_(cropped).jpg.webp)

American singer-songwriter Madonna (b. 1958) has had a social-cultural impact on the world through her recordings, attitude, clothing and lifestyle since her early career in the 1980s. Madonna has built a legacy that goes beyond music and has been studied by sociologists, historians and other social scientists.[1][2][3] This contributed to the rise of the Madonna studies, an academic and critical response dedicated to her work and persona for which Madonna's semiotic and image was diversified in a wide-ranging of theoretical stripe from feminism to queer studies among others.

Called a "major 'historical figure'" by academic Camille Paglia, Madonna attained the status of a "cultural icon" as was noted by cultural theorists or sociologists like Stuart Sim and Suzanna Danuta Walters. Frenchman scholar Georges-Claude Guilbert attributed her a greater cultural significance and proposed the singer as a postmodern myth. Madonna, which also gained a cult status amongst different audiences according to professor Sheila Jeffreys, has been called a Gesamtkunstwerk herself. Her critical reception, alongside her media coverage made Madonna one of the most "well-documented figures of the modern age". Both Madonna's references and impact are found —but not limited to— in the arts, literature, cinema, music and even science.

From a musical perspective and despite Madonna's music played a second place in scholarship analysis, she has been discussed with euphemism by multiple international authors as the "greatest" woman in music or arguably the most "influential" female artist in history. A large group of critics have retrospectively credited her presence, success and contributions with paving the way for female artists (as well she transcended gender) and changing the music scene for women in music —most notorious for dance and pop stages—with Billboard staff saying that "the history of pop music can essentially be divided into two eras: pre-Madonna and post-Madonna".[4] In terms of record sales, Madonna is regarded as the best-selling woman in music history recognized by Guinness World Records since the late 20th-century. She is often called an influence by other artists.

She is also a polarizing figure. During her career, Madonna has attracted contradictory social-cultural attention from family organizations, anti-porn feminists, radical terrorists and religious groups worldwide with boycott, censorship and protests. In the early-2010s, the Islamic state banned her name. Her critics and detractors attribute Madonna being a variety of things, such as being an important element in the normalization of prostitutions in the malestream culture. Author Shmuley Boteach blamed her to "destroy the female recording industry by erasing the line that separates music from pornography". In addition and mainly in the late 20th-century, she was negatively nicknamed a "modern Medusa" and some authors advised that she restored the image of the Whore of Babylon, for which she was described by some as "the most sexually perverse female of the twentieth century". Despite being a subject of contradictions, numerous academic studies have considered the way Madonna polarizes views and deemed her as a site of ambiguity and openness.

Cultural significance

Defining Madonna's career and reputation (beyond boundaries of music and popular culture)

The task of defining Madonna's social and cultural significance or impacted start by many authors tracing the boundaries she has crossed in both music and popular culture and became in a key aspect of who Madonna is to all others. Overall, her career as a whole has been defined with attaining an "unusual" or "extraterrestrial" status which she has also been suited as integral to the formation in understanding her. Newsweek contributor, Eve Watling feels that "Madonna seems to have done so much in her life that it's hard to grasp that she's a real person".[6] English music journalist, Paul Morley states what made her so ahead of her time, is that you can use her, colourise her, mix her, remix her, as part of your own narrative of meaning.[7]

As a woman performer, more than one author attributed her a "near-singularity position" and it was explained by scholars Katie Milestone and Anneke Meyer from Manchester Metropolitan University in Gender and Popular Culture (2013) when they wrote "she has been heralded as a 'unique female' figure because of the control that she exerts over her identity".[8] For American professor Arthur Asa Berger, "it is Madonna's power to create herself as a unique and distinctive icon that is so interesting".[9]

More comments defining her career, came from Caryn Ganz's The New York Times as she mentioned that Madonna has a "singular career" (in music, fashion, movies and beyond) that's crossed boundaries and obliterated the status quo.[10] Louis Virtel from Billboard argues that "the task of defining Madonna's impact is brutal" and viewed her career that amounts to "living mythology".[11] The same author, writing for Paper emphasized that "she graduated from pop hero to mythological wonder".[12] Singaporean magazine GameAxis Unwired explained that she pioneered a multifaceted career that "encompasses virtually every aspect of contemporary culture".[13]

To American writer Christopher Zara, Madonna symbolizes "one of those rare artists who forced the world to conform to her".[14] Another significance of her value and that a group of authors like writer Michael Levine and professor Thomas Ferraro have noted, is because Madonna has made a career of (virtual and literally)[lower-alpha 1] never doing the same thing twice.[16][17] At this point, British journalist Bidisha said that the singer has "no interest in nostalgia".[18] Matt Cain also shared similar thoughts praising her because she "never wanted to be seen as a nostalgia artist".[19] South African author Helen Nicholson commented in 2010: "None of her albums sound or look the same".[20]

Into the scope of Madonna as a musician, Gene N. Landrum, author of Profiles of Female Genius: Thirteen Creative Women who Changed the World (1994) wrote that "Madonna has been able to impact her industry as much as any woman in history".[21] At her profile in The 100 Most Influential Musicians of All Time (2009) by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., staff proclaimed she "achieve levels of power and control unprecedented for a woman in the entertainment industry".[22] Authors of 100 Entertainers Who Changed America (2013) explained that "her music alone cannot tell the full story of Madonna's colossal success and influence".[23]

In 1990, the arts-based BBC1 series Omnibus broadcast a profile on Madonna. Cultural critic Michael Ignatieff of BBC2's The Late Show criticized the broadcast, arguing that Madonna was not a serious artist and the program was "an amazing abdication of editorial integrity."[24] However, numerous authors have commented that Madonna "has transcended the role of being a musical artist", including American essayist Chuck Klosterman.[25] For Klosterman, "Madonna's status is no longer connected to music or sales".[25] Janice Min of Billboard declared that "Madonna is one of a miniscule [sic] number of super-artists whose influence and career transcended music".[1] In particular, American editor Annalee Newitz's thoughts were: "Madonna is not a musician. Certainly, she achieved fame within the music industry, but perhaps it might be more accurate to say that she began to be famous within the music industry".[2] As her music played a second place for many, mainly intellectuals who were more interested in discussing what Madonna means, American music critic Steven Hyden summarized:

[...] from the beginning of her career, Madonna has been primarily defined not by her music but by her ambition and her ability to present herself in visually interesting and ever-changing guises. There talking points have been repeated in pretty much every magazine profile ever written about her.[26]

Authors also discussed her position in popular culture and how she transcended it. For instance, back in the 1990s, Robert Christgau sees Madonna as a pop cultural symbol but discusses the idea that she transcends popular culture.[27] That idea was backed in the following decades (and perhaps before) by authors like Frenchman Georges-Claude Guilbert who says that long-time accepted as a pop icon, proposes the singer as a postmodern myth.[28] Also, Russell Iliffe from PRS for Music wrote that "during her career, Madonna has transcended the term 'pop star' to become a global cultural icon".[29] In 2015, an author from El Cultural wrote that she "surpasses the laws of physics, time, popular culture, and even metaphysics" as she become in a historical figure.[30] Others authors like academic Camille Paglia concurred that she is a "historical figure".[5]

General picture

The cultural meaning of Madonna, and her impact vary from author to author, but there is a universal agreement on that from an international view both 20th and 21st centuries. A common observation, Romanian professor Doru Pop at Babeș-Bolyai University confirmed in his book The Age of Promiscuity (2018) that "the cultural impact of Madonna was extensively analyzed by many authors".[31] That influence was described by Eve Watling of Newsweek whom expressed that "her enormous cultural impact seems Herculean" and concludes she defined the zeitgeist.[6]

Jock McGregor of Christian organization L'Abri concluded that "by looking at her life and what she symbolizes we can learn much about the values and weaknesses of our culture. We may even learn something about ourselves".[32] A similar suggestion was made in the late-2010s, by musicologist Eduardo Viñuela of University of Oviedo in conversation with Radio France Internationale (RFI) summarizing that "analyzing Madonna" is to delve into the evolution of many of the most relevant aspects of society in recent decades.[33]

In 2018, British sociologist Ellis Cashmore said that "we can feel the effect of the changes she triggered in our everyday life".[34] In 2009, art organization MiratecArts commented that "her influence is so powerful that it extends deep into the subconscious world of imagination, fantasy and dreams".[35] In this way, contemporary observers have compared Madonna to Lilith and reinforcing this view, authors of Mythic Astrology Applied: Personal Healing Through the Planets (2004) wrote: "Many men and women have reported Madonna appearing in their dreams. As she has become a living archetype in our culture, it is no wonder that this is so".[36] Kay Turner, an author turned-folklorist covered this area in her book I Dream of Madonna: Women's Dreams of the Goddess of Pop (1993) which is about the dreaming of 50 women on Madonna.[37] American journalist Ricardo Baca described that "to some, Madonna is a divine creation —an otherworldly gift to the masses in the form of an incessantly morphing entity".[38]

During part of her career, there was a general agreement that Madonna reflected society of her time. As professor John Izod of University of Stirling once said that she can be seen as a "hero of our times".[31] On top of this, American professor Marjorie Garber stated that "perhaps more than any other has read the temper of the times".[9] In similar vein, French editor Martine Trittoleno commented in 1993, that she is "more than a witness of the epoch, she is an active reflection of it".[39] Argentine essayist and writer, Rodrigo Fresán described her in 2000, as "the mirror of our days".[40]

In 1998, Madonna was suggested by Ann Powers of The New York Times as a "secular goddess, designated by her audience and pundits alike as the human face of social change".[41] Around this decade, Like Powers, some academics described her as "a barometer of culture that directs the attention to cultural shifts, struggles and changes".[42] British author George Pendle writing for Bidoun explained that she defined a way of living in the 1980s and 1990s and this led to her being consistently described as a "cultural icon".[43] Many years after, her status as a cultural icon is acknowledged in all press accounts according to authors of Ageing, Popular Culture and Contemporary Feminism (2014).[44] An author mentioned that "from day one, she was a full package of a way of living".[45] As Venezuelan writer, Boris Izaguirre commented that "there is a 'Madonna generation' of people who have grown up with her".[46] Prior years, in 2002, British academic researcher Brian McNair proposed that "Madonna more than made up for in iconic status and cultural influence".[47]

She's a major historical figure and when she passes, the retrospectives will loom larger and larger in history.

—Academic Camille Paglia on Madonna (2017) in a feminist perspective[5]

In his study on Madonna in the late-1980s, media scholar John Fiske concluded that "she is neither a text or a person, but a set of meaning in process".[48] Biographer Andy Koopmans observed the singer became in "a cultural obsession".[49] To professor Lisa N. Peñaloza, she is a "veritable cultural production industry".[50] As cultural critic Greil Marcus has it, "she is undeniably part of our culture".[51] Within the compendium The Madonna companion: two decades of commentary, American poet Jane Miller proposes that "Madonna functions as an archetype directly inside contemporary culture" and she compared her with the Black Virgin.[52] In the description of American author Strawberry Saroyan, Madonna is a "storyteller" and a "cultural pioneer". She stated: "Madonna's ability to take her message beyond music and impact women's lives has been her legacy".[53] Professors and authors of Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World, Volume 1 (2011), described:

Madonna's cultural influence has been profound and pervasive, as her multiple transformations and controversies have attracted the attention of numerous scholars working in a variety of fields, namely feminist and queer theory, cultural studies, film and media studies. Scholarly debates about Madonna encompass a broad of spectrum of topics ...[54]

William Langley from The Daily Telegraph feels that "Madonna has changed the world's social history, has done more things as more different people than anyone else is ever likely to".[55] Marissa G. Muller from W remarked that "Madonna has left her mark on every facet of culture".[56]

In the United States

Madonna has been called an "American icon". Both her early impact and legacy in the culture of United States have been noted either by Americans or international authors. Compared to others USA-symbols like Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, Barbie or Coca-Cola, academics in American Icons (2006) held that Madonna image "is immediately recognizable around the world and instantly communicates many of the values of U.S. culture".[57] On a broader scale, a gender consultant and musicologist in a course dedicated to the singer at the University of Oviedo in 2015, proposes that her history and evolution is "comparable" and can be "useful to analyze the historical development of the United States".[58]

In Fresán's view she is one of the "classic symbols of Made in USA".[59] Another external perception came from French academic Guilbert whose expressed in Madonna as a Postmodern Myth (2002) that "today, America knows more about Madonna than about any passage of the Bible".[28] Academics Johan Galtung and Daisaku Ikeda giving a perspective of the United States history commented: "US business and the hyper-successful US plebeian culture, outranking Christianity with its Penta-M: Mickey Mouse, Madonna, Michael (Jackson), McDonald's".[60]

Her main's impact in the national culture was made through the 20th century. Associate professor Beretta E. Smith-Shomade of Emory University felt that only Madonna rivaled the space Oprah Winfrey occupied in the late twentieth century and in the psyche of national culture.[61] In this period, she was constantly remarked by her sexual-feminist political movement. In the perspective of this American society from that era, Ann Powers said that "intellectuals described her as embodying sex, capitalism and celebrity itself".[41] The major role she served within these areas in her country, was summarized by literary academic, E. San Juan Jr. whom goes on to suggest that it may not be inappropriate to speculate, that U.S. "civilization" finds in the legendary "expenditures" of superstar Madonna Ciccone the erotic representation of Social Darwinism as the dominant national ethos.[62]

Retrospectively, Sara Marcus described with the height of her career, "the singer brought the changes to American culture". Marcus felt "her revelatory spreading of sexual liberation to Middle America, changed this country for the better. And that's not old news; we're still living it" and also ends saying that Madonna "remade American culture".[63]

Caroline von Lowtzow from German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung commented that she turned in the female incarnation of the American Dream of the "self-made man".[15] In this vein, U.S. cultural historian and author Jim Cullen wrote in 2001, that "few figures in American life have managed to exert as much control over their destinies as she has, and the fact that she has done so as a woman is all the more remarkable". Cullen also expressed "that Madonna has done this is indisputable".[64] At some point of her career, indeed, Madonna was climax of the itinerary of U.S. nationalism to a transnational according to E. San Juan Jr.[62] To professor Thomas Ferraro, "no one was more important to the culture as whole than Madonna" as he further expanded it: "Miracle worker and wonder woman, she was the faith healer of Ronald Reagan's divide and—conquer American, for its youth especially".[17] Professor Robert Miklitsch, said that she was "the perfect symbol for Reagan-era America".[65]

Scholar Frances Negrón-Muntaner examined that on a "global scale" Madonna embodied the freedom, in/morality, and material "excess" of (white) America.[66] Historian professor Glen Jeansonne gives his point saying that she "freed Americans from their inhibitions and made them feel good about having fun".[67] For Scottish author Andrew O'Hagan "Madonna is like a heroic opponent of cultural and political authoritarianism of the American "establishment".[68]

Modern culture (popular culture)

One of the great conundrums of the internet era is pop culture's short memory[...] But Madonna made real cultural change, and caused a few cultural crises, over and over again.

—Caryn Ganz of The New York Times on Madonna (2018)[10]

Of all the superstars who inhabit popular culture, Madonna (1958—) has attracted a volume of critical interest almost equal to the volume of recordings, videos and other materials she has sold. Madonna has remained an icon for postmodern theorist and popular audiences alike.[69]

— Glenn Ward. Discover Postmodernism: Flash (2011)

For some observers, she is more a pop icon rather than a musician, as critic Stephen Holden once pointed out: "Madonna is still much more significant as a pop culture symbol than as a songwriter or singer".[70] As was usual with Madonna, an array group of commentators have pondered her influence in popular culture. At first instance, professor Deborah Bell states that her impact "on pop culture is immeasurable".[71] In 2003, Harper's Bazaar held that "the ultimate pop-culture icon('s) ... influence is endless".[34] Historically, she is the first multimedia figure in popular culture according to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[72]

On a broader scale, her influence and contributions in the modern popular culture have been widely remarked by many. In 2019, The A.V. Club editors Alex McLevy and Kelsey J. Waite commented that as she "is modern pop's original icon" her influence will be "shared, enjoyed, and debated for decades to come".[73] In this vein, British sociologist Ellis Cashmore provided a justification saying that "even allowing for exaggeration, the point is that Madonna changed 'how the game works'".[34] Cashmore goes on to suggest even if she wasn't single-handedly responsible for moving the tectonic plates of popular culture, "there is a sense in which she was an archetype: others who aspired to become celebs were going to have to follow her example. Conspicuousness was everything".[74] Matt Cain is from the idea that "without her, from music to fashion to the whole concept of celebrity, today's pop culture landscape would simply not exist as it is".[75] Noah Robischon from Entertainment Weekly has concurred that she "has defined, transcended, and redefined pop culture".[76] American writer Gayl Jones even used the term "the Madonna culture".[77]

In multiple views and for decades, diverse international outlets have deemed Madonna as "the top figure" of popular culture or have given her an unusual status against almost any other entertainment figure. Across the 21st-century, those comments include the point of view of Belfast Telegraph columnist Gail Walker, whom compared her in 2008, to fellows or newer artists with saying that "she is from an entirely different universe", adding that "not even male icons have stayed at the front of popular culture the way she has".[45] In 2018, Rolling Stone staff remarked her "ability to stay at the center of pop culture for longer than nearly anyone".[78] In 2012, Latin critics like Víctor Lenore perceived the singer as the most influential presence of popular culture at that time.[79] In 2015, a scholar from program "Research in the Disciplines" of Rutgers University said that "Madonna has become the world's biggest and most socially significant pop icon, as well as the most controversial".[80] Commemorating her 60th birthday, The Guardian presented a series of articles discussing her figure in the point of views of multiple observers, including columnists and artists. In one of them, The Observer columnist Barbara Ellen called her the "pop's greatest survivor".[81] In 2015, Elysa Gardner of USA Today named her "our most durable pop star".[82] In summary, this continued perception was expressed by media consultants and authors of Media Studies: The Essential Resource (2013): "Madonna continues to be a challenging presence within popular culture".[83]

Musicianship

Her contributions to music have been appreciated by multiple critics, which have also been known to induce controversy. Madonna's music influence has been largely applauded. In summary and according to associate dean Jacqueline Edmondson, her continued importance radiates that "her legacy is important to understanding issues surrounding gender and the music industry in the twenty-first century".[84]

From a popular view, Madonna's voice talent has been famously denied. Another group of commentators, however, have praised Madonna's vocals and versatility in many ways. In this latter group, scholars Andy Bennett and Steve Waksman, in The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music (2014) agreed that "for pop singers in the style of Madonna, brilliant singing ability is not of utmost important" indeed, "the ordinariness of Madonna's vocal talent is key to her appeal".[85] Both Bennett and Waksman compared it to African-American artists of souls or R&B genres, "whose considerable vocal skill is a crucial aspect of their success".[85] They also extended the idea that by contrast, the fact that listeners can sing along to Madonna with ease, can hear themselves reflected in her voice, and can, perhaps, image themselves in her place, are all significant to her role as a pop star.[85]

In Settling the Pop Score: Pop Texts and Identity Politics (2017), professor Stan Hawkins wrote that "her musical texts should not be dismissed in view of their 'simplistic formulae'". He goes on to suggest that "at a general level, Madonna's sound points towards a specific historical moment in pop music, where representational strategies became exceptionally polyvalent".[86] Dr. Susan Hopkins has concurred that "Madonna's music is remembered not for its technical complexity but for the accompanying visuals".[87]

In 1986, Dr. Karl Podhoretz of the University of Dallas called her a "revolutionary voice who has altered the very meaning of sound in our time".[88] Three decades later, in 2018, Rolling Stone described the singer as "the most important female voice in the history of modern music".[89] Dutch linguist Theo van Leeuwen cited her as perhaps "the first singer who used quite different voices for different songs".[90]

Reputation

.jpg.webp)

Madonna attained an unusual status as a music performer and female singer. In 2021, Emirati editor Saeed Saeed from The National stated that "we do hold her to a higher standard" since "we are used to the 'Material Girl' dictating music trends for the best part of four decades".[91] He further notes that "Madonna's worst albums are considered a solid offering when compared to other artists".[91] In similar vein, Xavi Sancho from El País commented in 2014, that "the releases of this woman are not mere musical and commercial events", but rather exercises that marked the way forward and to certify the things.[92]

Historically, she is credited to popularize and being "the first" in numerous concepts within music industry. At first instance, and understanding these attributions, Madonna is commonly credited as the "first female" to have complete control of her music and image by a wide group of observers such as Roger Blackwell and Stephen Thomas Erlewine.[93][94][95][lower-alpha 2] In context, Ana Laglere, an editor of Batanga Media explained that before Madonna, record labels determined every step of artists but she introduced her style and conceptually directed every part of her career.[3] Associate professor Carol Benson and Allen Metz commented that the singer entered the music business with definite ideas about her image, but "it was her track record that enabled her to increase her level of creative control over her music".[98] Francesca Cavallo and Elena Favilli have also explained that in those days, "it was very rare for female artists to be the masters of their own destiny: they would let their male managers, producers, and agents make most of their decisions for them. Not Madonna".[99] Mary Cross pointed out that "she is not the product of some music industry idea, but her own woman".[100]

From a general picture, a vast group of international critics and media outlets have said that her presence is defined for "changing" or "revolutionize" contemporary music history for women's (and even regardless gender), mainly dance and pop scene.[101][102][103][104][105] Reviews beyond of gender perspective, includes Greek adjunct lecturer, Constantine Chatzipapatheodoridis who said that "Madonna's cultural impact helped shape the contemporary music stage, in terms of sound and image, performance, sex and fandom", as well reinvention.[106] Another consideration came from author Marshawn Evans, whose wrote in her book S.K.I.R.T.S in the Boardroom (2013) that Madonna "has also revolutionized how music is performed, delivered to the masses, purchased, packaged, downloaded, and even simulcast across a variety of cutting-edge platforms".[107] In 1984, Billboard commented that the simultaneous releases of LP, cassette and CD was pioneered with Madonna.[108]

.jpg.webp)

Like Evans and Chatzipapatheodoridis, others group of authors viewed how Madonna paved the way for pop releases. Thomas R. Harrison, an associate professor of music business and recording at Jacksonville University said that the singer changed the way pop artists were marketed.[109] Another supporter of this view was Erica Russell from MTV whose states that Madonna helped shape the way pop artists release music adding that "reignite interest in the art of the concept album within mainstream pop" after the decline of the rock-oriented concept album in the 1980s.[110] In another suggestion, Marissa Muller from W felt that she "normalized the idea that pop stars could and should write their own songs".[56]

Focusing the attention to women's music history and pop stage, her figure was summarized by authors of Ageing, Popular Culture and Contemporary Feminism (2014), arguing that she "is widely considered to have defined the discursive space for examining female popular music".[44] Another foundational example was included in Encyclopedia of American Social History (1993), as the authors agreed: "No singer better illustrates the new images of women in contemporary rock and pop than Madonna".[111]

It is not uncommon to read in the most prestigious media that she is the most influential woman in contemporary music.

—Announcer Juanma Ortega on Madonna (2020)[112]

Further commentaries, in these two scenarios of women's music and popular music, include Deutsche Welle staff, as they credited the singer as "the first woman to dominate the male world of pop".[113] British sociologist David Gauntlett, for example, cited a commentary from an author: "Madonna, whether you like her or not, started a revolution amongst women in music".[50] Joe Levy, Blender editor-in-chief makes a similar argument in discussing this, saying: She "opened the door for what women could achieve and were permitted to do".[93] Overall, in the perception of actress and activist, Susan Sarandon: "The history of women in popular music can, pretty much, be divided into before and after Madonna".[114] Billboard staff also recognized that "the history of pop music can essentially be divided into two eras: pre-Madonna and post-Madonna".[115]

She has been also discussed with euphemism by various international authors and media outlets as the "greatest" female artist or arguably the most "influential" woman in music history.[116][117][118][119] Ben Kelly writing for The Independent gave his thoughts on this saying that she has "ensured her legacy as the greatest female artist of all time".[118] Music outlets such as MTV or BET have deemed her as the most influential figure or woman in American music history as well.[120][121] Spanish cultural critic, Víctor Lenore named her as "the greatest female myth" in the history of popular music.[122]

Music videos and performances

Cultural and historically, her music videos concentrated much of her scrutiny in music terms, and she became "the most analyzed" figure from the rest of female music video performers.[124] Madonna is also cited by others as "the first female artist to exploit fully the potential of the music video", a statement included in her profile at Encyclopædia Britannica written by Lucy O'Brien.[125] The major role Madonna has played in the history of music videos, was commented by professor Norman Fairclough, whom suggested that "the evolution of the music video could indeed be studied through Madonna".[126] Film critic Armond White credited that she popularized the music video.[127] By some, the singer pioneered lipsynching and extensive choreography in the video format.[128]

The written about Madonna's performances are also large. From a popular view, music critic Michael Heatley held that she "had always set high standards with her stage shows".[129] While she wasn't the first performer in using wireless microphone headset in her concerts, author Drew Campbell called the "Madonna effect" to the "Madonna mic" that was bulky and black and high-tech, and "no one cared if it was visible".[130]

In terms of influence, multiple agents have credited to Madonna with "creating" the modern concert tour. One of these observers, William Baker mentioned that "the modern pop concert experience was created by Madonna really".[106] In other areas, she was credited by another group like scholars Berrin Yanıkkaya and Angelique Nairn, to paved the way of extravaganza in concerts as a theatrical spectacle in which the female music artist is placed centre stage.[123][75] If a specific title is mentioned, it is generally Blond Ambition World Tour. In this line, Jacob Bernstein of The New York Times cited previous examples like Donna Summer or Michael Jackson, but Madonna's 1990 tour "was bigger, bolder and more imaginative" for which she set the tone and the bar of modern megatours.[10]

Although Madonna is typically credited to set the template for stadium-sized spectacle according to BBC, she told the press in 2017, that wanted "to reinvent pop tours" exploring smaller-scale show and intimate shows in order to speak with the audience.[131] She explored this prior years with Madonna: Tears of a Clown,[131] and later with the all-theater tour Madame X Tour. For Stuart Lenig of Columbia State Community College, over the decades, "Madonna's carefully choreographed and performed shows became a gold standard of pop theatre, inspiring others to re-embrace the stage".[132]

Other critics noted that Madonna divided her performances into thematic categories and it was unusual for concerts during her time and from a creative level.[133] According to Baker, that split of sections derived that pretty much everyone copies or everyone is inspired by.[106] As stage performances seemed essential to developing her ever-changing personas and allowed her to create "exotic places" that she could control, Madonna told Rolling Stone in 1987: "I've always liked to have different characters that I project".[132] Unlike other performers, whom spend few weeks developing a show, Madonna has the budget to spend up to three months.[134]

Popularization of music things

In music terms, Madonna is credited to popularize various genres among other related music things. For example:

According to writer Arie Kaplan, Madonna is pioneer and popularized subgenre of dance-pop.[104] Music critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine said that she had a "huge role in popularizing dance music".[135] In another illustrative example, she has credit for the introduction of electronic music to the stage of popular music.[136] British sociologist David Gauntlett said that she introduced European electronic music into the mainstream of American pop culture.[50] According to the company The Vinyl Factory, her single "Vogue" popularized the usage of Korg M1.[137]

Musical

In September 2023, a jukebox musical based on the songs recorded by Madonna premiered in Balma in the southwestern of France. Titled Holidays, in reference to the singer's 1983 song "Holiday", the show mainly uses songs from her discography from the '80s and the '90s, and focuses on a group of four childhood friends who reunite as adults in the teenage bedroom where they spent every vacation together when they were younger. The show later transferred to the Alhambra in Paris at the end of the same month.[138][139]

Literature about Madonna

.jpg.webp)

At some point of her career, Madonna was heralded as the most talked about subject within female singers or celebrities either in terms of popular culture, music industry or academia. For instance, Andreas Häger from Åbo Akademi University cited that "hardly any other popular artist has received as much attention from the scientific community as Madonna".[140] Professor Imelda Whelehan of University of Western Australia provides a perspective that ran like this: "Is easy the most overdetermined figure. The most studied, critically acclaimed, derided and analysed of the performers".[44] Douglas Kellner proclaimed her as "the most discussed female singer in popular music".[141] On a broader scale, Madonna was described as "one of the most fascinating, uninhibited and well-documented figures of the modern age" in her profile at Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[72]

Authors have attempted to measure the literature on Madonna metaphorically. As media scholar David Tetzlaff equated reading it all to "mapping the vastness of the cosmos".[142] Indeed, Tetzlaff called her a "metatextual girl".[51] Rolling Stone also mentioned there is an "extraordinary amount of words written about her".[143] Robert Miklitsch, associate professor of Ohio University observed as well, there is an "extensive literature on Madonna".[65] Stephen Brown from University of Ulster commented that "the literature on Madonna is almost mind-boggling in its abundance".[144] According to American writer Alina Simone and author of Madonnaland (2016), encountered there is no dearth of material about Madonna, but an "overwhelming excess".[145] Guilbert compared that "it has become hard to open a book that has to do with U.S. popular culture without encountering some mention of Madonna".[51]

Authors on Madonna and terminology

Academics or pundits who specializes in Madonna (or her own academic branch: Madonna studies) have been called different ways. Authors from Henry Allen to Guilbert, used the name of "Madonnologists".[146][28] Others observers such as Anne Hull or Robert Christgau referred to the intellectuals working on Madonna as "Madonna scholars".[147][148] Same or different authors used several neologisms to describe commentaries about the singer. For instance, Christgau used the phrase "Madonnathink".[148]

Academics like Camille Paglia has been called a "Madonna enthusiast".[66] "Madonnaholics" was another tag.[144] Others were presented as "Madonna experts" in the popular press, like the case of Matthew Rettenmund in a Billboard article from 2015.[149] Another group of her pundits were called "Madonna historians", like Taraborelli did in his book Madonna: An Intimate Biography with Bruce Baron.[150]

Furthermore, Mark D. Hulsether cited in Religion and Popular Culture in America by Bruce Forbes, divided her critics and audiences into Madonna-hater (MH) and Madonna-lover (ML).[151] In the same way, some of her critics were called Madonnaphobes (or madonophobics) and Madonnophiles (or madonophilics);[152][51] both a blend words of Madonna and phobia and paraphilia, respectively.

Race politics

Cultural appropriation and multiculturalism

Another consideration focused in understanding Madonna's impact have been both her relationship or "appropriation" with diverse subcultures and group's imaginary adding a value in her contributions and work. In doing so, these things transcended her own figure and various studiers have found a significance. Many scholars focused their attention with a specific group or race; like bell hooks did with the black culture. In summary, the Madonna studies also provided a challenge views on racial perspectives.[154] Professor George J. Leonard, one of the contributors of The Italian American Heritage (1998) called her "the last ethnic and the first post-ethnic diva".[155]

Madonna indeed, deliberately cemented her popularity on ambiguity, thus appealing to not one but many social groups and subcultures.[126] As Matt Cain remarked that she "has always produced work that has brought marginalised groups to the fore", for instance, gay, Latino or black culture.[75] Author Shelleen Greene described "Madonna's racial tourism" and pointed out that for the millennial pop divas, anyone can have "blonde ambition" regardless of race.[156]

To Douglas Kellner, Madonna "helped bring marginal groups and concerns into the cultural mainstream".[141] An author said that "by making culture generally available, Madonna becomes the culture of all social classes".[157] Canadian professor Karlene Faith gave her point of view saying that Madonna's peculiarity is that "she has cruised so freely through so many cultural terrains" and she "has been a 'cult figure' within self-propelling subcultures just as she became a major".[158]

A concern derived from Madonna's ambivalent impact and position within these themes, is the academic interrogation that she has focused on her appropriations, subversions and transformations but her motivations in addressing cultural politics are uncertain to many.[50] At some point of her career, some have argued, for example that Madonna's insistence on solidarity with marginal groups and on moving between worlds was "duplicitous".[61] British professor Yvonne Tasker articulates her ambivalence, calling her an "interesting figure to the extent that her appropriation does at times work to question assumptions".[159] Taking her as a paragon, assistant professors Jennifer Esposito and Erica B. Edwards have commented that "pop stars today contend with this legacy and as a result take elements adding 'freshness' to their persona without dealing with the histories and realities the cultural imprints are born of".[160]

In addition, diverse examples have been documented in textbooks and other outlets her impact and footprints in some countries' culture, like La Nación, South China Morning Post and El País did with her history in Argentina, Hong Kong and Spain, respectively in terms of visits and collateral-relationship.[161][162][163] Madonna's mapping of the world cohabits with her singing in other languages. Partially or fully, aside of her native English, she also sung in Spanish ("Verás" or "Lo Que Siente La Mujer"), French ("La Vie en rose" or "Je t'aime... moi non plus"), Portuguese ("Faz Gostoso"), Sanskrit ("Shanti/Ashtangi") or Euskara ("Sagarra jo").

Black culture

According to a 1990 article of CineAction!, "Madonna's 'blackness' is a common, though poorly articulated theme of popular press literature".[165] As with other ethnics, Madonna commented about black culture, recalling that she wanted to be black as a child.[85]

Madonna is typically credited as the first to use black gay culture, in a clear and forward way.[160] Professor Ferraro studied her relationship with black culture, saying that "no white pop star (in the 1980s and 1990s) ever owes more to black male productions, to black-style dance and stage presentation, including Reggie Lucas, Nile Rogers, and Stephen Bray, than Madonna". Ferraro also states that "no diva has spent more time on camera and off with men of color, professionally and romantically involved" and ends describing her as "the most accomplished Italian-to-black crossover artist in history".[17]

However, she has faced criticism in her usage of black sub-culture themes and was viewed by some as a white privilege. Barbadian-British historian Andrea Stuart found that she "deliberately affected black style to attract a wider audience".[166] American historian David Roediger noticed bell hooks' criticism (a famous Madonna detractor), that for her "the image Madonna most exploits is that of the quintessential 'white girl'. To maintain that image she must always position herself as an outsider in relation to black culture".[167] Art historian John A. Walker, also observed criticism from hooks, and concluded that this caused many women of colour to dislike Madonna.[164]

American culture and Italianness (Italian-American identity)

.jpg.webp)

Authors remarked her background as an Italian-American and she identified herself as such. Fosca D'Acierno wrote in The Italian American Heritage (1998) that "so much has been written about Madonna, but rather little has been about" singer's "Italianness".[168] Other group of authors suggested that she "has traded on ethnicities other than her own (Italian American)".[165]

Particularly, D'Acierno studied at that time how she became a vehicle for the expression of many of the qualities that are exclusive not only to Italians but for Italian American women.[168] Professor Thomas Ferraro also studied her "Italianness" praising her because "never stops talking about her background",[17] although all of them remarked that she does not affirm her cultural background and identity singing in Italian.[168][155][17] At other point, the singer has been described as one of the Italian American performers that played a "definitive role" in the musical culture.[155]

Musically speaking, various critics agree that Madonna, rather than export US music, has imported new (mostly European danceclub) trends into the United States.[126] In terms of iconography, US culture does not seem to have played a central role in her work either, according to José Igor Prieto-Arranz from University of the Balearic Islands.[126] For example, she rarely wrapped herself (metaphorically or literally) in the American flag, but has often adopted other flags of convenience.[50]

Asian and other cultures

Mostly in her 1992–1993 and 1998–2001 periods, Madonna also adopted, modified, subverted and deconstructed Asian (specially Thai, Hindu and Japanese) elements and imagery.[126] She also replicated the practice of hiring Asian and African American backup singers and dancers.[169]

Like with other races, Madonna's reception with Asians and Asian Americans have been also studied in surveys. An example occurred with scholars Thomas K. Nakayama and Lisa N. Peñaloza, and most of them, according to their study felt "alienated by the visual narratives of her early videos, and clearly distanced themselves from politics of the visual texts".[50] Other observers also noticed the influence of England heritage in her work, as she was married to Guy Ritchie and lived in the United Kingdom for years. However, Madonna's exploration of intra-Caucasian identities has received little academic attention.[50]

Latino and Spanish culture

She has also had a strong relationship with the Latin culture, as Jorge Becerra from LatinAmerican Post says.[170] Professor Santiago Fouz-Hernández in his book Madonna's Drowned Worlds states that the Hispanic culture "is perhaps the most influential and revisited 'ethnic' style in her work".[126] Another example is her personal life, including relationships like with Carlos Leon to whom she gave birth to Lourdes "Lola" Maria Ciccone Leon.[50] In many ways, she was viewed as a precursor of the Latino boom-way started in the 1990s, with early works such as "La Isla Bonita",[50][171] and that other American pop singers such Jennifer Lopez, Beyonce or Christina Aguilera have replicated.[171]

Frances Negrón-Muntaner discussed in Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture (2004) Madonna's impact in the Latin culture of the United States and mainly, Puerto Ricans during the 1980s and through the 1990s. Equally important, author suggested that "Madonna's nod created the illusion of insider status for Latinos of all sexualities in U.S. culture". As Thomas K. Nakayama and Lisa N. Peñaloza found: "Latinos tended to respond to Madonna texts in a way that underscored their specific cultural literacy".[66]

Focused the attention to Puerto Ricans, Negrón-Muntaner describes the singer as the one who "came to most successfully commodify boricua cultural practices for all to see".[66] She was also described by the same author as the first "white pop star to make boricuas the overt object of her affections" and this "produced a queer juncture for Puerto Ricans representation in popular culture" and in "romancing Latinos in this specific way, Madonna made boricua men desirable to an unprecedented degree in (and through) mass culture.[66]

Like Negrón-Muntaner, other writers closely examined her impact in Puerto Rico, including Carmen R. Lugo-Lugo whose article The Madonna Experience (2001) for the feminist academic journal Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, explored the "political aspect of the Madonna phenomenon in Puerto Rico by looking at her and her status as a public figure", as well Madonna's impact in the Puerto Rican young girl culture of the 1980s.[172]

The incident with the Puerto Rican flag during her concert in the island as part of The Girlie Show in 1993, was also cited by various authors, with Carlos Pabón calling it in his essay De Albizu a Madonna: Para armar y desarmar la nacionalidad (2003) as "a story that has no parallel in the imaginary of the country".[173] In Argentina, another Latin country, Madonna's relationship was briefly divided after her film of Evita, with criticism mainly from the Federal Peronism.[161]

Commercial influence

.jpg.webp)

Madonna's semiotic and influence also extended to business schools sphere and marketing community. More than one economist, marketer, entrepreneur or other business expert made analysis or dedicated courses studying her continued "success" and commercial "strategies" with academic Douglas Kellner saying that "one cannot fully grasp the Madonna phenomenon without analyzing her marketing strategies", tactics that have been "essential" to her success.[175][141] In Understanding Popular Music, New Zealand professor Roy Shuker wrote that "the continued success of Madonna provides a fascinating case study of the nature of star appeal in popular music".[176] At this point, writer Andrew Morton has concurred that "her success has certainly impressed the business community and senior professors at Harvard Business School beat a path to her door".[177]

Kelley School of Business commented that "she is someone everyone can learn from, though the lessons run counter to conventional marketing wisdom of the 4Ps variet".[178] Economist and scholar Robert M. Grant dedicated a class on her in 2008 highlighting the context of "intensely competitive" and "volatile world of entertainment".[179] Marketer expert and professor Stephen Brown from University of Ulster named her a "marketing genius" while studied her case.[144] In addition, Martin Kupp and Jamie Anderson in a study dedicated to her in London Business School, concluded that she "is a born entrepreneur".[180] In 2013, athlete turned science writer, Christopher Bergland wrote in Psychology Today an article analyzing her enduring success from the perspective of neuroscience.[181]

Others created new phrases or terms using Madonna as a quintessential for business. For instance, business professor Oren Harari coined the expression "Madonna effect" inspired in her business tactics and changes while deems its use for both individuals and organizations.[182] Doctor Peter van Ham writing for NATO Review explained the "Madonna-curve", an expression used by some business analysts to describe the "adapting to new tasks whilst staying true to one's own principles". He further explained that "businesses use Madonna as a role model of self-reinvention".[183]

Success and longevity

.jpg.webp)

The terms "success" and "longevity" has been scrutinized in Madonna's case by multiple agents and how this shaped the views beyond her own figure. Thales de Menezes from Brazilian newspaper Folha de S.Paulo commented in 1999, that she is "rare case of a lasting relationship with success".[184] Others commentatros have described both her longevity and success as "unparalleled", like David Thomas from MTV Australia in 2013.[185]

Some observers start remarking Madonna's beginnings when critics like Robert Hilburn were already "predicting" her rapid decline.[150] Others compared her to new debutants like Billboard magazine editor, Paul Grein did with Cyndi Lauper; the singer to whom she was first compared and Madonna was viewed "somewhat less talented than" her.[52] Grein said: "Cyndi Lauper will be around for a long time; Madonna will be out of the business in six months".[150] Shuker commented that "Madonna's critical status has moved beyond the earlier negative views".[176] In short, Madonna later "set a template" of longevity and enduring success as was suggested by more than one author. In a bigger proportion, and more than anyone else, she ended "embodie[d] female success in a male-dominated industry".[50]

The longevity attached to Madonna can be traced back to at least 1991, or in other words, before having a 10-year-old career. At that time, outlets started to describe her career from "veteran" to have the "equivalent to five lifetimes in rock-star years".[186][187][188] Diverse outlets in many parts of the world, provided contemporary views, like Australian newspaper The Canberra Times in 1992, whom staff attributed her ability to change her image frequently as the "secret of Madonna's longevity".[189] In 1994, author Gene N. Landrum described her success at that time in the following way: "Her success has made her the most visible show business personality of the era, and arguably of the century".[21] As she accumulated success in many ways in her next decades, British sociologist David Gauntlett said that the singer has provided a recipe for "longevity", which many artists, female and male, may try to emulate.[50]

At some point of her career, many of her "scandals" or works were predicted to be the "end of her career" because she "gone too far", like when she published her first book Sex accompanied of the album Erotica and the NC-17 movie, Body of Evidence. It was around this time, in 1993, media scholar David Tetzlaff observed that singularity: "Never before has a popular performer survived so much hype for so long and continued to attract the fascination of a broad public while staying completely contemporary".[50] Tetzlaff goes on to suggests: "The cultural longevity of Liz Taylor or even Elvis Presley has been largely based in nostalgia [...] and others have been around "forever" but have only occasionally, if ever, been associated with the level of publicity that constantly envelops Madonna". By this point, Tetzlaff mentioned The Beatles as an only comparable example to Madonna's case.[48] Virtually over the decades, similar views were suggested by commentators like Jennifer Egan (2002) and LZ Granderson (2012).[190][191] In 2018, many years after Tetzlaff's claims, Cashmore held that she both epitomized and helped usher in an age in which the epithets "shocking", "disgusting" or "filthy" didn't presage the end of a career.[34] Professor Robert Miklitsch noted that she responded with her 1995 song "Human Nature" to her critics about her longevity with the phrase "Did I stay too long?"[65]

In an industry where some artists don't last longer than a packet of chewing gum, Madonna has built a career of success and longevity that is unparalleled.

—David Thomas from MTV Australia on Madonna in 2013[185]

As she turned older, perception have been ambivalent towards Madonna's longevity and success, but mainly contrasted because her long-position as usually a "top artist". In 2020, author Bobby Borg suggested, for example, "no matter which period of her career you examine, Madonna has remained one step ahead of the pop competition and at the forefront of the music and fashion".[192] Contrary, in Fresán's view: "As far as I'm concerned, Madonna now lives off the shock wave of a Big Bang that has already passed and gives off the visible but distant light of a dead star. A dead star but, yes, very intelligent".[193] Deborah Jermyn from University of Roehampton provides an explanation saying that her "frequency is generally steady until key moments in her career produce intense spikes of activity".[194]

In general, Guinness World Records have referred to her as "the most successful female artist" in both 20th and 21st centuries.[195] The same or similar description has been used in academic fields. A summary of this point was provided by scholars writing for Journal of Business Research in 2020, Canavan Brendan and Claire McCamley when they concluded that "she's probably the most successful female music artist ever in terms of her record sales, tour receipts, brand recognition and longevity".[196] British musicologist David Nicholls also suggested: "Madonna became the most successful woman in music history by skillfully evoking, inflecting, and exploiting the tensions implicit in a variety of stereotypes and images of women".[197] In 2015, gender consultant and musicologist Laura Viñuela taught at University of Oviedo that "is the only woman who has such a long and massively successful career in the world of music".[58]

Through the years, another group of authors used superlatives to refer her status, success or impact in the field of music industry. Biographer Chris Dicker summarized that it has been said that she is "the most successful woman in the history of the music business".[198] Following Dicker's summary, outlets like Deutsche Welle called her "music business' most successful woman".[113] Another similar description was used by David Horowitz and professor Peter N. Carroll, as they deemed her "the most financially successful female entertainer in history".[199]

As a businesswoman

She also received appreciation from a varied of industry experts in her role as a businesswoman and once was named "America's smartest businesswoman".[201] That treatment was then unusual for a female singer. Gene N. Landrum (1994) commented, "Madonna's business acumen and entrepreneurial talent were becoming legend when such bastions of male capitalism as Forbes" named her as such.[21] Around this time, she was one of the few female CEOs in the industry.[202]

By this time, Madonna's business tactics were distinctly different from other artists as she was reported to endorse products she thinks will enhance her, more than the product.[189] According to biographer Adam Sexton, she was praised by people who work with her as they "agree that she is a rarity among entertainers, who runs her own business affairs".[70] One of these observers, Jeffrey Katzenberg then chairman of Disney Studios, described: "She has a very strong hand in deal-making and financing of her enterprises. Nothing gets done without her participation".[70]

For many of these observers, Madonna transcended her roles of musician and pop icon in becoming a businesswoman. At first instance, Jennifer Egan noticed that a "popular answer" among critics, "she's done (all about her life and work) it through sheer business savvy".[190] In this vein, her business profile quickly became in a signature for her career, while commentators used numerous adjectives to remark that status. Authority sources like Kelley School of Business, for example, said that she is more than a "pop cult icon" and has been "an empire from day one".[178] Professor Robert Miklitsch described that "[she] is herself a corporation and a rather diverse one at that" in his book From Hegel to Madonna (1998).[65] American author Kevin Sessums used a similar description calling her "a corporation in the form of flesh".[48] Colin Barrow a visiting scholar at the Cranfield School of Management viewed her as "an organisation unto herself".[201] New Zealand professor Roy Shuker agreed and said that she "must be viewed as much as an economic entity as she is a cultural phenomenon" adding that she "represents a bankable image".[203] Kellner also viewed her as "one of the greatest PR machines in history".[141]

Overall, her contributions in helping "to shape" music businesses was appreciated by Lucy O'Brien whose said that she became the first one "to exploit the idea" of pop artist as a brand in the 1980s.[204] Editor Gerald Marzorati proposes that "Madonna's contribution has been to usher in the phenomenon of star as multimedia impresario".[190] David Bruenger from Ohio State University observed Madonna's economic impact and wrote in Making Money, Making Music: History and Core Concepts (2016) that "she pioneered [various] brand management strategies".[205] In Bitch She's Madonna (2018) authors go beyond previous descriptions, saying that "the music business, as we have seen it grow, is what it is largely because of her, her ambition, her vision and her perfectionism, along with her undeniable musical and entrepreneurial power and talent.[171]

Brand

.png.webp)

In terms of branding, experts have attributed to Madonna a particular position. South African author Helen Nicholson, goes to suggest Madonna is the "Queen of Branding".[20] From an overview perspective, New Zealand academic Warwick Murray among others have called her a "global brand".[206] To some, she is "a quintessential brand".[207]

Madonna is perhaps the epitome of celebrity marketing and celebrity branding, according to Jim Joseph, author of The Experience Effect (2010).[207] Public relations expert Michael Levine reviewed her then 20-years-old career in A Branded World (2003) praising her beyond any other artist as the most successful act in establishing and maintaining a brand. Levine also said: "Establishing herself as something different right from the start, [she] has bucked every trend and every rule of Branding and still managed to become the most well-known, well considered brand in the entertainment business".[16]

Another consideration came from marketing executive Sergio Zyman whom stated that "unlike almost anyone else in her business, has an uncanny ability to retool the Madonna brand". Zyman also believes that "no one repositions herself as well —or as frequently— as Madonna".[208] From a cultural perspective, Timothi Jane Graham of American business magazine Success commented that Madonna's brand has been a "mirror of our own journey through pop culture and as a people" with her transformation.[209] American business magazine, Fast Company discussed her in a 2015 article as "the biggest pop brand on the planet".[210]

Financial accomplishments

Another group of authors whom pondered her cultural significance, have reviewed her role as a boss and business accomplishments noting the impact this have had in her career and beyond Madonna's own figure. Clifford Thompson, author of Contemporary World Musicians (2020) wrote that she "has been overwhelmingly successful on a financial level".[211] As she was described itself a product, the singer was called an "economic phenomenon".[212] Authors of the academic compendium The Madonna Connection (1993) wrote that she became herself a "valuable property in the world of international capital".[48] Newspaper ABC named her in 1992, as the "most prolific, profitable and universal consumer object since the commercialization of Coca-Cola".[213] Another author deemed the singer as "her own entertainment industry".[87]

Commercially, Madonna generated sales for Warner Bros. of over $1.2 billion in the first decade of her career (c. 1983–1993).[214] She also added hundreds of millions more for other companies.[70] Total lifetime worldwide sales for Madonna's CD's and other music products were at least $2 billion as of 2003, according to her publicist Liz Rosenberg.[25] According to an investigation by Judson Rosebush, Madonna accounted for something like 20 to 33 percent of all record sales from Warner Communications, or over $200 million and she even affected the stock.[215] In fact, author Robert Burnett reported that Time Warner "usually feature[d] Madonna's picture prominently in its annual report".[216] In the 1990s, a group of authors like academic Roy Shuker deemed the singer as arguably "Time Warner's most effective corporate symbol".[65] Others commented that "the real value that Madonna has to offer a multinational conglomerate cannot be calculated in sales figures alone".[48]

A contract she signed with Time Warner in 1992, made her then highest-paid female entertainer in history.[211] Under this agreement, she founded the entertainment company Maverick which included the record label, Maverick Records. It was recognized by Spin as the most successful "vanity label" and while under Madonna's control it generated well over $1 billion for Warner Bros. Records, more money than any other recording artist's record label at that time.[217]

According to Taraborrelli, the existence of Maverick Records was "anomaly" as she became in one of the first female artists to have a "real label", and one of the few women to run her own entertainment company.[150] During her time with this conglomerate, she attained "significant patronage". At any rate, she helped Asians or Europeans to become famous in the U.S, as she made it possible for the Chinese film Farewell, My Concubine to reach a relatively large American public.[28]

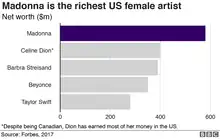

In addition, she has been included in several Forbes lists since the 1980s and once named the richest woman in music. Thompson noticed that "for several years running, she was listed in Forbes as one of the 10 highest-paid entertainers".[211]

Publicity and advertisements

Madonna has also made an impact in the world of advertisements and publicity in many ways, including cultural and commercial perspectives. Christopher John Farley commented that her career has "never really been about music", but about other stuffs like publicity.[218] A similar description was used by authors of Challenging Theory (1999): "Madonna's success is founded not on her lyrical art or musical talent but on her skill as self-publicist".[219] Martin Amis described something that was a constant by some point of her career, as he saw that "her publicity gets publicity".[32]

Sociologist Cashmore, praised her influence in this area saying that "Madonna was the first celebrity to render her manufacture completely transparent". He further explained that "unabashed about revealing to her fandom evidence of the elaborate and monstrously expensive publicity and marketing that went into [her work], and indeed, herself, Madonna laid open her promotional props".[74] In 1992, American journalist Michael Gross presenting her as "the world's most advanced human publicity-seeking missile".[220]

Madonna's debut occurred at the same time the relationship with music and advertisings marked a "new era", including the association with music videos and the MTV generation.[171][221] By that time, critics like Simon Frith, however, noticed that for years she refused to do an ad.[222] For instance, her first nationwide advertisement was until her contribution on the first Rock the Vote campaign in 1990.[50]

Her first major advertisement debut was in Japan, with a Mitsubishi Electric campaign in 1987 to promote a videocassette recorder (VCR). Her collaboration doubled company's share of the domestic VCR market to 13%,[223] and erased the corporation's image of being "safe but bland" as researchers found that most Japanese no longer considered Mitsubishi Electric a conservative company.[223] Beyond her impact in Mitsubishi, Madonna campaign led to Japanese agencies and advertisers to feature musicians in advertising, again invigorating the overall interest in using foreign celebrities in advertising.[223] Since that time, many foreign artists have appeared in Japanese TV commercials.[223]

She made her Western advertising debut with "Make a Wish" for Pepsi in 1989. In a single night, an estimated 300 million people from 40 countries viewed the commercial.[171][224][lower-alpha 4] The event constituted the single largest one-day media buy in the history of advertising.[224] Similar to a jingle the video was accompanied with the song "Like a Prayer", marking the first time that a videoclip was planned as an advertisement.[171] The significance of Pepsi-Madonna cross-promotional collaboration has been studied by numerous observers, either for Pepsi advertising, the Cola wars,[225] and Madonna's business acumen. For J. Randy Taraborrelli, these events surrounding Madonna-Pepsi partnership, "turned out to be one of the biggest controversies in the history of corporate advertising's often uneasy liaison with pop music".[150] Status for both company and Madonna were typified at this time, as one of the largest companies part of Fortune 500, and she as the "most famous woman" on the world,[224] or "world's biggest pop star".[150] In both side, ambition were enormous, as the company planned "to change the way popular tunes from major artists are released in the future",[222] and the way Madonna was in charge of every detail; for instance, she refused to hold a Pepsi can in the commercial.[150]

After her Pepsi commercial, for authors of Bitch She's Madonna (2018) she was a pioneer of creating musicality.[171] Spanish cultural critic Víctor Lenore states that with this ad, she "opened the door to major endorsements of fashionable singers and multiplied the global impact of pop music".[122] To Taraborrelli, none of the future Pepsi ads "would generate the excitement of Pepsi's failed deal with Madonna".[150] Phil Dusenberry, however, said that one of the biggest two regrets of his career was casting Madonna for Pepsi.[226]

Cultural and commercial trends

In most part of her career, the relationship with Madonna and trends attracted commentaries from multiple observers, as Canadian author Ken McLeod confirmed that "she has played a part in several cultural trends".[227] Art historian John A. Walker deemed her as an "acute observer of trends" in terrains from art to film.[228] José Igor Prieto-Arranz from University of the Balearic Islands called her a "cultural product" itself and agent of cultural production.[126] In this vein, professor Suzanna Danuta Walters commented that in academic writing, she was "understood" as a personification of commodity capitalism and for her capacity to "make human beings into objects for sale and circulation".[229]

The rhetoric view in most part of her career, was that she usually "sets trends",[230] with a general perception (during decades) that she was slightly "ahead of the curve".[209] In this journey, she received the tag of being a "coolhunting". Scientist Jamie Anderson, one of the authors of The Fine Art of Success (2011), commented that she "is one of the world's first artists to bring this approach to the music industry".[231] Historically and long before this term (coolhunting) entered in the mainstream marketing discourse, American author Rob Walker commented that she was "renowned for spotting new trends".[232] On top with this, writer Popy Belasco virtually called the singer as the "first coolhunter in history".[233] According to David Graham from Toronto Star, "Madonna's knack for cool hunting is legendary".[234] During the height of her career in the 21st century, MuchMusic deemed the singer as "the world's top trend-maker" (c. 2006).[235]

Criticism came from observers like lecturer Susan Hopkins from University of Southern Queensland, whom said that Madonna "pioneered a lot of cultural trends that didn't do average working women a lot of favour".[236] Timothi Jane Graham from American business magazine Success even said that "it was once rumored she actually paid cultural sleuths to keep her informed of every shift and modulation of the current trends before they made their way into the masses".[209] After the release of her album Hard Candy many observers called that she followed trends, instead created them.[230]

List of fad and trends "credited" to Madonna

- Nota bene: This section only includes illustrative examples. Other examples can be found in other sections of this article.

As Madonna has been reported or cited as a help or motivation for the rise, introduction or popularity of several things such as terms, places, cultural practices, fashion trends or products. Some illustrative credits of these fad and trends started or forwarded by the singer (or almost mostly by her), includes:

Within sector of tourism, Manuel Heredia, minister of tourism in Belize, discussed with El Heraldo de México how "La Isla Bonita" has helped to attract tourists to the San Pedro Town.[237] A similar example occurred when she moved to Lisbon around 2017, and Portuguese or Spanish outlets credited her presence as a boost and help for the tourism industry within sectors such as "luxury tourism" or real estate business.[238][239]

.jpg.webp)

She played a major role in some ancient cultural practices to normalize them in the modern Western society. Numerous sources such as The Independent credited Madonna to popularise the Jewish mysticism in the Western world.[240] American novelist and former educator Alison Strobel commented that "Madonna had popularized it to the point where it was simple to find a place to go learn".[241] Her figure has been also important to the role for the Kabbalah in Occident; media analyst Mark Dice called her the "celebrity face" of this discipline.[242] In 2002, author Eric Michael Mazur wrote that "she has almost single-handedly made American teenagers vaguely familiar with Hindu mantras and Jewish kabbalistic".[243] The New York Times (NYT) contributors concluded she "brought" yoga to the masses.[10] The same perception of NYT is shared by others, while professors Isabel Dyck and Pamela Moss particularly credited her the popularity of Ashtanga Yoga.[244]

In idiomatic expressions, associate professor Diane Pecknold in American Icons (2006) noticed that she helped to popularize words and phrases in the English lexicon. Pecknold included the term "wannabe" used by Time magazine back in 1985 to describe the Madonna wannabe phenomenon. Another inclusion was the title of her first feature film Desperately Seeking Susan which produced a new idiomatic phrase considering the newspaper headlines.[142] Her position in the raise of idiomatic term fauxmosexual was noted by Kristin Lieb of BuzzFeed News whose remarked in 2018 that this phenomenon started with her kissing both Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera at the 2003 MTV Video Music Awards.[245] The "Madonna-Britney influence" in this term was early mentioned by MedicineNet in 2004.[246] People staff agreed that she "coined" the term for "Get rid of it".[247]

The association with Madonna helped other businesses or people. The Madonna-Marilyn Monroe connection has been extensively discussed and largely thanks to Madonna, Monroe has become "the woman who will not die", as Gloria Steinem puts it, "an ever-present fixture in everyday American culture".[248] The Daily Telegraph explained that the singer helped transform Frida Kahlo into a collector's darling.[249] Another supporter of this view, is art historian John A. Walker whom said that partly due to Madonna, the artist became a posthumous celebrity not only in the domain of art history but also in popular culture.[164] Mexican art magazine Artes de México staff notated in 1991, the importance of the singer for the "Fridomania".[250] Author Juliana Tzvetkova wrote that Dolce & Gabbana "received their first international recognition thanks" to Madonna,[251] while journalists like Lynn Hirschberg notated that the attention around fashion designer Olivier Theyskens was "intensified thanks to the singer".[252] A similar situation occurred with Jean-Paul Gaultier as many people are familiar with his work via his collaboration with the singer.[251]

Madonna's visibility in fashion also set numerous fads. But from a cultural sense, scholars Rhonda Hammer and Douglas Kellner felt that the phenomenon of femininity inspired by South Asia as a tendency in Western media could go back to February 1998 when Madonna released her video for "Frozen". They wrote that "although Madonna did not initiate the Indian fashion accessories beauty ... she did propel it into the public eye by attracting the attention of the worldwide media".[253] Professors Christopher Partridge and Marcus Moberg have commented: "Since Madonna first put Indian cultural symbols on the global fashion map, henna, bindis and Indian sartorial designs have become part of the global popular culture reinforced by Bollywood's Western invasion".[254] Authors go to further suggest that she ensured the Hindu invasion of Western popular musical space and made South Asian popular culture globally visible.[254]

She was also suggested in popularize cultural appropriation by a Newsweek contributor.[6] Madonna also was credited to take Goth fashion from underground to mainstream.[234] She has carried the burlesque to mass culture according to Latin critics.[79] In many ways, her documentary Madonna: Truth or Dare is viewed as a precursor of the TV reality concept.[75]

Mass media responses and reception

Rather than a singer, she is a global multimedia phenomenon in the perception of José Igor Prieto-Arranz from University of the Balearic Islands.[126] For Tim Delaney, author of Connecting Sociology to Our Lives: An Introduction to Sociology (2015), "her perceived outrageous behavior in the 1980s and 1990s set the tone for public discourse and analysis".[255] Professor Ann Cvetkovich remarked that figures such as Madonna, reveals the "global reach of media culture".[256] In another consideration, British sociologist Ellis Cashmore proposed that more than anyone else, Madonna effected a change in style and the manner in which stars engaged with the media.[34]

Madonna's public and media appearances, has generated a vast scholarly analysis. Authors in academic compendium The Madonna Connection (1993) confirmed this saying that "other scholars analyze media-Madonna discourses and representations".[48] In the late-1980s, John Fiske, a media scholar and cultural theorist perceived her as a "site of meanings" for performance purposes,[31] adding that "she is a rich terrain to explore".[257] Various academics also noted a commentary from The Village Voice editor Steven Anderson on Madonna, whose said in 1989: "She's become a repository for all our ideas about fame, money, sex, feminism, pop culture, even death". In a retroactively view of this point, British reader Deborah Jermyn of Roehampton University commented in her book Female Celebrity and Ageing (2016) that Madonna "does age and rather than retire from view Madonna continues to function as a repository".[194]

A scholar once points that because she has come to occupy such a large portion of public media attention, "Madonna functions rather like what environmentalist call a megafauna".[258] In the perception of Spanish philosopher Ana Marta González, Madonna doesn't have a "cultural" prominence but proposes in her 2009 essay (Ficción e identidad. Ensayos de cultura postmoderna) that with her media appearances the singer "would be more culturally significant than most of the people who have changed the course of history".[259] Media scholar David Tetzlaff said that her "omnipresent" appeal "has to do with hyperreality, but an infinite accumulation of simulacra, an overabundance of information".[51] More than two decades later, music writer and teacher T. Cole Rachel writing for Pitchfork in 2015 commented that "if you aren't a super fan—or even a fan at all—there's no escaping Madonna. She is everywhere".[260] In addition to having been perceived as "omnipresent" by different outlets and for different reasons, other sources felt that beyond music industry she is one of the most "recognizable names in the world".[72][261][231]

Many different kinds of people[,] appreciate Madonna for many different reasons. Madonna has zealous fans who are young and old, straight and gay, educated and unschooled, First and Third World, black, white, brown, and yellow, and of every sexual preference, demografic category, and lifestyle imaginable. People who differ from one another in every way can all still find something relevant in Madonna's multidimensional, multimediated public imagery.

Relationship with critics and the press