Ludwig Ross | |

|---|---|

Ludwig Ross, photographed in later life | |

| Born | 22 July 1806 Bornhöved, Holstein, Denmark |

| Died | 6 August 1859 (aged 53) |

| Occupation | Archaeologist |

| Known for | Ephor General of Antiquities of Greece; restoration of the Temple of Athena Nike. |

| Title | Ephor General (1834–1836) |

| Spouse |

Emma Schwetschke (m. 1847) |

| Relatives | Charles Ross (brother) |

| Academic background | |

| Education | Christian-Albrechts-Universität, Kiel |

| Doctoral advisor | Gregor Wilhelm Nitzsch |

| Academic work | |

| Institutions |

|

| Notable students | Panagiotis Efstratiadis |

| Signature | |

| |

Ludwig Ross (22 July 1806 – 6 August 1859) was a German classical archaeologist. He is chiefly remembered for the rediscovery and reconstruction of the Temple of Athena Nike in 1835–1836, and for his other excavation and conservation work on the Acropolis of Athens. He was also an important figure in the early years of archaeology in the independent Kingdom of Greece, serving as Ephor General of Antiquities between 1834 and 1836.

As a representative of the Bavarocracy – the dominance by northern Europeans, especially Bavarians, of Greek government and institutions under the Bavarian King Otto of Greece – Ross attracted the enmity of the native Greek archaeological establishment. He was forced to resign as Ephor General over his delivery of the Athenian "Naval Records", a series of inscriptions first unearthed in 1834, to the German August Böckh for publication. He was subsequently appointed as the first professor of archaeology at the University of Athens, but lost his post as a result of the 3 September 1843 Revolution, which removed most non-Greeks from public service in the country. He spent his final years as a professor in Halle, where he argued unsuccessfully against the reconstruction of the Indo-European language family, believing the Latin language to be a direct descendant of Ancient Greek.

Ross has been called "one of the most important figures in the cultural revival of Greece."[1] He is credited with creating the foundations for the science of archaeology in independent Greece, and for establishing a systematic approach to excavation and conservation in the earliest days of the country's formal archaeological practice. His publications, particularly in epigraphy, were widely used by contemporary scholars. At Athens, he educated the first generation of natively trained Greek archaeologists, including Panagiotis Efstratiadis, one of the foremost Greek epigraphers of the 19th century and a successor of Ross as Ephor General.

Early life

Ross was born on 22 July 1806 in Bornhöved in Holstein, then ruled by the Kingdom of Denmark.[2] His paternal grandfather, a doctor, had moved from northern Scotland to Hamburg around 1750.[3] His father, Colin Ross, married Juliane Auguste Remin.[4] When Ludwig was four years old, his father moved the family to the Gut Altekoppel estate in Bornhöved, which he managed and later acquired.[5] Their five sons and three daughters[6] included Ludwig's younger brother, the painter Charles Ross.[2] Ludwig, like Charles,[7] campaigned for Holstein's independence from Denmark.[8] He did not consider himself Danish, and has generally been counted as German in modern scholarship.[9]

Ross grew up in Kiel and Plön.[10] In 1825,[11] he enrolled as a student at the Christian-Albrechts-Universität in Kiel. He began to study medicine, zoology and anthropology,[1] but eventually settled upon classical philology.[12] His teachers at Kiel included the theologian August Twesten,[11] the historian Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann,[11] and the classical scholar Gregor Wilhelm Nitzsch. He was also taught by the classicist Johann Matthias Schultz,[12] whose lectures focused largely on Greek and Roman literature, including the Greek playwrights Aeschylus, Sophocles and Aristophanes, as well as philosophical studies of Cicero and Lucretius.[12] While at Kiel, Ross met his friend and future travelling companion, the philologist Peter Wilhelm Forchhammer,[13] and befriended Otto Jahn, later known as a historian of ancient Greek and Roman pottery.[14]

Ross graduated on 16 May 1829[11] with a Ph.D. on Aristophanes's play Wasps,[10] supervised by Nitzsch. He made an unsuccessful application for a scholarship from the "Fund for the Public Benefit" (Danish: Fonden ad usos publicos),[1] administered on behalf of the King of Denmark, to travel in Greece.[1] After his rejection, he worked as a private tutor in Copenhagen.[10] His employer, the merchant Friedrich Gottshalck, would later be named the Greek consul to Denmark in 1835.[9]

Ross applied again to the "Fund for the Public Benefit", with Nitzsch's support,[15] in October 1830; he was accepted the following February. The fund provided him with an annual income of 600 rigsdaler (approximately twice a skilled worker's annual wage) for two years.[16] Also in 1831, he published his first scholarly work, a short history of the Duchy of Schleswig-Holstein.[11] Ross's letters of this period to Nitzsch reveal his intention to continue his studies of Aristophanes, and to publish academic work to build his scholarly reputation.[15] Ross spent nine months in Leipzig, beginning in the autumn of 1831, living with the school headmaster Karl Hermann Funkhaenel and attending lectures on Greek culture. On 23 May 1832,[17] he left to make his way to Greece,[10] travelling overland to Munich, Salzburg[1] and Trieste before boarding a Greek ship, the Etesia,[18] for Nafplion on 11 July.[11]

Archaeological career in Greece (1832–1843)

Ross arrived in Greece on 22 July [O.S. 10 July] 1832,[1][lower-alpha 1] two weeks before the National Assembly confirmed the appointment of Otto of Bavaria as King of Greece.[20] He was made deputy curator of antiquities at the Archaeological Museum of Nafplion, then capital of Greece, in 1832,[10] and was received by the Greek National Assembly in the city on 8 August [O.S. 27 July], presenting them with a lithograph of Otto which he had brought with him from Trieste.[21]

Ross travelled to the Mycenaean site of Tiryns on 12 August [O.S. 31 July]. On 22 August [O.S. 10 August], he sailed to the island of Aegina, on the way to Athens, in the company of three British artists and John Black, an English civil servant married to Teresa Makri, known as the inspiration for Lord Byron's "Maid of Athens".[17] Ross's first visit in the city was to the home of Kyriakos Pittakis, Black's brother-in-law,[22] a self-taught archaeologist who would be appointed "custodian of the antiquities in Athens" a few weeks later.[23]

Otto arrived in Greece at Nafplion on 6 February [O.S. 25 January] 1833.[24] Ross travelled to meet him with Forchhammer, who had joined him in Greece the preceding October, and the architects Eduard Schaubert and Stamatios Kleanthis. The party met Otto within a few months of their own arrival, a few days after the king's, and travelled widely around nearby archaeological sites such as Epidauros, Tiryns and Argos.[25]

Like many German archaeologists and scholars,[26] Ross found favour with the young king,[27] and Ross would later accompany Otto on archaeological travels around Greece.[28] Ross had been expected to leave Greece in 1833, having unsuccessfully applied in 1832 for an extension of his travel scholarship, and subsequently applied successfully in May 1833 for 200 rigsdaler to help pay for his journey back to Germany. In June 1833, the Bavarian architect Adolf Weissenberg was appointed as ephor with overall responsibility for Greek antiquities.[29] Shortly afterwards, Ross was offered a post as antiquary to the Bavarian government, but refused it as he did not wish to serve under Weissenberg. Ross subsequently accepted the Greek government's offer, in November 1833, of the post of "sub-ephor" (Greek: ὑποέφορος) of antiquities for the Peloponnese, alongside Pittakis for the rest of mainland Greece and Ioannis Kokkonis for Aegina. All three reported to Weissenberg.[30] During his tenure as sub-ephor, Ross lived in Nafplion and kept in regular contact with Otto's regent, Josef Ludwig von Armansperg, to whom he wrote about his dissatisfaction with the Greek government, the dirtiness of Nafplion's streets and the quality of its housing.[31]

Ross organised a series of sporting competitions, similar to the ancient Olympic and Isthmian Games, on 4 March 1833,[32] and encouraged the Greek government, through the royal family, to issue an 1837 decree re-establishing the Olympic Games in Pyrgos.[32] In January 1834, he travelled to Sparta, Mantineia and Tegea with Christian Tuxen Falbe, the Danish consul-general in Greece, who complained beforehand to the Danish prince Christian Frederik that Ross's "zeal ... to keep everything for the state" would make it impossible for him to acquire any artefacts for his own collection. Afterwards, Falbe confirmed to Christian Frederik that he had indeed secured almost nothing, thanks to Ross's consistency in acquiring antiquities for the state, and the state's own insistence upon bringing objects in private hands into its own collections.[9] Ross also carried out excavations at Menelaion, a sanctuary near Sparta dedicated to the hero Menelaus and to Helen of Troy.[33] In January 1834, he excavated the site of ancient Tegea in Arcadia, before travelling throughout Arcadia and Elis, including a small-scale excavation at Megalopolis and visits to Lykosoura and the Temple of Apollo at Bassae.[34] In 1834, he assisted with the planning of the modern city of Sparta.[35]

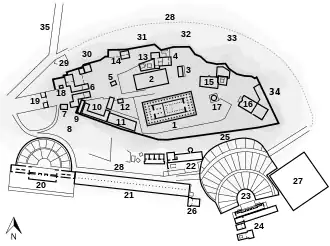

Work on the Acropolis of Athens (1834–1836)

In July 1834, the architect Leo von Klenze arrived in Athens to advise Otto on the development of the city. Klenze suggested that the Acropolis, which was at that point a military fortress occupied by Bavarian troops, should be demilitarised and designated an archaeological site. A royal decree to this effect was issued on 30 August [O.S. 18 August].[37] Weissenberg's reputed lack of interest in antiquities, as well as his political opposition to Armansperg,[38] led to his dismissal from office in September. On Klenze's recommendation,[39] Ross was given the title of Ephor General of Antiquities, with charge of all archaeology in Greece, on 10 September [O.S. 29 August], which included direct responsibility for the Acropolis.[40] He was paid a salary of 3,000 drachmas: a comfortable wage at a time when manual workers earned an average of 175 drachmas per year.[41] Ross's control of the Acropolis passed over Pittakis, who had been serving since 1832 as the unpaid "custodian of the antiquities in Athens",[42] and into whose sub-ephorate Athens fell by the arrangement of 1833.[30] In Athens, Ross worked mostly alongside architects from northern Europe, particularly the Prussian Schaubert, who was made Greece's chief architect in 1834;[43] the Danish Christian Hansen, who replaced the Greek Kleanthis on the latter's resignation, shortly after work began;[44] and the Dresden native[45] Eduard Laurent.[39] The dominance of non-Greek scholars in the excavation and conservation of Greek monuments provoked resentment from the native Greek intelligentsia, and animosity between Pittakis and Ross.[26]

Tension existed between the Greek state's aim of conserving Athens's ancient monuments, the Acropolis's role as a military fortification, and the needs of the expanding city. Klenze had envisaged that the area around the site would be kept clear of buildings, creating an "archaeological park": the pressure on housing created by a growing population, as well as the generally chaotic nature of city government in this period, made this aim impossible.[46] In 1834, Ross was asked to compose a list of sites around the Acropolis that were most in need of protection, so that they could be acquired by the state. Working with Pittakis, he identified thirteen, but was initially forced to reduce the list to five, before the proposed initiative was abandoned altogether.[46] In 1835, both to fund the restoration works and to control the number of visitors, the Acropolis became the first archaeological site in the world to charge an entrance fee.[46] Ross's work was seen as part of the broader project of building Athens as the capital of the new Greek state: in 1835, Ross became a member, and subsequently the chair, of the building commission responsible for the planning of the city and of the government's imminent move there from Nafplion.[47] According to an anecdote related by the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen, who visited Ross in Athens in 1841, Ross interceded to prevent the felling of a palm-tree scheduled to be removed to allow the construction of Hermes Street; Andersen therefore dubbed the tree, which remained in the middle of the road, "Ross's Palm".[48]

His role in the planning of Athens's redevelopment occupied Ross throughout 1834, leaving him too little time for archaeological work.[49] His work on the Acropolis began in January 1835,[39] and has been described as the first systematic excavation of the site.[8][lower-alpha 2] Initially, the Acropolis was still occupied by Bavarian soldiers, in defiance of the royal decree of the previous August.[39] Through the support of Egid von Kobell,[lower-alpha 3] a member of Otto's regency council, Ross was able to arrange the soldiers' departure in February[36] and for guards for the archaeological works to be posted in their stead.[52] Klenze set out a series of principles for the restoration, which included the removal of any structures deemed to be of no "archaeological, constructional or picturesque" (German: mahlerisch) interest, reconstruction using fallen parts of the original monuments (anastylosis) as far as possible, and the placement of fragments deemed of aesthetic interest in "picturesque piles" between the monuments.[52]

Since shortly after 1822, Pittakis had been establishing a public collection of the Acropolis's antiquities in the Church of the Megali Panagia, which had become one of Greece's first archaeological museums.[53] Construction work on the church, which began in 1834, necessitated the removal of its collection, by then numbering 618 artefacts, to the Temple of Hephaestus (then known as the Theseion).[54] Klenze's proposals advocated for the removal of some of the Acropolis's remaining fragments of sculpture to be displayed in the Theseion;[52] in March–May 1835, Ross and Schaubert carried out rebuilding and restoration work there to make it suitable for its new role as a museum, which included the demolition of the apse constructed during the monument's use as a Christian church.[55]

On the Acropolis, Ross's initial works of 1835 focused on the Parthenon and on the western approach to the Acropolis, around the Pedestal of Agrippa and what was then known as the Tower of Athena Nike.[36] The so-called "tower" was the former parapet of the Temple of Athena Nike, most of which had been dismantled during the Venetian siege of 1687[56] and whose surviving parapet was serving as a gun emplacement.[57] Ross hired eighty workers, split between the Parthenon and the sites to the west.[58] The first tasks were to demolish the modern bastion near the Tower of Athena Nike and the mosque inside the Parthenon, which Ross justified in his letters to Klenze as necessary to prevent the re-militarisation of the Acropolis,[36] both structures having previously been used by the military garrison.[39] A lack of heavy lifting equipment limited Ross's progress in the Parthenon, making the full demolition of the mosque impossible,[36] but the excavations revealed the first evidence for the Older Parthenon which predated the Periclean temple, as well as fragments and items of statuary from the Classical temple.[58] At some point in 1835, Ross sent casts of part of the Parthenon frieze to Falbe, who had them sent to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen.[59]

At the Tower of Athena Nike, Ross's demolition of the bastion revealed the disiecta membra of the former temple, which has been described by the archaeological historian Fani Mallouchou-Tufano as "one of the greatest moments in the history of the Acropolis in this period".[36] Ross and his collaborators carried out the reconstruction of the temple between December 1835 and May 1836.[36] They arranged the excavated fragments of the temple, as well as other remains of nearby monuments, including the Propylaia, on top of the surviving crepidoma and column bases with little regard for their individual situation.[36] The restoration was hailed at the time as the first full reconstruction of a Classical monument in Greece, but later observers criticised the haste in which the work was undertaken, the incongruity of the use of modern materials where ancient fragments could not be found, and the lack of correspondence between Ross's reconstruction and any plausible original design of the temple.[60]

Throughout his excavations on the Acropolis, Ross published his results in both the academic press and in reports to German newspapers.[61] At a time when relatively few Greek archaeologists worked outside Athens,[62] Ross organised archaeological collections throughout the Cyclades, and conducted excavations on Thera in 1835. On Thera, he unearthed twelve funerary inscriptions, which he divided between Thera, the regional museum on Syros (which he had ordered to be established in 1834–1835)[63] and the Central Museum in Athens.[63] He remained closely connected with the Ottonian court,[10] and guided Otto's father Ludwig I of Bavaria and the German nobleman Hermann von Pückler-Muskau during their respective visits to Greece.[64] He also corresponded closely with the British antiquarian William Martin Leake, who had travelled extensively through Greece in the early 19th century. Leake's final account of his travels, Travels in Northern Greece, was published in 1835 and became the period's standard introduction to the archaeology and topography of Greece.[65]

"Naval Records Affair" and resignation as Ephor General

Ross had a long-running feud with Kyriakos Pittakis,[66] one of the first native Greeks employed by the Greek Archaeological Service.[30] In the first years of the independent Greek state, tensions existed between native Greek archaeologists and the mostly Bavarian scholars who, on the invitation of King Otto, dominated Greek archaeology.[26] In 1834 and 1835, excavations in the harbour of the Piraeus uncovered a series of inscriptions known as the "Naval Records",[63] which gave information on the administration and financing of the Athenian navy between the 5th and 4th centuries BCE.[67] Ross studied the inscriptions and sent sketches to the German scholar August Böckh for the Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, his compilation of ancient Greek inscriptions, despite having not yet received approval to publish them.[63]

The Greek authorities asserted that Ross's actions were illegal: Pittakis attacked Ross in the press,[68] which largely sided against Ross, thanks to Pittakis's service in the War of Independence and xenophobia towards Ross as an ethnic German.[69] Public pressure forced Ross's resignation as Ephor General on 20 September [O.S. 8 September] 1836,[68] though the Education Minister Iakovos Rizos Neroulos unsuccessfully petitioned Armansperg, then prime minister, to refuse it.[69] Eleven days later, Ross attempted to return to the Acropolis to study the inscriptions unearthed during his excavations there, but Pittakis denied him entry.[70]

On Ross's resignation,[71] Pittakis was appointed ephor of the Central Public Museum for Antiquities,[72] making him the most senior archaeologist employed by the Greek Archaeological Service and its de facto head.[73] He received the title of Ephor General in 1843.[71][lower-alpha 4] Until 1838, Pittakis and others continued to write hostile articles against Ross, accusing him of allowing foreign journals privileged access to Greek inscriptions, of improperly giving away antiquities to von Pückler-Muskau during his visit, and of plotting to flee the country with antiquities in his possession.[75] Ross continued to dispute the allegations in the press until April 1838, but made no further response after an article written by Pittakis in May, entitled "Final Answer".[76] The archaeological historian Nikolaos Papazarkadas has argued that Pittakis's opposition to Ross's actions was personal rather than principled, pointing out that Pittakis made no protest against the copying of several thousand Greek inscriptions by French epigraphers from 1843 onwards, a project supported by the prime minister, Ioannis Kolettis.[77]

Professorship at Athens (1837–1843)

The regent Armansperg promised to restore Ross's status as Ephor General, but failed to do so, which cooled relations between himself and Ross.[28] When Otto came of age in 1837, he founded the Othonian University of Athens (known since 1932 as the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens[78]), which was inaugurated on 15 May [O.S. 3 May]. Ross was granted the inaugural professorship of archaeology, one of the first such chairs in the world.[28] Ross's professorship has generally been attributed to Otto's personal favour towards him:[27] it has been suggested that the chair was created specifically for him.[28] Ross was one of 7 Germans out of 23 teaching staff, paid 350 drachmae a month.[79][lower-alpha 5]

Ross's gave the university's first lecture on 22 May [O.S. 10 May], on the topic of Aristophanes, before an audience of around thirty.[82] During his professorship, he lectured widely on Ancient Greek and Latin literature, on the history of Classical Athens and Sparta,[83] and on the topography of Athens, largely basing his course on inscriptions that he had discovered himself.[63] In the 1840–1841 academic year, Ross offered a course in Greek epigraphy, marking the first time that epigraphy had been taught as a distinct discipline in Greece.[63] His students included the future epigrapher and Ephor General Panagiotis Efstratiadis.[84]

Ross was elected as a member of the university's nine-member senate, where he supported the introduction of German-style Privatdozenten, so-called "private lecturers" teaching without the status or rights of full professors.[85] In 1834, he had published the first volume of Inscriptiones Graecae Ineditae ('Unpublished Greek Inscriptions'), a compendium and edition of the Greek inscriptions he had discovered; this was the first epigraphical volume to be published in Greece.[63] He was criticised on its publication for writing in Latin rather than Greek; this criticism may have been part of the reason why he delayed the publication of the second volume, which had been expected in 1835, until 1842.[86] Between May and October 1838, he travelled in Italy, Austria and Germany, staying with the classicist Friedrich Thiersch in Munich and visiting his family in Bornhöved for the first time since his departure for Greece. He spent July in the spa town of Bad Kissingen in Bavaria, where he sought a spa cure for an illness.[87] In 1839, he published the results of his excavations at the Temple of Athena Nike, in a volume illustrated by Hansen and Schaubert.[88]

In 1841, Ross published his Handbook of the Archaeology of the Arts, written in katharevousa Greek.[89] The Greek archaeologist Olga Palagia has described the Handbook as both "a model of the scientific method for its time" and "a monument to the Greek language".[83] In the volume, Ross promoted neoclassicist ideals, by which he argued that art and architecture should adapt and imitate the models of classical antiquity, placing comparatively little emphasis on historical questions about the development of Greek architecture.[90] Ross also argued for the dependence of Ancient Greek culture on that of Egypt and the ancient Near East,[83] which contrasted with the then-fashionable view of Classical "purity" advanced by Johann Joachim Winckelmann and his successors, such as Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy and Karl Bötticher.[91]

During his tenure at Athens, Ross travelled widely throughout Greece, including a journey to Marathon in 1837 with his brother Charles and Ernst Curtius, the future excavator of Olympia.[92] Alongside archaeology, he took an interest in modern Greek ethnography and folklore, including the spread of the Greek language,[93] which he spoke sufficiently fluently that Greeks often mistook him for a native.[94] In August and September 1837, he travelled through the Greek islands, visiting Sikinos, Sifnos, Amorgos, Kea, Kythnos, Santorini and Ios, accompanied by the German geographer Carl Ritter and the Scottish historian George Finlay.[95] Ross published his explorations on Sikinos as The Archaeology of the Island of Sikinos.[96] His archaeological description of Sifnos was described by the American archaeologist John H. Young in 1956 as "still the best account of the island we possess ... for more than a hundred years of archaeological research has still produced no better guide to the islands than Ross".[97]

Ross subsequently travelled through the Greek islands and Asia Minor, making him one of the first Europeans to explore the interior of Caria and Lycia,[98] in 1841 and 1843. He published an account of his travels as Journeys on the Greek Islands of the Aegean Sea in 1843 and 1845.[99] He took leave of absence for about half of 1839 and all of 1842, during which he visited Germany and Italy, and did not teach at all during the academic year 1841–1842.[100] He regularly accompanied King Otto on archaeological travels during his time at Athens,[28] including a tour of the Peloponnese with Queen Amelie in May–June 1840, which Ross considered one of his most successful journeys.[101] He was appointed to the Prussian Academy of Sciences in 1836,[102] and as a corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences in 1837.[103]

By the late 1830s, negative comments in the Greek press about the so–called "Bavarocracy"[lower-alpha 6] had become common, and the dominance of northern Europeans in Greek academia, archaeology and architecture had become a source of considerable unrest.[104] The appointment of Alexandros Mavrokordatos, who opposed the presence of foreigners in Greek public life, as Prime Minister in 1841 caused Ross concern, and he entered a severe depression during this period which continued for the remainder of his life.[105] By 1842, he was dissatisfied with his lectures at the University, frustrated by the continued hostility of Pittakis and his supporters, and keen to leave Greece.[106] He unsuccessfully applied for an academic post in Dresden and for a travel grant from the Danish government to travel in southern Europe. In March, he resigned from his post at the University of Athens, intending to stay in Greece for a few months before moving to Germany.[107] He also wrote to Moritz Hermann Eduard Meier at the University of Halle in the German state of Saxony, then ruled by Prussia,[10] asking for a post there.[108]

During his Aegean travels of 1843, Ross received news of the military coup that had taken place on 15 September [O.S. 3 September] of that year and had forced Otto to dismiss almost all of the non-Greeks in public service.[109] Ross was succeeded as Professor of Archaeology at Athens by the Constantinople-born Greek archaeologist and polymath Alexandros Rizos Rangavis in 1844.[110]

Professorship at Halle (1843–1859)

Through the support of his friend, the German polymath Alexander von Humboldt, Ross was appointed to the professorship of archaeology at Halle shortly after the 1843 revolt. The beginning of his employment was delayed by King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, who granted him a two-year travel stipendium,[10] allowing him to spend time in Smyrna, Trieste and Vienna.[111] During the winter of 1844–1845, he organised excavations, led by Eduard Schaubert, near Olympia.[8] The project was financed by the Prussian Ministry of Culture and Friedrich Wilhelm, to whom Humboldt had recommended it.[112] Schaubert's excavations investigated a site reputed to be the grave of Coroebus of Elis, the supposed victor of the first Olympic Games in 776 BCE, hoping to assess the origins of the Olympic Games and the historicity of Coroebus.[8] The excavations were concluded in 1846,[113] having found the remains of a grave of uncertain date, with traces of ashes, animal bones and pottery sherds, as well as bronze vessels and a bronze helmet, which Schaubert interpreted as remains of a hero cult on the site.[114]

A man named "L. Ross" was referenced by the Arabist Otto Blau as visiting the archaeological site of Petra, Jordan, in 1845.[115] Blau describes "Ross" as an Englishman, but the archaeologist David Kennedy has argued that Blau may have mistaken the nationality of the Scottish-descended Ludwig Ross, which would make Ross one of the earliest scholars to visit the site.[116]

Ross eventually took up his professorship at Halle in 1845.[10] He was an isolated figure in German academia, partly due to his criticism of well-respected scholars like the philologist Friedrich August Wolf and the historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr. His then-unfashionable emphasis upon the links between Greek and Near Eastern civilisation placed him in conflict with the views of the prominent classicist Karl Otfried Müller, who had argued for the autochthonous nature of Ancient Greek culture.[117] Ross's views were supported by the historian Julius Braun in Germany and by the archaeologist Desiré-Raoul Rochette in Paris.[118] During a debate at Halle over the layout of its museum of art, Ross proposed that exhibits should be displayed on four walls, giving equal prominence to objects from Greece, Rome, Egypt and Asia.[119]

He published the third volume of Inscriptiones Graecae Ineditae in 1845, and a treatise on the demes of Attica with his colleague Eduard Meier in 1846.[120] In 1848, he published Italics and Greeks: Did the Romans Speak Sanskrit or Greek?, in which he argued that Latin was a linguistic descendant of Greek in the same way that the Romance languages are descended from Latin,[121] rejecting the emerging discoveries in the field of Indo-European studies. In 1850, he co-founded a monthly literary journal, the Allgemeine Monatsschrift für Literatur, with the historian Johann Gustav Droysen and the publisher Carl Gustav Schwetschke, Ross's father-in-law. The journal ceased publication after only a few years.[122]

Ross intended to publish his excavations of the Parthenon and the area of the Propylaia, complementing his 1839 publication of the Temple of Athena Nike, but had been forced by 1855 to abandon the project, partly due to financial constraints and partly due to the difficulty of collaborating with his co-authors Hansen and Schaubert without being physically present in Greece.[123] Both Müller (in 1843) and the French archaeologist Philippe Le Bas (in 1847) had already published some of the discoveries from the Temple of Athena Nike, relying on drawings made by others.[124]

Personal life, death and legacy

Early in 1847, Ross married Emma Schwetschke, the daughter of his future collaborator Carl Gustav Schwetschke.[120] Shortly thereafter, he developed the beginnings of a health condition, which gradually reduced his strength and mobility and caused him increasing pain and discomfort.[118] He attempted, unsuccessfully, to treat his condition with spa cures.[118] He may have suffered from syphilis, evidence of which the archaeological historian Ida Haugsted has traced to Ross's letters of early 1842.[106] He continued to suffer from the depression which had begun to affect him in the later years of his time in Greece.[105]

Ross died by suicide[10] in Halle on 6 August 1859.[125] He was buried in Bornhöved,[126] alongside his brother, Charles, who had died of typhus the previous year.[127]

Ross's reflections on his career in Greece, Reminiscences and Communications from Greece, were published posthumously in 1863, with a foreword by his friend Otto Jahn.[128] In the volume, which consisted largely of Ross's diaries and letters from his time in Greece, Ross alleged that technological backwardness and governmental incompetence had held back the development of Greece, and criticised both Otto's government and native Greek politicians for their "localism" and the alleged weakness and lethargy of the royal administration.[129]

Ross has been praised as one of the greatest figures in Greek epigraphy and as an important force in its beginnings as an academic discipline.[77] Haugsted has described him as "one of the most important figures in the cultural revival of Greece."[1] Ross's work was used heavily by August Böckh in his own influential epigraphical works, a debt which Böckh acknowledged in the subtitle of his 1840 work Documents on the Maritime Affairs of the Athenian State: "with eighteen panels, containing the copies made by Mr. Ludwig Ross."[130] Though the execution of his restoration of the Temple of Athena Nike has been criticised,[60] his excavation and restoration work has been praised for its systematic approach and for beginning a long trend of similar endeavours on the Acropolis.[8] He has generally been viewed as a competent and successful Ephor General,[131] whose service and resignation had considerable consequences for the development of Greek archaeology.[132]

Footnotes

Notes

- ↑ Until 1923, Greece used the Julian Calendar, known as the Old Style.[19]

- ↑ Earlier removals of archaeological material from the Acropolis and other ancient sites included the taking of most of the sculptures from the Parthenon by the British aristocrat Lord Elgin in the early nineteenth century, and other opportunistic removals in the aftermath of the Greek War of Independence. These have been described as "looting" and "vandalism".[50]

- ↑ Quoting the relevant passage from Ross's memoirs, Mallouchou-Tufano gives the name as "Mr. von Kombell", and names him as a member of the regency.[36] At the time, the members of the regency council were Kobell, Armansperg and Carl Wilhelm von Heideck,[51] making Kobell the only plausible intended name.

- ↑ According to Kokkou, Pittakis was not formally named to the position until 12 January 1849 [O.S. 31 December 1848].[74]

- ↑ The archaeological historian Yannis Galanakis describes this as a "relatively small salary" for the period.[80]

- ↑ In Greek, called the Βαυαροκρατία (Bavarokratia).

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Haugsted 1996, p. 79.

- 1 2 Dyson 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ The Spectator Supplement 1863, p. 19.

- ↑ Jahn 1863, p. vii.

- ↑ Minner 2006, p. 32.

- ↑ Minner 2006, p. 30.

- ↑ Von Donop 1889, p. 245.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lehmann 2021, p. 184.

- 1 2 3 Lund 2019, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Brandl 1987, p. 118.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Baumeister 1889, p. 247.

- 1 2 3 Minner 2006, p. 52.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 81.

- ↑ Palagia 2005, p. 294; Sorensen 2022.

- 1 2 Minner 2006, p. 68.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 79. For average wages in Denmark during this period, see Khaustova & Sharp 2015, p. 6.

- 1 2 Haugsted 1996, p. 80.

- ↑ Helm 2000, p. 6.

- ↑ Kiminas 2009, p. 23.

- ↑ Stevenson 1993, p. 705; Tikkanen 2022.

- ↑ Helm 2000, p. 8.

- ↑ Petrakos 2004, p. 122.

- ↑ Petrakos 2011, p. 136. Petrakos gives the title in Greek, as ἐπιστάτης τῶν ἐν Ἀθήναις ἀρχαιοτήτων (epistatis ton en Athinais archaiotiton).

- ↑ Petrakos 2004, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, pp. 83–84.

- 1 2 3 Voutsaki 2003, p. 245.

- 1 2 Junker 1995, p. 755.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Palagia 2005, p. 267.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 89; Petrakos 2011, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 Petrakos 2011, p. 57.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 90.

- 1 2 Lehmann 2003, p. 167.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 238.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 92.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mallouchou-Tufano 2007, p. 41.

- ↑ Mallouchou-Tufano 2007, p. 38.

- ↑ Petrakos 1998, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mallouchou-Tufano 2007, p. 40.

- ↑ Stillwell 1960, p. 93. In Greek, the title was Γενικὸς Ἔφορος τῶν Ἀρχαιοτῆτων (Genikos Eforos ton Archaiotiton).

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 115. For average wages during this period, see Katsikas 2022, p. 126.

- ↑ Petrakos 2011, p. 136.

- ↑ Kubala 2019, p. 258.

- ↑ Casanaki & Mallouchou 1985, p. 14.

- ↑ Dyer 1873, p. 373.

- 1 2 3 Costaki 2021, p. 463.

- ↑ Helm 2000, p. 9; Haugsted 1996, p. 115.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 236.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 121.

- ↑ Fagan & Durrani 2015, p. 385; Kitromilides 2021.

- ↑ Lund 2019, p. 13; Frazee 1969, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 Jokilehto 2007, p. 93.

- ↑ Kokkou 2009, p. 158.

- ↑ Kokkou 2009, p. 160; Tsouli 2020, p. 269.

- ↑ Mallouchou-Tufano 2016, p. 196.

- ↑ Giraud 2018, p. 32.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1995, p. 238.

- 1 2 Mallouchou-Tufano 1994, p. 71.

- ↑ Lund 2019, p. 25.

- 1 2 Mallouchou-Tufano 1994, p. 72.

- ↑ Petrakos 2011, p. 58.

- ↑ Antoniadis & Kouremenos 2021, p. 188.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Papazarkadas 2014, p. 403.

- ↑ Baumeister 1889, p. 248.

- ↑ Petrakos 2007, p. 20.

- ↑ Athanassoglou-Kallmyer 2008, p. 12.

- ↑ Gabrielsen 2014, pp. 39–40.

- 1 2 Papazarkadas 2014, p. 404; Maniatea 2022.

- 1 2 Petrakos 2013, p. 103.

- ↑ Maniatea 2022.

- 1 2 Petrakos 2011, p. 59.

- ↑ Tsouli 2020, p. 268.

- ↑ Petrakos 2011, p. 134.

- ↑ Kokkou 2009, p. 89.

- ↑ Kokkou 2009, p. 82.

- ↑ Kokkou 2009, p. 82. In Greek, the title of Pittakis's article was Τελευταία Άπάντησις (Teleftaia Apantisis).

- 1 2 Papazarkadas 2014, p. 404.

- ↑ National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Department of Chemistry 2020.

- ↑ Palagia 2005, p. 270.

- ↑ Galanakis 2012.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 223.

- ↑ Palagia 2005, p. 269. Ross reported the date as 22 May [O.S. 10 May] in a letter; Haugsted gives it as 27 June [O.S. 15 June].[81]

- 1 2 3 Palagia 2005, p. 271.

- ↑ Petrakos 2011, p. 15.

- ↑ Palagia 2005, p. 270. Palagia uses the Greek title υφηγηταί (yphigitai).

- ↑ Papazarkadas 2014, p. 410.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 213.

- ↑ Junker 1995, pp. 755–756.

- ↑ Palagia 2005, p. 271. In Greek, the title was Εγχειρίδιον της Αρχαιολογίας των Τεχνών (Encheiridion tis Archaiologias ton Technon).

- ↑ Fatsea 2017, pp. 65–68.

- ↑ Fatsea 2017, p. 68.

- ↑ Goette 2015, p. 219.

- ↑ Helm 2000, p. 14.

- ↑ Helm 2000, p. 9.

- ↑ Arnott 1990, p. 2; Palagia 2005, p. 275.

- ↑ Palagia 2005, p. 275. In Greek, the book's title was Η Αρχαιολογία της Νήσου Σικίνου (I Archaiologia tis Nisou Sikinou).

- ↑ Young 1956, p. 51.

- ↑ Marek & Frei 2016, p. 22.

- ↑ Palagia 2005, p. 276. The work was published in German, under the title Reisen auf den griechischen Inseln des Ägäischen Meeres.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 289; Palagia 2005, p. 270.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 234.

- ↑ Bavarian Academy of Sciences 2022.

- ↑ Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences 2015.

- ↑ Bastea 1997, p. 57.

- 1 2 Haugsted 1996, pp. 235–236.

- 1 2 Haugsted 1996, p. 241.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 289.

- ↑ Haugsted 1996, p. 291.

- ↑ Petrakos 2011, p. 58; Palagia 2005, p. 276; Frary 2015, p. 204; Reid 2000, p. 248.

- ↑ Petrakos 2011, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Minner 2006, p. 266.

- ↑ Minner 2006, p. 359.

- ↑ Lehmann 2003, p. 165.

- ↑ Lehmann 2003, p. 166.

- ↑ Blau 1855, p. 232.

- ↑ Kennedy 2015.

- ↑ Brandl 1987, p. 118; Baumeister 1889, p. 250.

- 1 2 3 Baumeister 1889, p. 251.

- ↑ Helm 2000, pp. 18–20.

- 1 2 Baumeister 1889, p. 250.

- ↑ Baumeister 1889, p. 252. The work was published in German, under the title Italiker und Gräken. Sprachen die Römer Sanskrit oder Griechisch?.

- ↑ Sorensen 2022.

- ↑ Junker 1995, p. 756.

- ↑ Junker 1995, p. 761.

- ↑ Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Berlin 1859, p. vii.

- ↑ Baumeister 1889, p. 252.

- ↑ Von Donop 1889, p. 246.

- ↑ Ross 1863. The book was published in German under the title Erinnerungen und Mittheilungen aus Griechenland.

- ↑ The Spectator Supplement 1863, p. 20.

- ↑ Papazarkadas 2014, p. 410. The work was published in German, under the title Urkunden über das Seewesen des Attischen Staates.

- ↑ Fatsea 2017, p. 65; Papazarkadas 2014, p. 404.

- ↑ Petrakos 2007, p. 20; Papazarkadas 2014, p. 404.

Bibliography

- Antoniadis, Vyron; Kouremenos, Anna (2021). "Selective Memory and the Legacy of Archaeological Figures in Contemporary Athens: The Case of Heinrich Schliemann and Panagiotis Stamatakis". The Historical Review/La Revue Historique. 17: 181–204. doi:10.12681/hr.27071. S2CID 238067293.

- Arnott, Robert (1990). "Early Cycladic Objects from Ios Formerly in the Finlay Collection". Annual of the British School at Athens. 85: 1–14. doi:10.1017/S0068245400015525. JSTOR 30102836. S2CID 161679601.

- Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Nina (2008). "Excavating Greece: Classicism between Empire and Nation in Nineteenth-Century Europe". Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. 7 (2). Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Bastea, Eleni (1997). "Nineteenth-Century Travellers in the Greek Lands: Politics, Prejudice, and Poetry in Arcadia" (PDF). Dialogos: Hellenic Studies Review, UK (4): 47–69. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Baumeister, August (1889), "Ludwig Roß", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 29, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 246–253

- Bavarian Academy of Sciences, ed. (2022). "Prof. Dr. Ludwig Roß". Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, ed. (7 June 2015). "Ludwig Ross". Mitglieder der Vorgängerakademien (in German). Archived from the original on 27 December 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Blau, Otto (1855). "Inschriften aus Petra" [Inscriptions from Petra]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (in German). 9 (1): 230–237, 308. JSTOR 43364860.

- Brandl, Rudolf M. (1987). "Griechische Volksmusik im 19. Jahrhundert: Beobachtungen in Reisebeschreibungen von Göttinger Gelehrten" [Greek Folk Music in the 19th Century: Observations in Travelogues by Gottingen Scholars]. In Staehelin, Martin (ed.). Musikwissenschaft und Musikpflege an der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen: Beiträge zu ihrer Geschichte (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-35832-0.

- Casanaki, Maria; Mallouchou, Fani (1985). "Interventions on the Acropolis: 1833–1975". The Acropolis at Athens: Conservation, Restoration and Research 1975–1983. Athens: ESMA. pp. 12–20. OCLC 13537815.

- Costaki, Leda (2021). "Urban Archaeology: Uncovering the Ancient City". In Neils, Jenifer; Rogers, Dylan K. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 462–481. doi:10.1017/9781108614054. ISBN 978-1-108-61405-4. S2CID 243691800.

- von Donop, Lionel (1889), "Roß, Ludwig", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 29, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 243–246

- Dyer, Thomas Henry (1873). Ancient Athens: Its History, Topography, and Remains. London: Bell and Daldy. OCLC 910991294. Retrieved 23 December 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Dyson, Stephen L. (2008). In Pursuit of Ancient Pasts: A History of Classical Archaeology in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13497-1.

- Fagan, Brian; Durrani, Nadia (2015). In the Beginning: An Introduction to Archaeology (13th ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-34643-2.

- Fatsea, Irene (2017). "The Reception of J.J. Wincklemann During the Formative Years of the Modern Greek State (1832–1862)". In Cartledge, Paul; Voutsaki, Sofia (eds.). Ancient Monuments and Modern Identities: A Critical History of Archaeology in 19th and 20th Century Greece. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 62–76. ISBN 978-1-315-51344-7.

- Frary, Lucien J. (2015). Russia and the Making of Modern Greek Identity, 1821–1844. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-873377-5.

- Frazee, Charles A. (1969). The Orthodox Church and Independent Greece, 1821–1852. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-07247-2.

- Gabrielsen, Vincent (2014). "The Piraeus and the Athenian Navy: Recent Archaeological and Historical Advances". Proceedings of the Danish Institute at Athens. 4: 37–48. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Galanakis, Yannis (30 November 2012). "On Her Majesty's Service: C.L.W. Merlin and the Sourcing of Greek Antiquities for the British Museum". Center for Hellenic Studies Research Bulletin. Harvard University. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- Giraud, Demosthenes (2018). "War as a Cause of Genesis and Obliteration of Monuments (The Case of the Athenian Acropolis)". In Kouis, Dimitrios; Zezza, Fulvio; Koui, Maria (eds.). 10th International Symposium on the Conservation of Monuments in the Mediterranean Basin: Natural and Anthropogenic Hazards and Sustainable Preservation. New York: Springer. pp. 29–60. ISBN 978-3-319-78093-1.

- Goette, Hans Rupprecht (2015). "Ludwig Ross in Attica und auf Aegina" [Ludwig Ross in Attica and on Aegina]. In Goette, Hans Rupprecht; Palagia, Olga (eds.). Ludwig Ross und Griechenland: Acten des Internationalen Kolloquiums, Athen, 2–3. Oktober 2002 (in German). Rahden: Marie Leidorf. pp. 219–232. ISBN 978-3-89646-424-8.

- "Greece and the Greeks". The Spectator Supplement. London. 27 March 1863. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- Haugsted, Ida (1996). Dream and Reality: Danish Antiquaries, Architects and Artists in Greece. London: Archetype Publications. ISBN 978-1-873132-75-3.

- Helm, Christoph (2000). "Ludwig Ross und seine Bedeutung für die klassischen Altertumswissenschaften" [Ludwig Ross and His Importance for Classical Ancient History]. In Kunze, Max (ed.). Akzidenzen 12: Flugblätter der Winckelmann-Gesellschaft [Accidents 12: Pamphlets of the Winckelmann Society] (PDF) (in German). Stendal: Winckelmann-Gesellschaft. pp. 3–24. OCLC 1249640687. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 24 December 2022..

- "Historische Einleitung" [Historical Introduction]. Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Berlin (in German): i–vii. 1859. Retrieved 27 April 2023 – via Google Books.

- Jahn, Otto (1863). "Vorwort" [Foreword]. Erinnerungen und Mittheilungen aus Griechenland [Reminiscences and Communications from Greece]. By Ross, Ludwig (in German). Berlin: Verlag von Rudolf Gaertner. pp. i–xxx. OCLC 679973174.

- Jokilehto, Jukka (2007) [1999]. History of Architectural Conservation. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-39850-6.

- Junker, Klaus (1995). "Ludwig Ross und die Publikation seiner Ausgrabungen auf der Athener Akropolis" [Ludwig Ross and the Publication of His Excavations on the Athenian Acropolis]. Archäologischer Anzeiger (in German): 755–762.

- Katsikas, Stephanos (2022). Proselytes of a New Nation: Muslim Conversions to Orthodox Christianity in Modern Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-762175-2.

- Kennedy, David (11 January 2015). "'L. Ross' at Petra in 1854". East of Jordan. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- Khaustova, Ekaterina; Sharp, Paul (2015). A Note on Danish Living Standards through Historical Wage Series, 1731–1913. The Journal of European Economic History. Vol. 44. pp. 143–172. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- Kiminas, Demetrius (2009). The Ecumenical Patriarchate. San Bernardino: The Borgo Press. ISBN 978-1-4344-5876-6.

- Kitromilides, Paschalis M. (2021). "Introduction: In an Age of Revolution". In Kitromilides, Paschalis M.; Tsoukalas, Konstantinos (eds.). The Greek Revolution: A Critical Dictionary. Translated by Douma, Alexandra. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-0-674-98743-2.

- Kokkou, Angeliki (2009) [1977]. Η μέριμνα για τις αρχαιότητες στην Ελλάδα και η δημιουργία των πρώτων μουσείων [The Attitude Towards Antiquities in Greece and the Founding of the First Museums] (in Greek). Athens: Kapon Editions. ISBN 978-960-6878-11-4.

- Kubala, Agata (2019). "Philhellenic Attitudes: Eduard Schaubert's Wrocław Collection: An Account of Its Antiquities and the Circumstances of Its Formation". Journal of the History of Collection. 31 (2): 257–269. doi:10.1093/jhc/fhy019.

- Lehmann, Stephan (2003). "Olympia, das Grab des Koroibos und die Altertumswissenschaften in Halle" [Olympia, the Tomb of Koroibos and Ancient History in Halle]. In Bertke, Ellen; Kuhn, Heike; Lennartz, Karl (eds.). Olympisch bewegt: Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag von Prof. Dr. Mannfred Lämmer (in German). Cologne: Die Deutsche Bibliotek. pp. 163–176. ISBN 3-88338-006-7.

- Lehmann, Stephan (2021). "Zu den Anfängen der Klassischen und „vaterländischen" Altertumskunde" [On the Beginnings of Classical and "Fatherland" Antiquity]. In Wiwjorra, Ingo; Hakelberg, Dietrich (eds.). Archäologie und Nation: Kontexte der Erforschung "vaterländischen Alterthums": Zur Geschichte der Archäologie in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz, 1800 bis 1860 (in German). Heidelberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum. pp. 174–187. doi:10.11588/arthistoricum.801.c11981. ISBN 978-3-948466-84-8. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- Lund, John (2019). "Christian Tuxen Falbe: Danish Consul-General and Antiquarian in Greece, 1833–5". Proceedings of the Danish Institute at Athens. 9: 11–34. doi:10.2307/j.ctv34wmvm0.4.

- Mallouchou-Tufano, Fani (1994). "The History of Interventions on the Acropolis". In Economakis, Richard (ed.). Acropolis Restoration: The CCAM Interventions. Athens: Academy Editions. pp. 69–85. ISBN 978-1-85490-344-0.

- Mallouchou-Tufano, Fani (2007). "The Vicissitudes of the Athenian Acropolis in the Nineteenth Century: From Castle to Monument". In Valavanis, Panos (ed.). Great Moments in Greek Archaeology. Athens: Kapon Press. pp. 36–57. ISBN 978-0-89236-910-2.

- Mallouchou-Tufano, Fani (2016). Οι τύχες ενός κλασικού ναού στην νεώτερη Ελλάδα: Η πρόταση για την 'ολοσχερή' αναστήλωση του 'Θησείου' και άλλα επεισόδια [The Fortunes of a Classical Temple in Modern Greece: The Proposal for the 'Complete' Restoration of the 'Theseion' and Other Episodes]. Αρχιτέκτων: τιμητικός τόμος για τον καθηγητή Μανόλη Κορρέ (in Greek). Athens: Εκδοτικός Οίκος Μέλισσα [Ekdotikos Oikos Melissa]. pp. 195–204. ISBN 978-960-204-353-0.

- Maniatea, Tonia (19 November 2022). Ειδικο Θεμα: Κυριακός Πιττάκης, ο πρώτος αυτοδίδακτος Έλληνας αρχαιολόγος [Special Topic: Kyriakos Pittakis, the First Self-Taught Greek Archaeologist] (in Greek). Athens-Macedonian News Agency. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- Marek, Christian; Frei, Peter (2016). In the Land of a Thousand Gods: A History of Asia Minor in the Ancient World. Translated by Rendall, Steven. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18290-2.

- Minner, Ina E. (2006). Ewig ein Fremder im fremden Lande – Ludwig Ross (1806–1859) und Griechenland. Biographie [Forever a Foreigner in a Foreign Land – Ludwig Ross (1806–1859) and Greece] (in German). Möhnesee-Wamel: Bibliopolis. ISBN 3-933925-82-7.

- National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Department of Chemistry (2020). "Short History of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens". Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- Palagia, Olga (2005). Λουδοβίκος Ροσς, πρώτος καθηγητής αρχαιολογίας του Πανεπιστημίου Αθηνών [Ludwig Ross, First Professor of Archaeology at the University of Athens]. In Goette, Hans R.; Palagia, Olga (eds.). Ludwig Ross und Griechenland : Akten des internationalen Kolloquiums, Athen, 2.-3. Oktober 2002 (in Greek). Rahden: Marie Leidorf. pp. 267–276. ISBN 978-3-89646-424-8.

- Papazarkadas, Nikolaos (2014). "Epigraphy in Early Modern Greece". Journal of the History of Collections. 26 (3): 399–412. doi:10.1093/jhc/fhu018.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (1998). Η ελληνική αντίληψη για τα μνημεία από τον Κυριακό Σ. Πιττάκη έως σήμερα [The Greek Perception of Monuments from Kyriakos S. Pittakis to Today]. Mentor. 47: 65–112.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (2004). Η απαρχή της ελληνικής αρχαιολογίας και η ίδρυση της Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας [The Beginning of Greek Archaeology and the Foundation of the Archaeological Society] (PDF). Mentor. 73: 111–220. ISSN 1105-1205. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (2007). "The Stages of Greek Archaeology". In Valavanis, Panos (ed.). Great Moments in Greek Archaeology. Athens: Kapon Press. pp. 16–35. ISBN 978-0-89236-910-2.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (2011). Η Εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογική Εταιρεία: οι αρχαιολόγοι και οι ανασκαφές 1837–2011 (κατάλογος εκθέσεως) [The Archaeological Society of Athens: The Archaeologists and the Excavations 1837–2011 (Exhibition Catalogue)]. Athens: Archaeological Society of Athens. ISBN 978-960-8145-86-3.

- Petrakos, Vasileios (2013). Πρόχειρον αρχαιολογικόν 1828–2012: Μέρος Ι: Χρονογραφικό [Archaeological Handbook 1828–2012: Part 1: Chronological] (PDF) (in Greek). Athens: Archaeological Society of Athens. ISBN 978-618-5047-00-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- Reid, James J. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839–1878. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-07687-6.

- Ross, Ludwig (1863). Erinnerungen und Mittheilungen aus Griechenland [Reminiscences and Communications from Greece] (in German). Berlin: Verlag von Rudolf Gaertner. OCLC 679973174.

- Sorensen, Lee (2022). "Ludwig Ross". Dictionary of Art Historians. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- Stevenson, Christine (1993). "Reviewed Work(s): Sketches and Measurings: Danish Architects in Greece 1818–1862 by Margit Bendtsen and Séan Martin". The Burlington Magazine. 135 (1087): 705–706. JSTOR 885750.

- Stillwell, Richard (1960). "The Parthenon in 1834". Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University. 19 (1): 93–97. doi:10.2307/3774369. JSTOR 3774369.

- Tikkanen, Amy (22 July 2022). "Otto". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 26 December 2022.

- Tomlinson, R.A. (1995). "The Sanctuary of Athena Nike in Athens: Architectural Stages and Chronology by I. S. Mark". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 115: 238. doi:10.2307/631722. JSTOR 631722. S2CID 162708992.

- Tsouli, Chrysanthi (2020). "Kyriakos Pittakis: Sincere Patriot, Unwearied Guard and Vigilant Εphor of Αntiquities". In Lagogianni-Georgakarakos, Maria; Koutsogiannis, Thodoris (eds.). These Are What We Fought For: Antiquities and the Greek War of Independence. Athens: Archaeological Resources Fund. pp. 266–275. ISBN 978-960-386-441-7.

- Voutsaki, Sofia (2003). "Archaeology and the Construction of the Past in Nineteenth Century Greece". In Hokwerda, Hero (ed.). Constructions of the Greek Past: Identity and Historical Consciousness from Antiquity to the Present. Groningen: Egbert Forsten. pp. 231–255. ISBN 978-90-04-49546-3.

- Young, John H. (1956). "Ancient Towers on the Island of Siphnos". American Journal of Archaeology. 60 (1): 51–55. doi:10.2307/500088. JSTOR 500088. S2CID 191393289.

External links

- Literature by and about Ludwig Ross in the German National Library catalogue