| Lyndhurst | |

|---|---|

A side view of Lyndhurst, pictured on 2011 | |

| Location | 61 Darghan Street, Glebe, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°52′39″S 151°11′25″E / 33.8774°S 151.1902°E |

| Built | 1833–1837 |

| Architect | John Verge |

| Owner | Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales |

| Official name | Lyndhurst |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 158 |

| Type | Villa |

| Category | Residential buildings (private) |

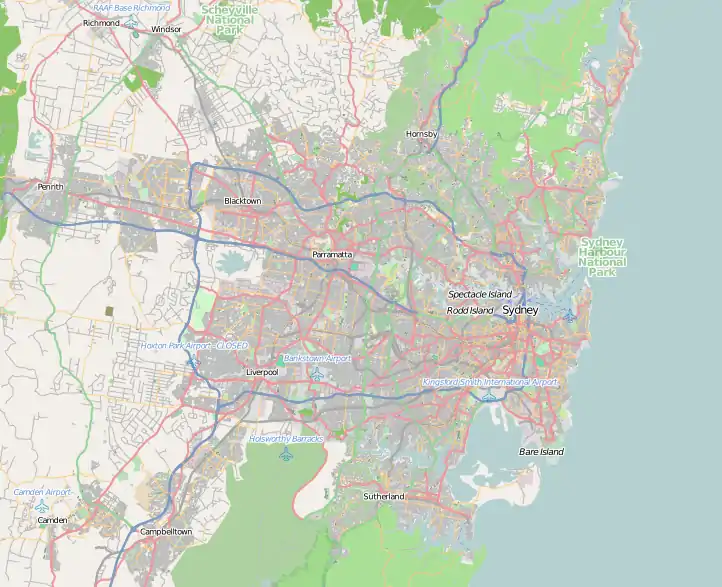

Location of Lyndhurst in Sydney | |

Lyndhurst is a heritage-listed residence and former school, laundry, maternity hospital and industrial building located at 61 Darghan Street in the inner western Sydney suburb of Glebe in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by John Verge and built from 1833 to 1837. The property is owned by Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

History

History of the area

The Leichhardt area was originally inhabited by the Wangal clan of Aborigines. After 1788 diseases such as smallpox and the loss of their hunting grounds caused huge reductions in their numbers and they moved further inland. Since European settlement the foreshores of Blackwattle Bay and Rozelle Bay have developed a unique maritime, industrial and residential character - a character which continues to evolve as areas which were originally residential estates, then industrial areas, are redeveloped for residential units and parklands.[1]

The first formal grant in the Glebe area was a 162-hectare (400-acre) grant to Richard Johnson, the colony's first chaplain, in 1789. The Glebe (land allocated for the maintenance of a church minister) comprised rolling shale hills covering sandstone, with several sandstone cliff faces. The ridges were drained by several creeks including Blackwattle Creek, Orphan School Creek and Johnston Creek. Extensive swampland surrounded the creeks. On the shale ridges, heavily timbered woodlands contained several varieties of eucalypts while the swamplands and tidal mudflats had mangroves, swamp oaks (Casuarina glauca) and blackwattles (Callicoma serratifolia) after which the bay is named. Blackwattle Swamp was first mentioned by surveyors in the 1790s and Blackwattle Swamp Bay in 1807. By 1840 it was called Blackwattle Bay. Boat parties collected wattles and reeds for the building of huts, and kangaroos and emus were hunted by the early settlers who called the area the Kangaroo Ground. Rozelle Bay is thought to have been named after a schooner which once moored in its waters.[1]

Johnson's land remained largely undeveloped until 1828, when the Church and School Corporation subdivided it into 28 lots, 3 of which they retained for church use.[2] The Church of England sold 27 allotments in 1828 - north on the point and south around Broadway. The Church kept the middle section where the Glebe Estate is now. Up until the 1970s the Glebe Estate was in the possession of the Church.[1]

On the point the sea breezes attracted the wealthy who built villas. The Broadway end attracted slaughterhouses and boiling down works that used the creek draining to Blackwattle Swamp. Smaller working-class houses were built around these industries. Abbattoirs were built there from the 1860s. When Glebe was made a municipality in 1859 there were pro and anti-municipal clashes in the streets. From 1850 Glebe was dominated by wealthier interests.[1]

Reclaiming the swamp, Wentworth Park opened in 1882 as a cricket ground and lawn bowls club. Rugby union football was played there in the late 19th century. The dog racing started in 1932. In the early 20th century modest villas were broken up into boarding houses as they were elsewhere in the inner city areas. The wealthier moved into the suburbs which were opening up through the railways. Up until the 1950s Sydney was the location for working class employment - it was a port and industrial city. By the 1960s central Sydney was becoming a corporate city with service-based industries - capital intensive not labour-intensive. A shift in demographics occurred, with younger professionals and technical and administrative people servicing the corporate city wanting to live close by. Housing was coming under threat and the heritage conservation movement was starting. The Fish Markets moved in in the 1970s. An influx of students came to Glebe in the 1960s and 1970s.[3][1]

Lyndhurst

Lyndhurst is built on part of a grant in 1796 of 162 hectares (400 acres) to Johnson on Church of England property known as the Glebe. Trustees of the Clergy and School Lands Corporation subdivided the Glebe in 1828 and Lot 5 was sold to Charles Cowper.[4][1]

The land for Lyndhurst was purchased from Cowper in 1833 by Dr James Bowman for £1500. In April NSW's foremost Greek Revival style architect John Verge selected the site and prepared designs for the residence. In May and June the plans were prepared.[4][1]

Lyndhurst house was built between 1834 and 1837 as a "suburban villa" with view to Blackwattle Bay by Verge for Bowman, the principal colonial surgeon and his wife Mary.[4] Mary was a daughter of graziers John and Elizabeth Macarthur. The house overlooked Blackwattle Bay and no expense was spared on its building or fitting out. The surviving papers and accounts would make Lyndhurst the best documented domestic dwelling of the period.[1]

In the grounds were the large service yard and balancing wings and stables designed by Verge, elaborately laid out pleasure grounds, shrubbery and the kitchen garden.[1][5]: 2–3 Francis Newman was the gardener at Lyndhurst. He was later appointed Superintendent of the Royal Society of Tasmania's garden in Hobart, which later would be renamed the Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens, a post he held form 1845 until his death in 1859.[6][1]

The Bowman's occupation of their new home did not last long. Dr Bowman had become involved with his Macarthur brothers-in-law over the Australian Agricultural Company and in 1842 was experiencing financial difficulty. The Macarthurs took possession of the property and leased it to the short-lived St James Theological College. James and William Macarthur also became indebted and the Bank of Australia took possession of it. In 1852 the bank sold the property to the Roman Catholic Church for the establishment of St Mary's College, the most important Roman Catholic School in Sydney.[7][1]

St James was Australia's first theological college and produced several distinguished native-born clerics. The success of its classical department gave Bishop Broughton, Australia's first Anglican bishop, hope that it would play a part in the emerging university movement. However, its churchmanship was considered too high and this involved a major crisis which led to its demise. St Mary's shared a similar fate. It taught secular pupils while the English Benedictine community which provided the teaching staff formed a regular order. It had a reputation for its elaborate classical curriculum and high scholarly standards. The school began to decline in the late 1860s when competition from the country catholic schools, the Irish dislike of English Benedictinism and criticism for its high fees weakened its popularity.[1][5]: 4

The college closed in 1877. In 1878 and 1885 the estate was sold, subdivided and terraced houses went up. The service wings behind the house came off, the stables demolished and the grounds built upon. Morris Asher MP, a businessman, bought the house in 1878. For some time after this the building was run as a lying-in (maternity) hospital.[1] In 1890 Asher had the verandahs and porch demolished, the main staircase removed and the interior divided into a series of small rooms and passages. Stairs were provided for each house. The houses were not successful and the interior was returned to that of one house, adding to the already confused state of the altered interior.[7][1]

During the period 1890-1905 one of the terraces became Lyndhurst Private School run by Miss Agnes Watt.[4][1]

Lyndhurst was purchased in 1925 by Aubrey Bartlett who owned it until its resumption for the freeway in 1972. By this time the building had long ceased to be a residence and had been given over to factory use. Buildings had been constructed against its walls and it served as a broom factory, soap factory, ice cream shop and joinery factory among others.[7][1] It was nearly destroyed as part of a freeway construction in 1972 but was saved by a Builders Labourers Federation green ban.[8]

Public support prompted by the Save Lyndhurst Committee for the rescue of a Verge masterpiece and a change of government led to the abandonment of the proposal and the subsequent restoration of the house by Clive Lucas, Stapleton and partners between 1979 and 1988.[4] The first brief came from the Heritage Council in 1979 to see if the wreck could be saved.[1] The Heritage Council Restoration Steering Committee inspected Lyndhurst on 26 October 1981 and the consultant project architect, Clive Lucas was asked to prepare estimates on the cost of replacement of the stairs, porch base, chimney pieces, exterior terraces and provision of a modern kitchen and toilet facilities. It was decided to approach the Department of Main Roads regarding possible acquisition of adjoining properties to ensure an adequate curtilage for Lyndhurst. Housing and exhibition at Lyndhurst of architectural records, particularly drawings, was considered as well as transfer of the John Verge-designed building to the Historic Houses Trust of NSW as its main office and a resource centre on historic interiors.[9][1]

Finance was allocated for necessary structural repairs, a temporary roof and caretakers accommodation. This halted decay and allowed for proper assessment. Initial recommendations, including restoration of the hall, dining, drawing room and library, were achieved by 1981, allowing the public to appreciate the house. In 1983 the building was transferred to the Historic Houses Trust of NSW to complete the project to provide them with a headquarters. Attention was first paid to the interiors. The last phase of the restoration was the reconstruction of the garden. This work was finished in May 1988.[7][1] The weekend of 29–30 October 1988 marked the official opening of Lyndhurst as headquarters of the Historic Houses Trust of NSW and the Conservation Resources Centre. Members of the public were invited to visit.[1][10]

In 1990 Clive Lucas Stapleton & Partners were awarded the Greenway award by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects for Excellence in building restoration.[7][1]

The property was sold before auction in 2005 to Tim Eustace and partner Salvatore Panui for $3.3m who asked Clive Lucas back to do more restoration work, adding a new kitchen and opening the property to the public occasionally. The property is back on the market in 2016 following Eustace and Panui's purchase of Iona, in Darlinghurst from film makers Baz Luhrmann and Catherine Martin.[11][1]

Description

- Site and setting

Lyndhurst is located approximately 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) south west of the Sydney CBD with a road frontage. It is a level site with city views available from the second floor. Surrounding development consists of older style semi-detached and terrace cottages on small lots and in varing condition.[1][12]

The house is set on 1,507 square metres (16,220 sq ft) of level land.[13][1]

- Garden

Lyndhurst's garden is much reduced on the original Bowman estate, which had an extensive parkland, carriage drives across what is now Wentworth Park and Blackwattle Bay's hinterland and was designed to be seen as a villa garden from the city, with the house sited on a rise, with harbour and city views. What remains is a vegetated yard to the house's north and east, wrapping around it on three sides, the southern side being predominantly paved and driveway. Darghan Street cuts very close to the house's western facade. The garden today owes much to the occupancy of the former Historic Houses Trust of NSW (now Sydney Living Museums) and input of its professional staff such as garden historian James Broadbent.[1]

It retains a number of trees including two tall mature Canary Island date palms (Phoenix canariensis) (one east of the house's garden front, one to its south), angel's trumpets (Datura (now Brugmansia) cv.s)(to the verandah's south), giant bird-of-paradise flower (Strelitzia nicolae (syn.S.alba)) on the verandah's north-eastern corner, Californian desert fan palm (Washingtonia robusta), sago palms (Cycas revoluta) in tubs and more. Wisteria sinensis has been trained up verandah posts on the house's eastern garden front. A number of large terracotta urns are planted with species such as pygmy date palm (Phoenix roebelenii), topiarised box (Buxus microphylla). Shrubs in the garden include frangipani (Plumeria x rubra cv.s), hairy sage (Salvia leucantha), NZ flax (Phormium tenax cv.), taro (Alocasia / Colocasia sp.), Nile or African lily (Agapanthus x praecox), bird-of-paradise flower (Strelitzia reginae), Camellia sasanqua cv.s and more.[14][1]

- House

It is a large two storey house raised on a semi-basement. It is five bays wide by three bays deep with three main fronts. It has a corrugated iron roof, hardwood floors and fine details. The first floor windows are all finished with architraves and the french doors which open onto a raised terrace all carry entablatures.[15][1]

Central hallway connects a suite of generous entertaining rooms, all of which have French doors opening onto wide verandahs. Features include a grand sweeping staircase, 4m high ceilings, original floors and fireplaces, modernised kitchen and bathrooms and palatially-proportioned bedrooms.[13][1]

It incorporates elements of restrained Green revival detailing which includes symmetrical planning, elevations with breakfronts and inverted pilasters at corners, classical portico, verandas, vaulted plaster ceilings and Greek Revival stone exterior and timber interior architraves.[4][1]

Condition

As at 27 August 2014, the physical condition was good.[1]

Modifications and dates

Significant developments include:[1][7][4]

- 1852 - extensive Lyndhurst Estate subdivided. St Mary's College established and an east west wing added to the eastern services wing.

- c. 1878 - Verandahs, service wings, stables and college additions demolished after subdivision. Estate around house reduced to a few metres on three sides, ringed by suburban streets.

- 1890-1905 - House subdivided into three terraces, merged into one and then divided into three terraces again.

- 1925-1972 - Buildings constructed up against the house by tenants using it as a factory.

- 1979-1988 - Restoration and reconstruction

Heritage listing

As at 2 October 1997, Lyndhurst possesses aesthetic significance as a work of architect John Verge (1782-1861); as illustrative of the history of design of villas and country houses, their positioning, gardens and estate curtilages, in NSW both in the 1830s and at other times (including its garden which while no longer extant appears to have been the first private gardens designed with professional advice, namely that of Thomas Shepherd);[1]

Lyndhurst possesses representative social historical significance as one of a series of villas and rural residences commissioned by prominent NSW families in the prosperous and optimistic 1830s; and through its commissioning and initial occupancy by James Bowman (1784-1846), a member, through his marriage to Mary Macarthur, of the prominent Macarthur family;[1]

Lyndhurst possesses specific historical associations with Anglican and Roman Catholic education and churchmanship in NSW;[1]

Lyndhurst possesses specific local significance to the Sydney suburb of Glebe;[1]

The fabric of Lyndhurst reflects changing attributes to and policies and methodologies for the conservation of heritage buildings (excerpts from NSW HHT draft CMP, 1994)[1]

Lyndhurst is an important early Sydney mansion designed by a leading architect for an important pioneer family. It is also important for the role it played in education both as a theological college and as a school. It also has importance in the conservation history of Sydney.[7][1]

The garden of Lyndhurst is significant because:

- it was a prominent example of colonial estate development;

- it was one of the first private gardens in NSW to have professional design advice;

- the extensive retention of native shrubs and trees marked a change of thought in attitudes to landscaping in the Australian environment;

- of its associations with Dr James Bowman, Principal Colonial Surgeon, and MLC; Mary Macarthur Bowman; Thomas Shepherd, Nurseryman and early Australian landscape designer; architect John Verge; and with early Australian schools.[16][1]

Lyndhurst was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

Lyndhurst possesses specific historical association with Anglican and Roman Catholic education and churchmanship in NSW. It housed St James, Australia's first Anglican Theollogical College (1847–49). The closure of St Mary's College coincided with the death of John Bede Polding, the first Roman Archbishop of Sydney. The operation of this college reflected the first phase in the history of the Roman Catholic church in Sydney, in which the English Benedictines were pre-eminent.[1]

Subdivisions of the Lyndhurst Estate in 1852, 1878 and 1885 allowed suburban development of this area of Glebe. The 1880 subdivision of the house into three terrace houses, and subsequent uses, including dwellings, girls school, maternity hospital and industrial uses represent the demographic changes in Glebe from middle class to working class housing.[1]

Lyndhurst possesses specific social history significance through its commissioning, and initial occupancy by James Bowman, a member of the Macarthur family through his marriage to Mary Macarthur. The family connection provides links between Lyndhurst and other work by Verge for the Macarthurs - Camden Park; Elizabeth Farm; The Vineyard, Parramatta and Ravensworth, Hunter Valley.[1]

The conservation and restoration of Lyndhurst 1979-1988 coincides with a period of gentrification of the suburb of Glebe.[4][1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

Lyndhurst, built 1834-37, incorporates elements of a repertoire or restrained Greek Revival detailing which Verge acquired working in London before emigrating to Australia. The quality of this detailing places Lyndhurst in the early period of Verge's work, lacking the latter refinements of Elizabeth Bay House.[1]

Lyndhurst is positioned at the western end of a ridge overlooking Blackwattle Bay (now Wentworth Park) and Johnstone's Bay, leading to references to it as a "marine villa".[4][1]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The 1979-1988 fabric of Lyndhurst reflects changing community attitudes to, and policies and methodologies for, the conservation of heritage buildings.[1]

The public support for the save Lyndhurst Committee probably reflected concern over the future quality of Glebe.[4][1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

Lyndhurst is representative of a series of villas and rural residences commissioned by prominent NSW families in the prosperous, optimistic 1830s, their positioning, gardens and estate curtilages. It is also representative of the fate of many of these houses.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 "Lyndhurst". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00158. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - ↑ City Plan Heritage, 2005, quoting Max Solling & Peter Reynolds "Leichhardt: On the Margins of the City", 1997, 14

- ↑ Murray, Dr Lisa. Central Sydney, 5 August 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Historic Houses Trust, 1994.

- 1 2 Historic Houses Trust 1984.

- ↑ Sheridan, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Historic Houses Trust, 1990.

- ↑ "List of green bans, 1971-1974". libcom.org. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- ↑ Heritage Council of NSW, 1982.

- ↑ North, Tim; North, Keva (October–November 1986). "Official Opening of Lyndhurst". Australian Garden Journal. 8 (1).

- ↑ Macken, 2–3 April 2016.

- ↑ Valuer Generals Office, n.d.

- 1 2 Sotheby's, 2016.

- ↑ Read, Stuart. "pers.comm. viewing". Retrieved 27 August 2014.

- ↑ Lucas. 1972.

- ↑ Long, 1986

Bibliography

- "Preservation Heritage Walk". 2007.

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Preservation Heritage Walk" (PDF).

- Clive Lucas, Stapleton & Partners Pty. Ltd. (1991). "Lyndhurst, Glebe: record of restoration works in two volumes". Archived from the original on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Heritage Council of NSW (1982). Annual Report 1982.

- Long, Elisha (1986). "Lyndhurst, Glebe: landscape survey and report". Archived from the original on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Macken, Lucy (2016). "'Just what the Doctor ordered', in Title Deeds: Domain". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- North, Tim; North, Keva (October–November 1986). "Official Opening of Lyndhurst". Australian Garden Journal. 8 (1).

- Reymond, Michel (1981). "Lyndhurst, 59-63 Darghan Street". Archived from the original on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Sheridan, Gwenda (2011). Insights into Tasmania's cultural landscape: the conifer connection.

- Temple, H.; Newell, L.; Young, G. (1984). "Lyndhurst, Glebe : an archaeological investigation". Archived from the original on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Young, Gregory (1988). "Lyndhurst: historical report, recommendations for interpretation, recommendations for action". Archived from the original on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Lyndhurst, entry number 158 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Lyndhurst, entry number 158 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 13 October 2018.