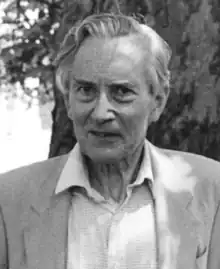

Sir Malcolm Pasley Bt, FBA | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 5 April 1926 Rajkot, India |

| Died | 4 March 2004 (aged 77) Oxford, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Oxford |

| Known for | Leading authority on German literature, particularly Kafka |

| Spouse | Virginia Killigrew née Wait (m. 1965) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Baronet Cross of Honour for Learning and the Arts (Austria) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | German literature and philology |

| Institutions | |

Sir John Malcolm Sabine Pasley, 5th Baronet, FBA (5 April 1926 – 4 March 2004), also known as Malcolm Pasley, was an eminent British philologist and literary scholar.

At University of Oxford, Pasley became the foremost authority of his generation on German literature, particularly well known for his dedication to and publication of the works of Franz Kafka.[1]

Biography

Early life

The only son of Sir Rodney Pasley, 4th Bt (1899–1982), and Aldyth née Hamber (1898–1983), he was born at Rajkot in British India, where his father was Vice-Principal of Rajkumar College, before becoming Headmaster of Barnstaple Grammar School (1936–43), then of Birmingham Central Grammar School (1943–59); his father edited the Private Sea Journals (publ. 1931)[2] of his senior lineal ancestor, Admiral Sir Thomas Pasley, who distinguished himself in the French Revolutionary Wars and was created a baronet in 1794.

Educated at Sherborne,[3] Pasley was commissioned in the Royal Navy, serving from 1944 until 1946.[4] He then went up to Trinity College, Oxford, where he read Modern Languages, graduating with a first-class degree in 1949 (BA, proceeding MA).

Academic career

Pursuing an academic career, Pasley was named Laming Travelling Fellow (1949/50) by The Queen's College, Oxford,[5] before appointment as a Lecturer at Oxford University in German. He taught at Brasenose and Magdalen from 1950 until 1958, when he was elected a Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford.

Fascinated by Franz Kafka and his works, Pasley rapidly became a leading figure in the editing of his texts. In 1961, charged with collecting Kafka's manuscripts from Zurich Cantonal Bank's vault, he carefully transported them by car from Switzerland to Oxford and deposited them with the Bodleian Library, which became the centre of textual scholarship on Kafka.[6]

Vice-President of Magdalen College for 1979/80,[7] Pasley was elected in 1983 to the Deutsche Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung, before retiring from academia in 1986.[8]

Honours and awards

National honours

Fellowships and academic awards

- 1983: Academician, German Academy for Language and Literature

- 1986: Hon. PhD, Giessen Univ.[9]

- 1988: Fellow, Institute of Linguists (FIL)

- 1991: Fellow, British Academy (FBA).[10]

Scope of his literary work

Pasley wrote about many German authors, with his initial studies of the German language, Nietzsche in particular, gaining him much fame. Pasley's work in this area was pioneering; his book Germany: A Companion to German Studies, first published in 1972, is still in heavy demand.[4]

Kafka

Pasley is best known for his scholarship of the Kafka writings. He began studying Kafka in the early part of his career and was introduced to Marianne Steiner, Kafka's niece and daughter of his sister Valli, by her son Michael, who was a student at Oxford. Through this friendship Pasley became the key adviser to Kafka's heirs. Pasley regarded Kafka as "a younger brother".[9]

In 1956, Salman Schocken and Max Brod placed Kafka's works in a Swiss bank vault due to concerns surrounding unrest in the Middle East and the safety of the manuscripts, which were with Brod in Tel Aviv. After significant negotiation, Pasley took personal possession of Kafka's works that were in Brod's possession. In 1961, Pasley transported them by car from Switzerland to Oxford. Pasley reflected on the adventure as one that "made his own hair stand on end".[4]

The papers, except The Trial, were deposited in Oxford's Bodleian Library. The Trial remained in the possession of Brod heiress Esther Hoffe, and in November 1988 the Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach purchased the manuscript for £1.1 million at an auction conducted by Sotheby's.[11][12]

At Oxford, Pasley headed a team of scholars (Gerhard Neumann, Jost Schillemeit,[13] and Jürgen Born) that recompiled the text, removed Max Brod's edits and changes, and began publishing the works in 1982. This team restored the original German text to its full (and in some cases incomplete) state, with special attention paid to the unique Kafka punctuation, considered to be critical to his style.[14]

Criticism of Pasley's work on Kafka

Subsequent to the publication of the Kafka works, Pasley began receiving criticism about the completeness of their German publication. To that end, Stroemfeld Verlag has requested permission to scan the manuscripts to produce a facsimile edition and CD-ROM. Aside from completeness, they cited a concern for the preservation of the works; some were written in pencil, and many were fading and crumbling.

Pasley refused their requests, joined by Marianne Steiner, who in 1998, told The Observer "I cannot forgive them for [the terrible things they had said about Pasley. I do not want them to have anything to do with the manuscripts."

In April 1998, Stroemfeld published a facsimile version of The Trial. This manuscript, being owned by the German government, was accessible to them. In this publication the manuscript and transcription are listed side by side.

Scholars in favour of the Stroemfeld editions comprise Jeremy Adler, professor of German at King's College London, American writers Louis Begley and Harold Bloom, professor of Humanities at Yale.[12]

Bibliography

Published works

- 1965 Kafka-Symposion, co-author with Klaus Wagenbach

- 1972 Germany: a companion to German studies (second edition, 1982) ISBN 0-416-33660-4

- 1978 Nietzsche: Imagery and Thought ISBN 0-520-03577-1

- 1982 Das Schloß (The Castle) ISBN 3-596-12444-1

- 1987/89 Max Brod, Franz Kafka: eine Freundschaft

- 1990 Der Prozeß (The Trial) ISBN 3-596-12443-3

- 1990 Reise-Tagebucher, Kafka's Travel Diaries

- 1991 Die Handschrift redet (The Manuscript Talks)

- 1991 The Great Wall of China and Other Stories

- 1992 The Transformation and Other Stories ISBN 0-14-018478-3

- 1993 Nachgelassene Schriften und Fragmente I

- 1995 Die Schrift ist unveränderlich (The Script is Unchangeable)

- 1996 Judgment & In the Penal Colony ISBN 0-14-600178-8.

Family

Pasley married, in 1965, Virginia née Wait (1937–2011), only daughter of Peter Lothian Killigrew Wait (1908–92), whose maternal grandfather was General Sir Lothian Nicholson.

Sir Malcolm and Lady Pasley had two sons:

Lady Pasley was a sister-in-law of the 9th Duke of Leinster (by the marriage of her brother, Mark Killigrew Wait, to Lady Rosemary FitzGerald).[16]

See also

References

- ↑ The Times.

- ↑ www.academic.oup.com

- ↑ "The Sherborne Register 1550–1950" (PDF). Old Shirbirnian Society. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 The Telegraph obituary

- ↑ www.queens.ox.ac.uk

- ↑ www.heraldscotland.com

- ↑ www.gazette.web.ox.ac.uk

- ↑ www.oxfordmail.co.uk

- 1 2 Jeremy Adler, Obituary The Independent (London), 26 March 2004

- ↑ www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk

- ↑ The Trial, Franz Kafka, Schocken Book, 1998, Publisher's Note page xiii

- 1 2 "Scholars squabble in Kafkaesque drama", Von David Harrison, The Observer, 17 May 1998, S. 23

- ↑ www.wikisource.org

- ↑ Jeremy Adler, "Stepping into Kafka’s head", TLS, 13 October 1995

- ↑ www.baronetage.org

- ↑ www.burkespeerage.com

Sources

- Reed, T. J. (2007). "Pasley, Malcolm" (PDF). Proceedings of the British Academy. Oxford University Press. 150: 148–158. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Reed, T. J. (8 January 2009). "Pasley, Sir (John) Malcolm Sabine, fifth Baronet". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/94106. Retrieved 30 January 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Sir Malcolm Pasley, Bt". The Times. 17 March 2004. p. 35.