| Lynn Canyon Park | |

|---|---|

Lynn Creek in Lynn Canyon Park | |

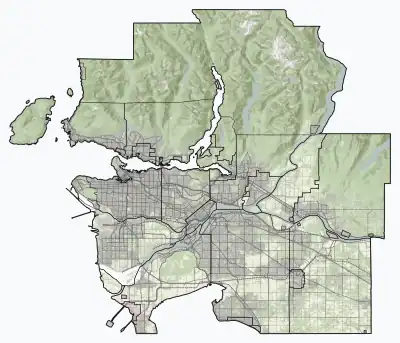

Location of Lynn Canyon Park in Metro Vancouver | |

| Location | District of North Vancouver, British Columbia |

| Coordinates | 49°20′02″N 123°01′03″W / 49.3338°N 123.0175°W |

| Area | 617 acres (250 ha) |

| Established | 1912 |

| Governing body | North Vancouver (district municipality) |

| ecologycentre | |

Lynn Canyon Park is a municipal park in the District of North Vancouver, British Columbia. When the park officially opened in 1912 it was only 12 acres (4.9 ha) in size, but it now encompasses 617 acres (250 ha). The park has many hiking trails of varying length and difficulty. The Baden-Powell Trail passes through the park crossing over the Lynn Canyon Suspension Bridge. Due to its natural landscape many TV series such as Stargate SG-1 and Stargate Atlantis used the area for filming.

History

The Tsleil-watuth people called the Lynn Creek area Kwa-hul-cha, referring to a settlement in the area. When settlers moved to North Vancouver, they began to log the old growth forests as part of Vancouver's growing logging industry. The Lynn Valley area, along with Lynn Creek and Lynn Canyon were renamed after sapper John Linn, a Royal British Engineer[1] in 1871. The Linn family name was often misspelled "Lynn". By the turn of the century Linn Creek had become Lynn Creek.

In 1910, the McTavish brothers donated 5 hectare of canyon land to the District of North Vancouver.[2] They hoped a park would attract people to their real estate development; the District of North Vancouver accepted the gift and added another 4 hectares. Walter Draycott visited the Lynn Valley on a picnic in 1911 and fell in love with the rugged wilderness. In 1912, he bought 3 lots near the canyon for $600.[2]

Designs for the Lynn Canyon Suspension Bridge were created by civil engineer and architect, C.H. Vogel. The construction of the bridge was completed in 1911. Lynn Canyon Park and the suspension bridge were officially opened at the first Lynn Valley Days celebration on September 14, 1912.[2]

As a private operation the Suspension Bridge cost 10 cents per person to cross. Later the fee was reduced to 5 cents, but the bridge fell into disrepair and was finally closed.[2] The District of North Vancouver made repairs to the bridge and reopened it, free to everyone. The Lynn Canyon Suspension Bridge is often compared to the nearby Capilano Suspension Bridge and is a local favorite. As of 2014, Lynn Canyon Park is 617 acres, making it the largest park in North Vancouver.[3]

Lynn Canyon Ecology Centre

The Lynn Canyon Ecology Centre is a building within the Lynn Canyon Park of North Vancouver, British Columbia that displays interactive exhibits about British Columbia's natural history as well as local and global environmental issues. Opened in 1971, the building is designed to resemble a Pacific dogwood blossom, the official flower of the province. The Ecology Centre is a district of North Vancouver Parks Department facility.[4] The centre is designed with the intention of creating a fun and interactive atmosphere for all ages to learn about local and global environmental issues. Admission to the facility itself is free, but a $2 donation is recommended. The facility serves a vast population. During peak tourism months, many individuals new to the city visit the Lynn Canyon Park and often take advantage of the gift shop found in the centre.[4] Other populations include students via school organized field trips as well as individuals simply interested in learning more about local and global ecology.[4]

Depending on the month, the employees at the centre offer special events for adults and children to attend. Event topics include the rainforest, birding, and urban agriculture.[4] The centre also has a theatre where they show regular educational videos. These videos can range from Magic School Bus for children, to documentaries about specific species created by experts in the field.[4] The purpose of these programs is to enhance visitor's understanding of the ecology of North Vancouver while at the same time provide an opportunity to learn more about the park. The exhibits at the centre have a wide encompassing range from the development of the forest around Lynn Canyon Park to the various species that live and thrive in the North Vancouver area. Each of the exhibits display facts about a specific aspect of the ecology of the region through use of interactive quizzes as well as life-size models. The centre features four main galleries that encompass information about plants, animals and people.[4]

Ecology of Lynn Valley

The ecology of Lynn Valley is quite vast as it expands to the entire North Vancouver area. There are several species of animals that can be found both within the Lynn Canyon Park as well as other surrounding regions such as Horseshoe Bay and the local mountains. Just like the wildlife in the area, the plant and vegetation is highly variable as the altitude of the regions change, however the majority of the vegetation in the area is a strong resemblance of Vancouver's temperate rainforest.[5]

There is a large range of vegetation that exists in Vancouver's temperate rainforest. This vegetation mostly consists of conifers with scattered pockets of maple and alder, and large areas of swampland which are even found in upland areas, due to poor drainage.[5] The conifers are a typical coastal British Columbia mix of Douglas fir, western red cedar and western hemlock. The Vancouver area is thought to have the largest trees of these species on the British Columbia Coast.

The Lynn Valley Forest is over 1000 years old and is a stable and self-replicating. Western hemlock, western red cedar, Sitka spruce, cottonwood, and broad leaf maples grow in moist valley soils. Douglas-fir and western hemlock grow on the well-drained hillsides.[4] During a drought period, the forest becomes prone to spontaneous, natural forest fires that can devastate the region. Large mammals such as bears, wolves and deer easily out distance the fire while smaller mammals often perish.[4] Two years after the fire, sun tolerant plants grow in the disturbed soil. The dead snags provide nutrients for smaller vegetation such as shrubs and small mammals such as shrews. Red-tailed hawks and other birds of prey return to the area to hunt the small mammals. 200–300 years after the fire the forest has reached an early climax stage. It is dominated by Douglas-fir, western hemlock and western red cedar. Birds and mammals such as the spotted owl, northern flying squirrel and Roosevelt elk start to present in the area in increasing numbers. If undisturbed by a major fire, storm or human activity, the forest community will gradually mature.[4] The park is a second growth forest, with the most of the oldest trees being 80–100 years old. Evidence of logging in the area can be also found in the many large stumps, complete with springboard notches.[6]

There is a multitude of wildlife in the Lynn Canyon area. One of the main concerns for human-animal interactions in the North Vancouver area arises from black bears.[7] Black bears are found in areas such as Lynn Canyon Park but also have been found to travel into residential areas in search of food.[7] More than 1000 bears are killed every year in British Columbia because of bear-human conflicts; the North Shore Black Bear Society published a year end report in 2012 to try to address this issue.[8] Although black bears are common in the Lynn Valley area many of the animals, especially the birds, will tend to migrate to different locations all around North Vancouver and can even be found as far west as Horseshoe Bay.

Lynn Valley Park offers many animal-watching tours that provide an opportunity for tourists to witness animals such as voles, Douglas squirrels and birds of prey such as the Cooper's hawk. There are also larger animals that live in the area such as black bears and black-tailed deer. However, these animals are not seen on a regular basis by tourists due to the boundaries placed on trails by park officials.

List of wildlife in the area[4]

Injuries and deaths

It was reported in 2020 that "About 20 people have died in Lynn Canyon in the past 25 years, often in cliff-jumping incidents".[9] It was also reported that "One sign [in Lynn Canyon] reports 32 deaths in Lynn Canyon between 1985 and 2016, along with many more injuries."[9]

See also

References

- ↑ "Early History of Lynn Canyon Park". Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Early days in Lynn Valley". Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ "Lynn Canyon Park Information". Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Lynn Valley Ecology Center". Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- 1 2 Vancouver

- ↑ "The History of Metropolitan Vancouver". Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Bear Awareness". North Vancouver District. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ Miller, Christine. "District of North Vancouver 2012 Year-end Report" (PDF). North Shore Black Bear Society. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- 1 2 Baker, Rafferty (29 July 2020). "'We've had fatalities': First responders ask people not to cliff jump in Lynn Canyon". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.