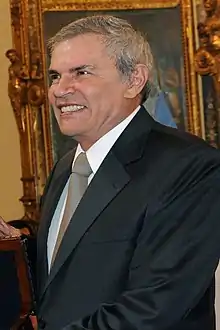

Luis Castañeda | |

|---|---|

Castañeda in 2010 | |

| Mayor of Lima | |

| In office 1 January 2015 – 31 December 2018 | |

| Preceded by | Susana Villarán |

| Succeeded by | Jorge Muñoz |

| In office 1 January 2003 – 11 October 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Alberto Andrade |

| Succeeded by | Marco Parra (interim) |

| Lima City Councilman | |

| In office 1 January 1981 – 31 December 1986 | |

| President of National Solidarity | |

| In office 5 May 1998 – 29 August 2020 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Rafael López Aliaga |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Óscar Luis Castañeda Lossio 21 June 1945 Chiclayo, Lambayeque, Peru |

| Died | 12 January 2022 (aged 76) Lima, Peru |

| Political party | Independent (2020-2022) |

| Other political affiliations | National Solidarity (1998-2020) |

| Spouse | Rosario Pardo Arbulú |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (LL.B.) Centro de Altos Estudios Militares del Perú (M.A.) |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Óscar Luis Castañeda Lossio (21 June 1945 – 12 January 2022) was a Peruvian politician who was the Mayor of Lima, the capital city of Peru, from 2003 to 2010. He became Mayor of Lima again in 2015, after being elected for a third nonconsecutive term with 51% of the popular vote, for a term that lasted until 31 December 2018. He ran for President of Peru twice, in the 2000 elections placing fifth, prior to his mayoral campaign in 2002, and in the 2011 elections, placing fifth again with 9.8% of the vote.[1]

He was placed under investigation in 2019 for alleged corruption in the context of a broad anti-corruption campaign following revelations in the Lava Jato scandal in Brazil. In particular, he was suspected of having favoured a Brazilian multinational civil engineering corporation (Grupo OAS) in exchange for bribes while serving as mayor of Lima.[2] On 14 February 2020, Judge Maria de los Angeles Camacho ordered 24 months of preventive detention for this case against the former mayor.

Early life and education

Castañeda, who was born in Chiclayo and lived in the Casa Castañeda, was the son of Carlos Castañeda Iparraguirre and Ida Lossio. His father is remembered as having been one of the most important mayors of Chiclayo. As a child he used to inspect with his father the works in progress in the city. From his marriage with Rosario Pardo, he has two sons: Luis Castañeda Pardo and Darío Castañeda Pardo.

He studied law at the Catholic University of Peru and he earned a master's degree at the Centro de Altos Estudios Militares del Perú. In Sweden and Mexico he got a Professional Diploma in Management.

Political career

In 1981, he began his political career as a member of Popular Action party, working with many of the past mayors of Lima such as Alfonso Barrantes Lingán.

Between 1990 and 1996, during the presidency of Alberto Fujimori, he was the President of the National Institute of Public Health IPPS, now known as ESSALUD. He also had a controversial participation in La Caja del Pescador, an entity that works to benefit fishermen.[3]

First presidential run (2000)

In 2000, he ran as a candidate of his own party, the National Solidarity Party, in the presidential elections, but failed to make it to the run-off elections, faring poorly in the election.[4][5]

First term as Mayor of Lima (2003–2010)

In 2002, he participated in the municipal elections for mayor with the National Unity, defeating incumbent Mayor Alberto Andrade of We Are Peru. Castañeda started out as a very popular mayor, with an approval rating close to 79%. He won re-election as the city's mayor in the November 2006 mayoral election with almost 48% of the vote against Pastor Humberto Lay’s 15% of the vote. In October 2010, he resigned as mayor of Lima to run again for the country's presidency in Peru's 2011 general elections, this time under the National Solidarity Alliance's banner-head.

Second presidential run (2011)

In 2011, Castañeda decided to run for the presidency in the presidential elections, this time under the National Solidarity Alliance. Nevertheless, and unsuccessfully, he only managed to gather around 9.8% of the votes, placing fifth.

During the last months of his administration as Lima Mayor (2003-2010), he was the subject of serious accusations of illicit enrichment and corruption in the case of "Comunicore".[6] He was also criticized for the delay in construction and the cost overrun of his El Metropolitano transportation project, whose budget multiplied, and whose completion occurred in 2010, despite the fact that its inauguration was scheduled for the year 2005. Months after having received these accusations, the Judicial Power in charge of Nelly Mercedes Aranda Cañote, decided not to include the former mayor of Lima in the Comunicore case because the Prosecutor's Office provided sufficient evidence of the agreement with the aforementioned company to economically harm the municipality.

Second term as Mayor of Lima (2015–2018)

In the 2014 municipal elections, he ran for Mayor of Lima, winning the election by a landslide on 5 October, over rival and incumbent Susana Villarán in third place (10%), and surprisingly, 18% for APRA candidate Enrique Cornejo. He assumed office on 1 January 2015 and stepped down on 31 December 2018 as he declined to run for re-election.

Controversies

During the last months of his administration as Lima Mayor (2003–2010), he received serious accusations of illicit enrichment and corruption in the case of "Comunicore".[6] He has also been criticized for the delay in construction and the cost overrun of his El Metropolitano transportation project, whose budget multiplied, and whose completion occurred in 2010, despite the fact that its inauguration was scheduled for the year 2005. Months after having received these accusations, the Judicial Power in charge of Nelly Mercedes Aranda Cañote, decided not to include the former mayor of Lima in the Comunicore case because the Prosecutor's Office provided sufficient evidence of the agreement with the aforementioned company to economically harm the municipality.

He has also been criticized for the inclusion of his name in a large part of the works made during his tenure for political purposes, a fact that he has justified by stating that "you must know who did the work."[7][8][9]

In September 2011, he was included in the process for the irregular payment of 35.9 million nuevos soles to a "ghost company" during his tenure as mayor of Lima. The former mayor presented a Habeas corpus against this measure, but finally in January 2012, the 12th Criminal Court of Lima ordered that Castañeda Lossio must be prosecuted for this case.[10][11]

On 15 March 2013, audio recordings leaked to the press were broadcast over national television revealing that Luis Castañeda Lossio was indeed in charge of the campaign to recall Lima's first female Mayor, Susana Villaran.[12] Before the leaks Castañeda Lossio had publicly denied his involvement in the recall process.

In May 2014, the Anticorruption Prosecutor's Office initiated an investigation into Castañeda Lossio for the improper collection of 200,000 new soles in the years he was mayor of Lima.[13]

While mayor of Lima, Castañeda attracted criticism for various policies that were seen as retrogressive attempts to erase the legacy of his predecessor. These included erasing murals commissioned by Villarán, undoing reforms she had made to Lima's public transit system, barring the public from city council meetings, and cancelling plans to remake the banks and neighborhoods along the Rimac River in downtown Lima into a new park, the so-called Rio Verde Project.[14] Following the cancellation of the Rio Verde project, one of the neighborhoods that would have been transformed (Cantagallo) was, instead, devastated by a fire in November 2016, which forced out hundreds of Shipibo-Konibo community members.[15]

Odebrecht scandal

As of January 2020, Castañeda remained the subject of investigations into wider allegations of corruption linked to the Brazilian construction firms Odebrecht and Grupo OAS.[16][17] On 14 February 2020, Judge Maria de los Angeles Camacho ordered 24 months of preventive detention for this case against the former mayor, while José Luna Gálvez and Giselle Zegarra will have a restricted appearance for 36 months, with certain rules of conduct.

Death

Castañeda died from cardiopulmonary arrest in Lima, on 12 January 2022 at the age of 76.[18]

References

- ↑ "Resumen Nación de Elecciones Presidenciales 2011".

- ↑ "Luis Castañeda Lossio: Lo que se sabe sobre la investigación al exalcalde". 15 October 2019.

- ↑ "Noticias".

- ↑ "AllmediaNY".

- ↑ "No alliances will be made with Lima Mayor Castañeda for upcoming 2011 presidential elections, says Simon". Peruvian Times. 17 August 2009. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- 1 2 www.desdeeltercerpiso.com http://www.desdeeltercerpiso.com/2010/02/castaneda-y-comunicore/. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Castañeda justifica placas con su nombre | LaRepublica.pe". 10 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ↑ "Alquiler y venta de casas, departamentos, oficinas y terrenos en Perú". diario16.com.pe. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ↑ "Gente indecente | LaRepublica.pe". 5 January 2011. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ↑ "Vuelven a incluir a Castañeda Lossio en proceso por el caso Comunicore - Actualidad | Perú 21". 11 January 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ↑ "Luis Castañeda Lossio será procesado por el caso Comunicore | LaRepublica.pe". 5 January 2012. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ↑ "Lima, Peru's First Female Mayor Survives Recall Vote". Hispanically Speaking News. Archived from the original on 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "Fiscalía dispuso formalizar investigación contra Luis Castañeda por presunto delito de peculado | LaRepublica.pe". 27 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ↑ Tegel, Simeon (17 March 2015). "The mayor of Lima is getting compared to the Islamic State for painting over murals". Global Post. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ↑ says, Philip Brown (5 November 2016). "Thousands homeless after fire destroys shantytown in downtown Lima". Perú Reports. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ PERÚ, Empresa Peruana de Servicios Editoriales S. A. EDITORA. "Peru: Ex-Lima Mayor Castañeda confirms OAS made contributions to 2014 campaign". andina.pe (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ Perú, Redacción El Comercio (31 January 2020). "Luis Castañeda: fiscalía pide 36 meses de prisión preventiva para el exalcalde de Lima". El Comercio Perú (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ Luis Castañeda Lossio: Médico personal de exalcalde confirmó causa de su muerte (in Spanish)