The manor of Hillersdon was a historic manor in the parish of Cullompton, Devon, England which was held by the de Hillersdon family from the 13th century until the early 16th century. It was then held by a number of different families including the Cockeram, Cruwys and Grant families. Hillersdon House was built in the nineteenth century by the Grant family and is still in use.

History

Placename

The name probably means Hildhere's hill; dun means hill in Old English.[1] The name Hild is first found in the 7th century and the hill referred to may be the tumulus in Hillersdon Wood.[2]

Odo FitzGamelin

In the time of Edward the Confessor, the manor was held by Sheerwold and the Domesday Book of 1086 lists the manor of HILESDONE as the 18th of the 24 Devonshire holdings of Odo FitzGamelin, one of the Devon Domesday Book tenants-in-chief of King William the Conqueror. He was the son-in-law of Theobald FitzBerner, another of the Devon Domesday Book tenants-in-chief. The lands of both men later formed part of the feudal barony of Great Torrington.[3] His tenant at Hillersdon was Reginald.[4] In the Book of Fees (13th century) it is listed as held from the feudal barony of Great Torrington.[5]

de Hillersdon

In 1166 Hillersdon was held by Daniel de Brailega from William de Toriton.[7] The estate was the seat of the de Hillersdon family from the thirteenth century.[8][9] As was common, they had taken their surname from their seat. For a time the manor was held in two parts - East and West Hillerson. In 1241 Roger de Hele and William de Hilderesdon were the tenants, and in 1303 Roger de Hele and Roger de Hillesldon are returned as the tenants, while in 1346 Roger de Hillerysdon had both East and West Hillersdon.[7]

In 1456-57 Andrew Hillersdon (d1476) was Sheriff of Devon.[10] According to the Heraldic Visitations of Devon Andrew Hillersdon (son and heir of Robert Hillersdon (d.1499)), married Anne Edgecombe, "daughter and heir of Sir Richard Edgecombe of Edgecombe" and widow of Sir William Trevanion of Caerhays.[6][10] The Edgcumbe pedigree in the Heraldic Visitations of Devon however lists no "Sir Richard Edgecombe of Edgecombe" who left female heiresses at this date, and the estate of Edgcumbe in the parish of Milton Abbot remained in the Edgcumbe family until at least 1725.[11]) His son Roger Hillersdon, married into the prominent Fortescue family.[6][10]

Following these favourable marriages, the Hillersdon's sold the manor and moved elsewhere in the early 16th-century. Pole states "beinge advanced by their matches in diverse howses they left their dwellinge heere & removed unto their other howses of better valewe & sold this land away".[12] The seat of Roger Hillersdon, was Membland in the parish of Holbeton, Devon, where his descendants remained for several generations.[13]

After the dissolution of the monasteries, the manors of Cullompton and Upton Weaver were granted to Sir George St. Leger. His son Sir John St. Leger sold them to Thomas Risdon and it was then held by the Hillersdons.[14] Later the manor of Cullompton (or a share of it) seems to have belonged to the owners of the Hillersdon estate along with that of Ponsford (another manor in the parish of Cullompton).[15][16]

Cockeram

In the early seventeenth century, Risdon states that Hillersdon was the seat of "Mr Cockrane", whose father and grandfather had also held it.[18][19]

The Cockeram family descended from George Cockeram (d.1577) of "Hunington" in Devon, one of the overseers of John Lane’s will. In 1573 he was identified as a merchant.[20] The son of George Cockeram (d.1577) was also called George and was the first to be styled "George Cockeram of Cullompton". He died in 1586. Therefore the Cockerams might have purchased the estate directly from the Hillersdons in the early sixteenth century.[19][21]

In Queen Elizabeth's reign George and John Cockram, merchant, (probably a brother or cousin of George) supplied arms and armour for the defence of the realm.[20] As well as being patrons of the church, the family were great benefactors of the church and George and Bathsheba, the children of David Cockeram each gave the church a communion cup. They also gave a market cross to the town and lands for its upkeep.[21] In 1620 the head of the family was Humprey Cockeram.[20]

Robert Cockeram (1554-1632) was the third son of George Cockeram (d.1586) and was a Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford. His monument survives in Cullompton Church.[17] After being released from his duties at Oxford he spent much of his time at his house in 10 acres or at Growen (a farm immediately to the east of Hillersdon). In his will he bequeathed to the young scholars of Cullompton Grammar School, his "Cooper's Dictionary", to be kept chained to a desk. He also left money for repairs to the church and almshouses.[20][21]

Prous

Pole (d.1635), records that Hillersdon was owned by "Mr Prous of Taunton", Somerset, whose eldest son resided there.[22][23] Pole, although a contemporary of Risdon, makes no mention of the Cockram tenure although he does state "The patrons of the church of Columpton are Willm Every, Esquier, & Henry Cokeram, of Columpton".[24] It is possible that the estate was sold by the Cockerams to the Prowses in the early 17th century, in which case there would be no conflict between the account of Risdon and that of Pole.[23]

The Prouse family was an old Devon gentry family, branches of which were seated at Gidleigh Castle; Chagford; Barnstaple; Tiverton and Exeter. They descended from the marriage of Peter Prouz of "Eastervale" to Mary de Redvers. She was the daughter and heiress of William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon (d.1217) of Tiverton Castle, and widow of Sir Robert de Courtenay (d.1242) feudal baron of Okehampton.[25]

The ownership of Hillersdon in the rest of the seventeenth and early 18th century is unclear.[26]

Cruwys

In 1739, Joanna Burridge, widow of Samuel Burridge of Tiverton, and her daughter Elizabeth sold Hilersdon to Henry Cruwys of New Inn, Middlesex for £3,750.[27]

During his ownership of the estate he planted a number of oak trees in rows, both English Oaks and Turkey Oaks of a variety known as Iron Oaks which were possibly from the nursery of William Lucombe. Fifty years later, in 1796, a description of the trees and some seedlings were sent to Lord Dartmouth.[28]

Henry Cruwys died in 1760 and was buried at Butterleigh, near to Hillersdon and his wife Jane died five years later. He left his estate to his nephew Thomas Augustus Cruwys, Thomas Putt of Combe and Reverend Samuel Newte of Tidcombe, Tiverton. On Benjamin Donn's 1765 map of Devon, the house is shown as being in the ownership of 'Cruwys Esq'.[27]

Colman

Shortly before 1810 Hillersdon was listed by Rev. John Swete (d.1821) as the seat of Francis Colman (d.1820),[29] who was also lord of the manor of Cullompton.[30] He was the son and heir of William Colman of Gornhay in Devon and his mother was Jane Seymour, a sister of Edward Seymour, 8th Duke of Somerset (1701–1757), of Berry Pomeroy in Devon.[31]

Francis Colman was one of the beneficiaries of Thomas Augustus Cruwys' estate and he purchased the estate in 1771. In 1793 Richard Polwhele wrote that he had apparently built a new house at Hillersdon.[32] Colman married a Jemima Searle[32] and died in 1820, leaving three daughters and co-heiresses, the eldest of whom married into the Collins and then the Shiell families; the second married into the Pettiward family of Finborough Hall in Suffolk and the youngest Laura-Anne Colman married Thomas-Joseph Trafford of Trafford Park in Lancashire.[31]

Sweet

David Sweet, formerly of Gittisham, Devon, purchased Hillersdon and the manor of Cullompton from Francis Colman in 1802.[30][33] He died in 1807 without making a will and his wife Lucinda remarried. During this period Hillersdon House was let. On the death of her second husband in 1816, John Laxon Sweet (born 1795) inherited and he and his wife, Caroline Mackmurdo moved into Hillersdon.[34] As well as owning Hillersdon, John Laxon Sweet was also Lord of the Manor of Cullompton. By the 1820s, no courts were held, but the lord still had some manorial rights including appointing the town crier.[14]

Almost as soon as he inherited Hillersdon, John Laxon began to get into debt and by the early 1820s, parts of the estate were mortgaged for thousands of pounds. By 1825, the estate was auctioned although he retained the mansion and its grounds. Eventually, despite financial support from family and friends, he was forced to sell the property. By the time of the tithe survey in 1842, the estate was owned by Thomas Baker and the mansion was occupied by Daniel Roberts.[35]

Grant

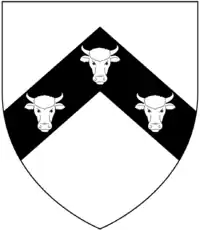

William Charles Grant (1817-1877)

The estate was purchased in about 1847 by William Charles Grant (1817–77), a Lieutenant of the First (Kings) Dragoon Guards. He was a nephew of Sir William Grant (1752-1832), Member of Parliament, Solicitor General and Master of the Rolls,[36] who had retired to Barton House, Dawlish, Devon.[37] William Charles Grant was lord of the manor of Cullompton.[36] He was descended from a younger son of Alexander Grant of Hillochhead in Scotland, a branch of Grant of Elchies.[36]

In 1843 Grant married Maria May (d.1891), a grand-daughter of Joseph May of Membland in Devon and of Hale Park in Hampshire.[37] She was a noted pteridologist,[38] and an adept of the "Victorian Fern Cult",.[39] At the Royal Horticultural Society's Exhibition of British Ferns held in London in August 1892, her son provided "Mrs Maria Grant's Memorial Prize for 10 varieties of Athyrium filix-femina", Silver Gilt Flora Medal, in her honour.[39]

William Charles Grant also built the present Hillersdon House to replace the earlier house which was in a dilapidated state,[40] and which had been offered for rent in the early 19th century.[41]

William John Alexander Grant (1851-1935)

Hillersdon passed to his second and eldest surviving son "Johnny"[42][43][44] William John Alexander Grant (1851-1935), JP,[36] the distinguished Arctic photographer who in 1895 married Enid Maud Forster, a daughter of William Forster (1818-1882), Premier of New South Wales, Australia, whom he divorced in 1901.[36][45] In the 1890s Hillersdon became known for its wild parties. One incident occurred after the Exeter Ball, when four young gentlemen plunged into one of the lakes, and were subsequently washed off in baths of Champagne. Elinor Glyn, a noted society beauty was part of the house party on this occasion.[46]

He died in 1935 and his funeral in the town of Cullompton was attended by hundreds of local people. The funeral procession was led by the Devon County Constabulary with one hundred members of the Cullompton Constitutional Club following behind. William Grant had planned his funeral in great detail and even prepared for it by sleeping in his coffin.[47]

Sturgis

After the death of William Grant in 1935 the house was inherited under his will by Sir Mark Beresford Russell Sturgis (1884–1949), KCB, Assistant Under-Secretary for Ireland, who took the additional surname of Grant, as a condition of the will. In the Second World War it housed US Officers and then became a bed and breakfast and later was divided into five flats.[48]

Glynn

It was purchased in 1982 by David and Gale Glynn, who having undertaken some refurbishment work sold it in 2009 for an asking price of £3 to 4 million.[49]

Lloyd

.jpg.webp)

In 2010 Hillersdon was purchased by International business man Michael Lloyd and has since undergone a complete refurbishment and is now used as a wedding venue.[50]

References

- ↑ Mawer, A.; Stenton, F.M. (1932). The Place-names of Devon. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 561.

- ↑ Colvin and Moggridge, section 1.1

- ↑ Thorn and Thorn, part 2 (Notes), Chapters 36 & 42

- ↑ Thorn and Thorn, Chapter 42:18

- ↑ Thorn and Thorn, Part 2 (notes), 42:18

- 1 2 3 Vivian, p.469

- 1 2 Reichel, OJ (1911). "Est Hillerdon". Devon and Cornwall Notes and Queries. 6: 22. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ Pole, pp.187, 308

- ↑ Colvin & Moggridge, 2011, section 1.3

- 1 2 3 Colvin & Moggridge, 2011, section 1.4

- ↑ Vivian, pp.324-5, pedigree of Edgcumbe

- ↑ Pole, p.308

- ↑ Colvin & Moggridge, 2011, section 1.5

- 1 2 Lysons, Daniel; Lysons, Samuel (1822). Magna Britannia: Volume 6, Devonshire. London: T Cadell and W Davies. p. 127. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ Foster, Murray T. (1910). "A Short History of Cullompton". Transactions of the Devonshire Association. 62: 159. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ Colvin & Moggridge, 2011, section 1.8-1.9

- 1 2 Vivian, p.205-6, pedigree of Cockeram

- ↑ Risdon, p.87

- 1 2 Colvin and Mogridge, section 1.6

- 1 2 3 4 Considine, John (12 October 2010). "3. Henry Cockeram: The Social World of a Seventeenth-Century Lexicographer". In Considine, John (ed.). Adventuring in Dictionaries: New Studies in the History of Lexicography. pp. 23–44. ISBN 9781443826266.

- 1 2 3 Hertford, Henry (1936). "A Cullompton Worthy". Devon and Cornwall Notes and Queries. 19: 132–6.

- ↑ Pole, p.187

- 1 2 Colvin and Moggridge, section 1.7

- ↑ Pole p. 188

- ↑ Vivian, p.626, pedigree of Prouse

- ↑ Colvin & Mogride, Section 1.8

- 1 2 Colvin & Mogride, Section 2.1

- ↑ Gray, Todd, William Luccombe and the Iron Oaks of Hillersden in 1796, Devon Documents (ed. T. Gray). Tiverton: Devon & Cornwall Notes & Queries, Special Issue (1996) pp. 88–90.

- ↑ Swete, John, Names of the Noblemen and Principal Gentlemen in the County of Devon, their Seats and Parishes at the Commencement of the Nineteenth Century, 1810, published in Risdon, 1811, p.4

- 1 2 Risdon, p.372, 1810 Additions

- 1 2 Burke, John (1838). "Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry; Or, Commoners of etc". London. p. 247 and footnote re Trafford family. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- 1 2 Colvin and Moggridge, sections 2.3 - 2.4

- ↑ Colvin and Moggridge, section 2.5

- ↑ Colvin and Moggridge, section 3.1

- ↑ Colvin and Moggridge, sections 3.2 - 3.5

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry, 15th Edition, ed. Pirie-Gordon, H., London, 1937, pp.954-5, pedigree of "grant of Hillersdon House"

- 1 2 Colvin & Moggridge, section 4.1

- ↑ Colvin & Moggridge, Section 4.2

- 1 2 Boyd, Peter D. A. "The Victorian Fern Cult in South-West Britain". Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ Mitchell, J.C. (1851). Eight views of Cullompton and neighbourhood together with a concise compilation of explanatory particulars and description. Cullompton: I. Frost.

- ↑ "Hillersdon House". Exeter Flying Post. 8 November 1821. Retrieved 13 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Leigh Smith Expeditions on board the Eira 1880, 1881-82". Freeze Frame. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ Wood, Janet. "Arctic Exploration: North West Pasage: The Pandora Voyage of 1876". World Through The Lens. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ "William Grant". The Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ Colvin & Moggridge, section 4.2

- ↑ Tyzack, Anna (5 June 2009). "Hillersdon House in Devon: a decadent affair - Telegraph". London: telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ Leonard, Jane; Barber, Chips (1994). Cullompton Past and Present. Exeter: Obelisk publications. ISBN 0946651949.

- ↑ "History". Hillersdon House. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ↑ Daily Telegraph newspaper on-line 5 Jun 2009

- ↑ "The House". Hillersdon House. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

Sources

- Colin and Moggridge (2011). Hillersdon House, Appendix 4, Archival Review of Landscape History. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- Pole, Sir William (1791). Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.). Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon. London. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Risdon, Tristram (1811). Rees; et al. (eds.). The Chorographical Description or Survey of the County of Devon (updated ed.). Plymouth: Rees and Curtis.

- Thorn, Frank; Thorn, Caroline, eds. (1985). Doomsday Book, Devon (in 2 parts). Chichester: Phillimore.

- Vivian, J.L. (1895). The Visitations of the County of Devon, 1531, 1564 and 1620. With additions. Part 1. Salt Lake city, Utah: Genealogical Society of the Church Of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. pp. 1–436. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Vivian, J.L. (1895). The Visitations of the County of Devon, 1531, 1564 and 1620. With additions. Part 2. pp. 437–899. Retrieved 6 November 2016.