Marion True (born November 5, 1948) was the former curator of antiquities for the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California. True was indicted on April 1, 2005, by an Italian court, on criminal charges accusing her of participating in a conspiracy that laundered stolen artifacts through private collections and creating a fake paper trail; the Greeks later followed suit.[1] The trial brought to light many questions about museum administration, repatriation, and ethics.

Early years

True was born in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, in 1948, and grew up in Newburyport, Massachusetts, where she developed an interest in Greek Antiquities.[1] True later received a scholarship to study the classics and fine arts at New York University, NYU. True also has a master's degree in classical archaeology from NYU's Institute of Fine Arts, and a PhD from Harvard, where she studied under Emily Dickinson Vermeule.[2][3] True was trained by Cornelius Clarkson Vermeule III, contemporary scholar of Ancient Art and Curator of Classical Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from 1957 to 1996.

In 1982, True joined The Getty as a curatorial assistant and later became a curator in 1986. True created a new policy for The Getty in 1987,[1] which required the museum to notify governments when objects were being considered for acquisitions. Under this new policy, if a government could prove an object had been illegally exported, the museum would return it.

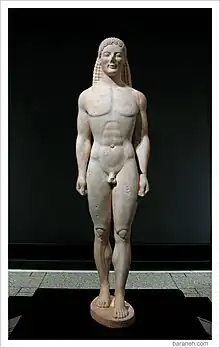

In 1992, True organized a symposium to debate the authenticity of a Greek kouros, which is referred to today as the Getty kouros.[1] The label in the museum reads, "Greek, 530 BCE or Modern Forgery". This Kouros was worth $10 million in 1985 when it was acquired, and it is believed to have been looted from southern Italy.

In 1995, True put in place another acquisition policy that prohibited the museum from acquiring antiquities that lacked thorough documentation, or that had not previously been part of an established collection.[1] Later in 1995, The Getty incorporated the collection of Barbara and Lawrence Fleischman into the museum's collection.[1] During that same year, True obtained a private loan to purchase a vacation home on the Greek Island of Paros; Larry Fleischman offered to loan True the money to repay this loan in 1996.[1] Later, lawyers would question if True and the Fleischmans had a conflict of interest.

Trial

In 2005, True was indicted by the Italian government, along with renowned American antiquities dealer, Robert E. Hecht, for conspiracy to traffic in illicit antiquities. She was accused of participating in a conspiracy that laundered stolen objects through private collection in order to create a fake paper trail that would serve as the items' provenance.[4] The Getty issued statements supporting True, "We Trust that this trial will result in her exoneration and end further damage to the personal and professional reputation of Dr. True."[1] The primary evidence in the case came from the 1995 raid of a Geneva, Switzerland warehouse, which contained a fortune in stolen artifacts. Italian art dealer, Giacomo Medici, was eventually arrested in 1997; his operation was thought to be "one of the largest and most sophisticated antiquities networks in the world, responsible for illegally digging up and spiriting away thousands of top-drawer pieces and passing them on to the most elite end of the international art market".[5] Medici was sentenced in 2004, by a court in Rome, to ten years in prison and a fine of 10 million euros, "the largest penalty ever meted out for antiquities crime in Italy".[5]

On October 1, 2005, True resigned from The Getty.[1] In November 2006, The Greek prosecution followed the Italian's lead, charging True with trafficking in looted antiquities due to her involvement in The Getty's purchase of an illicitly excavated golden funerary wreath.[1] On November 20, 2006, the Director of the museum, Michael Brand, announced that 26 disputed pieces were to be returned to Italy.

In a letter to the J. Paul Getty Trust on December 18, 2006, True stated that she was being made to "carry the burden" for practices which were known, approved, and condoned by The Getty's board of directors.[6] True testified for the first time in March 2007.

In September 2007, Italy dropped the civil charges against True.[1] The Getty also announced its plan to return 40 out of 46 objects. On September 26, 2007, Getty Center signed a contract with the Italian Culture ministry in Rome to return stolen arts from Italy.[7] Forty ancient art works would be returned including: the 5th century BC Aphrodite limestone and marble statue, in 2010; fresco paintings stolen from Pompeii; marble and bronze sculptures; and Greek vases.

In November 2007, the Greek criminal charges against True were dropped as the statute of limitations had expired. The wreath and three other items from the Getty's collection were returned to Greece.[1]

Criminal charges

All charges against True were eventually dismissed. Because the statute of limitations had expired, she was acquitted in 2007 of charges relating to the acquisition of a 2,500-year-old funerary wreath, which was shown to have been looted from northern Greece.[8] The wreath in question had already been returned to Greece. In 2010, an Italian court dismissed the remainder of the charges against her, holding that the statute of limitations has expired.[9]

Contested artifacts

Aphrodite of Morgantina was an acrolithic sculpture acquired by The Getty in 1988, it is a 7-foot-tall, 1,300-pound statue of limestone and marble.[10] The Museum and True ignored the obvious signs that it was looted. It was returned to Morgantina in early March, 2011.[11] It is thought that the sculpture actually portrays Persephone or Demeter, rather than Aphrodite.

The Getty kouros is an over-life-size statue in the form of a late archaic Greek kouros.[12] The dolomitic marble sculpture was also bought by Jiří Frel in 1985 for $7 million and first exhibited there in October 1986. If genuine, it is one of only twelve complete kouroi still extant. If fake, it exhibits a high degree of technical and artistic sophistication by an as-yet unidentified forger. Its status remains undetermined: today the museum's label reads "Greek, about 530 B.C., or modern forgery".[12]

The Golden Wreath was bought by The Getty in 1994 for $1.15 million.[4] True was shown the wreath in a Swiss bank vault before purchasing and determined that it was "too dangerous" to purchase, because of its signs of looting. Under the advisement of The Getty's board, True purchased it through Christoph Leon, a Swiss art dealer.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Combs, Jacob, and Morag Kersel. "A True Controversy: The Trial of Marion True and Its Lessons for Curators, Museums Boards, and National Governments." : 1–15.

- ↑ Christopher Reynolds, "The puzzle of Marion True" Archived 2007-01-12 at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2005

- ↑ Suzanne Muchnic, "Getty curator Marion True, indicted over acquisitions, has often spoken on ethical issues" Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, May 27, 2005

- 1 2 3 Mead, Rebecca. "Onward and Upward with the Arts: Den of Antiquity." The New Yorker 9 April 1007:1–8

- 1 2 Men's Vogue, November/December 2006, Vol. 2, No. 3, p. 46.

- ↑ LATimes.com ~ "Getty lets her take fall, ex-curator says"

- ↑ BBC NEWS, Getty to hand back 'looted art'

- ↑ Intl. Herald Tribune "Ex-curator acquitted in case of Greek relic"

- ↑ Jason Felch, "Charges dismissed against ex-Getty curator Marion True by Italian judge (updated)" Los Angeles Times, October 13, 2010

- ↑ Flech, Jason, "The Getty Ship Aphrodite Statue to Sicily: The Iconic Statue, bought in 1988, is among 40 object of disputed origin repatriated." LA Times 23 March 2011

- ↑ Morreale, Giovanni, "Chasing Aphrodite: Venus of Morgantina", Times of Sicily February 16, 2012

- 1 2 [J. Paul Getty Museum. Statue of a kouros. Retrieved September 2, 2008.]