| Macrozamia heteromera | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnospermae |

| Division: | Cycadophyta |

| Class: | Cycadopsida |

| Order: | Cycadales |

| Family: | Zamiaceae |

| Genus: | Macrozamia |

| Species: | M. heteromera |

| Binomial name | |

| Macrozamia heteromera C.Moore | |

| |

| Occurrence data from AVH | |

Macrozamia heteromera is a species of cycad in the family Zamiaceae initially discovered by Charles Moore in 1858 and is endemic to New South Wales, Australia.[1] It can be found in the north-western region of New South Wales within the Warrumbungle mountains and further south west towards the Coonabarabran district. It is a low trunked cycad usually at a height below 1 metre and can be found in dry sclerophyll woodlands. M. heteromera can be distinguished from the rest of the Macrozamia genus by its mid-green, narrow, usually divided pinnae and divided seedling pinnae.[2] It is a plant that has toxic seeds and leaves, a characteristic common to cycads. However, after proper preparation and procedure, the seeds are fine for consumption.

Discovery

Macrozamia heteromera was first discovered by Australian botanist Charles Moore during a journey in 1858 where he discovered leaf specimens of the Heteromera.[3] However, as Moore was unable to collect any of the fruit, he did not have enough information to provide a thorough description of the plant.[3] It was not until the year 1882 where Moore’s assistant Ernst Betche had collected adequate specimens of the leaves and fruit of the Heteromera which upon receiving was named by Moore.[3] He described the plant as having a small trunk approximately 6–8 in (15–20 cm) long and covered with what seemed to be a red coloured wool.[3] Furthermore, its leaves were 2 ft (0.61 m) long, covered in long hairs and spirally twisted consisting of pinnae forked variously and simply around 6 in (15 cm) long.[3] At the time, Moore had believed that there were two other variations of M. heteromera.[3] He named the two variants glauca and tenuifolia.[3] The glauca was distinguishable by its longer leaves that lacked rigidity and were always glaucous and glabrous.[3] The tenuifolia’s leaves were more rigid of a dark green colour.[3] Furthermore, its pinnae forked twice and were bright red at the base.[3] However, after a small revision in 1998 by David L Jones, the glauca and tenuifolia variants became recognised as their own species under the M. heteromera complex.[2] The glauca variant became known as Macrozamia glaucophylla and the tenuifolia became Macrozamia polymorpha.[2]

Taxonomy and nomenclature

M. heteromera was first described in 1883 by Charles Moore. This was done in the 17th volume of the Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales where he described ten plants that were classified under the Macrozamia genus. Moore had named it M. heteromera after its divided pinnae that were very inconsistent in appearance.[4]

M. heteromera is one of three species originally recognised under the Zamiaceae family before David L Jones revised the M. heteromera complex in 1998.[2] The M. heteromera complex known for their divided pinnae includes Macrozamia heteromera, Macrozamia diplomera and Macrozamia stenomera. These cycads can be found close to each other, are often mistaken for one another and secluded from any other cycad.[5] This may suggest a casual correlation that plants with divided pinnae possess a slight selective advantage in their environment.[5]

Description

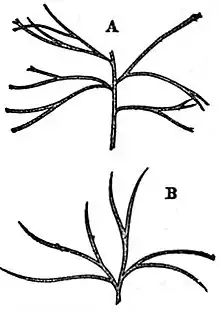

The Macrozamia Heteromera is a small low-trunked cycad that often grows to a height of less than 1 meter[3]. The stem grows up from 15–25 cm (5.9–9.8 in) in diameter and is light green in colour. It supports a crown consisting of two to eight leaves. The moderately keeled leaves can grow to around 50–90 cm (20–35 in) long and are composed of up to 60 to 100 pinnae of a dull semi-glossy mid-green colour that branches into two (i.e. the pinnules are once or twice dichotomous) which is a feature that helps to distinguish this from other species within the Macrozamia genus.[2] The Petiole ranges from 15–20 cm (5.9–7.9 in) and 6–9 millimetres (0.24–0.35 in) wide at the lowest pinna. The Rachis is not too moderately spirally twisted. Pollen cones are spindle shaped, 14–21 centimetres (5.5–8.3 in) long and 4.5–5.5 centimetres (1.8–2.2 in) in diameter along with a microsporophyll lamina that is approximately 16–21 millimetres (0.63–0.83 in) long and 12–19 millimetres (0.47–0.75 in) wide. The number of cones is very irregular, a feature of the Macrozamia species. However, on average, male plants can have up to four cones that are curved, and females have one to two of an ovoid shape.[4] Male cones typically range from 12–20 cm (4.7–7.9 in) long and up to 5 cm (2.0 in) in diameter. Similarly, females range from 20–35 centimetres (7.9–13.8 in) long, 8–12 centimetres (3.1–4.7 in) wide are up to 12 centimetres (4.7 in) in diameter and have green and pink sections on the sporophyll.[4] Inside the cones are red sacrotesta seeds of an irregular prism shape that is uniformly spread in the cycad.[2]

Distribution and habitat

Occurring on sandy, stony and infertile siliceous soils over acid volcanics and often in dry sclerophyll woodlands, Macrozamia Heteromera is an endemic species to New South Wales.[2] It can be found in north-western New South Wales in the Warrumbungle Mountains and further south west towards the Coonabarabran district.[2]

The Warrumbungle mountain range is composed of complex rocky formations, the remnants of a large heavily eroded shield volcano active from 13 to 17 million years ago.[6] The climate of Warrumbungle is temperate and warm with a significant frequency of rainfall all year round including the driest seasons. The average annual temperature and precipitation of the range is 17.1 °C and 655mm respectively.[7] The climate of Warrumbungle is classified as Cfa (Humid subtropical) with warm and wet climates according to Köppen-Geiger.[7]

Coonabarabran is a small town known as the 'Gateway to the Warrumbungles'.[8] It is at an elevation of 509m above sea level with a minimum and maximum temperature of -3.6 °C and 35.9 °C, averaging once per week in winter and summer respectively.[9] Coonabarabran has an average rainfall of 744.7mm annually, the seasonal rainfall pattern can be described as follows: Summer (32%), Autumn (23%), Winter (23%) and Spring (23%).[10][11]

Toxicity

Cycads of the Zamiaceae family are generally toxic and produce the azoxyglycoside macrozamin.[5][12] Macrozamin is composed of a primeverosa which is a disaccharide formed by glucose and xylose.[12]

Ecology

The seeds from this cycad are edible after proper preparation. The macrozamin produced by M. heteromera is the result of an evolutionary defence mechanism to prevent itself from being consumed by herbivores.[12] This allows M. heteromera to safely grow and reproduce without interference from predators (herbivores).[12] These predators could include caterpillars, cow and sheep. The Indigenous Australians utilised the cycad's seeds as a source of food.[5] They were able to remove the harmful toxins through roasting the seed and prolonged washing, resulting in an edible starchy endosperm.[5] The first reported poisoning from this cycad is believed to have occurred in 1916 within the Coonabarabran district.[13] Some fatalities of cattle had been reported and those affected had staggered and lost control of their hindquarters.[13] Only the leaves of M. heteromera were present within the paddock at the time which was reasonable enough evidence for them to believe it had been M. heteromera.[13] It was previously believed that M. heteromera had caused a mass sheep poisoning in the Coonabarabran district in 1929 where sheep had eaten the seeds of the cycad for an hour unmonitored.[14] This resulted in five sheep dying within 18 to 20 hours after consumption and death continuing for three weeks resulting in 2,200 sheep dying out of the total 6,000.[14] However, it was later confirmed that the poisoning was instead caused by Macrozamia diplomera via a veterinary report.[15] Farmers have used terms such as ‘zamia staggers’, ‘zamia rickets’ or ‘zamia wobbles’ to describe the symptoms due to cattle consuming Macrozamia seeds and leaves.[16] Farmers had coined the term ‘sheep nuts’ for M. heteromera seeds in particular.[16]

References

- 1 2 Forster, P. (2010). "Macrozamia heteromera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T42007A10619620. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-3.RLTS.T42007A10619620.en. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jones, David (1998). Flora of Australia. Vol. 48. Canberra: Australian Government Pub. Service. pp. 658–659.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Moore, Charles (1883). "Notes on the Genus Macrozamia". Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. Macquarie Centre Soc. 17: 115–122. doi:10.5962/p.358950. S2CID 259715748 – via Biodiversity Library.

- 1 2 3 Norstog, Knut; Nicholls, Trevor J. (15 May 2019). The Biology of the Cycads. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501737329. ISBN 978-1-5017-3732-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Johnson, L.A.S. (29 July 1959). "The Families of Cycads and the Zamiaceae of Australia". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 84 (389): 64–117.

- ↑ Johnson, David, May 11- (2009). The geology of Australia (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-4619-3828-6. OCLC 856017224.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "Climate Warrumbungle National Park: Temperature, climate graph, Climate table for Warrumbungle National Park". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ↑ "Coonabarabran, NSW". Aussie Towns. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ "Coonabarabran climate, averages and extreme weather records - www.farmonlineweather.com.au". www.farmonlineweather.com.au. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ "Coonabarabran (Showgrounds) Monthly climate statistics". Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology, Australian Government. 27 May 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ "Macrozamia heteromera". Palm & Cycad Societies of Australia. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Castillo-Guevara, Citlalli; Rico-Gray, Victor (2007). "The Role of Macrozamin and Cycasin in Cycads (Cycadales) as Antiherbivore Defenses". Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society. 130 (3): 206. doi:10.2307/3557555. ISSN 1095-5674. JSTOR 3557555.

- 1 2 3 Whiting, Marjorie Grant (1963). "Toxicity of cycads". Economic Botany. 17 (4): 270–302. doi:10.1007/BF02860136. ISSN 0013-0001. S2CID 31799259.

- 1 2 Hall, J. A.; Walter, G. H. (1 August 2014). "Relative Seed and Fruit Toxicity of the Australian Cycads Macrozamia miquelii and Cycas ophiolitica: Further Evidence for a Megafaunal Seed Dispersal Syndrome in Cycads, and Its Possible Antiquity". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 40 (8): 860–868. doi:10.1007/s10886-014-0490-5. ISSN 1573-1561. PMID 25172315. S2CID 211490.

- ↑ New South Wales Ministry of Agriculture. Agricultural gazette of New South Wales. OCLC 780069290.

- 1 2 Asmussen, Brit (2012). "Aboriginal vernacular names of Australian cycads of Macrozamia, Bowenia and Lepidozamia spp.: a response to "Cycads in the vernacular: a compendium of local names"". Australian Aboriginal Studies (2): 54–71 1. ISSN 0729-4352.

External links

- "Macrozamia heteromera C.Moore". Atlas of Living Australia.