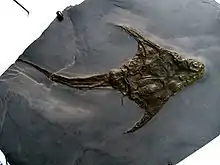

| Lunaspis Temporal range: Emsian | |

|---|---|

| |

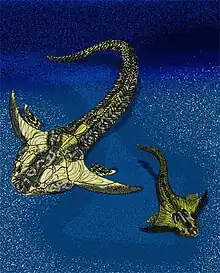

| Artist's reconstruction of L. heroldi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Lunaspis |

| Species: | L. heroldi |

| Type species | |

| Lunaspis heroldi Broili 1929 | |

| species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Lunaspis is an extinct genus of armor-plated petalichthyid placoderm fish that lived in shallow marine environments of the Early Devonian period, from approximately 409.1 to 402.5 million year ago.[1] Fossils have been found in Germany, China and Australia.[2] There are three different identified species of within the genus Lunaspis:[3] L. broilii, L. heroldi, and L. prumiensis.

Like many other petalichthyid fish, Lunaspis are flat and have elongated pectoral spines, shortened thoracic armor, and dorsally oriented eyes.[4] Lunaspis has been studied mainly by German, Australian, and Chinese palaeontologists because of where it is most commonly encountered.[2] The tails are long and thin and resemble a whip, somewhat like extant skates and rays.[4]

Description

A typical individual of Lunaspis was a flattened fish with a short trunk and long, curved cornual plates. These long, spine-like plates give the suggestion of a crescent moon, hence the generic name (moon-shield). The nostrils and the anterior part of the head shield around the orbits is covered by a number of tiny scales, as is the elongated trunk.

Lunaspis were marine bottom dwelling creatures, like many other Devonian placoderm fish, and were nektonic carnivores. The body shape of Lunaspis is also similar to other petalichthyid fish, compressed dorsoventrally.[4] Its body consists of a short trunk shield and elongated cronual plates (the wing-like structures that make up the crescent shape of the moon-like head). The rest of the body, which excludes those parts covered in the enlarged plates of armor, are covered in tiny scales, as is the anterior region of the face near the orbits and nostrils.[2] Lunaspis also has two traits that are thought to be primitive, or ancestral: large submarginal plates[5] and the occurrence of a ventral pit on the median dorsal plate.[6]

Bony armor

According to specimens examined from the Taemas-Wee Jasper region of New South Wales in Australia, both L. broilii and L. herolfi have tubercles of the median dorsal plate coalesce into a distinct median dorsal ridge (MDR). The fusion of the tubercles is unique to Lunaspis in the order Petalichthyida, where other devonian fish in this order have ornament tubercles that are separately occurring.[7] The maximum height of the ridge is reached before the posterior margin of the median dorsal plate. The spinal plates are curved and are the wings off of the center part of the bony armoring. They have many small spines along the anterior ridge of spinal plates. The ornament ridges on the bony plates make it easily distinguishable from other petalichtyid fish. These ornament ridges are widely spaced and continuous in the Lunaspis, across the three species; in L. broilii, the ornaments are more densely packed than L. heroldi and L. prumiensis.[6]

Discovery

The generic named is a compound word combining two different Greek words: “Luna” and “aspis”. In Greek, the word “luna” means The Moon, and the word “aspis” means Round Shield. Together, luna and asp signify “moon shield”; appropriately named as the long projections from the head shield make a crescent moon-like shape.

The first specimens of L. broilii were discovered and described through the collaboration of two German palaeontologists, Walter R. Gross and Ferdinand Broili. Broili discovered L. heroldi in 1929 in Germany. In Bundenbach, Germany 1937, Broili then discovered another fossil specimen that resembled Lunaspis heroldi. At first he put into the same species as L. heroldi, but noticed a difference in morphology from the previously discovered species. Near where Broili had discovered his specimen, another palaeontologist by the name of Gross was working with another specimen of Lunaspis which he originally thought to be Lunaspis prumiensis. Gross was working with fragments of the cranial exoskeletal bones of the unidentified Lunaspis species. The palaeontologists connected soon after and compared their specimens with one another and worked together to discover the differences that existed among the existing species within the genus and were able to come to a conclusion. According to the spinal and anterior ventro-lateral anatomy of the specimens they had collected, they determined that the specimen that both of them had found was a different one than had yet been identified. This new species within the same genus as L. heroldi and L. prumiensis was named Lunaspis broilii. L. Broilii is very commonly larger than L. heroldi.

The specimens of L. broilii were originally only found in Emsian-aged Hunsruck Slate of Bundenbach, Germany,[8][1] but in 1980, Liu Shifan found specimens that are most likely identifiable as L. broilii.[9] Specimens of L. broilii have been more recently found in Reefton, New Zealand, and have been identified as closely related, if not the same as those found in New South Wales, Australia. They have been found to have the same concentrically tuberculated ridges which is typical of Lunaspis.[10] Specimens of L. heroldi are also found in similarly aged marine strata in China and Australia.

Classification

Lunaspis was originally placed within the family Acanthaspidae, but according to Walter Gross's findings in 1937, the type genus of Acanthaspidae, Acanthaspis, was synonymized with Lunaspis, and the entire family merged into the family Macropetalichthyidae. Lunaspis is currently placed among seven other Macropetalichthyids, and sister to two other families within Petalichthyida.

Paleoecology

Specimens from the Reefton, New Zealand site were found in the Waitahu Outlier near the Adam Mudstone, east of Reefton. The specimen from the Waitahu Outlier was found among a multitude of invertebrate fossils, brachiopods, bivalves, orthocene nautiloids, bryozoans, and isolated crinoid stem ossicles. The Adam Mudstone spans from 407.6 to 393.3 million years ago.[10] The Adam Mudstone formation is marine and composed of silty mudstone and calcareous siltstone.[11] "The stratigraphic sequence in the Inangahua and Waitahu Outliers is essentially the same, and includes thick sandstones at the bottom and top of the succession, with an alternation of nearshore limestone and offshore mudstone formations in between. The Waitahu sequence is more continuous and is not broken by tectonic slides".[12]

References

- 1 2 Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology database. Retrieved March 6, 2017, from Fossilworks, http://www.fossilworks.org/cgi-bin/bridge.pl?page=paleodb

- 1 2 3 Benton, Michael J. (2009-02-05). Vertebrate Palaeontology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-4449-0.

- ↑ Shifan, L. (1980) Occurrence of Lunaspis in China. Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Academia Sinica.

- 1 2 3 More about Placoderms. (2002). Retrieved March 6, 2017, from Devonian Times, http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/placoderm.html

- ↑ Dupret, V., Goujet, D., & Mark-Kurik, E. (2007). A NEW GENUS OF PLACODERM (ARTHRODIRA: “ACTINOLEPIDA”) FROM THE LOWER DEVONIAN OF PODOLIA (UKRAINE). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 27(2), 266–284. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[266:ANGOPA]2.0.CO;2

- 1 2 Young, G. C. (1985). Further petalichthyid remains (placoderm fished, Early Devonian) from the Taemas-Wee Jasper region, new South Wales. BMR Journal of Australian Geology and Geophysics, 9, 121–131.

- ↑ Min, Z. (1991). New information on Diandongpetalichthys (Placodermi: Petalichthyida). EarIy vertebrates and related problems of evolutionary biology, Science Press, Beijing.

- ↑ Lehmann, W. M. (1951). Neue Beobachtungen an Lunaspis. Neues Jahrbuch Fuer Geologie Und Palaeontologie. Abhandlungen, 94(1), 93-100.

- ↑ Shifan, L. (1980). Occurrence of Lunaspis in China. Kexue Tongbao, 26(9), 828–830.

- 1 2 Macadie, I. (2007). A Placoderm Fish Plate from the Lower Devonian of Reefton, New Zealand. Records of Canterbury Museum, 21, 21–26.

- ↑ "PBDB". paleobiodb.org. Retrieved 2023-09-07.

- ↑ Bradshaw, M. (1995). Stratigraphy and structure of the Lower Devonian rocks of the Waitahu and Orlando Outliers, near Reefton, New Zealand, and their relationship to the Inangahua Outlier. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 38, 81–92.