Luis Arellano Dihinx | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Luis Arellano Dihinx 1906 |

| Died | 1969 (aged 62–63) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | lawyer |

| Known for | Politician |

| Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista, FET |

Luis Arellano Dihinx (1906–1969) was a Spanish Carlist and Francoist politician. He is recognized as one of the leaders of the so-called Juanistas, a faction within Carlism pressing recognition of the Alfonsist claimant Don Juan de Borbón as a legitimate Carlist heir to the throne.

Family and youth

The Arellano family counts among the oldest ones in Navarre; it was first noted in the 14th century and is related to the family of medieval Navarrese kings.[1] Over the centuries it got extremely branched with representatives in many regions of Spain, though mostly in the North.[2] One of its branches held large estates in Caparroso, in the Southern part of Navarre known as Ribera Aragón; in the early 19th century José Arellano y Ochoa was its alcalde and one of key figures.[3] Luis's father, Cornelio Arellano Lapuerta (1867-1935), a native of Caparroso, made his name as engineer and entrepreneur, growing into mid-ranks of the Navarrese bourgeoisie. His engineering works ranged from Irati Train, the railroad line connecting Pamplona and Sangüesa across a difficult, wooded and hilly Irati terrain,[4] to hydrotechnical constructions on the Ebro and other rivers.[5] He held stakes in Hidráulica de Moncayo[6] and was long-time vice-president of Arteta, a water-pipe company.[7] He is best known, however, as co-founder and co-owner of Múgica, Arellano y Compañía, the Pamplona-based company which produced and traded agricultural machinery.[8] Already in the 1920s it operated 20 subsidiaries, some of them as far as Badajoz, Seville and Cordoba;[9] later on it grew to the 16-th largest company in Navarre.[10] In the 1930s Cornelio Arellano was among the most influential people in the Navarrese power-generation industry[11] and a well recognized engineer.[12]

Cornelio Arellano married a Pamplonesa, Juana Dihinx Vergara (1872-1969);[13] with her father, Pascual Dihinx Azcárate, also an engineer engaged in Hidraúlica de Moncayo and other companies, she was coming from the same bourgeoisie background.[14] The newlyweds followed the professional lot of Cornelio; in the early 20th century they lived in Zaragoza,[15] to settle in Madrid in the 1920s.[16] The couple had 7 children, 5 of them boys.[17] Political preferences of Cornelio and Juana are not clear, except that she came from the family cultivating the Basque heritage; however, they brought up the children in highly Catholic ambience. It is not known whether Luis frequented the schools in Madrid or elsewhere, though he enrolled at the Jesuit University of Deusto in Bilbao. He graduated in law and economics at unspecified time in the late 1920s.[18] In February 1936[19] he married María Dolores Aburto Renobales (?-2004), descendant to a wealthy bourgeoisie Biscay family. Her father, Eduardo Aburto Uribe, was engineer involved in number of provincial industrial enterprises, shareholder of many Biscay mining and metalworking companies, and alcalde of Getxo between 1916 and 1920.[20] Luis and María had 4 sons;[21] active in business, they did not engage in politics. Many of Luis' siblings were active in Traditionalism. Two of his younger brothers were executed by Republican militia in the Bilbao Angeles Custodios prison;[22] an older one was later to become a Jesuit priest and another one a construction engineer.[23] His sister María Teresa worked as a Carlist nurse during the Civil War.[24]

Republic

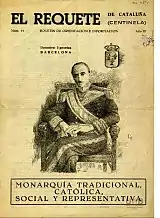

Given lack of information on political preferences of his parents it is not clear whether Arellano inherited the Carlist outlook from his ancestors; it appears to be the case as most of the siblings got involved in Traditionalism. It is also neither known whether he was engaged in any of the three Traditionalist streams prior to their re-unification in the early 1930s. He is probably first noted as active within the public realm during the first electoral campaign of the Republic in 1931; engaged in Juventud Tradicionalista,[25] he kept delivering harangues in favor of Carlist candidates in small locations like Sangüesa in Eastern Navarre.[26] Already the following year he was recorded busy in Carlist propaganda beyond his native region, speaking at various meetings during Gran Setmana Tradicionalista in Catalonia.[27] During that period he must have approached Tomás Domínguez Arévalo, the Carlist national political leader, 24 years his senior but native of Villafranca, just 9 km away from Caparroso. When discussing the 1933 events scholars already refer to Arellano as Arévalo's protégé;[28] indeed conde Rodezno remained Arellano's mentor for the next 20 years.

During the 1933 electoral campaign, Arellano was included as Carlist candidate on the Navarrese Union of the Right coalition;[29] he was comfortably elected with 72 thousand votes and together with José Luis Zamanillo became one of the youngest Traditionalist deputies ever.[30] In great national politics Arellano followed Rodezno and his policy of seeking alliance within a broad monarchist grouping, first in coalition named as TYRE[31] and later having signed manifiesto constitutivo of Bloque Nacional;[32] he remained active in the latter despite discouragement from the emerging Carlist leader, Manuel Fal Conde.[33] Another thread of his activity was a penchant for social focus. In the early 1930s Arellano was already engaged in rural arbitration bodies like Jurado Mixto del Trabajo Rural[34] and Catholic-sponsored labor organizations like Federación Católico-Social Navarra[35] and Sindicatos Obreros Profesionales.[36] Partially as representative of these organizations he entered Grupo Social Parliamentario.[37] Finally, in the Cortes he was very active fighting comisión gestora and demanding re-establishment of Diputación Foral de Navarra.[38]

Following deposition of Rodezno Arellano continued as a rising star in the movement; despite his status of Rodezno's companion, he remained on good terms with the Carlist leader Fal Conde.[39] As part of re-modeling of the party command structures, in 1934 Arellano was appointed jefe of the newly created Youth Section;[40] initially he controlled Juventud Tradicionalista, student AET and paramilitary Requeté organizations, though there was another separate section soon created for the militia later on.[41] At that time he seemed a bit of a pivotal figure, in-between possibilist Rodezno's strategy and the intransigence of Fal. He continued within Bloque Nacional until Fal ordered termination of the alliance. By some scholars he is quoted as a speaker endorsing violent subversive anti-Republican strategy[42] and contributing to belligerent spirit;[43] others consider him representative of the new Carlist generation, already inclined towards authoritarianism.[44] In 1936 he was re-elected to the Cortes from the same Navarrese constituency.[45]

Insurgency and unification

_-_Fondo_Mar%C3%ADn-Kutxa_Fototeka.jpg.webp)

Arellano was heavily involved in conspiracy to overthrow the Republic; during the hectic July 1936 last-minute political negotiations between Carlist leadership and the army conspirators he sided against Fal and with the Rodeznistas, pressing almost unconditional support of the military.[46] As Rodezno's confidant he formed a pressure group which travelled to France to seek authorization from the envoy of the claimant, Don Javier.[47] The approval, though given hesitantly, proved crucial in outmaneuvering Fal, who insisted that the generals accept the Carlist conditions first.[48]

During initial days of the insurgency Arellano stayed in Pamplona, mostly co-ordinating recruitment to the Carlist militia.[49] Some time in late July he joined the Requeté himself;[50] in unidentified unit[51] he served as junior officer in Sierra de Guadarrama.[52] It is not known whether he was engaged in combat; according to accounts available he acted mostly as a liaison officer, travelling almost every day to Navarre and back until mid-August 1936,[53] when he assisted his sister and mother, released from prison in the Republican zone, to settle in Pamplona.[54] He did not enter either the national Carlist wartime executive, Junta Nacional de Guerra, or the Navarrese Junta Central Carlista de Guerra,[55] but in the summer of 1936 the latter delegated him to Gabinete de Prensa of Junta de Defensa Nacional;[56] in early 1937 he entered Delegación de Cuestiones Sociales set up by Junta Central.[57] Some sources claim he was definitely withdrawn from the frontline in the rank of a captain in the first days of 1937[58] and indeed in January he was again in Pamplona.[59]

When pressure on unification started to mount Arellano again sided with Rodezno;[60] by some scholars he is even considered co-leader of the Rodeznistas,[61] pressing compliance and advocating the Carlist entry into a new partido unico. During charged meetings of February, March and April he enjoyed "voz cantante"[62] when pushing the intransigent Fal into minority.[63] Conscious of Carlist junior position within the coalition, he argued that sacrifice of the Requeté should not be wasted by allowing total Falangist predomination in a new monopolist state party.[64] Even in case its program had little to do with Traditionalist ideario, he calculated that after the war Carlism would regain the lost ground.[65] Apparently he did not realize the terms of forthcoming amalgamation; in the last-minute attempt as representative of Carlist labor structure Obra Nacional Corporativa Arellano was delegated to negotiate unification conditions.[66]

In April 1937 Arellano formed part of the pressure group which visited the regent-claimant and Fal in Saint-Jean-de-Luz and presented them with sort of an ultimatum, forcing Don Javier and his jefe delegado into silence.[67] Viewed favorably in Franco headquarters, he was however not member of the close circle informed about the date of the forthcoming Unification Decree.[68] The document nominated him into Secretariat, executive of the newly created Falange Española Tradicionalista; within this 10-member body Arellano was one of 4 Carlists nominated,[69] becoming top dignitary of the just emergent Francoist regime.

Early Francoism

.jpg.webp)

Though in the Carlist media Arellano was one of the faces of unification,[70] he was amazed by declared terms of the process; immediately following Decreto de Unificación he travelled to Franco to voice his disgust.[71] Bombarded with queries and protests from Carlists who found themselves marginalized in FET,[72] after 3 months he and Rodezno ceased to take part in what they considered largely fictitious meetings of the Secretariat.[73] Their relations with Don Javier remained extremely tense yet not broken;[74] it was only after in November 1937 Arellano had accepted seat in a 50-member Consejo Nacional[75] that the claimant declared him one of key rebels against his authority and expulsed them from Comunión Tradicionalista.[76]

Arellano together with López Bassa co-headed Comisión de Organización Sindical, set up by the Falangist Secretariato; the body was entrusted with drafting theoretical framework for labor organization in the new regime. At this position Arellano pursued a Traditionalist corporative vision,[77] but he was confronted by hard-line Falangist members like Joaquín Miranda and Pedro González Bueno, who advanced their idea of sindicatos verticales. As in December 1937 the Secretariat ceased to function and Arellano moved to new job, his plans were eventually dumped.[78] When in early 1938 Rodezno assumed Ministry of Justice in the first Francoist government, Arellano followed him as sub-secretary[79] - the post initially offered to José María Valiente, but rejected - and held it until the cabinet was reorganized and Rodezno replaced by Esteban Bilbao in August 1939; 70 years later this service cost him charge of committing crimes against humanity[80] He was getting increasingly disillusioned with the new party, trying to save what was left of Carlist assets and becoming shareholder of El Pensamiento Navarro, spared amalgamation by turning it into a commercial newspaper.[81] During his last months in Consejo Nacional he tried to oppose regulations aiming at total state control of the economy.[82] As his mandate was not renewed, in the early 1940s he fell out of the Francoist political elite.

Little is known about Arellano's public activity in the 1940s; holding no official posts he remained an important figure in Navarrese political realm,[83] especially that his promoter Rodezno was at that time vice-president of Diputación Provincial.[84] Apart from his engagement in private businesses,[85] Arellano was legal assessor of the Navarrese self-government, got involved in work on setting up Institución Principe de Viana[86] and remained busy assembling compilation of traditional local regulations, commissioned by the Diputación.[87] In the mid-1940s he was involved in promotion of fuerista establishments, climaxing in congress of regionalist lawyers in Montserrat.[88] Though outside intransigent Carlism headed by don Javier,[89] he remained one of key figures in the wider Traditionalist realm. Along Rodezno he formed the faction advocating that don Juan, son of the deposed Alfonso XIII, is considered a legitimate Carlist heir. Among other so-called Juanistas Arellano visited him in the Estoril residence in 1946. He co-drafted Bases de Estoril,[90] a document signed by don Juan; though very much embracing Traditionalist principles,[91] it fell short of declaring him the legitimate Carlist pretender.[92]

Mid-Francoism

In semi-free elections of 1951 Arellano got voted into the Pamplona ayuntamiento[93] and was accordingly entrusted with assignments to numerous municipal initiatives, like Caja de Ahorros Municipal de Pamplona.[94] Following the 1952 death of Rodezno many looked to Arellano as to the next informal leader of collaborative pro-Juanista Carlists; possibly to enhance his position, Franco awarded him with the prestigious Gran Cruz Meritísima de la Orden de San Raimundo de Peñafort[95] and appointed to the 1943-created Cortes Españoles, the Francoist quasi-parliament.[96] In 1953 Arellano was admitted by Franco during a personal audience.[97] Re-emergent position enabled him to engage successfully in prolonged effort to repel the Falangist takeover of the local Navarrese administration; the conflict climaxed in 1954 when the Falangist Gobernador Civil, Luis Valero Bermejo, requested that Ministry of Interior administers special measures against Arellano.[98] The showdown ended with Bermejo recalled to Madrid and total victory of the Navarrese.

Active within a broad Carlist realm, Arellano pursued an ambiguous and complex policy. Within Navarre he tried to counter the influence of Fal Conde by supporting the iconic local Baleztena family, generally loyal to Don Javier but displaying a fairly independent stand.[99] On the national scene he did not succeed Rodezno as key carlo-franquista, the role assumed rather by Esteban Bilbao and Antonio Iturmendi. He did, however, emerge as leader of the Juanistas.[100] When the Javierista cause got reinvigorated by the 1957 fulminant appearance of Don Carlos Hugo during the annual Montejurra gathering, the Juanistas mounted a counter-action; late that year Arellano presided over delegation of 50-odd Carlists who visited Don Juan in his Estoril residence and declared him legitimate Carlist successor.[101] Arellano himself entered the Private Council of the pretender.[102] In 1958 together with the Minister of Interior Camilo Alonso Vega he engineered a scheme to control the successive Montejurra gathering. Potential attendants from beyond Navarre were banned from travelling[103] and Arellano himself appeared during the feast. The plot backfired; angry Javierista youth threatened Arellano, who had to leave protected by Guardia Civil;[104] Montejurra became a promotional stage for Carlos Hugo during the next 10 years.

At the turn of the decades Arellano remained one of key Navarrese politicians. Though no longer member of Consejo Nacional, he was assured seat in the Cortes from the pool reserved for personal Franco's appointees; until mid-1960s he was not acknowledged as taking part in major legislative work or any related back-stage political haggling between different Francoist pressure groups.[105] In 1960 he was involved in promoting so-called Fuero Recopilado de Navarra, a legislative attempt launched by Diputación Foral and aiming at consolidation of Navarrese civil code and its integration into the Spanish legal framework; he served as a liaison between the Navarros and Minister of Justice Iturmendi.[106] Within the process he formally represented Pamplona lawyers, as he grew to dean of Colegio de Abogados of the Navarrese capital.[107] As a lawyer he was also involved in a number of commercial enterprises, like Goysa-Walsh, Fuerzas Eléctricas de Navarra, El Irati and others.[108]

Last years

In the early 1960s Don Carlos Hugo posed as a Francoist; his supporters pursued a policy of approaching the Falangist syndicalists, attempting to firmly mount the prince in political milieu of the regime and to enhance his chances of becoming a Francoist monarch in the future. When executing the strategy they tried to engage Carlists well adapted within the regime. It is not clear why Arellano, member of Don Juan's private council and a leading Carlist Juanista, fell into this trap. During the 1963 Sanfermines he agreed to host Princess Irene[109] in what was a carefully planned Huguista plot. The event was staged as if she and Don Carlos Hugo had first met there, a romantic gloom envisioned as a marketing trick to attract attention of national media.[110] The maneuver was repeated in 1964, again with Arellano engaged. Following running of the bulls - with Don Carlos Hugo taking part in a carefully arranged publicity stunt – Arellano attended an evening cocktail party to honor the prince. However, events got out of control; young Huguistas, unaware of the plot, assaulted Arellano in the Tres Reyes hotel lobby,[111] which terminated his brief rapprochement with the Javieristas.[112]

With his Cortes ticket renewed as Franco's appointee in 1961[113] and 1964,[114] in the mid-1960s Arellano turned into a slightly more active member of the legislative. He entered Comisión de Leyes Fundamentales, discussed new Ley Organica del Movimiento[115] and engaged in work on law on religious liberties;[116] all of them were increasingly watering down authoritarian model of the regime,[117] though Arellano was probably lacking sufficient political weight to engage in the backstage political wrestling.

.jpg.webp)

In 1966 Arellano received serious injuries in a traffic incident in Pamplona; apart from minor fractures, he suffered broken collar bones.[118] It is not clear whether the fact that in 1967 Franco did not prolong his Cortes mandate and Arellano terminated his already 15-year-long parliamentarian service was anyhow related to his deteriorating health. Still loyal to Don Juan and still member of his Private Council,[119] he was invited to major events in family of the Alfonsine claimant, like the 1967 wedding of his oldest daughter, Pilar de Borbón,[120] and especially to the 1968 christening of his first grandson, Felipé.[121] Shortly before death he was admitted to Consejo General de la Abogacia Española;[122] shortly after his passing away he was named hijo predilecto by the province of Navarre.[123]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Aránzazu Lafuente Urién, El Señorío de Los Cameros: introducción histórica e inventario analítico de su archivo, Logrono 1999, ISBN 9788489362666, p. 36

- ↑ as a number of individuals named Arellano held high positions in the Francoist Spain, especially in Navarre and Vascongadas, some of them at times get confused, e.g. Javier Sánchez Erauskin, El nudo corredizo: Euskal Herria bajo el primer franquismo, Tafalla 1994, ISBN 9788481369144, p. 75, claims that Luis Arellano was civil governor of Gipuzkoa during the early Francoism. In fact, it was Jose Maria Arellano Igea

- ↑ Ana María Aicua Iriso, El gobierno municipal en la villa de Caparroso a fines del antiguo régimen (1775-1808): hijosdalgos y labradores, [in:] Carmen Erro Gasca (ed.), Grupos sociales en Navarra. Relaciones y derechos a lo largo de la historia, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788477680895, p. 185

- ↑ Juan Peris Torner, Ferrocarril del Irati – de Pamplona a Sangüesa y ramal a Aoiz, [in:] Ferrocariles de Espana, 05.05.12, available here Archived 2018-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Vicente Pinilla Navarro, Gestión y usos del agua en la cuenca del Ebro en el siglo XX, Zaragoza 2008, ISBN 9788477339977, pp. 228-248

- ↑ Hidráulica de Moncayo was a small power-generation company relying on the Queiles river and founded in 1909, Josean Garrués Irurzun, Empresas y empresarios en Navarra: la industria eléctrica, 1888-1986, Pamplona 1997, ISBN 9788423516575, p. 311

- ↑ Josean Garrues Irurzun, Merito y problemas de las electricas pioneras: Arteta, [in:] Historia Industrial 31 (2006), p. 98

- ↑ it evolved from Huici, Múgica y Cía company, Josean Garrués Irurzun, Empresas y empresarios en Navarra: la industria eléctrica, 1888-1986, Pamplona 1997, ISBN 9788423516575, p. 86

- ↑ José Ignacio Martínez Ruiz, Trilladoras y tractores: energía, tecnología e industria en la mecanización de la agricultura española, 1862-1967, Barcelona 2000, ISBN 9788447205783, p. 142

- ↑ Irurzun 1997, p. 63. In 1934 the company transformed into sociedad anonima, Martínez Ruiz 2000, p. 142

- ↑ he was listed as number 3 on the list of shareholders of power generation companies, Irurzun 1997, pp. 209, 211

- ↑ 1931 became inspector general del Cuerpo of Confederación Sindical Hidrográfica del Ebro and president of the Sección, Pinilla Navarro 2008, p. 153

- ↑ see Juana Dihinx Vergara entry [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- ↑ Josean Garrues, Merito y problema de las electricas pioneras: Arteta, 1893/98 - 1961, [in:] Historia Industrial 31 (2006), p. 98

- ↑ due to works on Salto de Azánigo on the Gállego river, compare his account of the work completed at Revista de Obras Publicas online service, available here

- ↑ Pablo Larraz Andía, Víctor Sierra-Sesúmaga Ariznabarreta, Requetés: de las trincheras al olvido, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788499700465, p. 141

- ↑ José Miguel de Mayoralgo y Lodo, Movimiento nobiliaro ano 1936, p. 9, available here

- ↑ Arellano Dihinx Luis entry [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online service, available here Archived 2014-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Mayoralgo y Lodo 1936, p. 31

- ↑ Eduardo Aburto Uribe entry [in:] carleslopezcerezuela service, available here

- ↑ Luis Arellano Dihinx entry [in:] Geni generalogical service, available here, ABC 04.08.04, available here

- ↑ Luis Arellano - fully aware of the forthcoming coup - did not inform his family. However, he arranged their transfer from Pamplona to Fuenterrabia, assuming that in case of defeat, they would be safer at the French frontier than in the Navarrese capital. His calculations proved wrong and his mother, sister and two brothers were detained in Fuenterrabia. Females were soon released, but Francisco Javier (born 1910) and José Marí (born 1917) were executed in the first days of 1937, Larraz Andía, Sierra-Sesúmaga 2011, pp. 141-150

- ↑ ABC 10.03.82, available here

- ↑ Larraz Andía, Sierra-Sesúmaga 2011, pp. 141-150

- ↑ Alfonso Ballestero, José Ma de Oriol y Urquijo, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788483569160, p. 40

- ↑ Ana Serrano Moreno, Las elecciones a Cortes Constituyentes de 1931 en Navarra, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 50 (1989), p. 710, referring after Diario de Navarra 26.06.31. It is not entirey clear whether it was indeed Luis Arellano in question, though the fact that he spoke along other Carlists and the event took place in Eastern Navarre, where he remained active also later on, makes it very probable, compare El Siglo Futuro 19.01.33, available here

- ↑ Robert Vallverdú i Martí, El Carlisme Català Durant La Segona República Espanyola 1931-1936, Barcelona 2008, ISBN 9788478260805, p. 101

- ↑ Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349, p. 95, also Alberto Garcia Umbon, Elecciones y partidos politicos en Tudela 1931-1933, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 50 (1989), p. 248; he is also dubbed "lugarteniente" in Luis Arellano Dihinx entry [in:] Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online, available here

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 332

- ↑ see also official Cortes service, available here

- ↑ Josep Carles Clemente, Seis estudios sobre el carlismo, Madrid 1999, ISBN 9788483741528, p. 25

- ↑ José Luis de la Granja Sainz, Nacionalismo y II República en el País Vasco: Estatutos de autonomía, partidos y elecciones. Historia de Acción Nacionalista Vasca, 1930-1936, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788432315138, p. 577

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 191

- ↑ Emilio Majuelo Gil, Angel Pascual Bonis, Del catolicismo agrario al cooperativismo empresarial. Setenta y cinco años de la Federacíon de Cooperativas navarras, 1910-1985, Madrid 1991, ISBN 8474798949, pp. 187-9

- ↑ Alberto Garcia Umbon, Tudela, desde las elecciones de febrero de 1936 hasta el inicio de la Guerra Civil, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 234 (2005) p. 239

- ↑ Majuelo, Bonis 1991, p. 200

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 126, 334, Vallverdú 2008, p. 102

- ↑ Victor Manuel Arbeloa Muru, De la Comisión Gestora a la Diputación Foral de Navarra (1931-1935), [in:] Principe de Viana 260 (2014), pp. 603, 605, 608, 609, 611, 616

- ↑ Julio Aróstegui, Combatientes Requetés en la Guerra Civil española, 1936-1939, Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788499709970, pp. 80-81

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 207, 209, Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, p. 315

- ↑ according to himself, its objective was "formación cultural y fisica de los jóvenes" in combative spirit, Eduardo González Calleja, Contrarrevolucionarios, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788420664552, p. 196

- ↑ assuming that the ensuing official repressions were merely strengthening the organization, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 95

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 185

- ↑ Roberto Villa García, Las elecciones de 1933 en el País Vasco y Navarra, Madrid 2007, ISBN 9788498491159, p. 73

- ↑ see the official Cortes service, available here

- ↑ Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657, p. 18, Javier Ugarte Tellería, La nueva Covadonga insurgente: orígenes sociales y culturales de la sublevación de 1936 en Navarra y el País Vasco, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788470305313, pp. 85-6

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 248, Ballestero 2014, p. 45

- ↑ Antonio de Lizarza Iribarren, Memorias de la conspiración, [in:] Navarra fue la primera 1936-1939, Pamplona 2006, ISBN 8493508187, p. 106

- ↑ Ugarte Tellería 1998, pp. 91, 105, Aróstegui 2013, p. 123

- ↑ Luis Arellano Dihinx entry [in:] Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 260

- ↑ an Arellano is mentioned as member of Compaña de San Fermín (later incorporated into Tercio de Lesaca), Aróstegui 2013, p. 297

- ↑ Javier Ferrer Arellano, La monarquía que prometió D. Juan...tan diferente de la que tenemos. El Acto de Estoril de 1.957, [in:] javierfarellano service 18.02.12, available here

- ↑ Ricardo Ollaquindia, Pormenores organizativos de la guerra de 1936 en cartas de un Requte de Sangüesa, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 210 (1997), p. 157

- ↑ Larraz Andía, Sierra-Sesúmaga 2011, pp. 141-150; Arellano is not mentioned as travelling late September 1936 to Viena to attend the funeral of Don Alfonso Carlos, see Ignacio Romero Raizábal, Boinas Rojas en Austria, Burgos 1936

- ↑ he is not listed by detailed studies of not listed either by Peñalba Sotorrío 2013 or Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523

- ↑ Ricardo Ollaquindia Aguirre, La Oficina de Prensa y Propaganda Carlista de Pamplona al comienzo de la guerra de 1936, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 56 (1995), pp. 485-6

- ↑ Luis Arellano Dihinx entry [in:] Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online

- ↑ La Vanguardia 22.05.69, available here; some scholars list him as " significant requeté commander", Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 271

- ↑ Lizarza Iribarren 2006, p. 150

- ↑ Iker Cantabrana Morras, Lo viejo y lo nuevo: Díputación-FET de las JONS. La convulsa dinámica política de la "leal" Alava (Primera parte: 1936-1938), [in:] Sancho el Sabio 21 (2004), p. 167

- ↑ Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 43

- ↑ Manuel Martorell Pérez, Navarra 1937-1939: el fiasco de la Unificación, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 69 (2008), p. 444, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 39

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 285, c Josep Carles Clemente, Historia del carlismo contemporaneo, Barcelona 1977, ISBN 9788425307591, p. 30. It is not clear whether Arellano engineered an odd incident in March, when sitting of Concejo de Tradicion in Burgos was accompanied by 30 requetés from Navarre, apparently an intimidation attempt aimed against those opposing unification, Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 126

- ↑ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, pp. 265-7

- ↑ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 274

- ↑ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 268

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 288

- ↑ unlike Rodezno, Berasain, Ulibarri and Conde de Florida, Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 45

- ↑ along Rodezno, Florida and José María Mazón SainzBlinkhorn 2008, p. 194, Canal 2000, p. 339, Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, pp. 51-2

- ↑ articles on unification in El Pensamiento Navarro were accompanied by the photos of Arellano and Rodezno, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 291

- ↑ Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 54

- ↑ José Antonio Parejo Fernández, Falangistas y requetés: historia de una absorción violenta, [in:] María Encarna Nicolás Marín, Carmen González Martínez (eds.), Ayeres en discusión: temas clave de Historia Contemporánea hoy, Madrid 2008, ISBN 9788483717721, pp. 12, 16

- ↑ Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 133, Stanley G. Payne, Fascism in Spain, 1923-1977, Madison 1999, ISBN 9780299165635, p. 277

- ↑ initially don Javier was inclined towards compromise, assuming good faith of Rodezno, Arellano and the others, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 297, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 46

- ↑ as one of 11 or 12 Carlists; the difference stems from the fact that some scholars count in Fal, who was offered the seat but refused to take it

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, pp. 293-4

- ↑ he called in the labor code experts like Sancho Izquierdo, Eduardo Aunós or Ramón Ruiz Alonso

- ↑ Angela Cenarro Lagunas, Introducción a la edición digital de "Obrerismo", [in:] Institución Fernando El Catolico 2010, p. 24, available here

- ↑ Luis Arellano Dihinx entry [in:] Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia online, Arellano Dihinx Luis entry [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online, Jeremy MacClancy, The Decline of Carlism, Reno 2000, ISBN 9780874173444, p. 76

- ↑ in 2008 the Audiencia Nacional judge Baltazar Garzón posthumously raised the crimes against humanity case against Arellano and many other Francoist dignitaries; the charges related to his tenure in the Ministry of Justice in 1938-1939, but failed due to procedural reasons, see El Mundo 18.11.08, available here. Afterwards Garzón was charged with perversion of justice, see here

- ↑ Arellano kept 150 of the 600 shares and after Rodezno remained the second largest shareholder, Aurora Villanueva Martínez, Organizacion, actividad y bases del carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo [in:] Geronimo de Uztariz 19 (2003), p. 115

- ↑ Ballestero 2014, p. 65

- ↑ e.g. in 1939 Serrano asked him to prevent Carlist demonstrations during Sanfermines, Martorell Pérez 2009, pp. 175-6

- ↑ Villanueva Martínez 2003, pp. 103, 113

- ↑ in 1948-1955 he was member of Concejo de Administración of another Navarrese hydropower company Fensa, Garrués Irurzun 1997, p. 242

- ↑ Institución Principe de Viana entry [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online service, available here

- ↑ see correspondence of Manuel Irujo, available here

- ↑ Acta de la reunión de foralistas en el monasterio de Monserrat (1947), available here Archived 2012-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ in November 1942 Fal declared amnesty on all FET members and invited them back to Comunión provided they break any links with Falange; the scheme explicitly excluded a number of leaders, but Arellano was not listed among them, Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 143

- ↑ he was one of the co-editors of the text, Santiago Martínez Sánchez, El Cardenal Pedro Segura y Sáenz (1880-1957), [PhD thesis at Universidad de Navarra], Pamplona 2002, p. 448

- ↑ Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962-1977, Pamplona 1997; ISBN 9788431315641, p. 23

- ↑ its declared foundations were religion, unity, monarchy and organic representation, Martínez Sánchez 2002, pp. 448-9

- ↑ from Tercio de Cabezas de Familia, a pool reserved for males meeting some stringent criteria for heads of family, ABC27.11.51, available here

- ↑ Arellano Dihinx Luis entry [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online, Eduardo González Calleja, La prensa carlista y falangista durante la Segunda República y la Guerra Civil (1931-1937), [in:] El Argonauta Espanol 9 (2012), p. 29

- ↑ ABC 01.04.52, available here

- ↑ see the official Cortes service, available here

- ↑ ABC 17.12.53, available here

- ↑ Maria del Mar Larazza Micheltorena, Alvaro Baraibar Etxeberria, La Navarra sotto il Franchismo: la lotta per il controllo provinciale tra i governatori civili e la Diputacion Foral (1945-1955), [in:] Nazioni e Regioni 1 (2013), p. 116

- ↑ Mercedes Vázquez de Prada Tiffe, El papel del carlismo navarro en el inicio de la fragmentación definitiva de la comunión tradicionalista (1957–1960), [in:] Príncipe de Viana 72 (2011), p. 395

- ↑ with Arauz de Robles, Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El final de una ilusión. Auge y declive del tradicionalismo carlista (1957-1967), Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788416558407, p. 83

- ↑ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 301-2, Clemente 1977, p. 299, Caspistegui 1997, pp. 24-5, Canal 2000, p. 361. As member of El Pensamiento Navarro board he clashed with the Baleztenas but managed to override them and get the newspaper to publish so-called Acto de Estoril, Vázquez de Prada 2011, p. 402

- ↑ Arellano Dihinx Luis entry [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online

- ↑ Manuel Martorell Pérez, Carlos Hugo frente a Juan Carlos. La solución federal para España que Franco rechazó, Madrid 2014, ISBN 9788477682653, p. 93

- ↑ Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 419

- ↑ though at times he allowed himself minor dissent and voting against governmental proposals, see ABC 26.02.53, available here

- ↑ see correspondence of Manuel Irujo, available here, Compilación del derecho privado entry [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online, available here

- ↑ Arellano Dihinx Luis entry [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online

- ↑ Juan Muñoz Martín, El poder de la banca en España, Madrid 1969, p. 12

- ↑ La Vanguardia 11.06.63, available here

- ↑ Javier Lavardín [José Antonio Parilla], Historia del ultimo pretendiente a la corona de España, Paris 1976, pp. 174-176

- ↑ Lavardín 1976, p. 240

- ↑ in 1964 he already featured in media counter-offensive against Don Carlos Hugo, see ABC 09.02.64, available here, also Lavardín 1976, pp. 200-201

- ↑ see his 1961 mandate at official Cortes service, available here

- ↑ see his 1964 mandate at official Cortes service, available here

- ↑ ABC 01.06.67, available here

- ↑ ABC 11.03.67, available here

- ↑ in 1964 he was again received by Franco, ABC 19.03.64, available here

- ↑ ABC 11.04.66, available here

- ↑ La Vanguardia 23.05.69, available here

- ↑ La Vanguardia 11.05.67, available here

- ↑ La Vanguardia 09.02.68, available here

- ↑ La Vanguardia 08.05.68, available here

- ↑ Arellano Dihinx Luis entry [in:] Gran Enciclopedia Navarra online; unlike in case of many other Francoist dignitaries, including Franco himself, the title has not been revoked in the post-Francoist era, see Francisco Franco ya no es hijo adoptivo de Navarra, [in:] Boletín Fundación Nacional Francisco Franco 134 (2015), p. 22

Further reading

- Victor Manuel Arbeloa Muru, De la Comisión Gestora a la Diputación Foral de Navarra (1931-1935), [in:] Principe de Viana 260 (2014), pp. 589–630

- Martin Blinkhorn, 'Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 1975, ISBN 9780521207294

- Maria del Mar Larazza Micheltorena, Alvaro Baraibar Etxeberria, La Navarra sotto il Franchismo: la lotta per il controllo provinciale tra i governatori civili e la Diputacion Foral (1945-1955), [in:] Nazioni e Regioni, Bari 2013, ISSN 2282-5681

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis], Valencia 2009

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, Retorno a la lealtad; el desafío carlista al franquismo, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788497391115

- Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657

- Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523

- Roberto Villa Garcia, Las Elecciones de 1933 en El País Vasco y Navarra, Madrid 2006, ISBN 9788498491159

- Aurora Villanueva Martinez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714

- Aurora Villanueva Martinez, Organizacion, actividad y bases del carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo [in:] Geronimo de Uztariz 19, pp. 97–117

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada Tiffe, El papel del carlismo navarro en el inicio de la fragmentación definitiva de la comunión tradicionalista (1957–1960), [in:] Príncipe de Viana, pp. 393–406