with the musician Offenbach, who was about to start a small theatre of his own in the Champs-Élysées, and he wrote a sort of prologue, Entrez, messieurs, mesdames, for the opening night. Other little productions followed, Ba-ta-clan being the most noticeable among them. They were produced under the pseudonym of Jules Servières. The name of Ludovic Halévy appeared for the first time on the bills on 1 January 1856. Soon afterwards, the unprecedented run of Orphée aux enfers, a musical parody, written in collaboration with Hector Crémieux, made his name famous. In the spring of 1860, he was commissioned to write a play for the manager of the Variétés in conjunction with another vaudevillist, Lambert-Thiboust.

The latter having abruptly retired from the collaboration, Halévy was at a loss how to carry out the contract, when on the steps of the theatre he met Henri Meilhac (1831–1897), then comparatively a stranger to him. He proposed to Meilhac the task rejected by Lambert Thiboust, and the proposal was immediately accepted. Thus began a connection which was to last over twenty years, and which proved most fruitful both for the reputation of the two authors and the prosperity of the minor Paris theatres. Their joint works may be divided into three classes: the operettas, the farces, the comedies. The opérettes afforded excellent opportunities to a gifted musician for the display of his peculiar humour. They were broad and lively libels against the society of the time, but savoured strongly of the vices and follies they were supposed to satirize. Amongst the most celebrated works of the joint authors were La belle Hélène (1864), Barbe-bleue (1866), La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867), La Périchole (1868), and Le Réveillon, which became one of the sources of Johann Strauss's operetta Die Fledermaus.

After 1870, the vogue of parody rapidly declined. The decadence became still more apparent when Offenbach was no longer at hand to assist the two authors with his quaint musical irony, and when they had to deal with interpreters almost destitute of singing powers. They wrote farces of the old type, consisting of complicated intrigues, with which they cleverly interwove the representation of contemporary whims and social oddities. They generally failed when they attempted comedies of a more serious character and tried to introduce a higher sort of emotion. A solitary exception must be made in the case of Froufrou (1869), which, owing perhaps to the admirable talent of Aimée Desclée, remains their unique Succès de larmes. During this period, they wrote the libretto to Carmen but it was a sideshow to their other work.

Meilhac and Halévy will be found at their best in light sketches of Parisian life, Les Sonnettes, Madame attend Monsieur, Toto chez Tata and Le Roi Candaule (the title of the last is derived from the Classical Greek account of the semi-legendary King Candaules). In that intimate association between the two men who had met so opportunely on the perron des variétés, it was often asked who was the leading partner. The question was not answered until the connection was finally severed and they stood before the public, each to answer for his own work. It was then apparent that they had many gifts in common. Both had wit, humour, observation of character. Meilhac had a ready imagination, a rich and whimsical fancy; Halévy had taste, refinement and pathos of a certain kind. Not less clever than his brilliant comrade, he was more human.

Of this he gave evidence in two delightful books, Monsieur et Madame Cardinal (1873) and Les Petites Cardinal, in which the lowest orders of the Parisian middle class are faithfully described. The pompous, pedantic, venomous Monsieur Cardinal will long survive as the true image of sententious and self-glorifying immorality. M. Halévy's peculiar qualities are even more visible in the simple and striking scenes of the Invasion, published soon after the conclusion of the Franco-German War, in Criquette (1883) and The Abbot Constantine (1882), two novels, the latter of which went through innumerable editions. Émile Zola had presented to the public an almost exclusive combination of bad men and women; in L'Abbé Constantin all are kind and good, and the change was eagerly welcomed by the public. Some enthusiasts robustly maintain that the Abbé will rank permanently in literature by the side of the equally chimerical Vicar of Wakefield. At any rate, it opened for M. Ludovic Halévy the doors of the Académie française, to which he was elected in 1884.

Halévy remained an assiduous frequenter of the Academy, the Conservatoire, the Comédie Française, and the Society of Dramatic Authors, but, when he died in Paris on 7 May 1908, he had produced practically nothing new for many years.

His last romance, Kari Kari, appeared in 1892. His diary was published in book form in 1935 as well as serially in the pages of the Revue des Deux Mondes in 1937–38.

Filmography

- Films based on Die Fledermaus (The operetta Die Fledermaus is based on the play Le Reveillon)

- Frou-Frou, directed by Eugene Moore (1914, based on the play Frou-Frou)

- Bettina Loved a Soldier, directed by Rupert Julian (1916, based on the novel The Abbot Constantine)

- A Hungry Heart, directed by Émile Chautard (1917, based on the play Frou-Frou)

- Frou-Frou, directed by Alfredo De Antoni (Italy, 1918, based on the play Frou-Frou)

- Fanny Lear, directed by Robert Boudrioz and Jean Manoussi (France, 1919, based on the play Fanny Lear)

- Frou-Frou, directed by Otto Rippert (Germany, 1922, based on the play Frou-Frou)

- Frou-Frou, directed by Guy du Fresnay (France, 1924, based on the play Frou-Frou)

- The Abbot Constantine, directed by Julien Duvivier (France, 1925, based on the novel The Abbot Constantine)

- So This Is Paris, directed by Ernst Lubitsch (1926, based on the play Le Reveillon)

- The Abbot Constantine, directed by Jean-Paul Paulin (France, 1933, based on the novel The Abbot Constantine)

- La Vie parisienne, directed by Robert Siodmak (France, 1936, based on the operetta La Vie parisienne)

- Parisian Life, directed by Robert Siodmak (English version, 1936, based on the operetta La Vie parisienne)

- The Toy Wife, directed by Richard Thorpe (1938, based on the play Frou-Frou)

- Tricoche and Cacolet, directed by Pierre Colombier (France, 1938, based on the play Tricoche et Cacolet)

- La Goualeuse, directed by Fernand Rivers (France, 1938, based on the play La Goualeuse)

- Les Petites Cardinal, directed by Gilles Grangier (France, 1951, based on the novel Les Petites Cardinal)

- Sköna Helena, directed by Gustaf Edgren (Sweden, 1951, based on the operetta La belle Hélène)

- Die schöne Helena, directed by Axel von Ambesser (West Germany, 1975, TV film, based on the operetta La belle Hélène)

- Parisian Life, directed by Christian-Jaque (France, 1977, based on the operetta La Vie parisienne)

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Halévy, Ludovic". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- The Théâtre of MM. Meilhac and Halévy was published in 8 vols. (1900–1902).

External links

Works by or about Ludovic Halévy at Wikisource

Works by or about Ludovic Halévy at Wikisource- Works by Ludovic Halévy at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ludovic Halévy at Internet Archive

- Works by Ludovic Halévy at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- JewishEncyclopedia