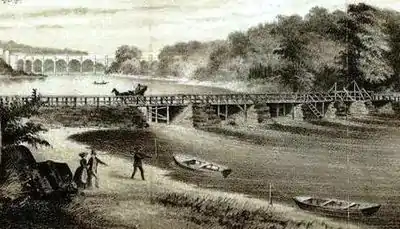

Macombs Dam (/məˈkuːmz/ mə-KOOMZ) was a dam and bridge across the Harlem River between Manhattan and the Bronx in New York City, which existed from c. 1814 to c. 1858. The bridge was later replaced with the toll-free Central Bridge, and since 1890, the current Macombs Dam Bridge has stood on the site.

History

Construction

In 1813, Robert Macomb, son of the merchant Alexander Macomb, requested permission of the New York State Legislature to build a dam[1] which would hold water for a tide powered gristmill[2] created by the new dam and another one Macomb owned near King’s Bridge on Spuyten Duyvil Creek.[3] Fifty prominent citizens of the area, realizing that Macomb would most likely receive the permission he had asked for, petitioned the city's Common Council to allow a bridge to be built as part of the structure as well. This request was granted, and Macomb was allowed to collect tolls on the bridge, half of which would go to the Council to be used to educate the poor.[3] The bridge was completed in 1816, two years after the dam had opened.[3]

As part of the permission to build the dam, Macomb was required to provide a lock to allow boats to pass, and to keep navigation on the river open.[1][3][4] But when the dam began operation in 1814, the manned lock, which was on the north side and measured only 7 by 7 feet (2.1 by 2.1 m),[3] could accommodate only small boats, limiting the river's capacity.[1] To make matters worse, by the late 1820s the lock had been partially filled in with stone, forcing boats to navigate through the piers of the bridge at high tide, a hazardous task that claimed several lives.[3]

Destruction

In 1839, local citizens,[5] angry that the river was still blocked and that the proposed crossing for the Croton Aqueduct would further block the river,[6] got legal advice and planned a response. Repeatedly, the dam was sailed to and passage requested. Each time, passage was refused as not possible, and a meticulous log was kept of the attempts. On September 14, 1839, led by Lewis G. Morris, a force of 100 men,[3] including Gouverneur Morris Jr., confronted the bridge keeper demanding passage for their vessel. When they were refused, Morris's men – who came from a chartered coal barge[1] – proceeded to breach the dam and bridge with axes, in an act of civil disobedience, allowing the bark Nonpareil to pass.[4][7][8] They returned on September 21, 22 and 24 to remove more of the dam. Their actions against the dam as a public nuisance to navigation were upheld by the courts, in Renwick v. Morris,[9] William Renwick being the owner of the dam at the time.[3] The court ruled that New York State should not have authorized the bridge to be built, because navigable waterways are the jurisdiction of the Federal government.[10]

On March 19, 1858, Senator Smith Ely Jr. introduced legislation to the New York State Senate mandating the removal of obstructions, including Macomb's Dam, from the Harlem River.[11] Its passage under Chapter 291 on April 16, 1858, directed the replacement the dam with a turntable swing bridge, to be administered by a four-person commission split between members of both Westchester and New York counties. Each county was required to pay $15,000 of the construction cost[12][3][13] By 1861 the bridge and dam had been totally removed, and the bridge was replaced with the toll-free Central Bridge.[3] In 1890, this was replaced by the current Macombs Dam Bridge, now the third-oldest major bridge in New York City, after the Brooklyn Bridge and the Washington Bridge.[1]

The Macombs Dam is memorialized in the name of Macombs Dam Park, which was rebuilt as part of the construction of the new Yankee Stadium in 2010.[1]

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Macombs Dam Park". City of New York Parks & Recreation. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2010. at the New York City Parks Department website

- ↑ Edsall, Thomas H. (1887). History of the town of Kings Bridge : now part of the 24th ward, New York City with Map and Index. New York City: Privately printed. pp. 49–53. Call number: SRLF:LAGE-1137351. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ensel, Douglas; Marchese, Shayna (March 11, 2010). "Macomb's Dam Bridge". Bridges in the New York Metropolitan Area. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- 1 2 "MACOMBS DAM BRIDGE: Historic Overview". March 11, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ Lewis G. Morris (1857). Harlaem River: its use previous to and since the Revolutionary War, and suggestions relative to Present Contemplated Improvements. New York, New York: J.D. Torrey, 13 Spruce St. p. 10. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ Gerard T. Koeppel (2000). Water for Gotham: A History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 230, 332. ISBN 0-691-08976-0. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ↑ William Cauldwell (September 23, 1900). "LEWIS G. MORRIS'S RAID: Reminiscence of His Midnight Attack on Macomb's Dam-Ruse Attended by Important Results" (PDF). The New York Times.

A Mr. Robert Macomb [...] had succeeded in getting permission to erect a dam across the Harlem River, on condition that he should consturct[sic] the dam in such a manner as to allow vessels to pass and repass and not block the navigation of the stream. Of course Macomb promised everything before he got the permission, and, is usually the case, did nothing toward the fulfillment of his promises after he got it. He constructed the dam, but he made no provision for the navigation of the river. In brief, he blocked it with his dam

- ↑ "Macombs Dam Bridge Over Harlem River". Archived from the original on June 5, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ↑ Joyce, Joseph Asbury; Joyce, Howard Clifford (1906). Treatise on the law governing nuisances. Albany, N.Y., M. Bender & co. pp. 116, 546.

- ↑ Ultan, Lloyd. "Macombs Dam" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300055366. p. 710.

- ↑ "Excitement in the Legislature" (PDF). The New York Times. March 19, 1858. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ↑ "Macombs Dam Bridge". mlloyd.org. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ↑ "City Items" (PDF). The New York Times. April 26, 1858. Retrieved June 12, 2021.